A Reader’s Guide to the Big Beautiful Bill: Part 3

A tour through the GOP megabill’s impact on energy policy.

Good morning, everyone! I’m back with my third installment of my ongoing series walking you through every provision in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the Republican budget bill that was signed into law earlier this month.

Click here for Part 1 and here for Part 2.

We all know that the OBBBA contained big changes to taxes, health care programs, and more. But the package also included a lot of important changes to energy policy, which will be our focus today as we make our way through the parts of the bill written by the Energy and Natural Resources (ENR) and Environment and Public Works (EPW) Committees.

These reader’s guides take a lot of time and research to put together. If you find them helpful, it’s always appreciated if you drop a like by clicking the heart button above, share the newsletter with your friends and family, or consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber.

Thank you for your support! Now, let’s get reading…

Title V: Energy and Natural Resources (pp. 66-83)

Here’s a link to this title, so you can read along at home!

In order for oil and gas companies to engage in drilling on federal lands (“onshore drilling”) or waters (“offshore drilling”), they have to purchase leases from the federal government. The OBBBA seeks to expand both types of drilling.

First, onshore drilling. The Interior Department is required by federal law to hold onshore lease sales every quarter in each state “where eligible lands are available.” But lease sales have frequently lagged behind that timeline, particularly during the Biden administration, which went years without holding such sales, arguing that they had discretion to deem all lands in the U.S. as ineligible.

The OBBBA directs the Interior Secretary to “immediately resume quarterly onshore oil and gas lease sales,” and clarifies that “eligible lands” means all public lands where drilling isn’t legally prohibited, in order to avoid pauses by future administrations. At a minimum, the new law requires four oil and gas lease sales a year in nine states: Alaska, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Utah, and Wyoming.

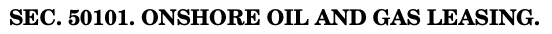

This section also sends us on a bit of a legislative scavenger hunt. This is from page 66:

OK, let’s head to Public Law 117-69, better known as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022.1 Here’s the relevant provision:

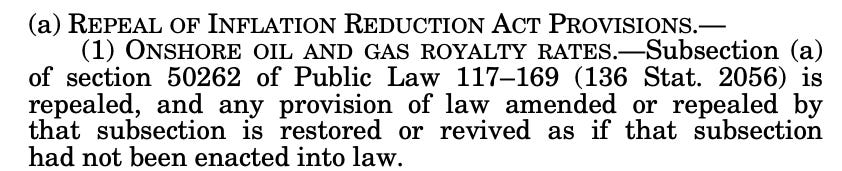

OK, we’re gonna need one more stop!2 Here’s the text the IRA was amending:

Now we can understand what’s going on. Back in 1920, the Mineral Leasing Act required companies to pay a 12.5 percent royalty on any proceeds from oil and gas produced from federal land. In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act increased the royalty to 16⅔ percent. So, now, we see that the OBBBA repeals the Biden-era change and brings the royalty amount back down to 12.5 percent, what it was from 1920 to 2022.

Good work, legislative detectives! Mystery solved.

Finally, this section of the OBBBA also repeals another provision in the IRA that ended a practice known as noncompetitive leasing. Under this practice, if an auction for an oil or gas lease on federal land failed to yield any offers, the auction would end, and the land would become available to the first company that asked for it, which would only have to pay as little as $1.50 per acre. (Roughly 99% of these lands would then never see oil and gas production, bringing no revenue back to the government.) Under the IRA, if an auction failed, the land would remain in federal hands until a future auction. Under the OBBBA, the first-come, first-served system will be brought back.

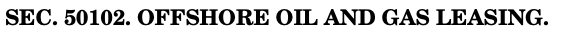

OK, let’s venture offshore. The federal government also controls oil and gas drilling right off the coast of the U.S., an area known as the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). The OCS is split into four regions:

This section of the OBBBA requires the Interior Secretary to hold at least six additional lease sales in the Alaska region (across the next seven years) and 30 in the “Gulf of America region” (across the next 15 years). Yes, this is the first use of the term “Gulf of America” in U.S. law.

