Trump Has Withdrawn a Record Number of Nominees This Year

The reasons are mixed, but some — like Paul Ingrassia — reflect subtle GOP pushback.

In the first week of the second Trump administration, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth was confirmed despite allegations of sexual assault, excessive drinking, and financial mismanagement. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was approved as Secretary of Health and Human Services despite senators expressing concerns about his inflammatory comments on vaccines.

Even more recently, the Senate has signed off on Herschel Walker’s nomination to be ambassador to the Bahamas (even though two women have accused him of domestic abuse) and Joe Kent’s nomination to lead the National Counterterrorism Center (despite his links to the Proud Boys and other far-right groups).

It would be fair for a casual observer to question whether there were any Trump nominees that the Republican-controlled Senate would not be willing to green-light. Indeed, not a single Trump nominee has been voted down since he returned to office.

That’s a misleading statistic, though. Presidential nominees are rarely rejected by the Senate outright: the last failed Cabinet-level confirmation vote was in 1989, when George H.W. Bush tried to install John Tower as Defense Secretary. (Tower, like Hegseth, faced allegations of alcohol abuse and pledged to quit drinking if confirmed.)

Instead of suffering the humiliation of a failed floor vote, presidents will generally withdraw nominees when it becomes clear they lack the votes to be confirmed. This is a better metric of how many presidential nominees have been overwhelmed by opposition in the Senate — and if you look at Trump’s withdrawal count, suddenly his record of bashing the Senate into submission doesn’t look so sterling.

Even before he took office, Trump’s first pick for Attorney General, Matt Gaetz, was forced to withdraw after it became clear that Republican senators were not willing to overlook allegations that Gaetz, as a congressman, paid to have sex with a 17-year-old. In May, Trump pulled his nomination of Ed Martin to be the U.S. Attorney in Washington, D.C., after Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) drew the line at Martin’s defense of January 6th rioters.

