A Reader’s Guide to the Big Beautiful Bill: Part 4

We’ve arrived at the heart of the bill.

Good morning, everyone! It’s time for Part 4 of my ongoing series diving deep into the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the recent Republican budget legislation.

For those just joining us: in Part 1, we covered the defense and agriculture provisions of the package; in Part 2, we covered banking, science and transportation; and in Part 3, we covered energy and the environment.

Together, we’ve made it through 80+ pages of legislation. Congratulations!

Now, we’ve arrived at the biggest portion of the bill: Title VII, the part written by the Senate Finance Committee. Per Senate Rule XXV(i), the Finance panel has jurisdiction over “revenue measures” and “health programs financed by a specific tax or trust fund,” which means this title contains the two biggest parts of the OBBBA: its changes to taxes and to Medicaid.

At 175 pages, it is by far the longest of the bill’s ten titles. In order to avoid overwhelming you with too much information, I’m only going to focus on tax provisions today and, unlike in previous installments, I won’t touch on every section of the title (there are more than 100, including a slew of corporate tax rules that won’t be relevant to very many of you). My goal with this edition is still to take the same granular look at the OBBBA, but just confined to the provisions in the title that I think a) are the most broadly applicable to people who are reading this or b) tell us something interesting about the package and how it was crafted.

As always, this primer will be designed so you can read it while paging through the OBBBA yourself, in order to feel more comfortable reading a piece of legislation, an important skill for any citizen. If you want to try your hand at it, here’s a link to Title VII. I’ll also be quoting frequently from the text, so if you’re just here to learn about the details of the bill (also a worthy civic goal!), feel free to just scroll on.

Sure, this title can be dry at times. But it’s also the one that applies to all of us, as long as you pay taxes in America, so it’s worth having a handle on. And there are plenty of quirky provisions thrown in, which can make it an interesting (dare I say even entertaining) read. You know never what sort of tax perks you’ll stumble on.

Got your coffee? In a comfy chair? OK, let’s venture together into the heart of H.R. 1, the title that puts “big” in the One Big Beautiful Bill.

Title VII: Finance (pp. 87-262)

We’ll start out simple. The United States has seven tax brackets, based on income. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), the signature legislation of President Trump’s first term, lowered the tax rate for all but the lowest and second-highest of these brackets, a change that was set to expire at the end of 2025.

Here’s the text in the OBBBA (p. 87) that makes those tax cuts permanent1:

In case you want to see how this impacts you, here are the current income thresholds for each tax bracket, plus their tax rates before the TCJA (which would have returned in 2026 without this bill) and their post-TCJA tax rates, which are now permanent under the OBBBA:

That’s pretty straightforward. But the tax code is thousands and thousands of pages. Now, let’s make things more complicated.

To arrive at your taxable income, you take your gross income (how much money you made) and potentially a few initial deductions (known as above-the-line deductions) to derive your adjusted gross income (AGI). Then, from there, there are other deductions one can take to arrive at your taxable income.

The tax code is littered with tons of different deductions that may or may not apply to you. You can choose between wading through all of these itemized deductions or simply taking the standard deduction, a fixed amount that you can lop off your AGI to get your taxable income. The vast majority of taxpayers take the standard deduction; a lot of the provisions in today’s newsletter will deal with changes to various itemized deductions that you can only access if you choose not to standardize.

The TCJA nearly doubled the standard deduction, a change that was poised to sunset at the end of this year. The OBBBA sets it even higher ($15,750 for single filers and $31,500 for joint filers, up from the TCJA’s $15,000 and $30,000) and makes that a permanent floor. It will increase with inflation.

Before the TCJA, there was something called the personal exemption, which was a fixed amount that all taxpayers under a certain income level could deduct from their tax bills, no matter if they standardized or itemized. This was originally intended to make sure Americans would have a baseline level of tax-free income they could live off of; as of 2017, the personal exemption was $4,050.

