A Reader’s Guide to the Big Beautiful Bill: Part 6

Congrats, you’ve read a whole bill!

We’ve finally made it: Our last reader’s guide of the Big Beautiful Bill!

Together, we’ve walked through how the package will impact agriculture, food stamps, and defense in Part 1; banking, commerce, and transportation in Part 2; energy and the environment in Part 3; taxes in Part 4; Medicaid in Part 5; and now, education and immigration in Part 6.

When I was getting ready to publish Part 1, I was worried that no one would be interested in reading through the whole bill, section by section. Instead, these have been some of the most popular Wake Up To Politics features I can remember! So thanks for coming on this journey with me. Sometimes, to really understand something, you just have to read it!

I hope you’ve learned a lot from these columns about the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), about the various arms of the U.S. government, and about how to read a piece of legislation. I know I’ve learned a lot by writing them!

Without further ado, let’s finish reading the Republican budget bill:

Title VIII: Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (pp. 262-286, link)

OK, let’s start with the entire section and then break it down together!

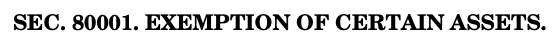

As always, we go to the part of U.S. Code that’s being amended (because that’s more up-to-date than the statute). In this case, that means heading to 20 U.S.C. 1087vv(f), not the text of the Higher Education Act.

Once we arrive at that subsection, we see that it defines what does and doesn’t count as an asset for purposes of calculating a family’s eligibility for federal college financial aid.

The OBBBA tells us to add to paragraph (2), so as of July 2026, not only will the value of a family’s principal residence not count towards their wealth when determining aid eligibility, but neither will a family farm they reside on, a small business they own with fewer than 100 employees, or a commercial fishing business they own.

And we’re off to the races!

There are two types of federal student loans offered to graduate students:

Stafford Loans (named for former Vermont Sen. Robert Stafford, also the namesake of the key disaster relief statute), which are capped at $20,500 per academic year.

Grad PLUS Loans, which students can use after they max out their Stafford Loans to help pay for the rest of their graduate education. These loans have a higher interest rate and require a credit check.

The first important change in Section 81001 is this:

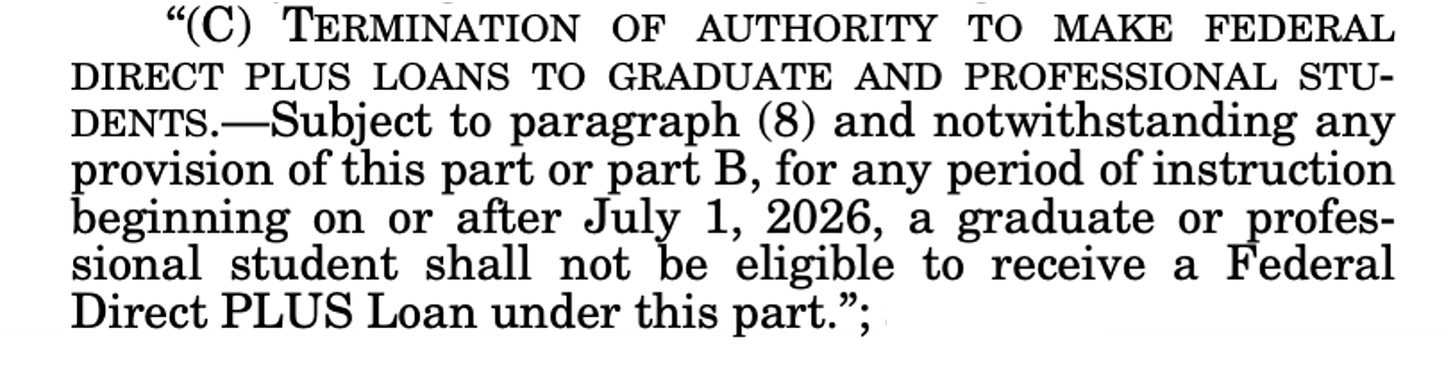

Scratch what I said before. There will soon be only one type of federal student loan available to graduate students; the above provision eliminates the Grad PLUS program starting in July 2026.

