Trump’s Month of Grabbing Power

Can he fire a Fed governor? No one knows, and we’re about to find out.

The animating goal of Donald Trump’s second term has been to remake American government in his image.

But even by that standard, August stands out as a period where he has moved to aggressively centralize his power, grabbing a series of third rails that previous presidents have often shied away from.

Consider a sample of Trump’s actions from this month, when he’s had Washington to himself, with the other two branches of government on recess:

Fired the official in charge of collecting the country’s employment statistics after the release of an unflattering jobs report.

Pushed states to redraw political districts in his favor outside of the normal timeline.

Deployed troops to patrol the nation’s capital city, and mused about sending them to other major cities.

Called for a top critic to be prosecuted, days after another top critic’s home and office was raided by federal agents.

Repeatedly insisted he should win a Nobel Prize, after convening flashy meetings with the leaders of Russia and Ukraine.

Led the government in taking a 10% stake in a major company.

Joked about canceling the next election and declared his intention to lead a “movement” to revamp voting laws.

Conducted a purge of national security officials, including removing the head of an intelligence agency that had recently contradicted him.

Urged federal regulators to revoke the broadcast licenses of TV networks whose coverage he doesn’t like.

Asserted control over the country’s cultural institutions and museums, in an attempt to remove content he disagrees with, while also giving his office a gilded makeover.

It’s worth taking a moment to consider how we would read that list if it were describing the leader of a foreign country. Many of these actions are seen as classic characteristics of a banana republic.

Here’s another: meddling with the independence of a country’s central bank. Last night, as if to cap off his month of trampling guardrails, Trump checked that off his list as well, when he announced the firing of Lisa Cook, one of the 13 governors of the Federal Reserve.

Like many of his other August actions, the removal comes with little precedent in U.S. history: no president has ever tried to fire a Fed governor. To an even larger extent than most of the others on the list, the move is of dubious legality and carries enormous consequence. It is also likely to spark showdowns between Trump and perhaps the only two men in Washington who boast greater power than his own: John Roberts and Jay Powell.

Let’s take them one at a time.

First, a look at the legal stakes.

Federal Reserve governors — who oversee America’s central bank and monetary policy, including by setting interest rates — serve for 14-year terms. Cook, a Biden appointee, started her current term in February 2024, which means she normally would have had the option to serve until 2038.

Instead, Trump sent her a letter yesterday asserting that her time on the Fed board was over, effective immediately.

Trump cited the Federal Reserve Act, codified at 12 U.S.C. § 242, which allows the president to prematurely remove a Fed governor “for cause.” Trump wrote Cook that he had “determined that there is sufficient cause to remove you from your position” based on a criminal referral sent to the Justice Department last week by Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Director Bill Pulte, who accused Cook of committing mortgage fraud.