Here’s an interesting provision related to the Alaska sales:

When Alaska became a state, the law that admitted it into the union promised that 90% of royalties for oil and gas leases in the state would be paid to the state government. (One legislator recently called this “Alaska’s birthright.”) But future laws have created carve-outs, so that royalties are split 50/50 between the state and federal government for many Alaska leases (the same ratio that other states usually get). The House version of the OBBBA would have mandated a return to the 90/10 split for OCS sales in the Alaska region; the final version doesn’t go quite that far, but does still increase the current 50/50 ratio to 70/30.

Speaking of royalties, the IRA also raised the amount of royalties companies had to pay the government for offshore gas leases to 16⅔ percent, just like for onshore leases. We’re going back to 12.5 percent here too.

Another IRA repeal. This section cancels a provision from the 2022 law that imposed a royalty on “on all gas produced” from a federal oil/gas lease site, including methane “consumed or lost by venting, flaring, or negligent releases.”

After decades of debate, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) — a 19 million-acre expanse in Alaska — was opened to drilling by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017. This section would call for four more ANWR oil and gas lease sales in the next 10 years, following the two held under the TCJA (though both received few or no bidders).

The royalties from the four new sales will be split 50/50 between the Alaska and federal governments through 2033. But starting in 2034, Alaska’s royalties will go up to 70/30.

Alaska is also home to the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska (NPRA). At 23 million acres, it is the largest area of public land in the country, approximately the size of Indiana.

The OBBBA would require six oil gas lease sales there over the next ten years, with the same royalty sharing as above (50/50 until 2033, then 70/30 after that).

This section directs the Interior Secretary to quickly move ahead in the next 90 days with coal leasing on federal lands, which had largely been paused under Biden.

This will drop the royalty for coal produced from federal leases — currently set at 12.5 percent — to 7 percent.

Little self-referential there!

As you may recall from Part 1, “An act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of H.Con.Res.14” (or AATPFRPTT2OHCR14, as I like to call it) is the official name of the OBBBA.

In addition to quickly approving pending applications for coal leasing (from two sections ago), the Interior Secretary is also required in the next 90 days to make at least four million new acres of public land available for coal leasing.

There are currently only coal leases on about 405,000 acres of public land, so this would be a major increase. The OBBBA does make clear that, when looking for federal lands to meet the 4 million quota, no land that qualifies as one of these can be included:

Under this section, if a company needs to mine coal on a federal land in order to make it economically viable to mine on a nearby state or private land, and approval has already been given to mine coal on the federal land in the past, no new approval is needed for the new project.

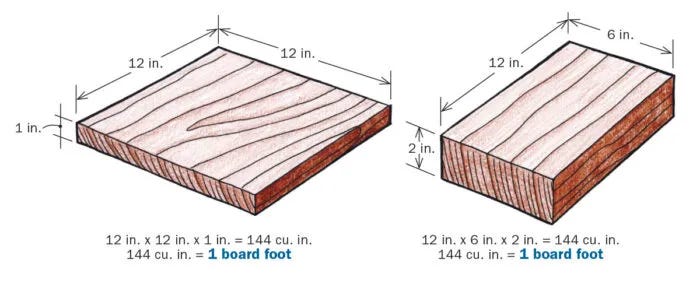

Now, time for some logging. This section directs the Interior Secretary, every year between Fiscal Years3 2026 and 2034, to sell 250 million more board-feet of timber from National Forest land than the year before. This would increase logging on federal lands by about 25% over the coming years.

A board foot, by the way, is a unit of measurement for lumber that equals 144 cubic inches. (So, for example, a piece of wood that is one foot long, one foot wide, and one inch thick would be one board foot.)

So far, we’ve mostly dealt with making it easier and less expensive for oil, gas, and coal companies to drill and mine on federal land. But the OBBBA also makes it more expensive for renewable energy projects to take place on federal land.

