This is How Shutdowns Always End

It’s never the leverage that minority parties imagine.

Let’s begin today by reviewing some history.

Since government shutdowns were invented by an attorney general’s memo in 1980, there have been eight of them that have lasted more than a single day.

In 1981, Ronald Reagan sparked a two-day shutdown by vetoing a funding measure that didn’t include his desired $13 billion in spending cuts and $3 billion in tax increases. He ultimately received only $4 billion in spending cuts and no tax increases.

In 1990, the government shut down for three days after House Minority Whip Newt Gingrich led a revolt of House Republicans against a funding deal agreed to by George H. W. Bush that violated Bush’s “no new taxes” pledge. The intra-GOP split only gave Democrats more leverage, and not only did the final deal still raise taxes: it added an income tax increase, which had been what Gingrich wanted least.

In late 1995 and early 1996, the government shut down twice, for five and 21 days, respectively, when Gingrich — by now speaker of the House — insisted that Bill Clinton submit a plan that congressional scorekeepers affirmed would balance the budget in seven years. Clinton ultimately did offer such a plan, but it was non-binding, and Republicans didn’t even end up liking it. Once again, the shutdowns were seen as giving Democrats leverage; the final spending agreement for that year did not include a seven-year balanced budget plan and actually ended up undoing $5 billion in spending cuts that Gingrich had previously won.

In 2013, Ted Cruz led Republicans into a 16-day shutdown, demanding the repeal or at least delay of the Affordable Care Act. Obamacare was not repealed or paused; all Republicans won was a minor change to the program, requiring the Obama administration to more carefully check the incomes of people signing up for subsidies under the law.

At the beginning of 2018, Democrats forced a three-day shutdown to demand protections for “Dreamers,” immigrants who arrived in the U.S. illegally as minors. All they received was the promise of a vote on a bill to do that. The Senate ended up holding four such votes; all of them failed.

At the end of 2018, into the beginning of 2019, Donald Trump sparked a 35-day shutdown over his demand for $5.7 billion in border wall funding. He ended up receiving $1.4 billion for steel fencing (but nothing for a concrete wall), although he later declared a national emergency to try to fund the wall himself.

That brings us to the 8th multi-day shutdown in U.S. history, which is now circling towards a resolution. At 41 days and counting, the current shutdown has lasted longer than any of the previous seven — but it will end in exactly the same way. Like their predecessors, the party that forced the funding gap (here, the Democrats) laid out a long list of ambitious demands: a permanent extension of enhanced Obamacare subsidies; a rollback of the Medicaid cuts approved by Republicans earlier this year; a restoration of funding for public broadcasting; and limits on the president’s ability to tamper with federal spending.

And like every previous shutdown-forcing party, the Democrats will receive none of that, walking away with only paltry concessions: a pledge by Senate Republicans to hold a vote on a Democratic bill extending Obamacare subsidies by the second week of December (with no guarantee that the bill will pass or receive a vote in the House), and a return to how things were before the shutdown (that is, a reversal of mass layoffs carried out by the Trump administration during the shutdown and a provision to provide backpay to federal workers who missed paychecks during the shutdown, something that had already been widely understood to be required under a previous law).