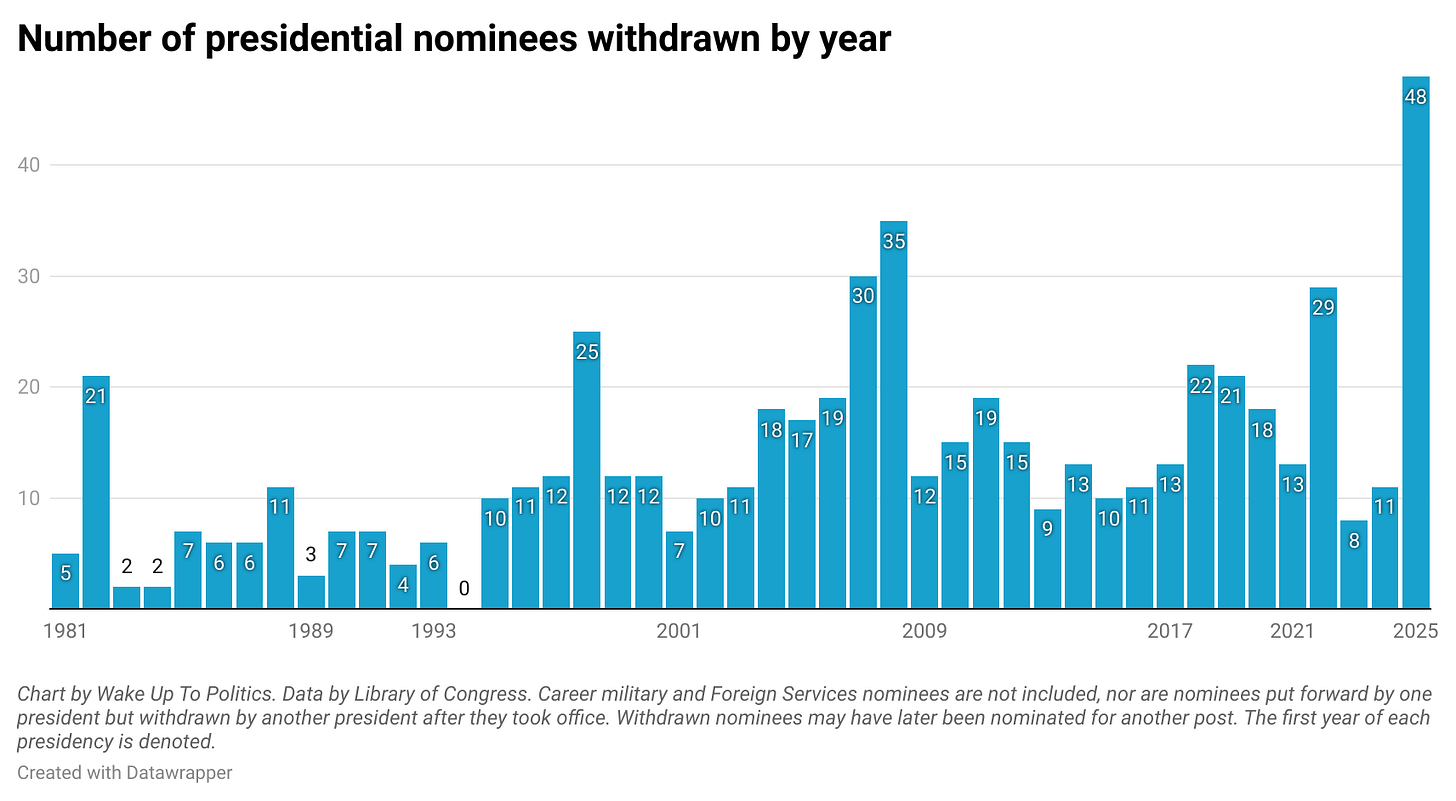

In total, according to a Wake Up To Politics analysis going back to the Reagan era, not only has Trump had to withdraw more nominees than any recent president in their first year in office — none have withdrawn as many nominees in their first two years as Trump has in his first.

No single year, at least since 1981, has seen a president withdraw as many nominees as Trump has in 2025 … and there are still two months left for Trump to keep running up that record.

Trump’s 49th withdrawal of his second term appears to be only days away: Politico reported on Monday that Paul Ingrassia, the president’s pick to lead the Office of Special Counsel,1 texted in a group chat with other Republican operatives last year that has “a Nazi streak,” that his colleagues should “never trust a chinaman or Indian,” and that “MLK Jr. was the 1960s George Floyd and his ‘holiday’ should be ended and tossed into the seventh circle of hell where it belongs.’”

In another string of texts, Ingrassia said that there should be “no moulignon holidays,” using an Italian slur for Black people, “from kwanza to mlk jr day to black history month to Juneteenth.” At another point, he wrote: “We need competent white men in positions of leadership. … The founding fathers were wrong that all men are created equal … We need to reject that part of our heritage.”

Ingrassia, who has ties to far-right figures and has been accused of sexual harrasment2, was slated to appear before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee for a confirmation hearing on Thursday — but it’s now unclear whether the session will take place at all.

At least three Republican members of the panel — Sens. James Lankford (R-OK), Rick Scott (R-FL), and Ron Johnson (R-WI), all rock-ribbed conservatives — told reporters Monday that they oppose Ingrassia’s nomination, which would be enough to sink him in committee.

“I think so,” Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) said Monday when asked whether the White House should pull the nomination. “He’s not going to pass,” Thune added.3 If the Gaetz and Martin examples are any guide, now that it is clear Ingrassia lacks the votes to be confirmed, Trump will likely withdraw his nomination.

To be clear, not all of Trump’s withdrawn nominees have been due to Senate opposition: the reasons are more mixed than that. A striking number have been pulled due to intra-MAGA spats, including Chad Chronister (DEA), Jared Isaacman (NASA)4, Brian Quintenz (CFTC), Janette Nesheiwat (Surgeon General), and Penny Schwinn (Deputy Education Secretary). Circumstances intervened in some cases, like Trump pulling Elise Stefanik’s candidacy to be UN Ambassador after Republicans could no longer afford to lose her House seat. And some withdrawn candidates were later switched to other roles, like the conservative activist L. Brent Bozell III, who went from being nominated to lead the U.S. Agency for Global Media to being Trump’s pick to represent the U.S. in South Africa.