Specifically, this section doubles a fee levied on wind projects on federal land and increases a separate fee on wind and solar projects.

Under this section, the above fees (and any other revenue from renewable energy projects on federal land) will be split 25/25/50 between the state, county, and federal governments.

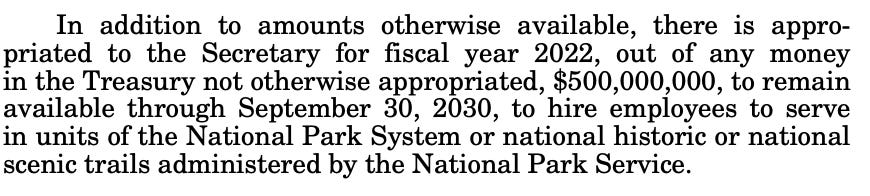

This section rescinds4 three pots of IRA money, two that dealt with conservation and one that funded the hiring of new National Park Service employees.

Here’s the IRA language concerning that last pot of money, which is now being clawed back:

America is nearing its semiquincentennial, otherwise known as its 250th birthday. During his 2024 campaign, Trump promised to throw “the most spectacular birthday party” for the country, including a “Great American State Fair” with pavilions from all 50 states.

This section of the OBBBA appropriates $150 million for unspecified “events, celebrations, and activities surrounding the observance and commemoration” of America’s 250th anniversary.

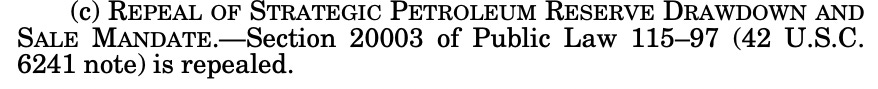

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) is the U.S.’ emergency stockpile of oil, stored in huge underground salt caverns in Texas and Louisiana.

The Biden administration sold off almost half the stockpile to stem the increase in fuel prices after the Russia/Ukraine war, leaving the SPR at its lowest level since the 1980s. (It currently has about 395 million barrels of oil.) As a result, this section would appropriate $171 million to purchase more oil for the reserve and $218 million for maintenance of the SPR storage facilities (the Biden-era drawdown resulted in structural damage to the aging salt caverns).

Here’s another provision in this section:

Public Law 115-97 is the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017: this is one of the few times you’ll see the OBBBA (the signature legislation of Trump 2.0) repealing something from the TCJA (the signature legislation of Trump 1.0). But the provision in question called for seven million barrels of oil from the SPR to be sold in 2026 and 2027, which is no longer as appealing of a policy now that the SPR is at such low levels.

This is more pots of IRA money being rescinded, including grants to facilitate interstate electricity transmission lines, grants to train contractors in the installation of home electrification projects, and a program providing loan guarantees to Native American tribes for energy-related projects