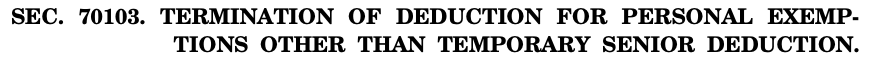

The TCJA temporarily eliminated the personal exemption, with the logic that the doubling of the standard deduction would take its place. The OBBBA makes this elimination permanent.

With one exception.

You may have heard President Trump claim that the OBBBA ends taxes on Social Security benefits. The Social Security Administration even told beneficiaries that in a controversial email. But it isn’t strictly true. Loyal readers will remember that the OBBBA was passed under the reconciliation process, which is governed by the pesky Byrd Rule. Well, one of the requirements of the Byrd Rule is that a reconciliation bill can’t touch Social Security.

So the GOP used this provision to get around that: they resurrected the personal exemption, but only for seniors, as a stand-in for ending taxes on Social Security benefits.

Read it for yourself:

The provision essentially creates a $6,000 tax break for anyone over 65, although the deduction scales down for those whose incomes exceed $75,000. The hope is that this will largely cancel out any tax burden from Social Security benefits — but the overlap isn’t 1:1.

There are some people on Social Security who won’t be able to take advantage of the new deduction (those who start accepting benefits before age 65; those who receive because of disability, not age), and there are others who will receive the new deduction but don’t receive Social Security benefits (those who don’t start accepting benefits until age 67).

Importantly, this special perk sunsets in 2028.

The Child Tax Credit (CTC) is exactly what it sounds like: a tax credit for parents with children. The TCJA increased the CTC from $1,000 per child under 17 to $2,000, ending in 2025. The OBBA will push the CTC up to $2,200 and make that permanent.

Before 2017, there was a class of deductions called miscellaneous itemized deductions that taxpayers could take, for a random group of things including investment expenses, legal fees, and unreimbursed employee expenses.

The TCJA temporarily ended these deductions, and the OBBBA makes that permanent. But there’s one type of unreimbursed employee expenses that the OBBBA makes an exception for:

Teachers who pay for classroom supplies out-of-pocket are already eligible for a $300 above-the-line deduction. But now, if they itemize, they will be allowed to deduct the full amount of the supplies they pay for. Educators who teach kindergarten through 12th grade for at least 900 hours during a school year are eligible for this deduction; as you can see, the OBBBA also adds coaches to the list of eligibility.

OK, let’s see what we have here.

If we venture over to Title 26, Section 132(f) of U.S. Code, we see that this provision is amending a list of benefits that companies can give employees tax-free. Under the law, if employers give any of these to their workers, the employers can deduct it as a business expense and the workers don’t have to count it as income on their taxes:

The TCJA suspended this practice, but the OBBBA will bring it back. Except, as we saw, it will strike subparagraph (D), which means anyone who is reimbursed by their company for biking to work each day (a benefit created by Congress in 2009) can no longer write it off their taxes. Sorry, bikers.

This provision has not been popular in the gambling community. Here it is in full:

Previously, gamblers had been allowed to deduct 100% of their losses from their tax bill.

So, let’s say someone won $1,000 in gambling one year and lost $400. They would deduct the losses from their income, and pay taxes on their $600 profit.

Under this provision of the OBBBA, that same person would only be able to deduct 90% of their $400 loss, or $360, from their taxes. So, they would have to pay a tax bill amounting to $640 of income (their $1,000 winnings minus $360), even though they only made $600 from gambling. They now have to pay taxes on $40 of “ghost income” they never made.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that this one small change will net the federal government $1.1 billion over 10 years, an attempt to partially offset the cost of the tax cuts elsewhere in the bill. However, professional gamblers (for whom the difference could really be in the millions) say this underrates the fact that fewer people will gamble now that they have to pay taxes on their losses, which means lower incomes and reduced revenue for the government.

Nevada’s senators, worried about the impact on the Las Vegas economy, have already introduced a bill to try to roll back this change, which has picked up some bipartisan support.

