A Reader’s Guide to the Big Beautiful Bill: Part 5

How Republicans are changing Medicaid.

Happy Thursday! Today I’ll be sharing Part 5 of my series breaking down the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the recent Republican budget bill, from start to finish.

In case you missed them, here are the previous installments:

In these newsletters, I’m trying to a) walk you through what, exactly, the OBBBA will do, and b) help get you comfortable with reading a piece of legislation, by not just summarizing the bill — but actually walking you through the text itself.

I hope you’ve been finding them valuable! If you appreciate the time and research that goes into putting them together, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my ability to keep doing this kind of work:

And if you can’t upgrade, that’s OK! You can also help by clicking the heart button above to “like” the newsletter and by forwarding to your friends and family and encouraging them to subscribe.

So far, we’ve made our way through 6.5 of the OBBBA’s 10 titles. Title VII encompasses the two biggest parts of the package: changes to taxes and to Medicaid. We covered taxes in the last installment; today, we’ll walk through the rest of the title. (For the sake of time, we won’t touch on every provision, I promise.)

If you want to read along, here’s a link to Title VII. We’re starting with Subtitle B, on page 219.

Title VII: Finance (pp. 87-262), continued

We’ll need some context to understand this section. Let’s start by clearing something up: Medicare provides health insurance to people 65 and older and some people with disabilities; Medicaid provides health insurance for low-income people.

Got it? OK, let’s make it more confusing.

When someone is covered by Medicare, the federal government will pay for much of their medical costs, but the recipient is still on the hook for certain payments. That’s why Medicare recipients will often supplement their coverage with private insurance or a Medicare Advantage plan.

Then, you have another category of people: those who are on Medicare, with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to afford a private plan to pay for what Medicare does not.

That’s where Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs) come in, as a way to help people who don’t qualify for full Medicaid pay the out-of-pocket costs of Medicare. It’s sort of like the mid-point between the two programs: a supplement to Medicare, administered through Medicaid. (Not confusing at all, right?) The program is sometimes known as “partial Medicaid.”

The process for signing up for an MSP involves a lot of hurdles; as of 2017, half of the Americans who were eligible for the program weren’t signed up for it. The Biden administration enacted a rule in 2023 aimed at making it easier to enroll for MSPs, reducing the documentation requirements and streamlining the process.

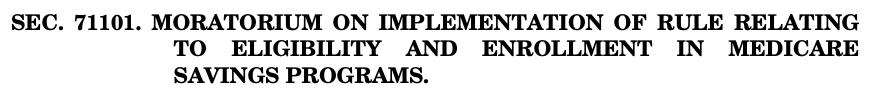

Now you have enough context to understand this section, the first one in Title VII, Subtitle B of the OBBBA:

As you can see, the OBBBA places a moratorium on implementing the Biden-era rule on MSPs until September 2034.

This change hasn’t gotten very much coverage, although it will impact the likelihood that low-income seniors will be able to pay for their health care costs. One of the few outlets that covered it, The Bulwark, did so with this headline: “Yes, They’re Going After Medicare Too.” I think that title is a bit simplistic (the article itself is more nuanced). Medicare Savings Programs aren’t Medicare benefits; they’re a separate program that helps people pay for the costs Medicare benefits don’t cover. This provision also doesn’t cut MSPs themselves, just a recent change that would have made it easier to sign up for one.

But you can decide for yourself whether you think this counts as “going after” Medicare. That’s the whole point of this series! I’m trying to give you the tools to understand what this consequential piece of legislation says. You can decide how to think about it!

This is another case of the OBBBA imposing a moratorium against implementing a Biden-era regulation through September 30, 2024.

Similar to the above section, the regulation being paused here would have simplified the process for enrolling in Medicaid, including by prohibiting states from requiring seniors or disabled people from having to come in for in-person interviews to determine eligibility.

Medicaid is jointly administered by the federal and state governments, which means there are 50 different Medicaid programs, all run according to different rules and regulations.

Such a fractured system creates some vulnerabilities: for example, people are sometimes able to (illegally) claim Medicaid benefits in two states at once. A 2022 audit by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) found that, in the month of August 2020 alone, more than 327,000 people fraudulently received $117 million in Medicaid payments from multiple states.

If you’re reading the OBBBA along with me, you’ll see that this is the first of several sections that amend Section 1902 of the Social Security Act, codified here, which lists out 87 requirements for state Medicaid plans.

This section adds an 88th, requiring each state to participate in a system that will be set up by the HHS Secretary for states to share the addresses and Social Security numbers of their Medicaid recipients in a unified database, in order to ensure that no one on the list is double-dipping.

A 2023 audit by the HHS found that, in the 14 states that were examined, $249 million in Medicaid payments fraudulently went to enrollees who had died. Oops!

So here’s requirement #89!

Starting in 2027, every quarter, states will have to review the Death Master File (great band name!) kept by the Social Security Administration to ensure that no one enrolled in Medicaid in their state has died without their knowledge. Any deceased enrollees will be disenrolled.

If you keep reading, there’s also this, which seems to anticipate the possibility of this review making mistakes…

Starting in October 2026, no one will be eligible for Medicaid who isn’t:

Immigrants here illegally are already not eligible for Medicaid, but other groups here legally under other authorities than the above (like those who have refugee, asylum, or parole status) are currently eligible for Medicaid and no longer will be.