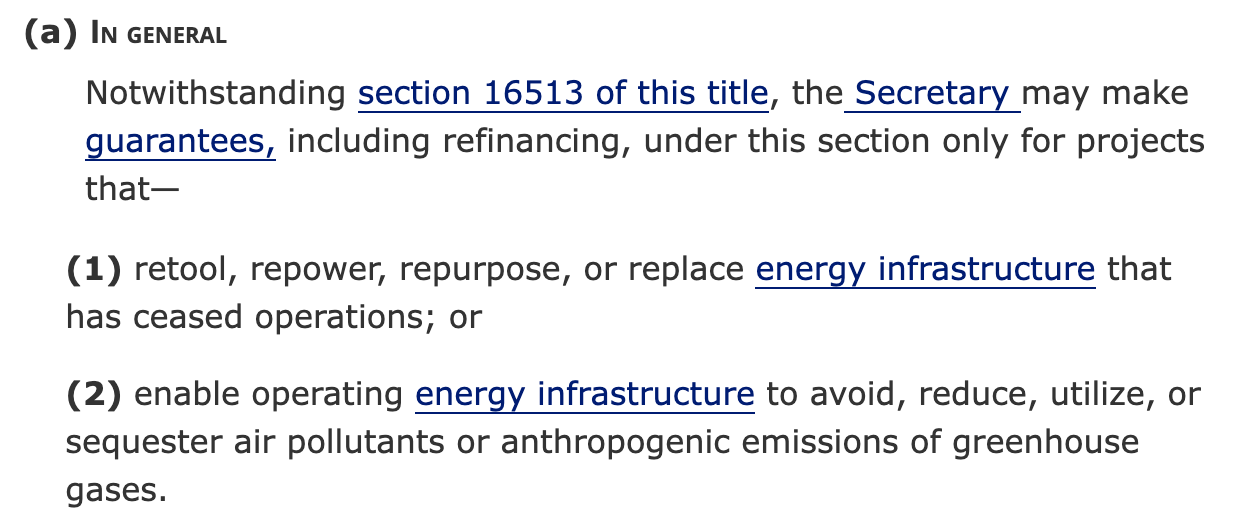

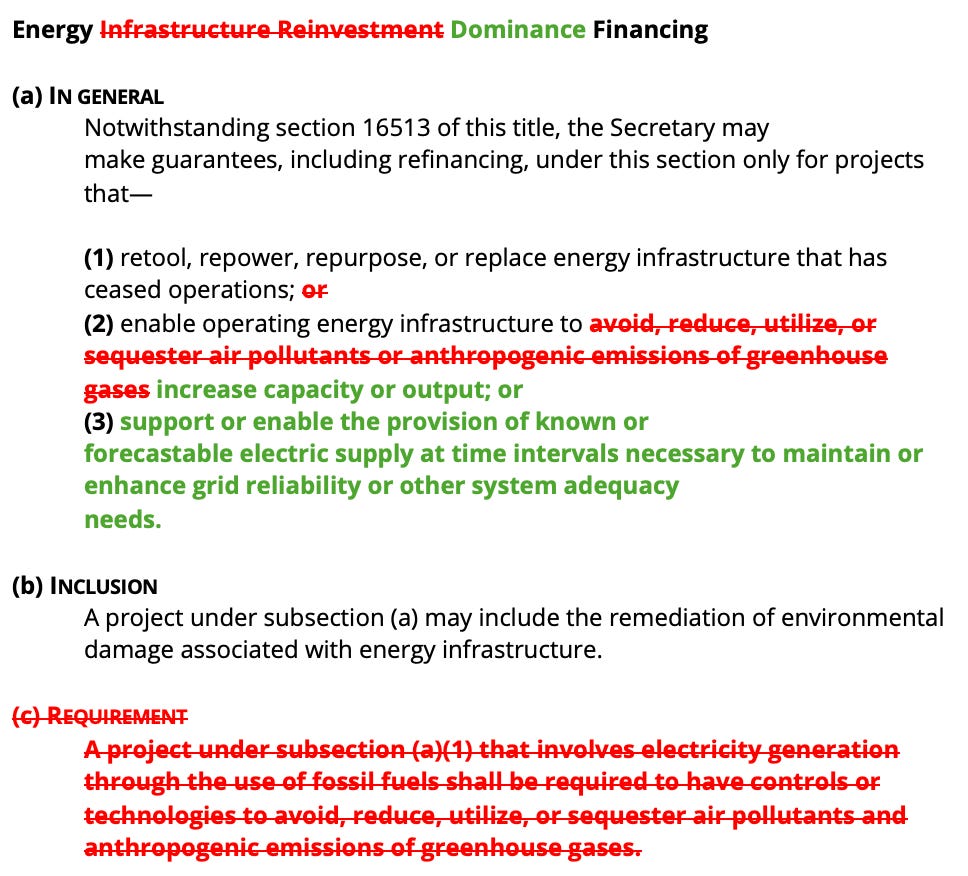

The IRA created something called the Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Loan Program, which was set up to guarantee loans to projects that retool, repower, repurpose, or replace certain types of energy infrastructure.