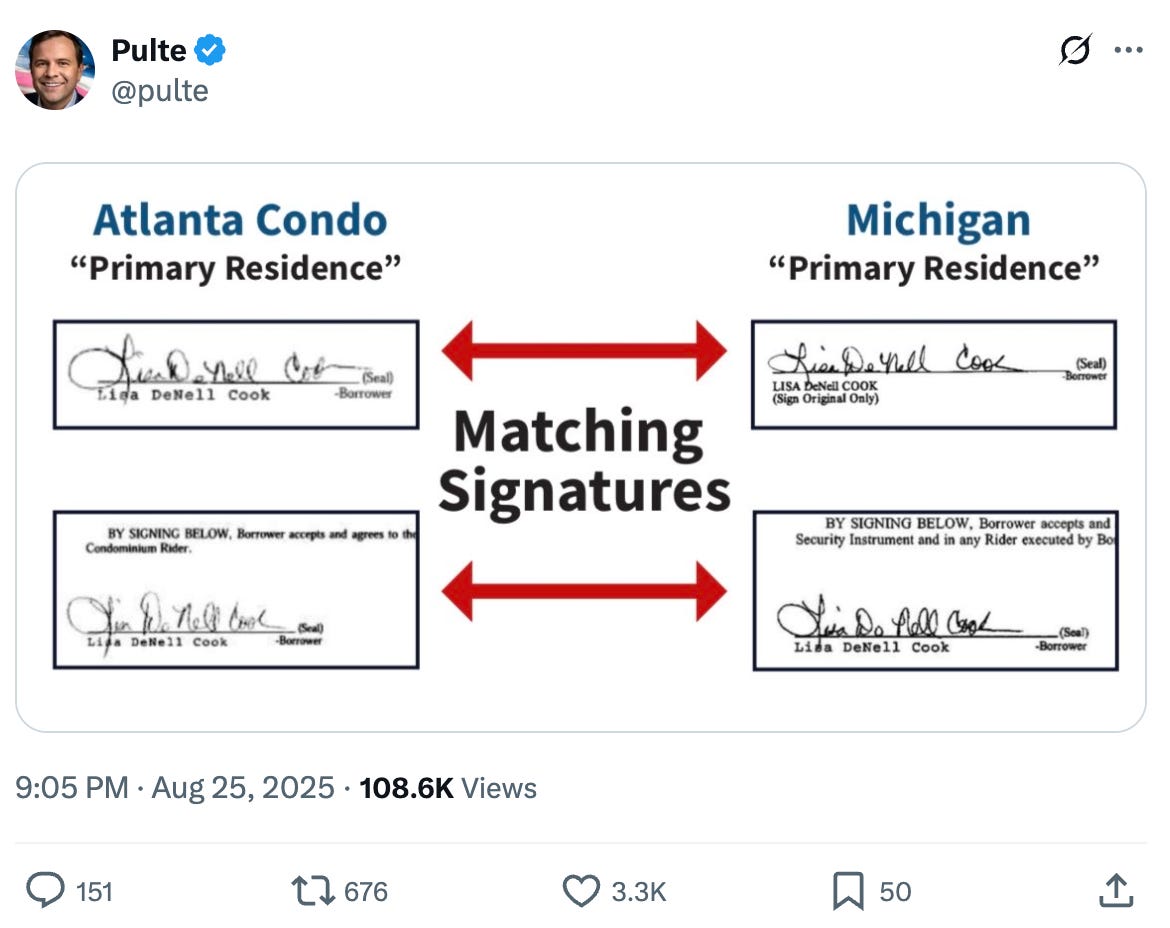

Pulte, a top Republican donor who has also leveled similar accusations against other Trump rivals, alleged that Cook entered into two mortgage agreements over a two-week period in summer 2021, claiming both properties (one in Michigan and one in Georgia) as her “primary” or “principal” residence.

Borrowers often receive more favorable mortgage rates for a property claimed as their primary residence. It is illegal to lie on a loan application.

Notably, Cook said last week that she is “gathering the accurate information to answer any legitimate questions and provide the facts,” but has yet to provide any evidence rebutting Pulte’s claims. At the same time, she has not been criminally charged by the Justice Department.

Under the Federal Reserve Act, is it enough for the president to merely state that “cause” exists when firing a Fed governor, even if it’s something the official hasn’t been found guilty of?

No president has ever tried, so there’s no established answer to that question.

Cook said last night that she believes the answer is “no”; until proven otherwise, she plans to continue serving in her position.

“President Trump purported to fire me ‘for cause’ when no cause exists under the law, and he has no authority to do so,” she said in a statement. “I will not resign. I will continue to carry out my duties to help the American economy as I have been doing since 2022.”

Cook has retained the services of Abbe Lowell, a Washington superlawyer who has represented everyone from Ivanka Trump to Hunter Biden. “We will take whatever actions are needed to prevent his attempted illegal action,” Lowell said last night.

Presumably, she will file a lawsuit and ask a judge for a temporary restraining order stating that she can remain on the Fed board while the legal challenge works its way through the courts. The case is almost certain to eventually reach the Supreme Court.

The irony here is that the Supreme Court has been incredibly accommodating of Trump’s efforts to fire federal officials thus far — but they’ve appeared to carve out one exception: the Federal Reserve.

Over a series of cases on its so-called “shadow docket” this year, the conservative majority on the court has repeatedly chipped away at Humphrey’s Executor, a landmark 1935 precedent that limited the president’s ability to fire officials at independent agencies.

This would seem to set a precedent that would allow firings at the Fed, too, except for this one line the justices included in a May order: “The Federal Reserve is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States,” the court wrote, suggesting that the central bank belonged to a category of its own.