Other nominees followed the Gaetz/Martin route: being pulled after they were engulfed in confirmation-dooming controversy. Would-be CDC Director David Weldon was withdrawn after Sens. Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Susan Collins (R-ME) told the White House they would oppose him due to past comments linking vaccines to autism. Trump’s pick to serve as Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Afairs, Adam Boehler, was yanked in March after Senate Republicans expressed outrage that he took the unprecedented step of negotiating directly over hostages with officials from Hamas. (A new post — Special Envoy for Hostage Response — was later created for Boehler that didn’t require Senate confirmation. Trump did the same thing for Martin.)

More recently, Trump withdrew E.J. Antoni, his controversial nominee to lead the Bureau of Labor Statistics, last month after CNN reported on his “since-deleted Twitter account that featured sexually degrading attacks on Kamala Harris, derogatory remarks about gay people, conspiracy theories, and crude insults aimed at critics of President Donald Trump.”

The Antoni case is especially interesting, since not a single Republican senator had publicly announced opposition to his nomination. But clearly there were GOP lawmakers that signaled their distaste privately, and enough of them that Trump read the tea leaves and backed down. Antoni’s withdrawal (apparently purposefully timed for the eve of the shutdown) generated far fewer headlines than his nomination — and certainly fewer than a more extended public fight over the nomination would have.

This is one example of how the withdrawal list reveals more subtle Republican backlash to (some) Trump picks than even many in Washington are aware of: while the controversial successful confirmations draw attention, the quiet surrenders are shrouded in secrecy. Oftentimes, GOP senators are careful not to go public with their concerns, which means nominees are sometimes withdrawn without the media even realizing there’s a problem. (The fact that he has set the withdrawals record had also not been previously reported.)

In one case, North Carolina attorney Charlton Allen appears to have been tapped to lead the Office of Special Counsel (the same position Ingrassia is now up for), only for his bid to be pulled six days later, without a single news article on either his nomination or withdrawal. The reasons behind the move are unclear; Allen would later be nominated for a different post (General Counsel of the Federal Labor Relations Authority) four months later.

Similarly, no explanation has been offered for why Mark Brnovich’s nomination was withdrawn to be U.S. ambassador to Serbia5 or behind Theodore Cooke’s aborted nomination to head the Bureau of Reclamation. In both cases, there are hazy signs of dissent: Cooke has suggested that Republican senators from states like Utah felt he would favor his native Arizona in negotiations over the Colorado River; Brnovich said “it became clear that the bureaucracy of the ‘deep state’ does not want to serve anyone with my political, ethnic and religious background in Serbia.”

Brnovich did not identify his “deep state” adversaries, or clarify whether they were Democrats or Republicans.

Still more withdrawals appear to stem from nominees refusing to carry out Trump administration orders: at least two U.S. attorney picks — Todd Gilbert and Erik Siebert — were reportedly withdrawn as nominees to hold their posts permanently after they raised concerns about investigating Trump critics while serving as prosecutors temporarily. (If you recognize Gilbert’s name from the news, it’s probably for a very different reason: he is the former GOP state legislator who Virginia Democratic attorney general nominee Jay Jones mused about killing in recently released text messages.)

Taken together, some of the withdrawals do appear to show that Republican senators have red lines when it comes to Trump nominees — however faint they may be: identifying as a Nazi, representing Capitol rioters, (allegedly) having sex with a minor, meeting with Hamas, taking sides in a water dispute. While Republicans have generally endorsed even Trump’s more controversial nominees, by the metric of withdrawals, he has suffered markedly more personnel setbacks than any of his predecessors.