In a clever act of legislative artistry, the OBBBA would quietly retool the retooling program. Let’s start with the text as the IRA left it:

But the OBBBA instructs us to lop off everything after “to” in paragraph (2) and replace it with “increase capacity or output.” Suddenly, without ever mentioning greenhouse gas emissions one way or another, the OBBBA has taken a program that was partially intended to reduce emissions and given it a new goal that will have the effect of increasing them.

Here’s a closer look at how the program’s description will evolve under the new law. (The OBBBA also renames it, adds a third category of projects, and removes another climate-related requirement.)

The section appropriates $1 billion for the fund through 2028.

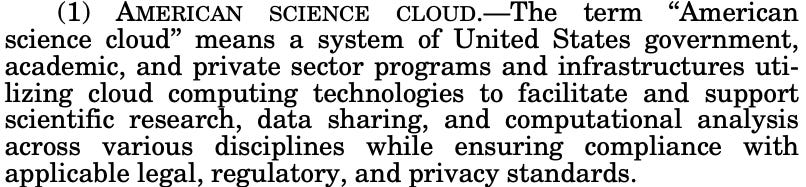

This section appropriates $150 million for a project that will work to clean up Energy Department data to make it “suitable for use in artificial intelligence and machine learning models” and then “initiate seed efforts for self-improving artificial intelligence models for science and engineering” powered by that data.

Specifically, the OBBBA says that the data should be used to develop more energy-efficient “next-generation microelectronics,” essentially trying to use AI to create technologies that will lower energy consumption. The resulting models will be made available to the entire “American science cloud,” the OBBBA says.

If you’re wondering what the “American science cloud” is, here’s the OBBBA’s definition:

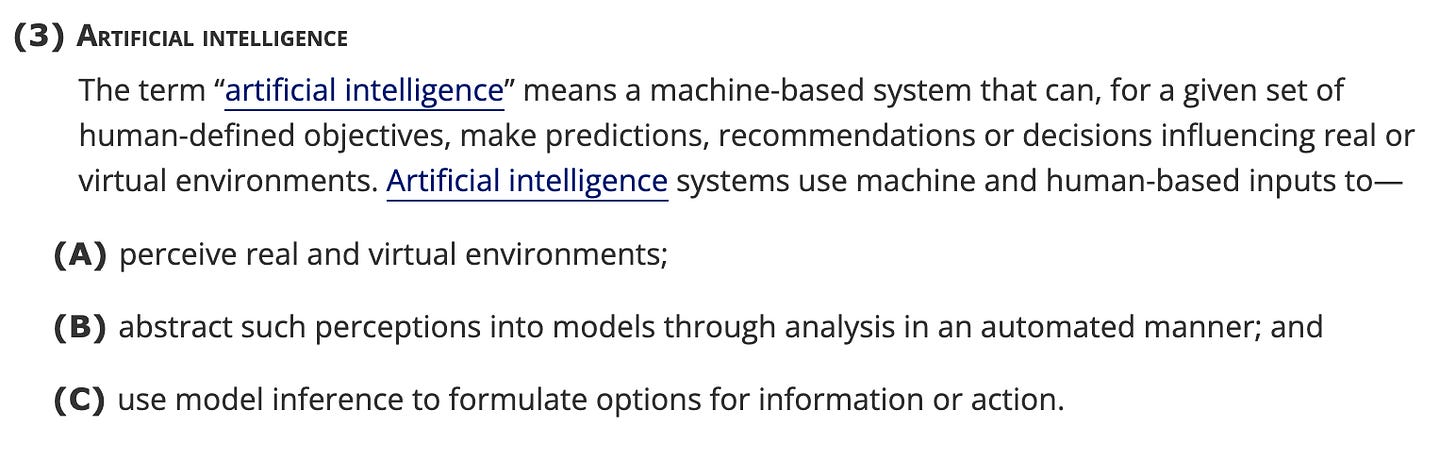

While we’re at it, how does the U.S. government define AI? The OBBBA points us to the definition found in 15 U.S.C. 9401(3), language adopted in 2020:

This section appropriates $1 billion over the next 10 years for construction projects that will “restore or increase the capacity or use of” water conveyance facilities (like canals and pipelines) or surface water storage facilities (like reservoirs and dams).