The next change in the section will impact Stafford Loans or graduate students:

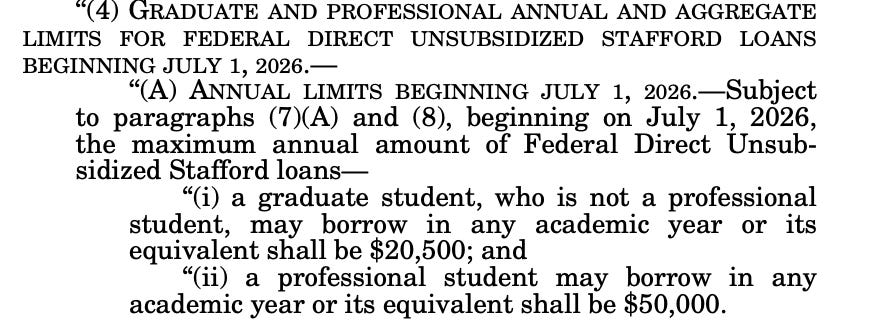

As mentioned, the limit for graduate Stafford loans was already $20,500, so the big change here is raising the limit to $50,000 per academic year for “professional students.” (The OBBBA also sets a lifetime loan cap of $100,000 for graduate students and $200,000 for professional students.)

What are professional students? The OBBBA directs us to Title 34, Section 668.2 of the Code of Federal Regulations, which basically lets us know that doctors and lawyers will be the ones eligible for higher federal loans.

The next part of the section impacts Parent PLUS Loans, which parents can take out to cover the costs of their children’s undergraduate education. Those loans don’t currently have a limit; starting in July 2026, the OBBBA will set a $20,000-per-child annual limit and a $65,000-per-child lifetime limit for these loans.

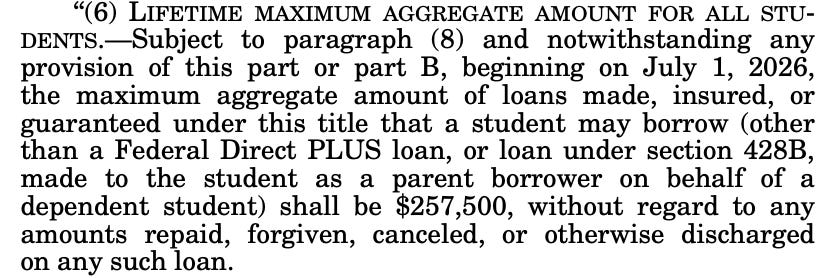

Finally, this section also sets a lifetime limit of $257,000 for the Stafford Loans any student can take out over the course of their academic careers, for both graduate and undergraduate education.

Importantly, any loan recipient who is enrolled in an undergraduate or graduate program as of June 30, 2026 will not be subject to the new limits for the following three years.

Let’s say you took out federal student loans to go to college, and then you graduate. What happens now? Currently, the government offers seven different repayment plans you can sort through, including the SAVE Plan unveiled during the Biden administration. (The Education Department offers a tool to compare all seven here.)

