Trump vs. Every Member of Congress

The president could face a notable defeat on the House floor today.

Good morning! It’s Thursday, January 8, 2026. This morning, we’ll dive into a power that’s utilized so rarely that we don’t often have a reason to discuss it: the presidential veto. And not just that: a pair of vetoes — which could be overturned — that place President Trump on the opposite side of every member of Congress, including every Republican.

If you still have a question to submit for tomorrow’s Q&A issue, there’s still time to send one in here or by clicking “reply” to this email. Looking forward to seeing your questions!

You all know that I love finding under-the-radar pieces of legislation to tell you about: bills that might not cover the world’s most flashy topics, but that will help improve the lives of real people and that often pass with sweeping bipartisan support.

The writers Matthew Yglesias and Simon Bazelon have called these bills the work of “Secret Congress” (because of how productive lawmakers can be when nobody is watching), though I’ve argued they shouldn’t be a secret (because you deserve to know what your elected representatives are working on). To that end, I’ve covered all sorts of random bills in these pages: even one about shark attack notifications.

But even I have a limit. Every week, there are bills that advance through Congress that are so specific, and so noncontroversial, that I really can’t find an argument for telling you about them. The Finish the Arkansas Valley Conduit Act and the Miccosukee Reserved Area Amendments Act are two examples in this category.

We’ll get into what they do in a minute, but for now, just take my word for it that these pieces of legislation are as humdrum as bills passed by Congress get. They each sailed through both the House and Senate with completely unanimous support — not a single dissenter — before landing on President Trump’s desk on December 18. And then, on December 29, in that hazy period between Christmas and New Year’s when few people are paying attention to the news, Trump did something unusual: he vetoed them.

Today, the House will vote on whether to override Trump’s vetoes, something even more unusual still. We’ll take this story in two parts: why Trump vetoed these bills (the stated reason and the more likely reason), and what happens next (potentially, a rare defeat for the president on Capitol Hill).

I.

OK, now let’s dive into what these two pieces of legislation actually do.

The Finish the Arkansas Valley Conduit Act, as its name suggests, concerns the Arkansas Valley Conduit, an infrastructure project in Colorado with a long history. It was first authorized by Congress back in 1962, but was never built because local authorities didn’t have enough money to pay the construction costs. Then, in 2009, President Barack Obama signed a law creating a cost-sharing plan for the project (the federal government would pay for the project, but 35% of the cost would have to be repaid by the local government within 50 years). Ground was eventually broken in 2020.

When all is said and done, the plan is to build a 130-mile pipeline that will deliver clean, filtered drinking water from the Pueblo Reservoir to 39 communities and 50,000 people in southeast Colorado. (The communities currently rely on groundwater, and some have struggled with water contamination from naturally-occurring radioactive elements.) But the project keeps running out of money (even after receiving funding from the Biden-era infrastructure law); this bill offers Colorado authorities a helping hand by saying they have 100 years, not 50, to repay the federal government, and that the feds won’t charge them interest.

It sailed through the House and Senate. The project may be taking a long time, but no one wants to vote against clean drinking water.

Well, one person did. President Trump vetoed the measure, explaining that it would “continue the failed policies of the past by forcing Federal taxpayers to bear even more of the massive costs of a local water project — a local water project that, as initially conceived, was supposed to be paid for by the localities using it.”

“Enough is enough,” Trump’s veto message continued. “My Administration is committed to preventing American taxpayers from funding expensive and unreliable policies. Ending the massive cost of taxpayer handouts and restoring fiscal sanity is vital to economic growth and the fiscal health of the Nation.”

Those are all fair reasons to be skeptical about the project, but the way the White House handled this raised some eyebrows. Normally, when the president is going to veto something, the White House issues a formal veto threat (here’s an example); they said nothing ahead of time here. Also, the Congressional Budget Office has said that the bill will cost the federal government less than $500,000. If the veto was really about fiscal responsibility, why did Trump sign bills the same week that would spend $13 million on an Arizona energy project and $75 million on fisheries around the Great Lakes?

Two alternative explanations have been offered. First, Trump has already been feuding with the state of Colorado over its imprisonment of Tina Peters, a former county clerk who was convicted for giving an unauthorized individual access to voting machines as part of efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election. (Trump wrote recently that the governor of Colorado should “rot in Hell” for not pardoning Peters.) Many have speculated that Trump’s veto could have been an attempt to punish Colorado for the Peters situation, including a former chairman of the state Republican Party, who has said he finds it “almost impossible to not believe that this is nothing but an act of vengeance and vindictiveness on the part of the president toward Colorado.”