A lot of controversy here! The state and local tax deduction, better known as the SALT deduction, allows taxpayers who itemize to deduct the amount they paid in state taxes from their federal tax bill. The TCJA put a cap on it, though, making it so taxpayers could only write off up to $10,000 under this deduction.

This was not popular among Republican lawmakers in high-tax states like New York and California, who have constituents paying well above that in state taxes. (In fact, nobody remembers now, but 12 House Republicans voted against the TCJA for this reason, including now-ardent Trump ally Elise Stefanik!)

These Republicans made a big push to raise the SALT cap in the OBBBA. Did they succeed? Well, here you go:

The $10,000 cap has been stricken, replaced with a $40,000 cap.

Here we get to several consecutive sections that are based on President Trump’s 2024 campaign promises. Don’t believe me? Here’s what the heading on page 99 calls them:

The title of this section (“No Tax On Tips”) sounds very definitive. But let’s take a look at the fine print:

OK, so really it’s “No Tax On Tips Up To $25,000, Which Starts to Phase Out For Incomes Over $150,000.”

Let’s keep reading and see if we learn anything more.

Oh, what’s that?

Make that “No Tax On Tips Up To $25,000, Which Starts to Phase Out Out For Incomes Over $150,000, But Only Until 2028.” Not really a great bumper sticker.

One more thing, because I’ve seen some misinformation about this. This provision does say that the deduction is only available for “cash tips,” which I’ve seen lead to some suggestions that tips using credit cards won’t count.

But let’s read for ourselves!

The legal definition of “cash tips,” under the OBBBA, includes tips that are “charged.”

This was another presidential promise, ending taxes on overtime pay. As above, there are a few catches: it only applies to overtime pay up to $12,500; it phases out for those making more than $150,000; and it ends when Trump’s term does.

Another campaign pledge fulfilled, allowing Americans to deduct interest payments on car loans from their tax bills. The cap here is $10,000. Note to car buyers: are the vehicles that will be eligible. Have to be made in the USA!

Like the other Trump tax breaks, this one will end in 2029 and is available to itemizers and non-itemizers alike.

This is an interesting one, creating a new tax-advantaged investment account called a Trump account that parents of any child under eight years old will be able to open starting in 2026. Parents will be able to contribute $5,000 to the account each year; it will then be made available to the child starting at age 18.

(Note that the original draft of the OBBBA called these “Money Accounts for Growth and Advancement,” or MAGA Accounts. The final version dispenses with these formalities, simply naming it after the president.)

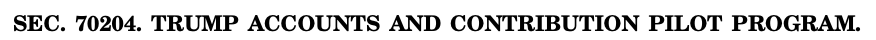

One other interesting note here:

For children born between 2025 and 2028, the federal government will contribute $1,000 in each Trump account, a pilot program that is somewhat similar to “baby bonus” ideas that have been floating around on both sides of the aisle for years.

Does your office provide free snacks or even meals to you at work? Before 2017, companies that did so could write off those costs from their taxes. The TCJA lowered this deduction and set it to completely sunset at the end of this year.

The OBBBA doesn’t bring the deduction back, but — oh! — what’s that? An exception?

Who will be the lucky few that still get to deduct office snacks from their tax bills? Self-employed Substack journalists, I hope? Let’s keep reading:

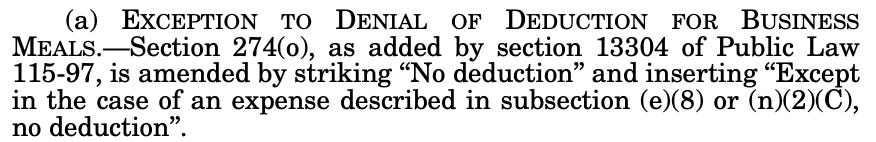

Nope, only meals for employees on fishing vessels will remain tax deductible. And, fish processing facilities north of the 50-degree latitude line.