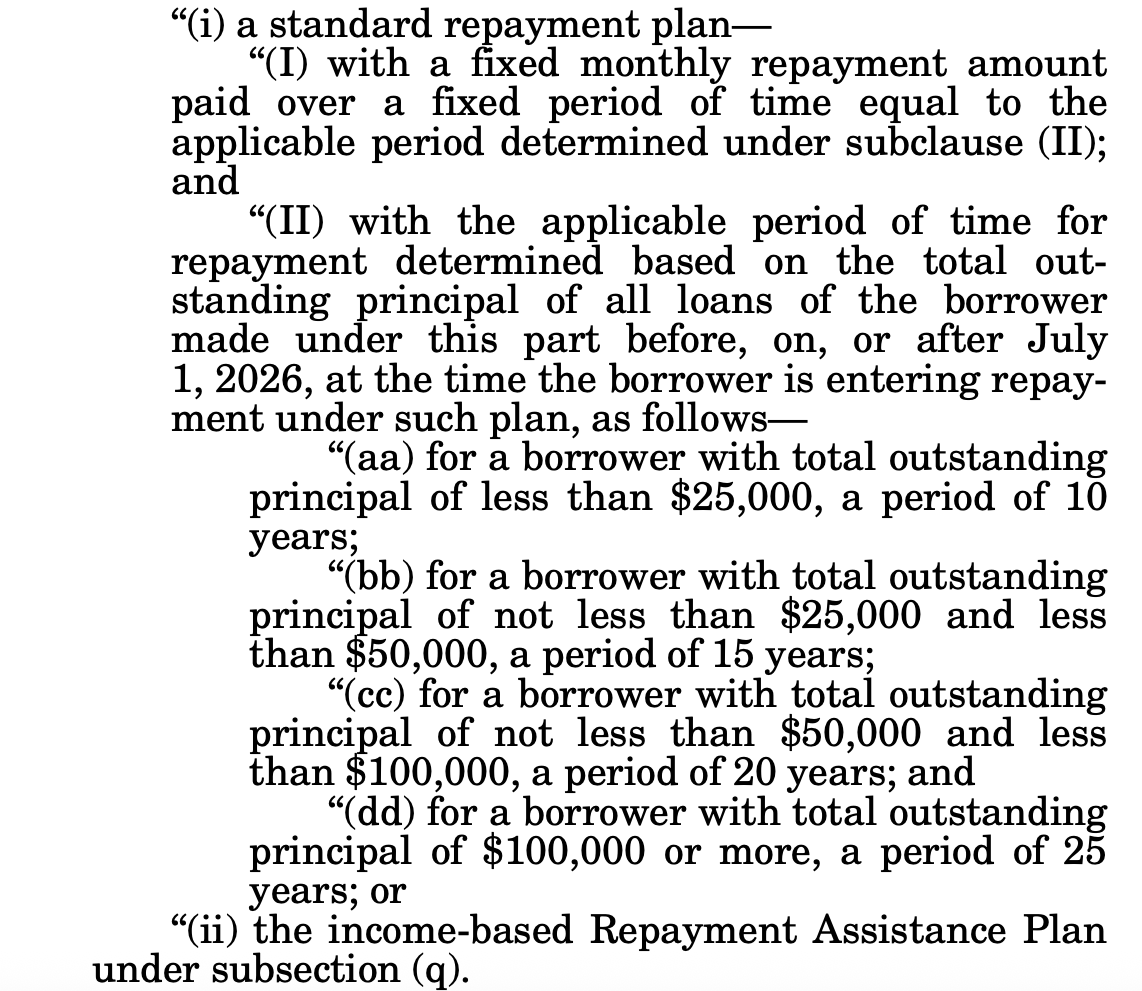

The OBBBA will put a more simplified system in place. Starting in July 2026, borrowers will only have two repayment plans to choose from:

So, the options will be a “standard plan,” where the borrower repays a fixed amount over a fixed number of years, and a new income-based plan (known as the Repayment Assistance Plan, or RAP) created by the OBBBA.

