The Presidents Who Refused to Name Things After Themselves

Trump’s naming bonanza reverses a long presidential tradition.

Gerald Ford faced a dilemma.

Five days after he ascended to the vice presidency, lawmakers unveiled a bill to rename a federal building in Ford’s hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan, in his honor. Although Ford was a Republican, the bill was introduced by a Democratic congressman, and eventually approved unanimously by both chambers of Congress, a mark of the esteem in which lawmakers held Ford, their former colleague of 25 years.

“I look upon Jerry Ford as an honest man, as an intelligent man, as a fair man, and as a patriotic man. He is a great American of whom all of us are proud,” one Democrat said at a hearing considering the bill, noting that “the fact that we have not always seen eye-to-eye in [no way] limits my respect or friendship” for the vice president.

Except, by the time Congress had finished approving the bill, Ford wasn’t the vice president anymore: he was the president. (Whether this reflects how slowly Congress moves to pass even uncontroversial legislation, or how quickly the Nixon presidency unraveled, is in the eye of the beholder.) Was it appropriate for the president to sign into law a bill naming something for himself?

The White House budget office, which normally takes point on recommending to the president whether he sign or veto bills, thought it would be fine, but Ford ultimately decided to “pocket veto” the legislation, letting it die without becoming law.

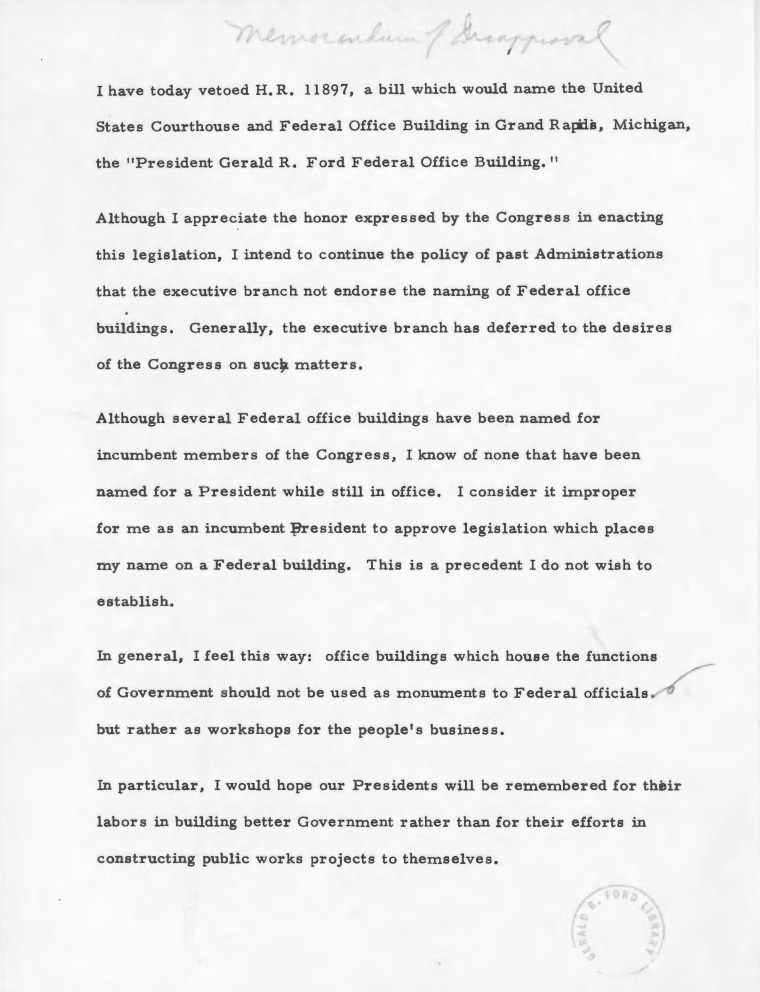

“Generally, the executive branch has deferred to the desires of the Congress on such matters,” Ford acknowledged in a veto statement. “However, I know of no Federal office buildings that have been named for a President while still in office. This legislation might begin a precedent I believe it best not to establish.”

“The proposed naming of this facility for me in my home community is a great honor, and one for which I am deeply grateful; however, for the reasons I have assigned above I feel I cannot sign H.R. 11897,” Ford continued.

According to a 1980 study, it was the first time in years that a president had disregarded the “unanimous” advice of the budget office and other executive branch agencies on whether to sign a bill. Buried deep in the Ford Library archives, there is an earlier draft of Ford’s statement, which has never been previously reported on, sounding an even more pointed note.