Where in the U.S. is above 50 degrees latitude?

It’s almost as Lisa Murkowski, the senator from Alaska, was the key vote for the OBBBA.

If I move Wake Up To Politics headquarters to an Alaskan fish processing facility, you’ll know why.

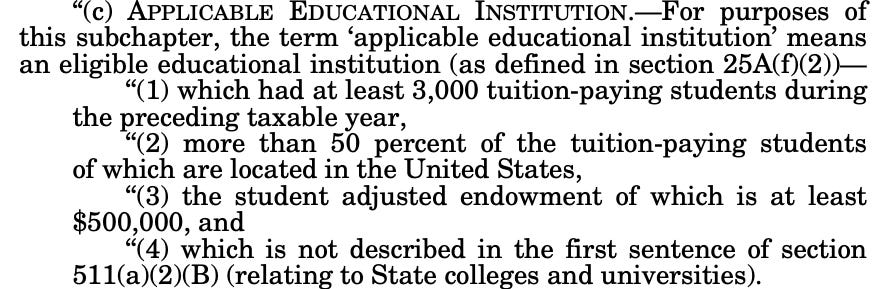

This section imposes a tax on the endowments of universities that meet this criteria:

Per the New York Times, there are about 50 colleges that fit this bill, from Harvard and MIT to schools like Berry College in Georgia and DePauw University in Indiana. Currently, these institutions pay a 1.4% tax on their endowments; that will go up to as high as 8% under the OBBBA (a significant increase, obviously, but still not nearly as much as the maximum 21% tax rate proposed in the initial draft).

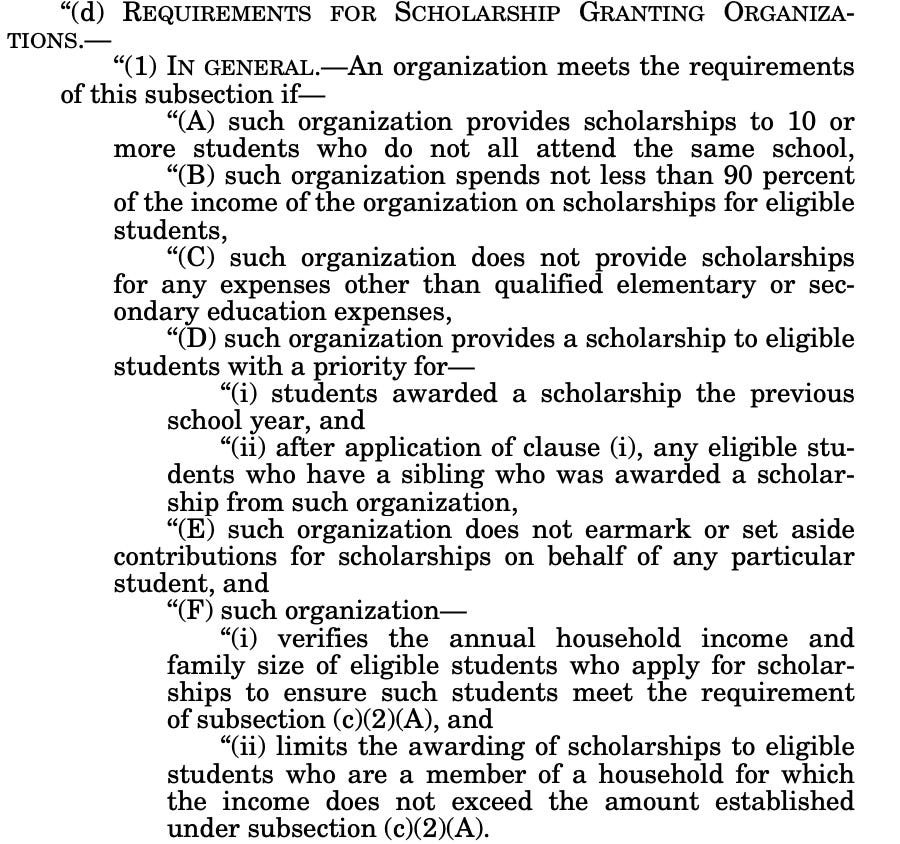

Reconciliation bills can only touch tax and spending law, but there are all sorts of ways to make policy change through the tax code. For example, this section doesn’t sound very consequential from the title, but it is actually the first national school voucher plan in U.S. history, though it’s structured through private donations.