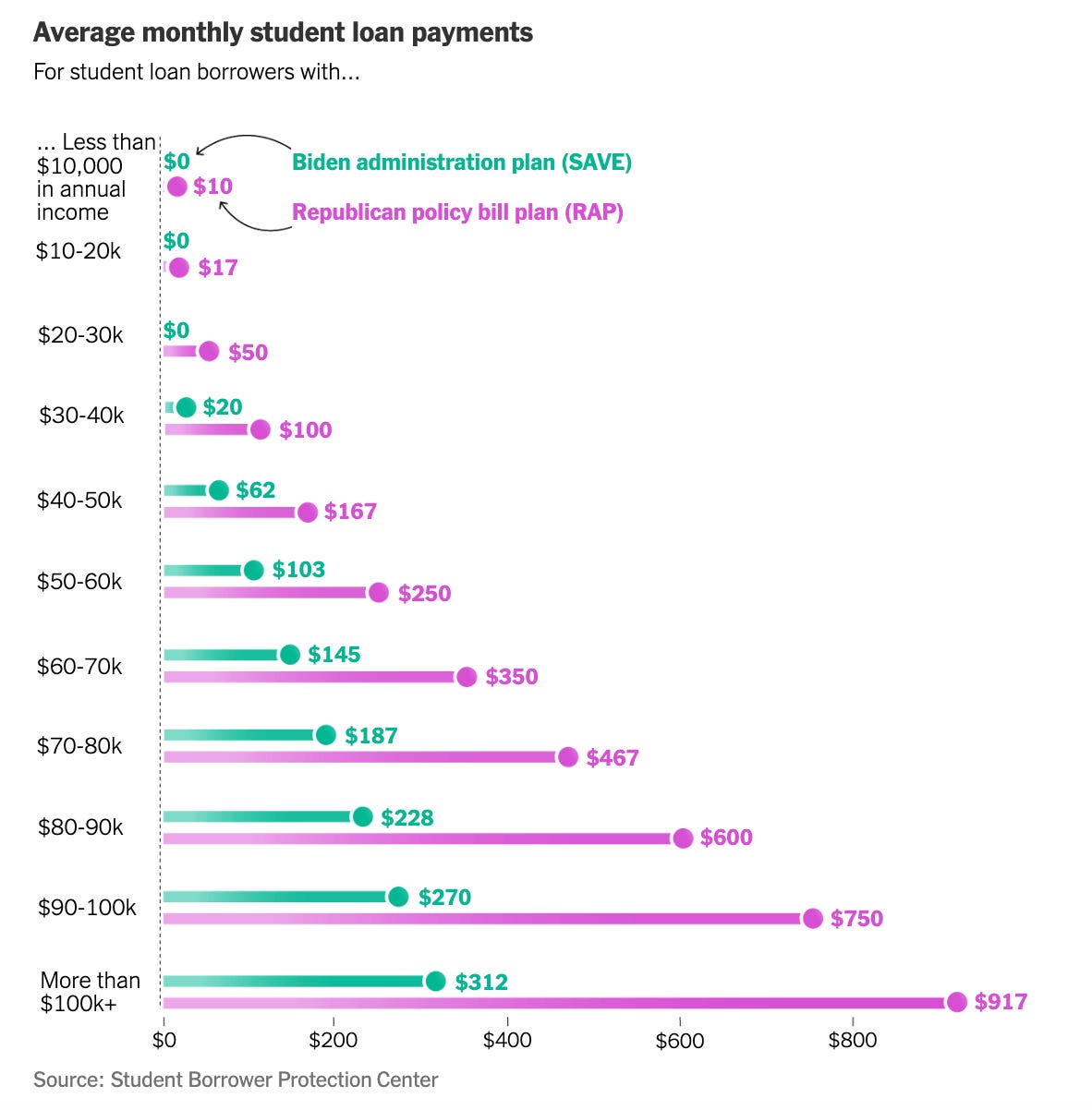

Here’s a chart, via the New York Times, that compares the average monthly student loan payments for each income group under the RAP, compared to SAVE, the income-based plan rolled out under Biden:

Borrowers currently using the SAVE Plan (which has been blocked in court) will have until July 2028 to switch over.

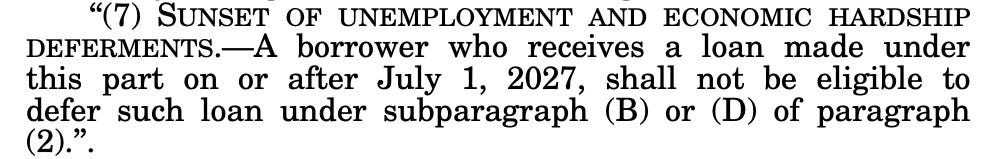

Currently, federal student loan borrowers can qualify for eight different types of deferments, during which they don’t have to make payments on their loans. The Cancer Treatment Deferment and the Military Service and Post-Active Duty Student Deferment are some examples.

Under the OBBBA, starting in July 2027, two of those deferment types will be eliminated:

The Unemployment Deferment is available to borrowers who receive unemployment benefits or those who are looking for full-time work and can’t find it. The Economic Hardship Deferment is available to those who receive welfare benefits, who work full-time but only make minimum wage (or 150% of the poverty wage in their state), or are serving in the Peace Corps. Both deferments can last up to three years.

