The Sandcastle Presidency

Trump is building almost nothing that will last long term.

I. The Gamble

Let’s start here: the Republican Party is likely to lose control of the House of Representatives this November.

What makes us think that? A bunch of things. It’s what the generic ballot polling tells us. It’s what the results of special elections suggest. And it can be gleaned from the fact that more Republicans are retiring from Congress than Democrats, normally a telltale sign of which party is expecting to lose seats.

But even more fundamentally than any of that, we know that GOP losses are a smart bet to make because the party in control of the White House practically always loses House seats in midterm elections.1 (And, because Republicans currently control a very slim 218-214 House majority, losing seats basically guarantees losing the majority in this context.)

This is sometimes referred to as a “law of political gravity” (see here or here), but this is something of a misnomer. If an apple falls from a tree, it will always fall straight down. There are no ifs, ands, buts, or room for changes depending on human behavior. Presidential midterm losses are clearly somewhat gravitational: we know that voters will sometimes vote against incumbent parties even if they have implemented popular policies, including because the electorate will often vote based on what they assume the party has done in office, even if their assumptions are incorrect.

But there is also good reason to believe that this dynamic is not purely gravitational: that is to say, there is some room for changes based on how humans act or don’t act. Specifically, according to the political scientist Jacob Holt, the more successful a president is in implementing his legislative agenda, the worse his party will do in the midterms. Presidents’ parties fare poorly in midterms at least partly in response to the party overreaching and passing a flurry of bills to advance its ideological agenda; therefore, the more a party passes, the worse they fare at the ballot box.

This presents a dilemma for presidents: husband your political capital, and not really try to pass a legislative agenda, or spend it, even though pushing bills through Congress might mean losing control of the legislature after just two years. Most presidents decide to take this gamble.

This cycle can be seen throughout American history, from Benjamin Harrison imposing sweeping tariffs in 1890 and then losing 93 House seats in that year’s midterms, to Barack Obama passing the Affordable Care Act in 2010 and then losing 63 House seats later that year. Obama never regained control of Congress, but the Affordable Care Act was passed — and still remains law to this day. Obama viewed that as a trade worth making.

Perhaps the paradigmatic example of this is Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and then telling an aide that Democrats had “lost the South for a generation.” In the 1966 midterms, Democrats lost 47 House seats, and the looming Republican dominance in the South started to come into view. The Great Society never returned to the same clip, but Johnson was at peace with his decision. He had lost his stranglehold on Congress, but won the Civil Rights Act.

To be clear, there are presidents who tried and failed to achieve legislative successes before midterm losses, too: Bill Clinton unsuccessfully attempted to pass “Hillarycare,” helping lead to his party’s 54-seat loss in the 1994 House elections. After his 2004 re-election, George W. Bush famously declared, “I earned capital in the campaign, political capital, and now I intend to spend it.” He then spent it trying to partially privatize Social Security; the result was Republicans losing 31 House seats in 2006.

Other presidents’ legislative records have been more mixed. Donald Trump succeeded in passing the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017 (much of which remains in effect to this day); his 2018 midterm losses can be partially attributed to the unpopularity of that measure, as well as to his attempt to repeal Obamacare, which failed. Joe Biden succeeded in passing the American Rescue Plan Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (some of which remains in place, including Medicare drug pricing negotiations that are still moving forward), but came up short in attempting to pass sweeping voting rights legislation.

In each case, though, these presidents took big swings, trying to achieve lasting policy change for their agenda, and then let the chips fall where they may. It can be debated how much of a direct impact a president’s legislative record has on the subsequent midterms — I’m not positing that every voter who voted against Republicans in 2018 did so because of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — but, either way, the last several presidents have recognized that they really only have two years of congressional control guaranteed to them, and have tried to codify as much of their agenda into law as they can in that time.