Immigrants who have “been battered or subjected to extreme cruelty in the United States by a spouse or a parent” — no matter their legal status — are also currently eligible for Medicaid. They no longer will be under the OBBBA.

Medicaid does reimburse hospitals for emergency care provided to any immigrant, here legally or illegally, who would qualify for Medicaid if not for their immigration status, which will continue under the OBBBA.

Another nine-year moratorium on implementing a Biden regulation.

This one is a 2024 rule setting minimum staffing standards for Medicare- and Medicaid-certified long-term care facilities, which had already been struck down by a district court.

The meat of this section is right here:

Under current law, when someone enrolls in Medicaid, the government will retroactively cover their medical costs for the previous three months. Now that will be the last one month for Medicaid enrollees who qualify under the Obamacare-era expansion of the program, and the last two months for traditional Medicaid recipients.

This section prevents Medicaid funds from being used towards any group that…

The words “Planned Parenthood” aren’t mentioned anywhere there, but they are the only tax-exempt organization “primarily engaged in family planning, in family planning services, reproductive health, and related medical care” that “provides for abortions” other than for rape, incest, and the life of the mother and receives more than $800,000 annually from Medicaid.

Notably, federal money is already prohibited from funding abortions other than for rape, incest, and the life of the mother, dating back to a 1976 law known as the Hyde Amendment. But, in some states, Medicaid funds can be used for beneficiaries to receive other services from Planned Parenthood, including contraception, pregnancy tests, and cervical cancer screenings. Federal funding will no longer be able to be used for Planned Parenthood to provide those services under the OBBBA, although the provision has been temporarily blocked in court.

These “community engagement requirements” — generally referred to as “work requirements” — are the biggest change the OBBBA will make to Medicaid.

Currently, no such requirements apply to Medicaid recipients. Under the OBBBA, starting in 2027, most Medicaid recipients older than 19 and younger than 65 will have to meet one of these requirements each month:

Anyone is exempt…

Recipients will be required to verify their compliance at least every six months; if they fail to do so, they will receive notice from their state and have 30 days to make a “satisfactory showing” of compliance. If they still do not show compliance, they will be removed from Medicaid.

States will be allowed to set up provisions to offer waivers to individuals who experience “a short-term hardship event during a month.” States will also be allowed to apply for waivers to not start imposing work requirements until 2029, which will be at the discretion of the HHS Secretary.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, roughly 10 million Americans are projected to become uninsured due to the OBBBA, many of them because of the work requirements in this section (not necessarily because they do not comply with the requirements, but often because of the paperwork hurdles involved in proving that they do).

This is the only provision in the OBBBA that really impacts Medicare directly. It will limit Medicare benefits to anyone who is…

That means, just like for Medicaid, a number of immigrants who currently qualify for Medicare because they have refugee, asylum, or parole status, or because they suffered from spousal or parental abuse, will lose their access to benefits. Under this section, the loss of benefits will kick in for members of these groups in 18 months.

Just like for Medicaid and Medicare, this section prohibits Obamacare premium tax credits from going to anyone other than citizens, permanent residents, Cuban and Haitian entrants, and individuals residing here under the Compact of Free Association.

The main point of Medicaid is to provide health insurance to low-income people. But because Medicaid payments go directly from the government to hospitals (to subsidize beneficiaries’ treatments), the program ends up keeping afloat a substantial number of hospitals that serve areas with mostly poor residents. Without Medicaid money, many hospitals are expected to suffer.

In particular, the National Rural Health Association estimates that the changes to Medicaid outlined above would lead to almost $70 billion less money coming into rural hospitals, which will lead to some closing. This is why the final section of Subtitle B introduces something called the “Rural Health Transformation Program,” a new fund that will be distributed to rural hospitals to make up for the lost revenue from individuals who won’t be using their services after losing Medicaid coverage.

The OBBBA appropriates $10 million to the fund every year until 2030.

Have you ever wondered what it looks like when Congress increases the debt limit? Well, here goes:

You’ll notice it doesn’t actually say how high the debt limit is now. Let’s find out together. We’ll start with Public Law 118-5, better known as the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) of 2023, which was the last legislative vehicle to raise the debt ceiling:

Basically, the FRA — a bipartisan deal during the Biden era — didn’t set a hard number for the debt limit either. It just suspended the limit until January 1, 2025; after that, the law said, the new limit would just be the amount of debt the U.S. had accumulated up to that point. That number was $36.1 trillion. Hence, the new debt limit is $41.1 trillion.

How long will it take to reach that point? Probably only about two and a half years. See you then!

Some federal programs, like Social Security, are available to all Americans, even the very wealthy. Others, like the Child Tax Credit, start to phase out after a certain income level.

Unemployment insurance (UI) benefits — which are made available to Americans after they lose their job — have historically been in the first category. The OBBBA moves it over to the second:

According to the IRS, in 2022, almost 15,000 millionaires collected $213.3 million in unemployment benefits. Not anymore. Anyone who loses a $1 million job will no longer be eligible for UI benefits under the OBBBA.

Thank you Gabe for this series. It is truly invaluable and not available anywhere else that I am aware of !!

An eye-opener to me that millionaires could receive unemployment compensation. Glad that was struck.