Democrats say ending these deferments will lead to more borrowers defaulting on their debt. But Republicans say it will steer more borrowers towards enrolling in income-based repayment plans they can afford, rather than plans they won’t be able to. Under an income-based repayment plan, many of the people who qualify for these deferments would already owe monthly payments of $0 during their period of economic difficulty.

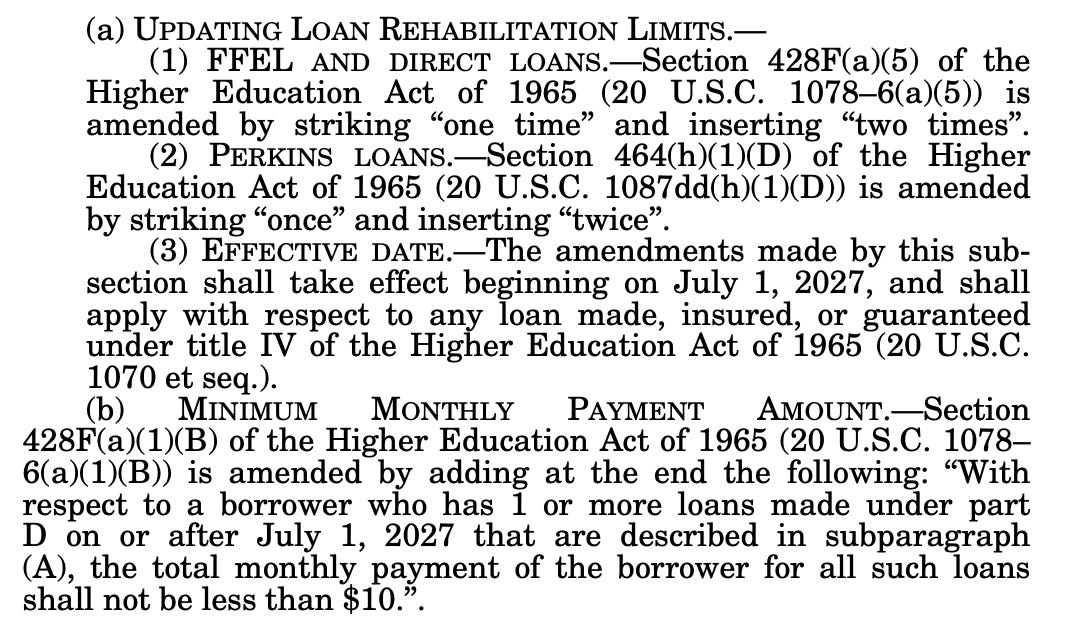

If you’ve defaulted on your loan debt, you can get out of it through a rehabilitation agreement, in which you make nine consecutive, on-time payments, in exchange for the default being wiped from your credit history.

This section would increase the minimum payment required for rehabilitation from $5/month to $10/month — but it would also allow borrowers to rehabilitate their debt twice over the lifetime of the loan, instead of only once.

Now we’re dealing with Pell Grants, a type of student aid for low-income students, named for former Rhode Island Sen. Claiborne Pell.

This section essentially tries to ensure that people who don’t really deserve Pell Grants aren’t getting them. The first way it does that is by clarifying that foreign income counts as income for the purposes of calculating Pell Grant eligibility.

The second thing it does is address a group of people known as “Pellionaires,” who take advantage of the fact that minimum Pell Grant eligibility is based on income, not assets. These are wealthy people who have a lot of assets, but low taxable income (often because of business losses), which lets them game them system and still get Pell Grants.

Under the OBBBA, anyone with a high enough level of income and assets would be disqualified from receiving a Pell Grant.

This section creates a new program called “Workforce Pell Grants,” which expand the Pell program to include low-income students who are enrolled in “workforce programs,” which are shorter and less expensive than a four-year degree and often train students for skilled trade jobs, like working as an electrician, carpenter, or plumber.

This is a bipartisan idea that has been floating around for a while.

The Congressional Budget Office projected in January that, unless Congress refills its coffers, the Pell Grant program would face a $10 billion shortfall by Fiscal Year 2026.

This section of the OBBBA pours $10.5 billion into the program to plug the shortfall:

Under this section, students who are already receiving full-ride scholarships from their university won’t be eligible for Pell Grants.