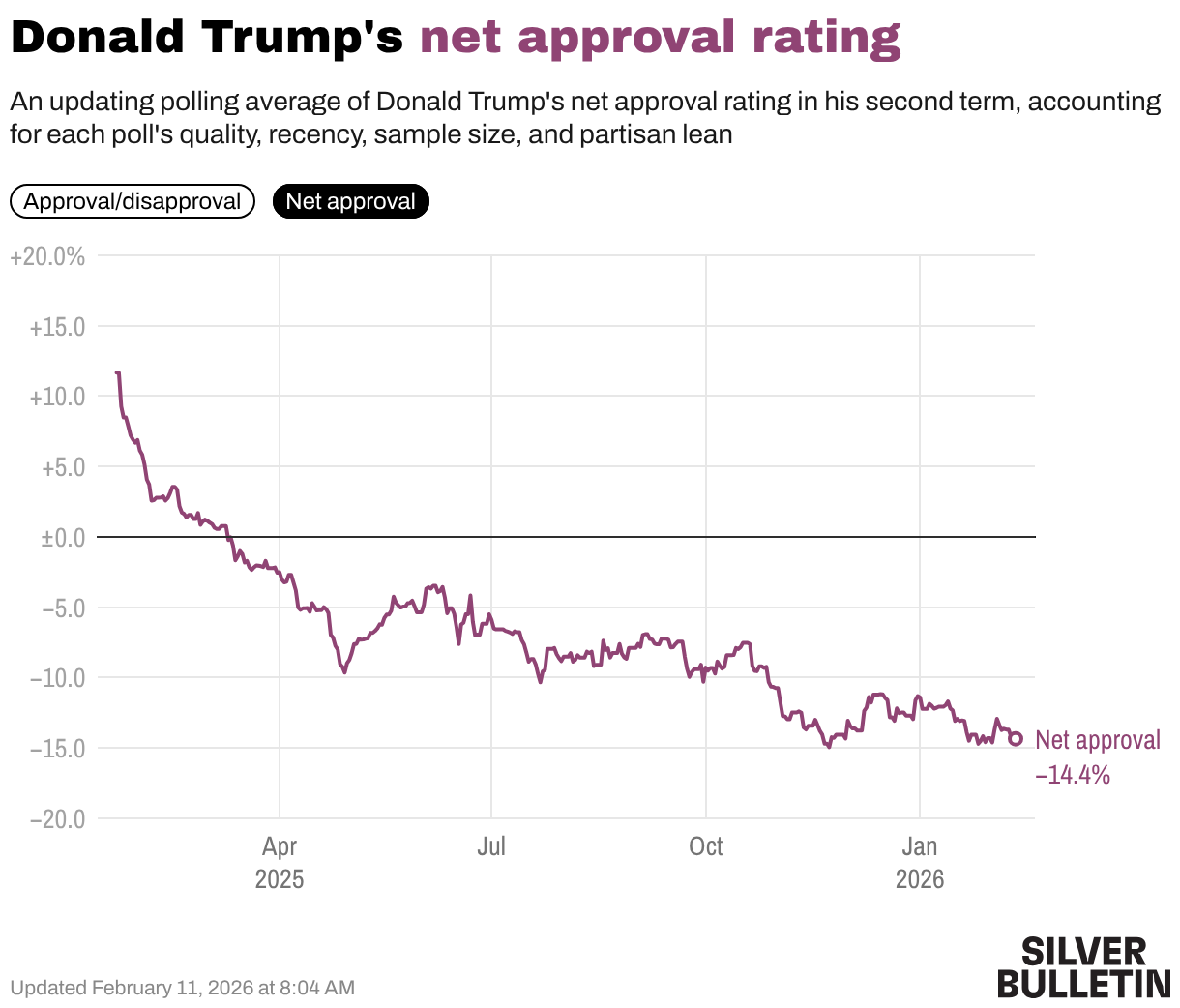

Donald Trump, too, started his second term with political capital, including (for the first time in his career) a positive approval rating. His net approval rating has gone from +11.7% on Day 1 to -14.4% today, so we can tell that he has spent it.

What did he spend it on?