The justices offered no further legal justification for placing the Fed in its own bucket, making it seem like a fairly transparent play to get rid of Humphrey’s Executor while avoiding arguably the largest consequence of doing so (the potential threat to central bank independence).

In the short term, this confusing legal state of play — the Supreme Court has kind of overturned the precedent that might have blocked Trump’s action (without formally doing so), but it also kind of carved out the Fed (without really explaining why) — puts the district judge who will receive the case in a bind.

Just last month, the Supreme Court suggested that its rulings chipping away at Humphrey’s should be treated as quasi-precedent for lower courts (despite the fact that those rulings have taken the form of brief, provisional orders that offer little, if any, legal explanation). The judge in Cook’s dispute will have to decide if the Supremes also mean for this to be the case when a firing involves the one agency that the justices have vaguely hinted they still want preserved from presidential prerogative.

In the long term, Trump is calling the Supreme Court’s bluff. Chief Justice John Roberts and his colleagues have indicated that they are willing to let Trump fire whoever he wants, just with this one potential exception. Now Trump is after that one exception: he is going to force the court to either give him his way, or come up with a tortured reason why he can fire all but seven people in the federal government.

The second major standoff this creates is with those seven people, especially Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

Again, there is a fascinating short-term dilemma here. Trump says that Cook is no longer a Fed governor. Cook says that she is. Powell will have to take a side. On September 16, the Fed will meet for the next time to cut interest rates: either Powell will include Cook at the table or he won’t. (Presumably, a federal judge will decide for him by then, but how Powell handles the situation in the interim — and whether he chooses to openly vouch for Cook, either at that meeting or before — will be a major decision point.)

But the long-term implications are even larger. Trump has been threatening for months now to tear away at the metaphorical wall between the White House and the Federal Reserve. Initially, it seemed like that might mean firing Powell. Perhaps coming up short with a justification for that removal (he seemed to consider using the Fed’s renovation as a pretense), Trump is now testing the waters by trying to axe Cook instead.

If he proves successful, Trump would have four appointees on the seven-person Fed board: two from his first term, one to succeed Adriana Kugler (who unexpectedly resigned this month), and one to succeed Cook.

That would be a powerful bloc of votes to achieve Trump’s goal of cutting interest rates, which the Fed has so far refrained from doing. (Interest rates are set by the Federal Open Market Committee, which is made up of the seven Fed board members and five regional Fed bank presidents.)

It would also put the rest of the board, including Powell, on notice, since Trump would have received the legal sign-off he seeks to be able to fire Fed governors basically at will. The Fed’s hard-built independence, which has been a bedrock source of stability for the U.S. financial system, would evaporate. Interest rates would then be, more or less, in the hands of each successive president, who could remake the Fed board at a whim unless their preferred monetary policy is adopted.

For now, though, this is all an “if.” The Supreme Court has already hinted at a willingness to protect the Fed from presidential intervention. Now Trump is forcing the justices to either say that explicitly (and make their highest-profile break with him so far) or add the central bank to the list of institutions — from Washington, D.C. to Intel — that he has spent August placing firmly within his power.

The Supreme Court has made a huge error in undoing Humphrey's Executor, both in legal and practical reasoning. Legally, the Constitution vests Congress with the ability to make laws to determine how our country will be run. In many cases, they have created agencies, bureaus, commissions, and other government institutions and have specified how leadership gets appointed and how they can be fired. The President's job is to faithfully execute the laws that Congress has passed, not to change the rules simply because he is inconvenienced by them.

Practically, these independent agencies are made independent of larger departments for a reason. It could be to streamline their operation, focus their attention, or isolate them from the political winds. The Fed, CFPB, USAID, and others were intended by Congress to be free of partisan politics because Congress and the President who signed those laws knew that politicians could not be trusted to leave them alone.

If the Courts allow Trump to fire Cook, it will create economic havoc as investors will lose all confidence in the markets. Hopefully, the Supremes will value their investments more than they appear to value democracy and the Constitution.

Well presented. In other words, I could follow it and it made sense to me. But why is the Supreme Court so reluctant to flatly oppose Trump’s moves for complete autocratic control?