“In general, I feel this way: office buildings which house the functions of Government should not be used as monuments to Federal officials, but rather as workshops for the people’s business,” Ford was to say in the initial draft. “In particular, I would hope our Presidents will be remembered for their labors in building better Government rather than for their efforts in constructing public works projects to themselves.”1

Fifty years later, it would appear that the White House policy on presidents “constructing public works projects to themselves” has undergone a stark reversal.

According to several news outlets, not only is President Trump pressuring congressional leaders to name two large pieces of public infrastructure after him: he has threatened to hold up funding for a third infrastructure project until his demands are met.

During the government shutdown in October, Trump froze $16 billion in federal funding for the massive Gateway project, which includes construction of a new rail tunnel connecting New York City and New Jersey and rehabilitation of the existing tunnel, which dates back to 1910 and is in poor condition, frequently creating delays in an economically vital area. Trump’s move was widely seen as retaliation against a pair of Democratic-led states over the shutdown.

Last week, Trump reportedly made Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) an offer: he would release the funding for the Gateway project, if Schumer agreed to support naming Washington, D.C.’s Dulles Airport and New York’s Penn Station after Trump.

According to Punchbowl News, Trump has also specifically said he wants the airport code at Dulles to be changed from “IAD” to “DJT.”

Schumer declined the offer, with a spokesperson telling Punchbowl that “there’s nothing to trade,” seeing as the Gateway funding has already been statutorily approved and (in Schumer’s view) Trump doesn’t have the power to freeze it anyway. Trump then claimed that it was Schumer’s idea to rename the country’s busiest train station “Trump Station.” Schumer said that was an “absolute lie”; either way, the issue is now moot after a federal judge ordered Trump to release the Gateway funds on Friday.

Still, the request — however short-lived — was extraordinary. While Gerald Ford humbly declined when Congress tried to name a building after him, Donald Trump is actively pushing for his name to be stamped on two major American structures … and holding up an important piece of public policy to do it.

Officials in New York and New Jersey said the Gateway funding freeze was putting approximately 1,000 construction jobs in jeopardy, which means Trump was effectively gambling with American jobs in pursuit of putting his name on a train station and an airport.

Of course, this is not Trump’s first attempt to use his second term to place his name on institutions new and old. The president who licensed everything from Trump Hotels to Trump Steaks during his time in the business world has, over the last year, debuted “Trump Accounts” (for children) and the “Trump Gold Card” (for immigrants), announced a new “Trump-class battleship,” and claimed that the Kennedy Center is now “The Donald J. Trump and The John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts” and the U.S. Institute of Peace is now the “Donald J. Trump Institute of Peace.” (Congress has not codified either of the last two name changes.)