Exactly one piece of major legislation, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which made his 2017 tax cuts permanent, cut Medicaid spending, and funded his immigration push (although, importantly, did not codify any changes to immigration policy into law).

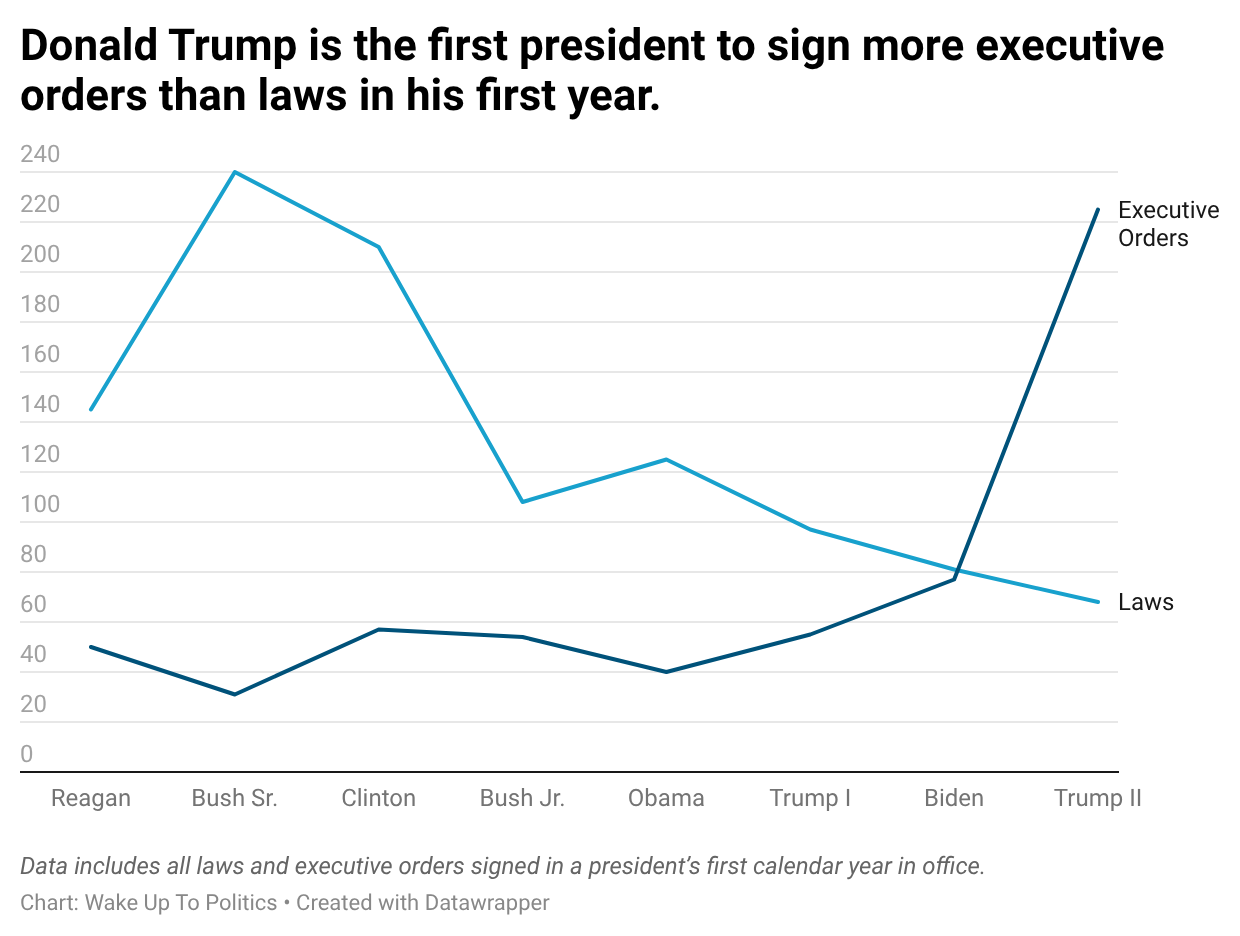

And then a whole host of executive actions. These actions have ranged from tightening the southern border, bringing illegal border crossings almost to a halt, to — just this week — rejecting vaccine approvals and undoing the “endangerment finding” put in place by the Obama administration that has undergirded numerous environmental regulations.

