Trump vs. Capitalism

Bernie Sanders 🤝 Donald Trump

Last night, the White House released perhaps its strangest press release in recent presidential history — and, friends, that is saying something.

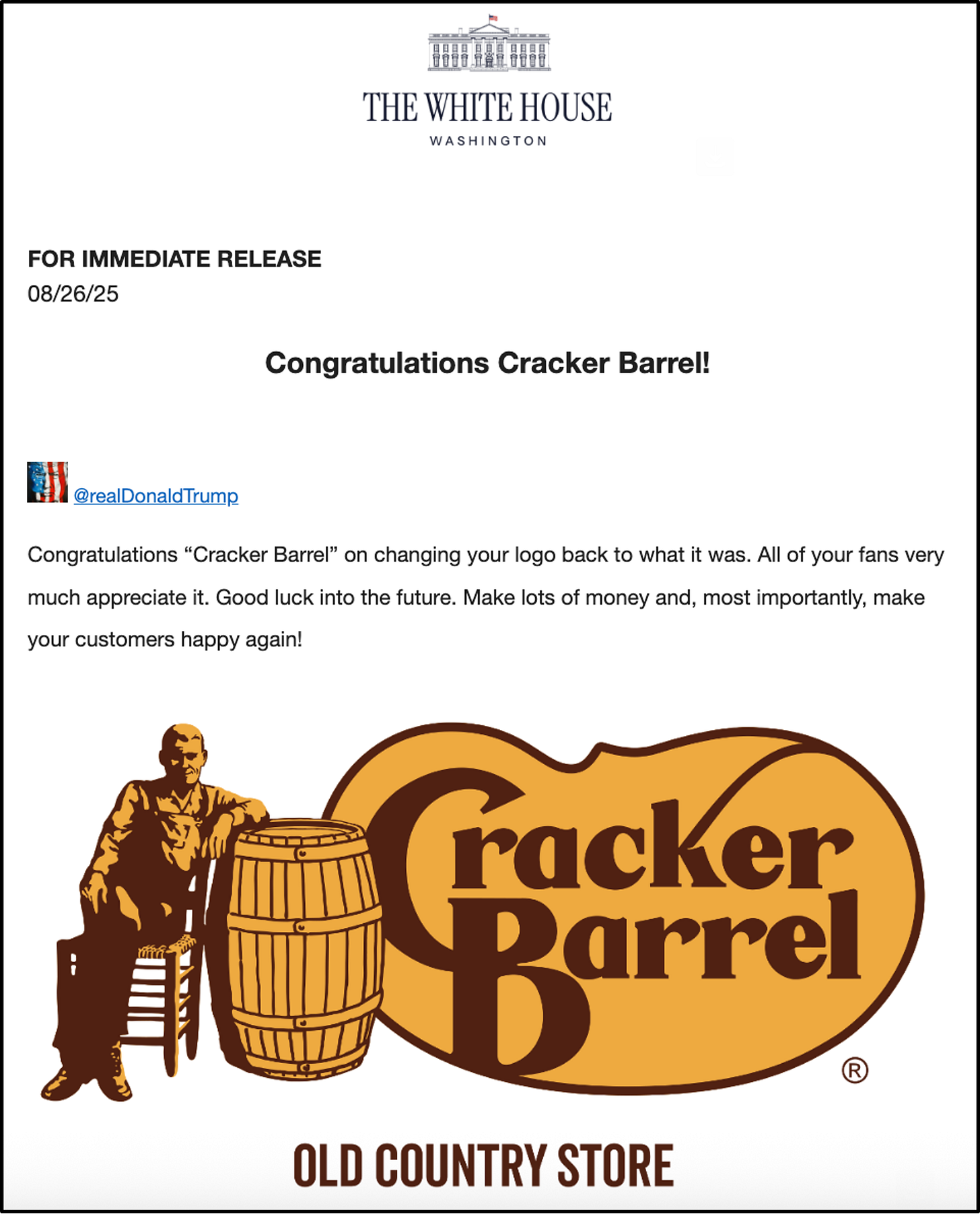

Subject line: “Congratulations Cracker Barrel!”