Here’s how it would work.

American taxpayers will be able to donate up to $1,700 to certain organizations and then get 100% of that money back as a tax credit:

Here are the organizations that can receive the donations:

Those organizations will then be able to turn those donations into scholarships for “eligible students” (those whose families earn up to 300% of their area’s median income)…

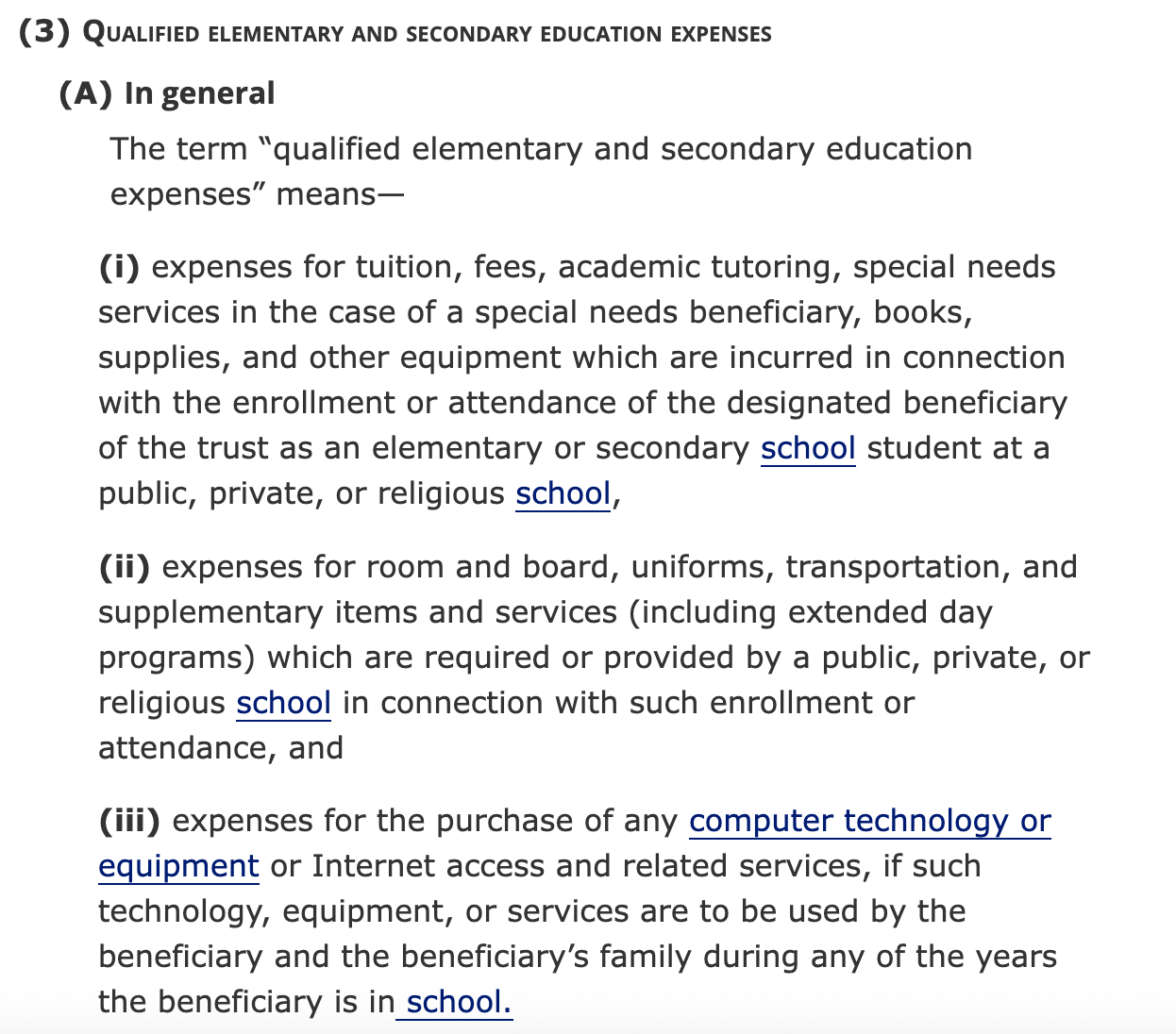

…who will then be able to use that money for “qualified elementary or secondary education expenses”:

A quick trip over to Title 26, Section 530(b)(3)(A) tells us that these expenses include tuition, fees, room and board, uniforms, and other costs usually (but not exclusively!) associated with private school.

So, essentially, you’ll have the government reimbursing private citizens, who will donate to organizations, who will offer scholarships to some students, which they can then use to pay for private school (and maybe for certain expenses attached to attending public school, too — it’s not clear).

Notably, states will get to choose whether to participate; if they do, it will be their job to vet the scholarship organizations that meet the criteria.

Good news for charities! The vast majority of taxpayers who take the standard deduction will still be able to write off some amount of charitable giving, through a new above-the-line deduction for donations up to $1,000.

The National Council of Nonprofits estimates that this provision will generate $74 billion for nonprofits over the next decade.

Bad news for charities! Starting in 2026, taxpayers who itemize will only start qualifying for the charitable tax deduction if they contribute at least 0.5% of their adjusted gross income to charity.

The National Council of Nonprofits estimates that this provision (along with an accompanying provision that sets a similar 1% floor for corporations) could reduce charitable giving by $81 billion.

“The bill gives and the bill takes away,” one expert on charitable giving explained.

This deduction will quintuple, from $10,000 to $50,000! She strikes again.