This is a measurably different approach than previous presidents, all of whom have prioritized the legislative process over the issuance of executive orders. And it is one that Trump has openly declared. Just yesterday, Trump was asked if he plans to push for another party-line legislative package, just as he tried to pass two such packages before losing the House in the 2018 midterms, just as Joe Biden passed two such packages before his majority went up in smoke in 2022.

Trump said no. “In theory we’ve gotten everything passed that we need,” Trump told Fox Business Network. “Now we just need to manage it. But we’ve gotten everything passed that we need for four years.” By his own account, he has no more legislative agenda for the entire rest of his presidency.

None of this is to say that executive actions don’t matter: they do, a great deal. They can have a lasting impact on individual people: think of someone who has been deported, for example, or a federal employee whose job has been slashed.

But they have limited impact on long-term public policy, because they are so vulnerable to being overturned by future presidents or by the courts. A regulation that can be lifted by the stroke of a pen can be revived just the same way.

If you think of American public policy as an enormous sandbox, it is legislation that builds the walls of the sandbox, deciding where it will go and how far it will reach. Legislation can also pour cement into the sandbox, mixing with the sand to build structures that harden into concrete, standing the test of time. Executive actions are sandcastles built atop the concrete edifices, interesting to look at (and maybe even consequential) in their time but easily knocked down.

There is a reason presidents have spent down their political capital on things like the Civil Rights Act or the Affordable Care Act, laws that remain in place for decades, changing the country in lasting ways and securing lasting legacies for the presidents who pushed for them. Trump’s theory of the presidency, by contrast, has been that he could build concrete structures out of sand, governing purely through executive orders, without the need for them to be cemented by Congress or anyone else.

That theory has not paid off politically: his political capital has still been spent down; his control of Congress is still expected to expire after the midterms. And it has not paid off in terms of achievements notched in his first two years, since so many of his sandcastles have already been knocked down by judges, from his attempt to change the meaning of birthright citizenship (which has not been in effect for a single day of his presidency) to his executive order to secure more federal control over elections (which has also been repeatedly blocked).

Executive actions are inherently ephemeral, which means — once all the dust is settled — the legacy of his second term will be inherently limited. He will have very little to show for it, in terms of work products that made a lasting impact on the American policy landscape.

Does he care about this? I don’t know. I wrote almost a year ago that it was hard to tell what Trump wanted out of his second term, precisely because he often seems to care more about the trappings of the presidency (a gilded Oval Office, a new ballroom) than the particular policy direction of the country. Jonathan Bernstein recently framed this as Trump having extreme “private ambition,” but strikingly little of the sort of “public ambition” that has generally animated most presidencies.

This makes it harder to compare Trump with other presidents, when he doesn’t even seem to be trying to use his political capital to effect lasting political change. At times, it hasn’t even felt like he’s working in the same sandbox, focusing more on using the presidency to line his pockets and rename things for himself than on the sort of towering public achievements that normally define a presidential legacy and sometimes remain in place for generations.

II. Checks

Because our media climate guarantees that the flashy announcement of a policy will drive more coverage than whatever happens next, you might be surprised by just how few of the sandcastles Trump has tried to build remain standing, even before a successor comes along to wipe them down.

This, of course, is because judges have ruled against them. I’ve written before that a constitutional crisis would emerge if the president ignores these court orders (in other words, if a president insists a sandcastle is a concrete structure, refusing to knock it down when told). Recently, when I referenced this definition, a reader replied with this thoughtful response:

Your analysis of “constitutional crisis” is helpful to me. I am very worried about where we are in this matter and your analysis gives me a more hopeful outlook. But I want to push back a little bit. According to you, a constitutional crisis is one that is primarily (exclusively?) fought in the courts. But there are other crises that generally don’t (as far as I know) end up in the courts. I’m thinking of the emoluments clause, a weaponized DOJ, unfair application of government policy (withholding federal funds from blue states), threatening companies/universities with legal action or withholding money or privileges (security clearance to law firms), etc. The check on most of these issues rely on Congress. But what happens when Congress refuses to check abuses by the president? Aren’t these threats to our democratic system even if they don’t conform to your definition of “constitutional crisis?”