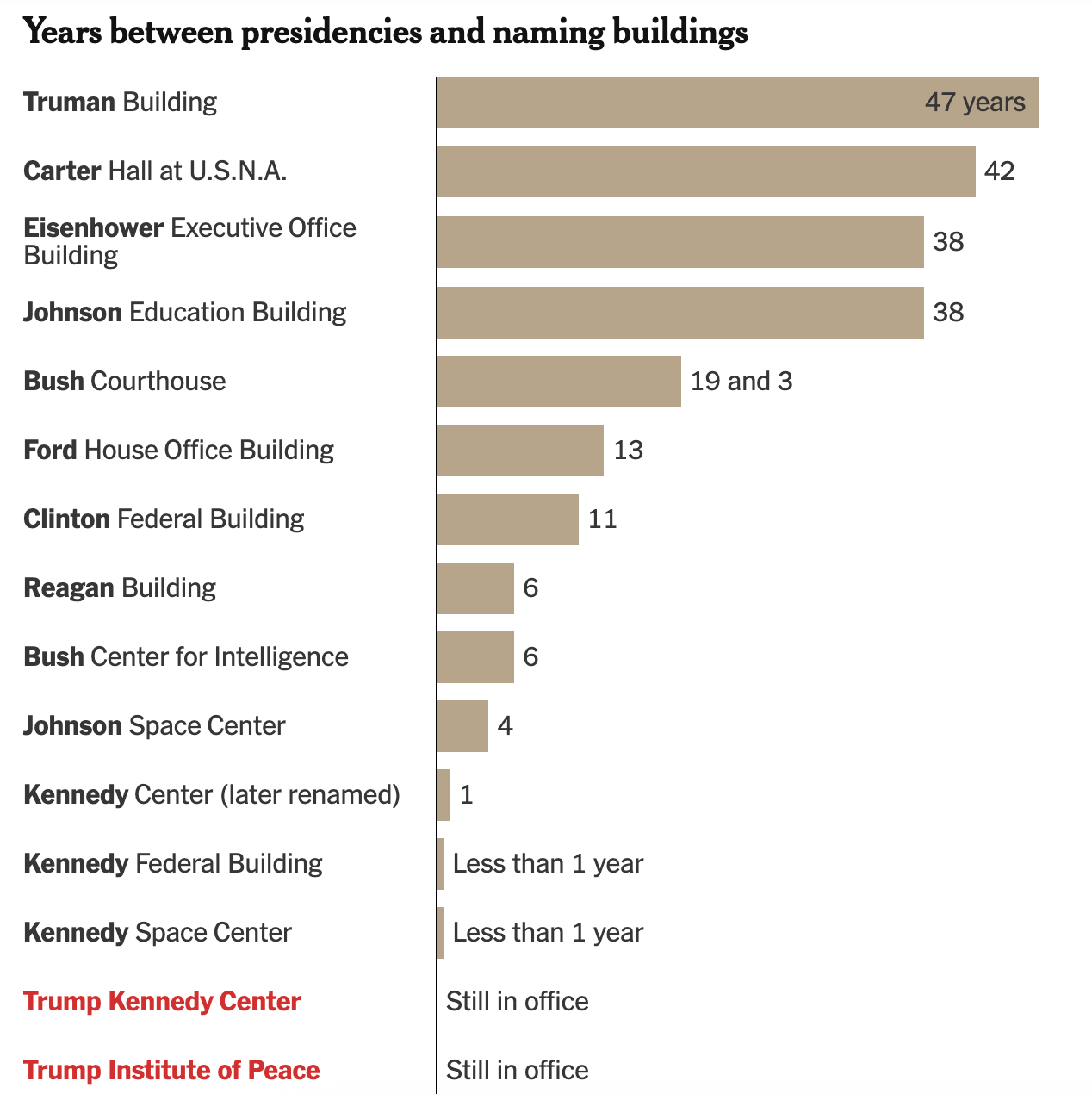

Trump’s naming bonanza is without precedent in American history: most previous presidents have shied away from placing their names on buildings or other projects, waiting until after they leave the White House to accept such honors, as the below New York Times graphic shows.

When a local newspaper advocated for the renaming of a road in his Missouri hometown after him during his presidency, Harry Truman wrote a letter to the editor declaring, “I have no desire to have roads, bridges or buildings named after me.” More consequentially, Truman also demurred when a top adviser recommended that he name his signature European foreign aid program the “Truman Plan.”

“We have a Republican majority in both houses [of Congress],” Truman said. “Anything going up there with my name will quiver a couple of times, turn belly up, and die.” Truman ultimately decided the policy should carry the name of the popular World War II general George Marshall: “The worst Republican on the Hill can vote for it if we name it after the general,” the president concluded.

Prioritizing the success of an important policy over his own legacy, Truman passed on the chance to be personally tied to one of the most famous foreign-relations efforts in American history — the soon-to-be-named “Marshall Plan” — in order to ensure that the proposal would receive bipartisan support and pass.