This is an interesting one. It would embed what Republicans call a “do no harm” principle in federal student loans, prohibiting students from receiving loans in order to attend programs with “low earning outcomes.” Republicans argue that these are programs that leave students worse off than if they had never gone.

How will that be calculated? Essentially, undergraduate degree programs at a certain school will be ineligible for loans if, in two out of the last three years, the median earnings of the working students who graduated from the program four years before are less than the median earnings of 25-to-34-year-olds working in the state who have only a high school degree.

Generally, the state where the school is located will be used to make the comparison. But, if less than half of an institution’s students are from the institution’s state, then the median for the whole U.S. will be used.

Eligibility for graduate degree programs will operate similarly, but the comparison point will be a working 25-to-34-year-old with only a bachelor’s degree in the same state or the same field, whichever is lower. (For graduate programs that last two years or shorter, the comparison will start six years after their attendees entered the program; for graduate programs three years or longer, it will be ten years after entry.)

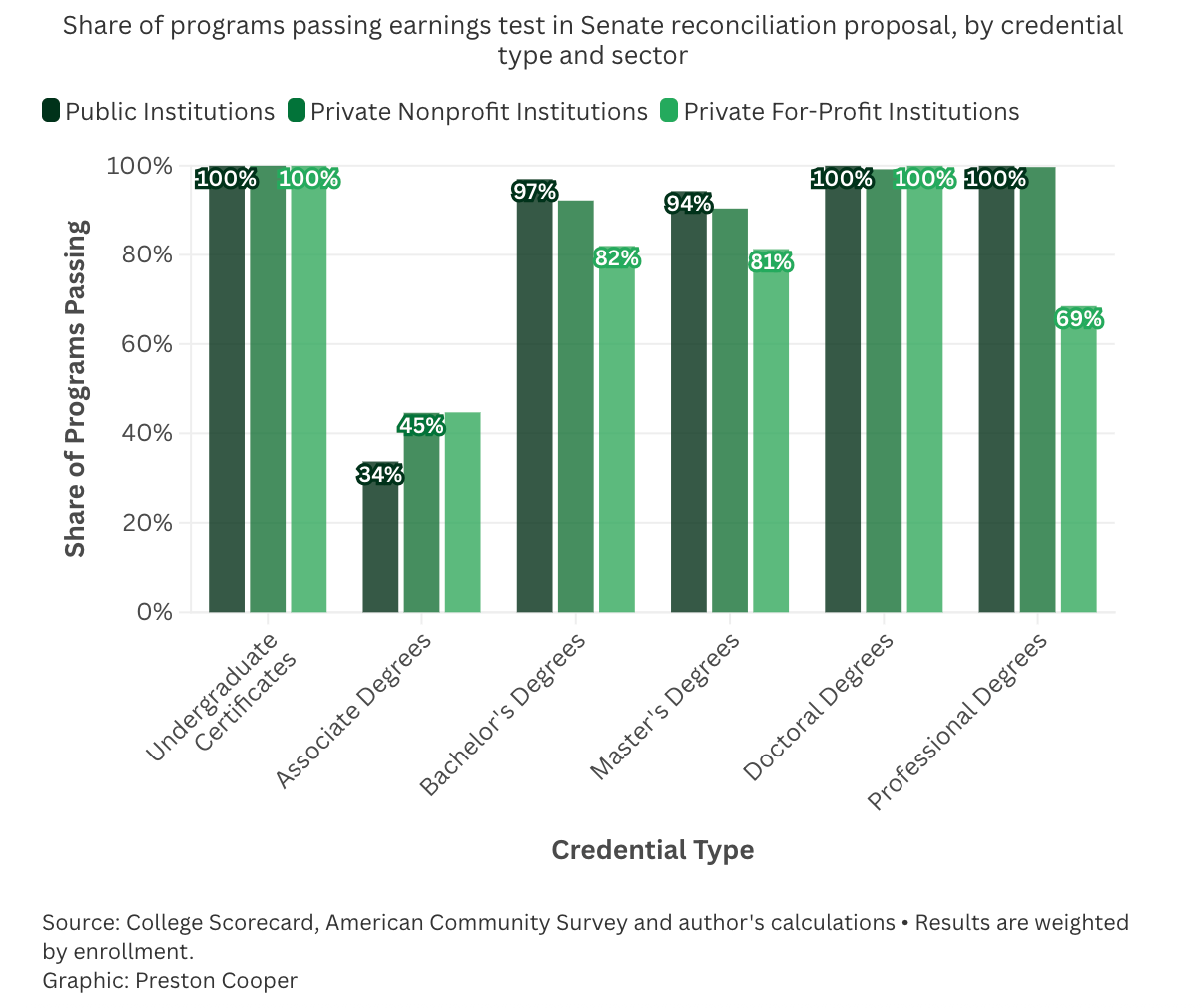

American Enterprise Institute fellow Preston Cooper found that the vast majority of bachelor’s and master’s degree programs will pass this test, but many associate degree programs will not. (However, associate degree programs are less expensive, so fewer attendees use student loans anyways.)

According to Cooper, some bachelor’s degree programs that don’t fare as well include culinary arts (only 8% of programs pass the test) and dance (29%). Unlucky master’s degree programs include alternative medicine (0%) and music (19%).

President Trump has long talked about establishing a statue garden of “American heroes.” In his first term, he listed out 244 people who would have statues in the garden: Dr. Seuss! Amelia Earhart! Kobe Bryant! Benjamin Franklin! And many others.

This section of the OBBBA appropriates $40 million to make that dream into reality.

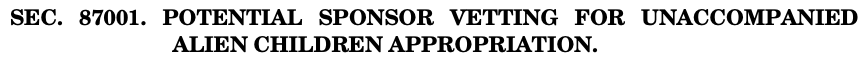

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) handless the resettlement of refugees and unaccompanied immigrant children, which is why this is in the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee title.