I do think there is something to this; as I’ve written, not every potential threat to our democratic system will be litigated in the courts. Constraining a president’s war powers, for example, is something the courts are likely to leave to Congress. It is also unlikely, as the reader pointed out, that a court would check the president’s efforts to enrich himself via emoluments or other means.

But, as it happens, the other specific examples this reader gave are actually ones that are all being checked by the legal process. To take them in order:

A weaponized DOJ: The Trump administration has attempted to prosecute a slew of its political rivals. Most of those cases are not going particularly well. Charges against former FBI Director James Comey and New York Attorney General Letitia James were both dismissed by a judge who deemed the prosecutor who brought them to have been unlawfully appointed. When the DOJ tried to resurrect the James charge, they were rebuffed by two grand juries. Grand juries have similarly declined to sign off on several charges the Trump administration has sought to bring against protesters — and, just yesterday, a grand jury in D.C. blocked the Trump administration when it tried to level extraordinary changes against six Democratic members of Congress who appeared in a video urging service members to disobey any illegal orders they receive.

Withholding federal funds from blue states: Just in the past few weeks, we have seen a number of cases of judges blocking Trump’s attempts to meddle with federal funds. A judge ruled against Trump’s efforts to defund the Gateway project in New York and New Jersey. Trump also tried to pause five offshore wind projects, in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York. Judges ruled against him on all five. Last week, a judge ruled that Trump must continue funding child care programs in five Democratic-controlled states, at least for now. The list goes on.

Threatening universities with legal action: Some universities, like Columbia and Brown, preemptively decided to sign agreements with the Trump administration, but the main university that did opt to sue (Harvard) has repeatedly found success, including court rulings restoring their federal funding and blocking the administration from preventing the enrollment of international students. Just last week, the New York Times reported that Trump appeared to be changing tack in light of Harvard’s legal victories: he apparently dropped his demand “for a $200 million payment to the government in hopes of finally resolving the administration’s conflicts with the university.”

Security clearances for law firms: Again, there are law firms that opted to strike deals with the administration (Kirkland & Ellis, Paul Weiss, etc.), but the firms that decided to fight against Trump’s threats (Perkins Coie, Jenner & Block, Wilmar Hale, and Susman Godfrey) have all won their cases so far, with federal judges blocking the administration’s attempts to strip the firms of their federal contracts and security clearances.

Here is another question I recently received from a reader:

Can we safely say we are no longer headed toward becoming a Fascist country, but are already there?

The definition of fascism is murky, but Merriam-Webster tells us that it is “associated with a centralized autocratic government headed by a dictatorial leader.” Whatever one might say about how Donald Trump would like to run the U.S. government, given his druthers, I think it is a hard case to make that he is currently leading an “autocratic government” (rule by one person), or heading in that direction, when so much of what he has tried to do has been halted by the courts or, in the cases of immigration enforcement in Minnesota (where ICE forces have been reduced and ordered to wear body cameras) or tariffs related to Greenland, reversed under public pressure.

Unlike an autocrat, who rules by fiat, Trump is constantly being checked (and, importantly, listening when he is being checked, also not a common sign of an authoritarian). These checks should impact one’s analysis of the strength of American institutions, but also the strength of Donald Trump, and the success of his presidency, which has sparked a lot of sound and fury, but little that is poised to survive him.

Some of Trump’s most notable uses of executive power have been his attempts to not even work within the sandbox Congress has provided him, but to instead try to dig outside of the sandbox and expand its boundaries unilaterally. I’m thinking here, for example, of Trump’s attempts to interfere with the power of the purse, long understood to be the exclusive province of Congress.