The email included a social media post from the restaurant chain Cracker Barrel announcing that it was scrapping its (admittedly ill-considered) new logo, as well as a post from President Trump praising the decision. The logo redesign had become a conservative cause célèbre over the previous few days, and Trump had been among the voices urging a return to the old look.

Now, the White House was dropping into reporters’ inboxes to gloat that Trump had gotten his way. “President Trump has unmatched business instincts, and an uncanny ability to understand what the American people want,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said in a statement. “Cracker Barrel is a great American company, and they made a great decision to Trust in Trump!”

Apparently, the White House involvement in this all-important issue even extended beyond emails and Truth Social posts: White House deputy chief of staff Taylor Budowich wrote last night that he had spoken on the phone with representatives from Cracker Barrel to discuss the logo controversy.

It might appear odd for the federal government to shower such attention on a seemingly minor corporate issue — but it represented only the Trump administration’s latest attempt to worm its way into the business world.

Even more consequentially than the Cracker Barrel fracas, the U.S. government has started becoming a shareholder in a string of companies: taking a 9.9% stake in Intel, in exchange for pouring $8.9 billion into the tech giant; a 15% stake in MP Materials, a rare-earth mining company, in exchange for buying $400 million in stock; and a “golden share” of U.S. Steel, which will give the government veto power over major decision by the manufacturer, in exchange for allowing the company to be acquired by a Japanese firm.

The government has taken equity in businesses before: it did so when bailing out banks and auto companies during the 2008 recession, for example. But there is virtually no precedent for the government buying shares of a company outside of a war or financial crisis, or incidents when a company was on the brink of collapse.

None of those circumstances apply here, and yet Uncle Sam will now be the largest shareholder of both Intel and MP Materials. The Trump administration has also inked a revenue-sharing deal with chipmakers Nvidia and AMD, and is floating the possibility of taking stakes in additional companies.

Lockheed Martin is “basically an arm of the U.S. government,” Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said Tuesday, by way of revealing that the Pentagon was considering taking a piece of Lockheed, Boeing, and other defense contractors. Trump has previously talked about the U.S. government assuming a 50% stake of TikTok.

“China does it every single day,” Lutnick has noted, openly drawing a comparison to America’s economic rival, which owns all or part of more than 800,000 businesses.

These partial nationalizations are, to put it lightly, a very unusual step for a Republican president to be taking.

For the last century — since the trust-busting Theodore Roosevelt left the stage and gave way to GOP presidents like Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover — a fierce devotion to capitalism and a belief in free markets has been infused into the DNA of the Republican Party.

“The United States government ought to keep from undertaking to transact business that the people themselves ought to transact,” Coolidge said in 1927, articulating a laissez-faire philosophy that would grip the GOP for the next several generations.

“It is my policy,” he added, “in so far as I can, to keep the government out of business, withdraw from that business that it is engaged in temporarily, and not to be in favor of its embarking on new enterprises.”

This way of thinking reached its zenith during the presidency of Ronald Reagan, who famously said that “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are, ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’”

Business executives probably expected Trump, the first president to go straight from the C-suite to the Oval Office, to be a natural heir to this capitalist legacy. But instead of his business experience ingraining in him the idea that there should be a wall between industry and the state, it seems like his background has made him want to merge the two — less because of any overriding economic philosophy, but because he misses having his hand in the business world, and now spies an opportunity to serve as something of a national CEO.

“On behalf of the American people, I own the store, and I set prices, and I’ll say, if you want to shop here, this is what you have to pay,” Trump said earlier this year, in the context of tariffs.

And if that doesn’t sound very capitalist, so be it: I’ve written many times before that the best to understand Trump is as someone who lacks very many consistent policy beliefs, and economics are no exception.

“Some conservatives would say, ‘That’s not free market,’” Trump acknowledged in 2016, referring to his trade policy. “I mean, we’re losing our shirts, folks. We’re losing our jobs. We don’t have a choice.”

A lot of ink has been poured in recent days debating whether Trump is a capitalist, or a socialist, or statist, or a so-called “MAGA Maoist,” or something else. More accurately, he is none of those things: his guiding principle is generally whatever idea he decides to pursue in the moment, which is what allows him to pursue nationalization of companies that interest him while pushing to privatize others (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Postal Service) that don’t; to cut taxes for the wealthy, while simultaneously browbeating CEOs into keeping their prices low even if it means reducing profits.