Second, the bill was sponsored by Rep. Lauren Boebert (R-CO), whose district would reap the benefits of the new water pipeline. Boebert is a Trump ally — but she was also one of the four Republicans, much to the president’s dismay, who signed the discharge petition that forced the release of the Epstein Files. (Recall that the White House went so far as to bring Boebert into the Situation Room in an attempt to get her to drop her name from the petition. She refused to budge.) Could the veto have been Trump’s revenge against Boebert?

Boebert seems to think so. She released a scorching statement after the veto — perhaps the harshest statement a congressional Republican has released about Trump since his re-election — in which she wrote, “I sincerely hope this veto has nothing to do with political retaliation for calling out corruption and demanding accountability. Americans deserve leadership that puts people over politics.” Here’s more from the statement, which is quite the read:

President Trump decided to veto a completely non-controversial, bipartisan bill that passed both the House and Senate unanimously. Why? Because nothing says “America First” like denying clean drinking water to 50,000 people in Southeast Colorado, many of whom enthusiastically voted for him all three elections.

I must have missed the rally where he stood in Colorado and promised to personally derail critical water infrastructure projects. My bad, I thought the campaign was about lowering costs and cutting red tape.

But hey, if the administration wants to make its legacy blocking projects that deliver water to rural Americans; that’s on them.

She, um, does not seem happy. (By the way: what would you have said if I told you in January 2025 that Marjorie Taylor Greene had broken with President Trump and Lauren Boebert would be releasing statements about him like that? Boebert, it should be noted, hasn’t renounced her support of Trump like her frenemy MTG has, but still: Trump has ditched allies for less bruising comments than Boebert’s in that statement.)

We’ll return to Boebert in a moment. For now, we should also touch on the Miccosukee Reserved Area Amendments Act, the other bill vetoed by the president.

This one concerns the Miccosukee tribe, a Native American tribe whose reservation includes part of Everglades National Park in Florida. There is a nearby part of the Everglades called the Osceola Camp; it’s not technically part of the Miccosukee’s reservation, but many members of the tribe have their homes there.

The Osceola Camp also experiences frequent floods. This bill would formally make the area part of the Miccosukee reservation, and give the tribe more control over the water infrastructure there, in an effort to prevent flooding. The bill also authorizes up to $14 million for the Interior Department to build structures that would protect the Osceola Camp from flooding, in consultation with the tribe.

Once again, the measure was championed by Republicans — including Rep. Carlos Gimenez (R-FL) and Sens. Rick Scott (R-FL) and Ashley Moody (R-FL) — and approved unanimously by both chambers.

Here, President Trump’s veto message does not dwell as much on fiscal responsibility, despite the bill being much more expensive than the Colorado measure — another reason to be skeptical of Trump’s explanation for the first bill. He does write that “it is not the Federal Government’s responsibility to pay to fix problems in an area that the Tribe has never been authorized to occupy,” but in this message, Trump doesn’t even try to hide the fact that the veto is primarily about politics, not the price tag.

You see, the Miccosukee tribe joined other groups this summer in suing to close “Alligator Alcatraz,” the federally-funded, Florida-run immigration detention facility that was built adjacent to their land. A federal district judge temporarily blocked the facility in response to the lawsuit, although an appeals court later paused that order.

Trump openly linked his veto of the anti-flooding measure to the Miccosukee lawsuit. “Despite seeking funding and special treatment from the Federal Government, the Miccosukee Tribe has actively sought to obstruct reasonable immigration policies that the American people decisively voted for when I was elected,” the president wrote. “My Administration is committed to preventing American taxpayers from funding projects for special interests, especially those that are unaligned with my Administration’s policy of removing violent criminal illegal aliens from the country.”

Trump managed to find controversy in two seemingly non-controversial bills, picking an implicit fight with every single member of Congress (since they all supported both measures) in the process. What happens now?

II.

To put our “Schoolhouse Rock” hats on for a moment: even when the president vetoes a piece of legislation, the bill still has one more chance to become a law, if two-thirds of both the House and Senate vote to override the veto.