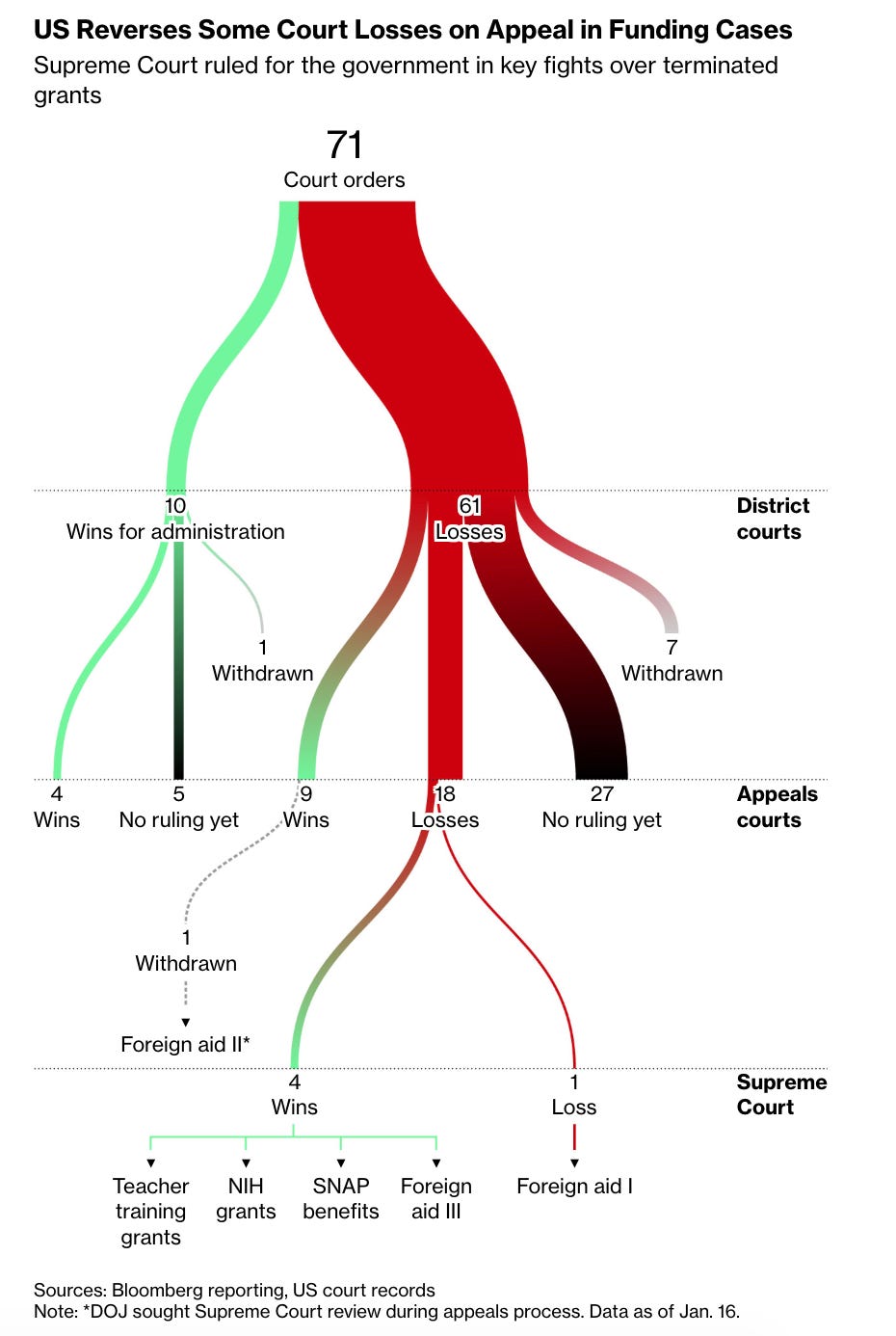

As the below graphic by Bloomberg shows, this has largely been a losing battle. Just as he has lost a majority of court cases overall, Trump’s funding cases have mostly generated losses for him. (Trump has won all four of these cases that he has appealed to the Supreme Court on an emergency basis — but, notably, he opted not to rush his 57 other losses to the justices, perhaps a sign that he views the other cases as losing battles.)