This section appropriates $300 million to go towards a few goals, including background checks of potential sponsors of refugees and unaccompanied children. One other funding use that caught my eye:

Title IX: Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (pp. 286-292, link)

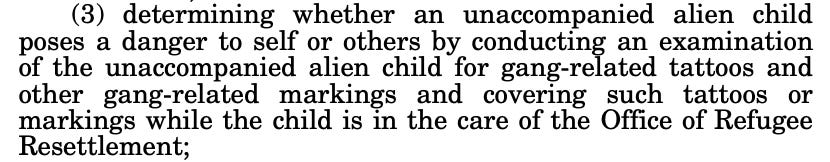

This section section appropriates $46.6 billion for these purposes:

In other words: The U.S. is building (some of) the wall.

Here we have $12 billion appropriated for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), including to hire more Border Patrol agents, offer recruitment and retention bonuses, buy more vehicles, and improve facilities and checkpoints.

Amid President Trump’s deportation campaign, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers are running out of beds and overcrowding, leading migrants to be kept in poor conditions: staying in cramped rooms, sleeping on bare floors, unable to shower for days at a time.

This section appropriates $45 billion to increase “single adult alien detention capacity and family residential center capacity”

It also includes this provision without much fanfare:

In plain English: immigrants can be kept in family residential centers for as long as it takes for them to be deported from the U.S. This might not sound like a big deal, but it would cut against the Flores settlement, a 1997 agreement in which the government said it would only hold immigrant children in detention facilities for up to 20 days. That marks a big change for how the U.S. handles migrant children; it is likely to spark legal challenges.

Here we’ve got $6.2 billion for a list of tech uses tied to border security:

The use of AI and machine learning are interesting. (I’m also curious what “commemorating efforts and events related to border security” will be.)

There’s also this interesting restriction:

The U.S. has a lot of big events coming up! This section appropriates $625 million for the federal government to reimburse state and local agencies that help with security for the 2026 FIFA World Cup, and $1 billion for agencies that help with security related to the 2028 Olympics.

The section also appropriates $10 billion to go towards state and local governments working on border security, including building fencing on the southern border or relocating “aliens who who are unlawfully present in the United States from small population centers to other domestic locations,” which seems like it could reimburse states for migrant flights.