This is very rare. Out of the 2,597 presidential vetoes in American history, only 111 — about 4.3% — have been overridden.

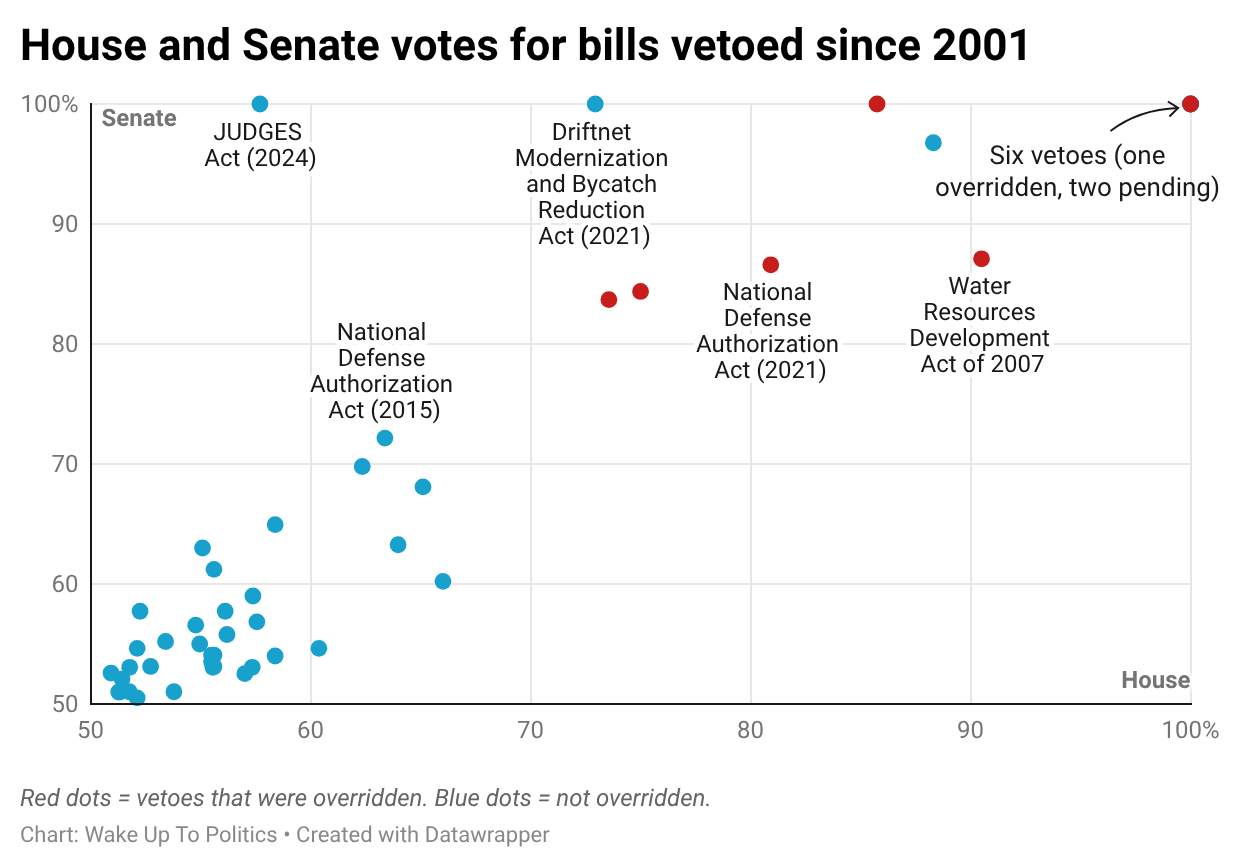

One reason for this is that presidents don’t normally veto bills as popular as the two that Trump vetoed last month. Below, I’ve charted every veto under the Trump, Biden, Obama, and George W. Bush presidencies, based on what percentage of the House and Senate voted for the bill before sending it to the president’s desk:

As you can see, most of the 48 bills in the chart land below the 60/60 range: they were supported by less than 60% of representatives and senators before being vetoed.

Six were 100/100s (supported unanimously by both chambers), including the two most recent vetoes by Trump. A few more lie above the 70/70 range, suggesting bicameral supermajority support. (Note that everything above the 66/66 range passed with “veto-proof” majorities, enough to override.)