There have also been signs of Congress defending its power of the purse in subtle ways, rebuffing many of Trump’s proposed cuts in the recent appropriations packages and also adding guardrails to the bills to prevent Trump from making changes unilaterally.

III. Persuasion

Why has Donald Trump chosen to build sandcastles? Why gamble away your political capital without getting much of anything in return?

Because building lasting structures is hard. It requires going through Congress: striking deals, twisting arms, catering to other people’s needs and interests. Despite the title of his bestselling book, Trump has shown little interest in this sort of legislative negotiation in either of his terms. He much prefers the fanfare of signing executive orders, doing things himself and creating the illusion (which many of his critics seem to have bought into) that he is running a one-man government.

Sure, that might not lead to much in the way of lasting change — but if you’re someone who isn’t much interested in the state of public policy anyway, then who cares? In that context, this trade (receiving personal aggrandizement, but not lasting policy change) might seem more valuable than the normal presidential trade (receiving lasting policy change, but losing control of Congress) — although, of course, Trump is likely to lose control of Congress anyway, since his (fragile) executive actions haven’t been any more popular than other presidents’ (permanent) laws, so really he is getting the worst of both worlds, in exchange for the temporary (but clearly inaccurate) feeling that he runs the country like a one-man behemoth.

Of course, one striking feature of all this is that we pay several hundred people to write those permanent changes to public policy we call laws, and many of them have been content with surrendering their powers to the president (beyond the occasional grousing to the media about not having many legislative accomplishments to run on in 2026.)

Yesterday, House Speaker Mike Johnson said the quiet part out loud, acknowledging that public policy in the U.S. has largely become a conversation between two out of our three branches of government: everyone, that is, but the branch that he (theoretically) is supposed to lead and protect the interests of.

Johnson argued that the House should block votes on the president’s sweeping tariffs (imposed through a legally vulnerable interpretation of a 1977 law) in order to “allow a little bit more runway for this to be worked out between the executive branch and the judicial branch,” as the speaker put it. The legislative branch, endowed with taxing powers by the Constitution, need not get itself involved.

When he said this, Johnson was urging his colleagues to block (for the third time) the ability of Democratic lawmakers to force House votes on measures that would undo Trump’s tariffs. (Back in March, the first time the House did this, I covered the procedural mechanics behind the move. That block expired in September, at which point the House extended it until January 31. Yesterday’s vote was about extending the block through the end of July.)

Notably, Johnson (and Trump) were not successful in this. Three Republicans — Reps. Don Bacon (NE), Kevin Kiley (CA), and Thomas Massie (KY) — voted against the measure, dooming it to defeat.

As a result, Democrats will now be able to force vote after vote on Trump’s various tariffs, likely starting with a vote on his Canada tariffs today. Despite the best efforts of the president, and of the branch’s own leader, the legislative branch is throwing itself back into the conversation on trade policy, due to the votes of a trio of Republicans.

In his 1991 book “Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents,” Richard Neustadt — one of the most influential scholars on the American presidency — argued that the presidency, by itself, is quite weak in the American system. Because the president shares authority with so many others, the source of a president’s power, Neustadt argued, is their power to persuade.

“When one man shares authority with another, but does not gain or lose his job upon the other’s whim, his willingness to act upon the urging of the other turns on whether he conceives the action right for him,” Neustadt wrote. “The essence of a President’s persuasive task is to convince such men what the White House wants of them is what they ought to do for their sake and on their authority.”