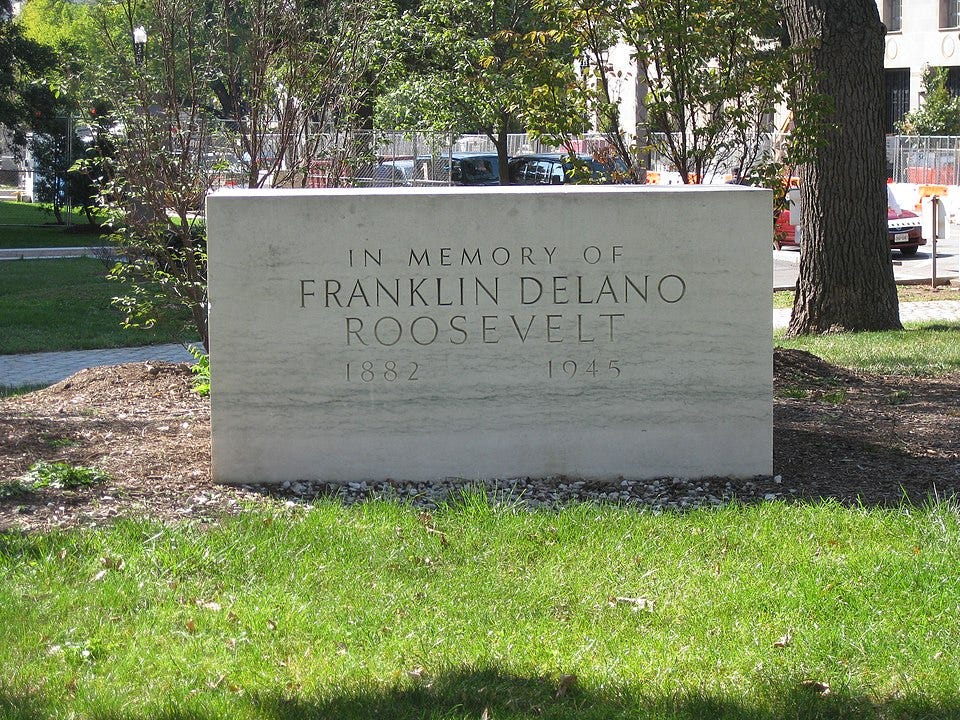

Truman’s predecessor, Franklin Roosevelt, also viewed it as unseemly for presidents to construct ornate monuments to themselves. “If any memorial is erected to me, I know exactly what I should like it to be,” Roosevelt once told Justice Felix Frankfurter. “I should like it to consist of a block about the size of this [desk] and placed in the center of that green plot in front of the Archives Building. I don’t care what it is made of, whether limestone or granite or whatnot, but I want it plain, without any ornamentation, with the simple carving, ‘In Memory of…’”

Roosevelt’s request was only partially granted: he is now the subject of the largest presidential memorial on the National Mall, dedicated in 1997 and sprawling out over almost eight acres. But if you walk by the National Archives building in D.C., you’ll also see the simple block of marble that was dedicated to FDR decades earlier, in keeping with his wishes, a monument to presidential humility.

None of this is to say that Donald Trump is the first president to have things named after him while in office. Schools and highways were already being named for Barack Obama during his presidency. Perhaps most notably, Washington, D.C. was named for George Washington while he was in office. (There is not much record of how he felt about the choice.)

On Capitol Hill, it should also be noted, it is not uncommon for lawmakers to direct federal funding towards projects in their states, only for those projects to be named after them. When the late Sen. Robert Byrd (D-WV) died in 2010 after 51 years in office, his New York Times obituary noted that a trip around West Virginia could take you to “the Robert C. Byrd Highway, two Robert C. Byrd federal buildings, the Robert C. Byrd Freeway, the Robert C. Byrd Center for Hospitality and Tourism, the Robert C. Byrd Drive and the Robert C. Byrd Hardwood Technologies Center.” (Byrd is quoted as having said in his defense: “I lost no opportunity to promote funding for programs and projects of benefit to the people back home.”)

But presidential administrations have rarely tried to recreate this habit for commanders-in-chief — and when they have, it’s reliably stirred controversy.

In 1930, Interior Secretary Ray Wilbur announced that a forthcoming infrastructure project on the border of Arizona and Nevada would be named for the sitting president: the Hoover Dam.

Hoover was “the great engineer whose vision and persistence” had “done so much to make [the dam] possible,” Wilbur said, not unlike the White House spokesperson who recently said the new Trump renamings are to commemorate “historic initiatives that would not have been possible without President Trump’s bold leadership.” (Wilbur also cited a supposed precedent of dams being named for presidents, pointing to the Coolidge Dam and Wilson Dam as examples.)

Hoover’s congressional allies quickly introduced bills to codify the name, sparking controversy on the Hill. Sen. Pat Harrison (D-MS) accused Sen. Reed Smoot (R-UT) of introducing such a bill as a way to curry favor with Hoover in order to promote his infamous Smoot-Hawley tariff measure.

“It comes with fine grace from the Senator from Utah, who is laboring so zealously here now with his colleagues to increase the tariff on sugar, and after he has written into the bill higher rates on wool, knowing that the bill is going to the president of the United States, either for his approval or rejection, to court friendship with the president of the United States,” Harrison said on the Senate floor.

Smoot replied that the name “Hoover Dam” made more sense than the name the project had previously gone by, “Boulder Dam,” since the dam was no longer being built in nearby Boulder Canyon. “Why call it Boulder Dam when it is not to be in Boulder Canyon? It was moved to Black Canyon,” Smoot pointed out. (To this, Nebraska Sen. George Norris interjected: “If the Senator thinks it should not be named ‘Boulder’ because it is not in Boulder Canyon, why does he try to convince us that it ought to be named ‘Hoover’? Is it in Hoover Canyon?”)

Hoover reportedly opposed the moniker, but Congress did eventually start referring to it as the “Hoover Dam” in appropriations bills — though, in a cautionary tale for parties who try to ram through namings for sitting presdients, FDR’s administration ordered that it be called the “Boulder Dam” as soon as Hoover left office.