Red dots in the chart above represent overridden vetoes. From looking at the chart, you can immediately see that Trump has entered the danger zone of presidential vetoes. Before now, there were 11 bills this century that presidents vetoed despite having passed with veto-proof support in Congress (the dots in the upper right section of the chart); six of those vetoes were overridden.

You might think that Republican congressional leaders could simply decline to hold a veto override vote, sparing Trump from the potential embarrassment of being rebuked by Congress. But, nope, that’s not an option: Article I, Section 7, Clause 2 of the Constitution says that the chamber that originated the bill “shall…proceed to reconsider” it after the president vetoes it, meaning lawmakers can’t just ignore a veto and move on.

The chamber can, by majority vote, opt not to hold a formal override vote, but it has to at least consider a potential override. No discharge petition needed here.

Interestingly, Republican leaders aren’t even trying to hold a vote to block an override vote on Trump’s two vetoes, perhaps a sign that they aren’t confident they’d win such a maneuver. Instead, the House will be voting today on whether to override each veto. (The Senate will then weigh in, but only if the House does vote to override. If the originating chamber votes not to override, the bill dies then and there without the other chamber getting a say.)

According to Politico and Axios, Republicans believe there may be enough votes today to override Trump’s vetoes in the House — which would mark a striking defeat for the president in a Congress that has generally followed his wishes. If both chambers buck Trump on these bills, they would be the first successful veto overrides in five years.