The withdrawals also show that the haphazard nature of Trump’s first term has carried over to his second: many of these picks never even would have been named in prior administrations, because the White House wouldn’t have gone through the trouble of nominating them without making sure they would receive sufficient Senate support.

Instead, the Trump team appears often to be vetting on the fly, with damaging information being surfaced after nominations are announced, rather than before.

You can read this in one (or both) of two ways. Perhaps it shows a White House that’s unprepared, getting into avoidable fights because it isn’t doing the legwork ahead of time. Or maybe it shows a White House that’s unleashed, knowing it will lose some battles in Congress but — after having won so many — seeing little point in not at least trying, knowing there’s always a chance that the weakened Republican caucus could be cowed into not putting up a fight.

The GOP’s recent Senate rules change allowing large batches of nominees to be confirmed by majority vote will also help in this regard: that’s how some controversial nominees like Walker or Kent have been confirmed, enmeshed in the safety of a crowd.

This strategy of heightened peer pressure and hiding controversial nominees in large groupings has generally been a success for Trump, although his unprecedented spate of withdrawals also reveals the times that Republicans — away from the spotlight — have quietly decided that he’s pushed too far.

The Office of Special Counsel is an independent agency designed to protect the apolitical nature of the civil service, including by enforcing the Hatch Act (the statute preventing agencies from carrying out partisan activities, which the Trump administration has been accused of violating during the shutdown) and by protecting whistleblowers.

It is different than the Office of Special Counsel that is sometimes stood up within the Justice Department when the Attorney General decides that a prosecutor needs a special level of independence to carry out a sensitive investigation — like when Robert Mueller was appointed as Special Counsel to investigate Trump during his first administration, or when Jack Smith held the title to investigate Trump during the Biden era.

The Muller/Smith type of Special Counsel is temporary; the Office of Special Counsel that Ingrassia was appointed to lead is a permanent agency with an ongoing mandate.

According to Politico: in late July, while traveling for work in his current capacity as White House liaison for the Department of Homeland Security, Ingrassia arrived at a Ritz-Carlton in Orlando with a lower-ranking female colleague and other employees.

“When the group reached the front desk, the woman learned she didn’t have a hotel room,” Politico reported. “Ingrassia then informed her that she would be staying with him, according to five administration officials familiar with the episode. Eventually the woman discovered that Ingrassia had arranged ahead of time to have her hotel room canceled so she would have to stay with him, three of those officials said.”

“The woman, a fellow Trump appointee, initially protested the room arrangement. But, not wanting to cause more of a scene around other colleagues, she relented, according to the officials. So the two, who knew each other previously as friends, went to the room and slept in separate beds. Ingrassia’s attorney said no last-minute changes were made to the hotel reservations.”

“What’s not disputed is that the two ended up sharing a room on the business trip, and that it resulted in an official investigation.” (The woman filed a human resources complaint, but reportedly retracted it due to fear of retaliation — ironically, the type of thing the permanent Office of Special Counsel exists to prevent. The DHS inspector general appears to still be moving forward with an investigation into Ingrassia.)

This is only the latest subtle break between Trump and Thune, who has been careful to remain allegiant to the president since becoming Senate Majority Leader — but has also raised concerns about many more Trump decisions than House Speaker Mike Johnson. Tariffs, FCC/Kimmel, and shutdown layoffs are other examples.

Isaacman is reportedly now back in the running to lead NASA again, sparking an “ugly” power struggle with Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy.

Brnovich, the former attorney general of Arizona, is the namesake of Brnovich v. DNC, a Supreme Court case that helped unwind part of the Voting Rights Act.

Gabe, unrelated question for this week from me: is the VP’s prominence in trips, press conferences, etc. because the Trump White House assumes he’ll succeed Trump as president or because Trump is so busy redesigning the White House, or a different reason?

A well-functioning Dem part would not have voted for any Trumplican nominee ever. And going forward, we should be at war with the nutless deplorable party of the Trump Cabal.

And, win both houses in 2026. We should be in a position before 2028 to impeach TRUMP and negligent dunce cabinet.