Title VI: Environment and Public Works (pp. 83-87)

Here’s your specialized link to Title VI, so you can read along with me. This title has 26 sections, but we’re going to take the first 24 all at once, because they all do the same things: rescind money for climate projects from the IRA.

One notable rescission here is the end of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), which included the “Green Bank” program to finance clean energy projects. That’s the program that EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin had called a “gold bar” scheme and already moved to terminate, sparking a legal battle.

Other rescissions include the end of grant programs to replace gas vehicles with electric vehicles, reduce air pollution in schools, and promote “environmental justice” initiatives.

Now we’ll tackle the last two sections of the title.

You wouldn’t necessarily expect increased arts funding in a Republican funding bill… but don’t forget that President Trump has taken an interest in the Kennedy Center, naming himself chairman and pledging to renovate a building that he’s said is in “tremendous disrepair.”

The OBBBA would appropriate more than $256 million towards that goal.

Last section for the day! There has been a lot of discussion lately — from the left and the right — about how long it can take infrastructure projects to wind through the federal permitting process, which is primarily governed by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1970.

This section will create a new structure under which project sponsors can access expedited timelines for their environmental reviews under NEPA, as long as they pay a fee that will equal 125 percent of the costs of preparing the review. Any project that pays that fee will be guaranteed to have their Environmental Assessment completed within six months and their Environmental Impact Statement done within a year.

Environmental Assessments currently take an average of almost 10 months to complete, while Environmental Impact Statements take an average of 2.2 years.

Fun Reader’s Guide Tip #1: Laws are numbered according to which Congress they were passed in, and which number law they were within that Congress. So, the IRA is Public Law 117-69 (or P.L. 117-69) because it was the 69th law passed in the 117th Congress. The OBBBA is P.L. 119-21, the 21st law of the 119th Congress.

Fun Reader’s Guide Tip #2: If the OBBBA is changing a previous law, it will usually tell you the previous law and the U.S. Code citation it is changing. Here, for example it says, “Section 17 of the Mineral Leasing Act (30 U.S.C. 226) is amended…”

If you want to see what’s being changed, for the most part, it’ll be easiest to go straight to the cited section of the U.S. Code (which will always have a “U.S.C.” in it). The U.S. Code is a compilation of every law ever passed, put together by the congressional Office of the Law Revision Counsel. So, if a law was passed in, say, 2010 and then part of it was taken out in 2012 and then another part was amended in 2014 and then another part was added in 2016, the U.S. Code will be the most up-to-date version of the law encompassing all those changes.

If you go there, you’ll be sure to get the actual text that the OBBBA is changing. If you go to the cited law (here, the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920), you won’t know if other laws since then have made relevant changes that would only be captured in the U.S. Code.

Here, 30 U.S.C. 226 refers to Section 226 of Title 30 of the U.S. Code. The code has 53 titles, organized by category. Title 30 is “Mineral Lands and Mining.” Section 226 is “Lease of oil and gas lands.”

Fun Reader’s Guide Tip #3: In the federal government, Fiscal Years run from October 1 to September 30. So Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 began on October 1, 2024 and runs through September 30, 2025. FY 2026 will start on October 1, 2025 and run through September 30, 2026. And so on.

Fun Reader’s Guide Tip #4: When a bill “rescinds” funds — not unlike the recent rescissions package — it means that any unspent funds left in the specified account will be clawed back and returned to the general Treasury.

Gabe, these summaries are superb. Clear, concise, easy to read, and understandable explanations. Just fantastic work. More than worth whatever it is I’m paying each month for a subscription. But I’m also happy to keep paying that amount and not more!!!

Your facts and analysis are just right for me to absorb without eyes glazing over! Thank you.