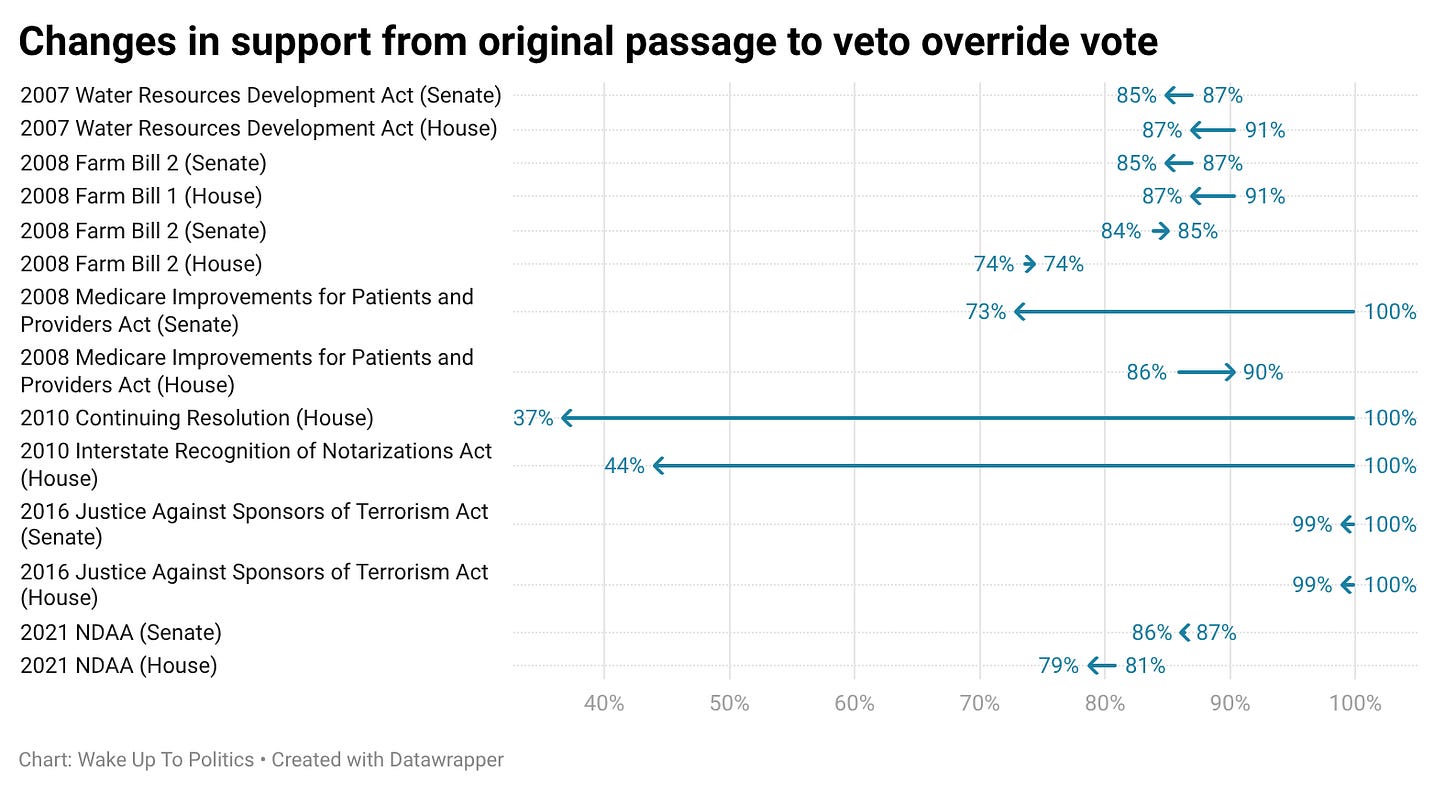

Republicans have good reason to worry that their members will break with Trump here. In this century, almost every time a veto-proof bill was vetoed and then an override vote was held, support for the bill barely budged between the original vote and the override vote:

The two exceptions prove the rule: a continuing resolution that was vetoed because it was moot by the time it reached the president, and a bill where new information about how it could impact foreclosures emerged between congressional passage and the veto.1 In this case, the two bills have neither become moot, nor has new information emerged (unless you count Trump’s opposition).

Available historical evidence would suggest Trump has a problem on his hands: when presidents veto bills that passed with such overwhelming support in Congress, it normally doesn’t go well for them.

It would be easy to view these as a pair of local stories, only concerning small sections of two states. But they’re more than that.

First, they’re national stories because if it’s true the president vetoed bills to deliver drinking water to Coloradans or prevent flooding in Florida for purely political reasons, that’s a big deal.

Second, if the vetoes are overridden, it would mark yet another small, but notable, crack in Trump’s relationship with congressional Republicans.

Trump often prefers to show congressional Republicans a stick, not a carrot. You want projects funded in your district? Then you better stay in line. Sign a discharge petition I don’t like, and — poof — there goes your precious project.

That approach can work, but it’s dangerous when you’re operating with as slim margins as he is. The sorts of projects that Trump snubbed in Colorado matter a lot to individual lawmakers (and they are often so unanimous because members want other members to vote for their pet projects in exchange. Many lawmakers won’t want to start going down the road of picking and choosing which local grants go through). After that statement from Lauren Boebert, if I were in the White House, I wouldn’t automatically count on Boebert’s vote the next time they need it. That might not be the wisest move when you only have enough cushion for one, maybe two, defections on key votes.

And there are a lot of key votes coming up, including votes in the Senate today on war powers and in the House on health care. (To tie everything together, note that two of Trump’s vetoes in his first term were on war powers resolutions. If a Venezuela war powers resolution passes, it is unlikely to be with a veto-proof majority. But if a Greenland war powers resolution comes up for a vote, it could be a different story.)

Trump is quick to punish congressional Republicans when they get out of line. Will that strategy scare Republicans into submission, or lead to Congress flexing its power back at him in subtle (and not-so-subtle) ways? Today’s veto override votes could give us a big hint.

These are two of the four vetoes this century of bills unanimously approved by both chambers of Congress. The others also took place during the Obama era: one was the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (which allowed families of 9/11 victims to sue the government of Saudi Arabia), which Obama vetoed in September 2016. (He said in his veto message that the bill would create “complications” in U.S. foreign policy, and potentially lead to other countries allowing their citizens to sue the U.S. government.) The veto was overridden.

The other was the Presidential Allowance Modernization Act (which would have limited the pensions and allowances of former presidents), which Obama vetoed in July 2016 — just months before he was to become a former president. (He said that it would “impose onerous and unreasonable burdens on the offices of former Presidents, including by requiring the General Services Administration to immediately terminate salaries and benefits of office employees and to remove furnishings and equipment from offices.”) The House opted not to hold an override vote; I have been unable to find a reason why.

Smart analysis and good example of why I always read Gabe's work in spite of occasional disagreements with tone and slant. These are fun and interesting times for astute observers like Gabe (and his readers)!

Thank you for this analysis. Just out of curiosity, is this a Trump veto or Miller veto? I just don’t think Trump has the interest, attention span, or intelligence to understand what he’s vetoing and he certainly didn’t write those justifications. Is this the kind of thing if he’s asked about it, he’ll say he doesn’t know or isn't familiar with it?