That said, some of Trump’s ideas do have a striking familiarity.

In fact, it was the democratic socialist Bernie Sanders who first proposed, in a failed amendment to the CHIPS and Science Act, in 2022 that semiconductor manufacturers receiving federal subsidies should be required to give equity to the government in return.

“If private companies are going to benefit from generous taxpayer subsidies, the financial gains made by these companies must be shared with the American people, not just wealthy shareholders,” Sanders said on the Senate floor, the same basic message that Trump is offering now (and referring to the same pot of money).

Meanwhile, a further dip into the congressional archives reveals a very different proposal, the Government Ownership Exit Plan Act of 2009, from one John Thune of South Dakota, which called for the government to sell off the stakes of various banks it had purchased in 2008.

“Economic competition is like sports,” Thune wrote at the time, “with teams competing against each other using agreed upon rules. The government should act as the referee, ensuring that the rules are followed and enforcing penalties when they are not. However, if the government takes an ownership stake in a company, it can no longer be expected to enforce the rules fairly, because simultaneously being a ‘player’ in the game compromises the whole system.”

“If our nation continues down this dangerous path,” he continued, “the president will be the de facto CEO of more and more segments of the economy, with Congress behaving like a 535-member board of directors. Every business decision will be viewed through an added political lens, putting even more taxpayer money in jeopardy.”

Thune, of course, is now the Senate Majority Leader. The South Dakotan has made no comment since the announcement of the Intel deal, despite Trump pursuing the exact path he warned about not so long ago. Most business leaders have remained silent as well, likely out of fear that anyone who criticizes Trump only becomes his next target.

The question that most interests me is whether Trump’s abandonment of free-market principles (when its suits him) — which Republican leaders like Thune have largely gone along with — represent a permanent pivot in economic policy for the GOP, or more of a temporary aberration.

The answer will likely depend on whether Trump’s efforts to take more control of the economy — including his steps to assert dominance over the Federal Reserve — prove to be a financial success. One Republican parallel is Richard Nixon, who began his political career as a staunch anti-Communist but eventually imposed temporary wage and price controls as a way to stem inflation. (The conservative economist Milton Friedman would later call Nixon “the most socialist of the presidents of the United States in the 20th century.”)

The experiment was initially popular, but the “Nixon shock” proved disastrous, both politically and econimically. That opened a philosophical vacuum in the GOP; ultimately, Reagan would win the subsequent factional battle, urging his fellow Republicans to double down on fiscal conservatism, setting the party on the path it pursued … until Trump came along.

For the moment, Republicans who came of age politically in the Reagan era, like Thune, are on the backfoot, replaced by Trump-era Republicans like JD Vance who are plotting a much more populist course. As with the end of the Nixon administration, which side ultimately takes power after Trump will likely hinge on the state of the economy come 2028.

I am a big fan of sunset clauses and exit plans. They force reevaluations at set times. I think that any legislation that the Supreme Court calls “major questions” should be subject to sunset/exit clauses. The lack of lets the Congress sit out controversies and blame the other party instead of keeping an eye on what is working and what is not.

I question the use of the term “partial nationalization” without a specific definition relating to control issues.

I go back and forth on this. On the one hand, we (through the government) spend a LOT of money "helping" many companies and industries (I use quotes intentionally because I'm not sure the money helps, hurts, or both, depending). It does feel like we should get some of that money back, especially given the size of the debt. On the other hand, maybe the real answer is to not spend that money and actually let the free market work the way it's supposed to--creative destruction, it's called. Yeah, jobs are lost in the short term (the biggest argument against capitalism); they are also created at the same time. On the whole, I come down on the side of capitalism.

If Trump were actually interested in paying down the debt, I'd be all for it. But so far he's shown no signs (other than words) that he'll do that. Like every other politician before him, regardless of what party they belong to or what philosophy they profess to adhere to, he is more interested in spending any additional revenue to pay for more goodies "for the people" (and himself, like every other politician before him) than bringing down the debt.

If you've never read "Parliament of Whores" by P.J. O'Rourke, you need to. It's a little out of date in terms of the characters and numbers, but it's entirely up-to-date in reporting how government really works.