Here’s something I didn’t know. We normally think of the Secret Service as handling presidential protection, but when state and local agencies help out securing a president’s private property in their jurisdiction, it’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) that reimburses them. This happens through a grant program known as Presidential Residence Protection Assistance.

This section appropriates $300 million for the program, which will presumably go towards reimbursing Florida police for helping secure Mar-a-Lago and New Jersey police for helping secure Bedminster, among President Trump’s other properties.

Finally, we have $10 billion more for border operations. For what specifically? It seems pretty vague to me:

Title X: Judiciary (pp. 293-330, link)

Last title, ladies and gentleman!

This one opens with a group of sections that first sets fees for immigrants applying for certain statuses, and then appropriates more funds for immigration enforcement.

Let’s start with some of the new fees imposed under the law:

$100 to apply for asylum (a status for those with a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country)

$1,000 for parole (a status based on urgent humanitarian need)

$500 for Temporary Protected Status, or TPS (a status for people from certain countries where it might be unsafe to return)

$550 to apply for employment authorization after receiving asylum, parole, or TPS, and $275 to renew it.

$250 to apply for Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status, which is for migrants who have been abused, abandoned, or neglected by a parent)

$250 for a nonimmigrant visa (which allows foreigners to visit the U.S. for work or tourism)

$1,500 for immigrants seeking a “green card” (which allows a non-citizen to live permanently in the U.S.)

$900 for appealing the decision of an immigration judge

There are also a bunch more. The amounts will increase with inflation. For the most part, the OBBBA includes language that prohibit the government from providing a waiver:

One outlier is the fee for parole status, which includes exceptions for medical emergencies and other cases:

The fee that must stuck out to me was this one:

The U.S. has a long backlog of asylum cases: more than 3 million active cases, with an average wait time of 636 days.

The above provision sets a $100 fee for each calendar year that their asylum application is still pending, effectively punishing migrants for the fact that our asylum system is so slow (presumably to incentivize them to withdraw their applications and thus reduce the backlog).

After the fees, we then $2 billion appropriated to the Department of Homeland Security, $750 million specifically to ICE, among other law enforcement expenditures.

And, now, the final provision of the law. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) is a law created in 1990 that provides payments to Americans who developed cancer or other diseases after being exposed to radiation from atomic weapons testing or uranium mining.

The authorization for RECA expired last year; the first thing the OBBBA does is extend it through 2028.

Then, it broadens eligibility for RECA compensation, to include more uranium mine workers, more people who developed diseases after being exposed to radioactive waste from the Manhattan Project, and more people exposed to fallout from atmospheric nuclear testing in Nevada in the 1950s and ’60s.

Missouri is one of the places that waste was dumped; this has been a top priority of Sen. Josh Hawley’s (R-MO) for years. It is the largest expansion of RECA since its passage.

And that’s it! Pat yourselves on the back: we made it through all 330 pages! Thanks for reading, everyone.

Thank you so much Gabe for this series. I intend to read these through more thoroughly in the coming weeks. It is unbelievable how much was stuffed into this bill. I guarantee that no single house or senate member understood what they were voting for.

These loan limitations are going to pose some serious issues for many students intending to pursue graduate degrees outside of the "professional students" category. How are they determining what is considered professional? Is it degrees that prepare students for licensure in a particular field (like clinical mental health counseling, which is often housed in schools of education)? The percentage of graduate programs that cost more than $50k/year is astounding (the vast majority of private institutions in the US, and many public institutions for out-of-state students), and these loan limitations are likely going to prevent middle and lower income students from pursuing graduate studies, which will further limit upward social mobility.

What would be far more helpful to avoid further student loan crises is updating the stupid Net Price Calculator Act, which requires every college and university receiving federal funding to have a Net Price Calculator on their website. In theory, these calculators should help families know *before applying* which schools will be affordable for them. However, the current act, which was supposedly being updated, still fails to require that the NPCs be ACCURATE, and some institutions are egregious about this oversight (like American University, who's assistant director of financial aid said publicly in a webinar last year that their NPC isn't accurate because "it doesn't have to be" (yeah, that's a direct quotation, he even typed it into the Q&A chat and I have a screenshot of it)).

Is there any world in which these things might change in the future?