Partisan pettiness fades over time, however, and Hoover eventually rehabilitated his tattered reputation, working across party lines to help Truman feed Europe after World War II (laying the groundwork for the Truman Marshall Plan) and reorganize the executive branch.

In 1947, Truman signed a bipartisan bill into law officially naming the dam for Hoover.

The story goes to show that it’s not unusual for America to honor its presidents in big and lasting ways, but it normally requires waiting at least a bit after they leave office. With enough patience, though, former presidents are often honored even by their onetime adversaries.

Days after Gerald Ford left the White House in 1977, vanquished by Jimmy Carter, lawmakers tried again to name the federal building in Grand Rapids after Michigan’s favorite son. This time, the bill was approved without a hitch: Carter, his former rival, signed the measure into law. Ford’s name has graced the building ever since.

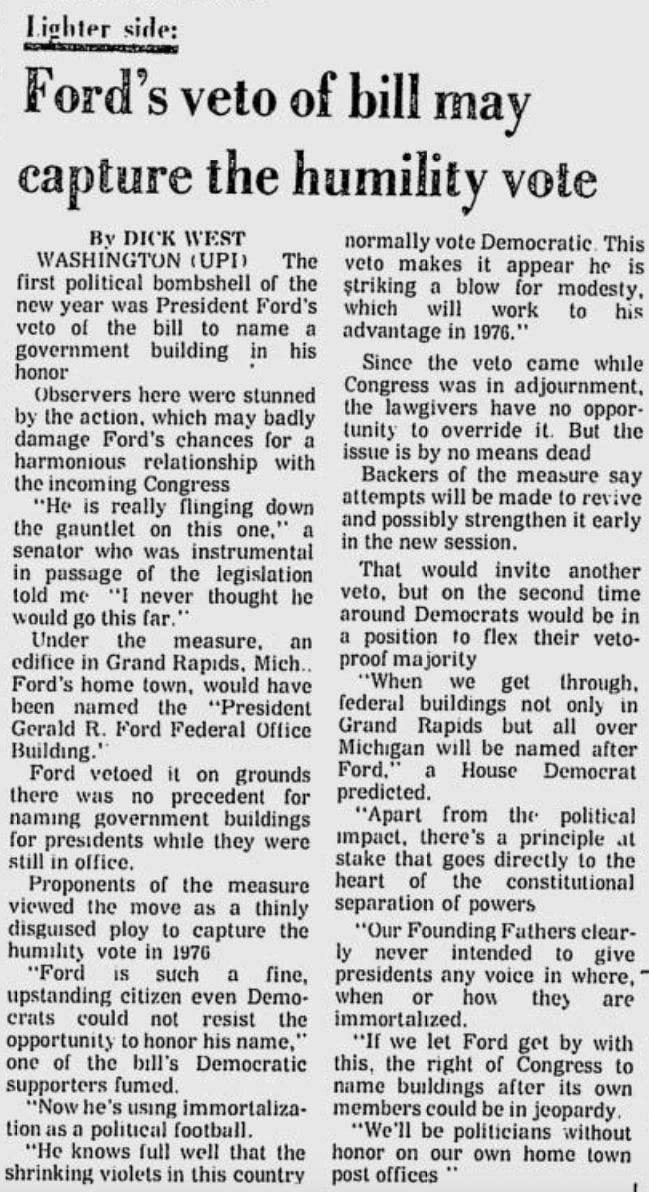

It is unclear why those lines were deleted from the statement, although another file in the Ford archives shows one White House aide sending the draft to another, asking for extra review since this veto in particular “lends itself to side-bar treatment by the media.”

That prediction was correct: the syndicated humor columnist Dick West soon poked fun at Ford’s veto in newspapers across the country, jokingly describing the move as a “thinly disguised ploy to capture the humility vote in 1976,” when Ford would be up for re-election. “He knows full well that the shrinking violets in this country normally vote Democratic,” West quoted a fictitious lawmaker as saying. “The veto makes it appear he is striking a blow for modesty, which will work to his advantage in 1976.”

Can’t Congress find a toxic waste storage area to name after DJT?

I love these kinds of columns so much more than simply a breathless analysis of the latest scandal or the latest political intrigue, which is what most of the rest of political newsletters offer today (although there is a rightful place for those types of newsletters too when done properly - like Chris Cillizza's analyses). No worries if this change allows you to do only 3 newsletters per week -- much more overall value for the reader over a week from this kind of meaningful, insightful content. Well done, Gabe!