Fun fact: this is the first time the words “Green New Deal” will have been mentioned in a U.S. law, since no such proposal has ever passed during a Democratic administration — although it is the name President Trump has given to the environmental policies of the Biden era.

As such, this is the group of sections that repeal most of the clean energy tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022.

Republicans who support the tax credits were able to argue for some to remain longer than others, so you’ll see varying phase-out times.

The electric vehicle tax credit, despite Elon Musk’s protests, will disappear in just two months:

A tax credit for home solar panels will last until the end of the year:

But a tax credit for other energy efficient home improvements, like heat pumps, will survive for another year:

Tax credits for wind and solar will continue through 2027:

A hydrogen production tax credit will remain until 2028:

The details vary, but the point is consistent: the tax benefits of adopting clean energy will mostly go away under the OBBBA.

We’ve made it to the final section of the tax subtitle! Direct File is a program created by the IRA that allows taxpayers to prepare and file their federal tax returns directly on the IRS website. It’s kind of like the government’s answer to TurboTax (which is why TurboTax was none too happy with the program).

It launched as a pilot program with 12 states in the 2024 tax year and broadened to 25 states in the 2025 tax year

An earlier draft of the OBBBA would have eliminated Direct File, but the final version doesn’t go that far. Instead, it appropriates $15 million for the Treasury Department to put together a report on potentially replacing Direct File with a public-private partnership.

Phew! We did it.

Nice job working through Title VII, Subtitle A of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. We’ll be back next time to break down how the package is changing Medicaid.

Have a great weekend!

Today, unless otherwise noted, when you see the OBBBA amending previous law, we’ll be dealing with Title 26 of U.S. Code, where the U.S. tax code is enshrined.

Wow. I see why Lisa Murkowski keeps winning elections!

Thank you for the addition of the personal asides. They make this much more digestible.