By this metric, Donald Trump is not very strong. He has not persuaded Congress to pass many bills (indeed, knowing that it would be hard, he has largely not even tried). He has not persuaded the Senate to eliminate the filibuster. He has not persuaded grand juries to let him prosecute political rivals. He has persuaded the Supreme Court to let him fire key officials in the executive branch, but he has not persuaded the justices (so far) to sign off on his much more expansive asks: deploying federalized National Guard troops to American cities (all have been removed as of today), sending migrants to foreign prisons without due process, firing a governor of the Federal Reserve. Potentially, I’ve argued, he hasn’t even persuaded the Republican Party to adopt his vision for the party in lasting ways (partially because he doesn’t have one).

These were all big swings; many were swings he wanted to take unilaterally, to make his sandbox larger without congressional approval. On each score, he’s been rebuffed.

Yesterday’s tariff vote is a double mark of his persuasive weakness. Most obviously, it shows weakness because he failed to persuade enough Republican lawmakers to block votes on his tariffs. But the fact that he was even asking for votes on the tariffs to be blocked — regardless of whether that ask was granted — proves that he has not persuaded enough lawmakers in his party to support his signature economic policy, because you don’t need to block votes if you’re confident you’ll win them.

The fact that Trump was trying to avoid congressional votes on the tariffs goes to show either that he has not persuaded enough Republicans to affirmatively support the tariffs if they come up for a vote — or that he has not persuaded enough of the public, such that it is known across Washington that any Republican casting such a vote will be undergoing a politically toxic exercise.

But without legislative support, the tariffs are — like almost everything else — a sandcastle, potentially on the verge of being knocked down by the Supreme Court, or the next Democratic (and maybe even Republican!) president if not.

Neustdat believed that a president’s persuasive ability relies in part on public opinion being on their side, what he referred to as “public prestige.” Public opinion and congressional support is bidirectional: the more popular a president is, the more likely it is Congress will enact his policies — but also, oftentimes, the more a policy is given the support of Congress (a public forum where issues are hashed out and broad-based majorities are cobbled together), the more likely the public is to view the policy change as legitimate, the more likely it is to stand the test of time.

Trump, of course, is highly unpopular. The considerable opportunity he had, at the beginning of his presidency — when he was popular, and even some Democrats believed they would have to adopt parts of his agenda — to use his two years of united government to place a permanent stamp on public policy (perhaps an immigration bill? Or a voter ID deal?) is quickly waning, and he doesn’t seem to care.

He has admitted he has no legislative agenda for the next three years. And, a person close to the White House told the Washington Post, he doesn’t even care much about losing the midterms. (Indeed, when he has worried aloud about losing in November, it has usually been about his personal risk of impeachment, rather than for any larger policy agenda.)

The political scientist Matthew Dickinson, a student of Neustadt’s, recounted in 2022 that he once asked his mentor about how to consider “a president’s decision to ‘go big’ legislatively at the cost of a governing majority,” as so many presidents have done.

“His reply: the best a president can do is understand the long-term cost of going big, and decide whether the immediate legislative objective is worth that cost,” Dickinson recalled. “Only a president can make that judgment.”

What is unusual about Trump is he has undeniably “gone big” at the cost of a governing majority — but mostly in the service of private goals, and the temporary appearance of personal power, not for any long-term legislative accomplishments. He will soon lose his governing majority, but he has not gotten a Civil Rights Act or Affordable Care Act or anything close out of it. He has flipped the normal gamble on its head.

In the short-term, this has created the appearance of utmost power, which seems to satisfy what Trump wanted out of his second term. In the long-run, it has given him nothing but a bunch of crumbling sandcastles.

There have only been two exceptions, 1998 and 2002, since World War II. There have only been five exceptions (1866, 1902, 1934, and the aforementioned) in the 41 midterm elections since the Civil War.

Very well written. There are true checks to presidential power by design, despite the expansion of its scope by every president since Washington.

The real story I’m interested in is Congress. They were designed to be primary, with their own checks and balances in the bicameral setup to ensure deliberation and alignment.

Our current Congress is constantly running for re-election to a great job with amazing perks. They also seem more like influencers and personal brands than legislators.

I’d like for them to rise to the occasion and reclaim their role within the government.

This was well worth the read, and more than worth the subscription cost. Thank you.