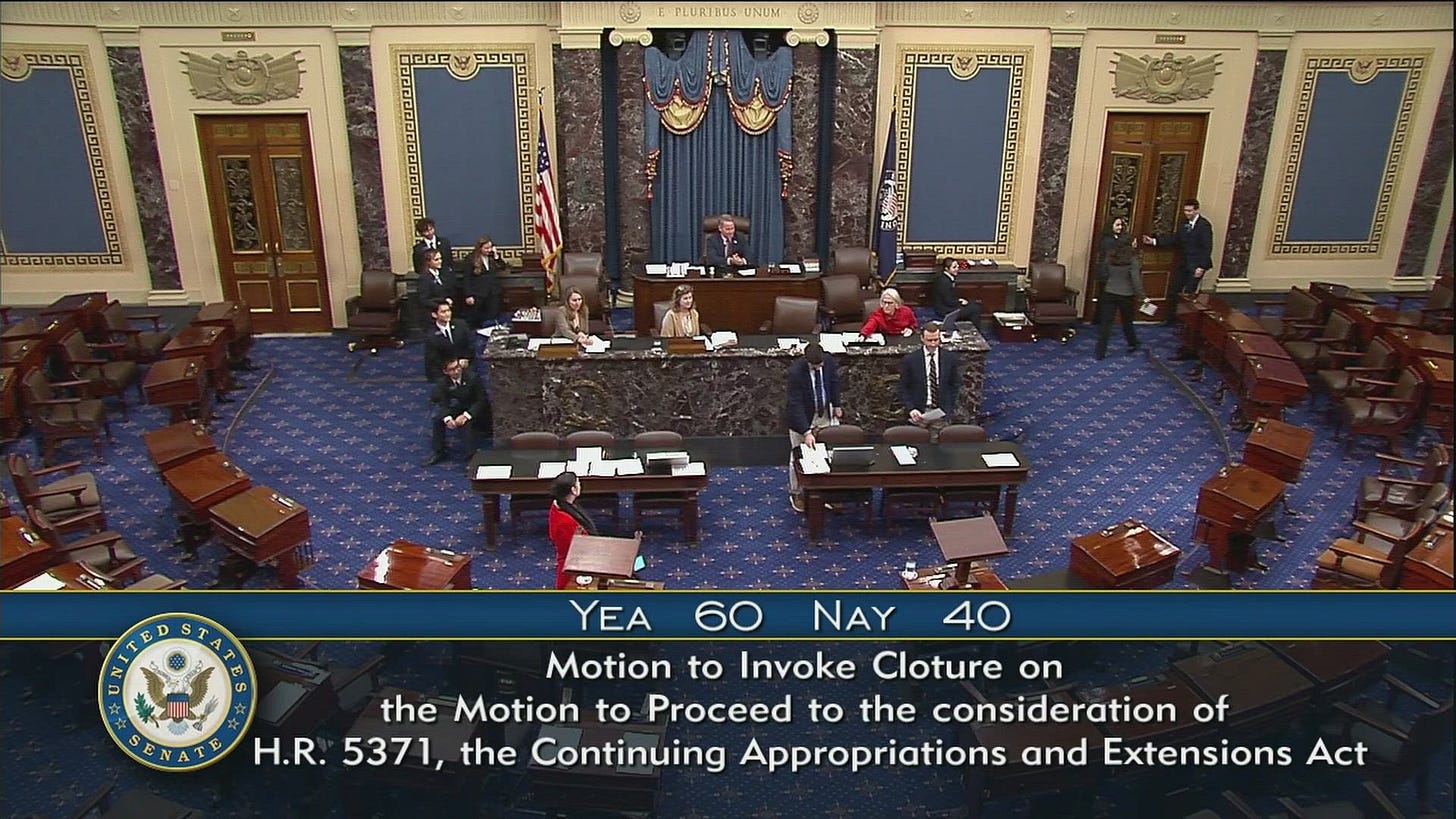

The Senate voted 60-40 — without a single vote to spare — to advance a deal along those lines last night. New Hampshire’s two Democratic senators, Maggie Hassan and Jeanne Shaheen, and Maine Sen. Angus King, an Independent who caucuses with the Democrats, brokered the agreement. Five other Democrats — Catherine Cortez Masto (NV), Dick Durbin (IL), John Fetterman (PA), Tim Kaine (VA), and Jacky Rosen (NV) — voted for the compromise. One Republican, Rand Paul (KY), voted against it.

The deal will fund the government through January 30, while also fully funding the Legislative Branch, Agriculture/Rural Development/Food and Drug Administration, and Military Construction/Veterans Affairs appropriations bills through the end of the fiscal year in September. Notably, the Legislative Branch bill staves off cuts to the Government Accountability Office — a Trump bête noire — that House Republicans had sought, and does not include proposed GOP language preventing the GAO from suing the Trump administration over withholding federal funding. (An appeals court ruled in August that the Impoundment Control Act of 1974, which prevents presidents from refusing to spend federal funds, can only be enforced through a lawsuit by the GAO.)

The package now needs to receive final approval in the Senate, which could take several days depending on how obstinate Paul and the 45 dissenting Democrats choose to be. (Paul is upset about language in the Agriculture bill cracking down on the hemp industry.) The measure will then head to the House, and then to President Trump’s desk for his signature.

If shutdowns always end in this same anticlimactic manner, why did Democrats ever expect anything different?

Two words: Donald Trump. We’ve known since the beginning of the shutdown that House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) and Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) were opposed to any extension of the enhanced Obamacare premium tax credits (which eventually became the main Democratic demand during the funding fight).

The basic Democratic hope here was that they would be able to convince Trump to split from his two legislative deputies and strike a deal with Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) on health care.

And to be clear: this was unlikely, but it wasn’t impossible. We know Trump has a streak within him that likes the idea of doing big bipartisan deals (although it’s been buried deep, deep within him since around 2019). And we also know that Trump is more politically savvy (and less ideologically stringent) than Thune or Johnson: just as he has moderated his party’s position on abortion and Medicare and Social Security cuts out of fear of being punished by voters, it wasn’t insane to think that Trump might see the very lopsided polling in favor of Obamacare subsides and tell Republicans to screw their principles and strike a deal.

In fact, this almost happened a few times during the shutdown. But each time, Thune and Johnson wrangled Trump in line and got him back on message: no health care talks until the government reopens. (We often think of Trump keeping Thune and Johnson on a tight leash, but this was an example of the reverse.) It’s been clear for some time now that Republicans weren’t going to agree to a health care deal with a gun to their head.

One part of the Democratic strategy did work: the public blamed Trump for the shutdown more than they blamed Democrats, and that did spook Trump politically. But he responded to those polls not by embracing the Democratic plan (negotiating on subsidies), but by proposing an idea of his own: Republicans eliminating the filibuster.

However, just as there was not 60 votes in the Senate for the Democratic plan to end the shutdown, there was also not 51 votes in the Senate for the Trump plan.

Therefore, there was really only way this would end, the same way every government shutdown has ended (and, immodestly I would add, the same way I said the shutdown would end before it even began): with Democrats allowing the government to reopen in exchange for a vote on Obamacare and other small concessions.

It’s true that the shutdown was going better for Democrats politically than many (myself included) expected, but with Trump unwilling to strike a deal (and, by all appearances, in no particular rush to end the shutdown), that made no fundamental difference in the underlying policy outlook. Democrats made the same mistake that was made in all seven of the previous funding gaps: imagining that a shutdown would provide more leverage than it actually would.

As AEI’s Jay Cost wrote yesterday, “The filibuster is a brake, not a gas pedal.” It is an effective tool to block a piece of legislation (like a government funding bill, to be sure). But it is not a tool that provides an obvious path to pushing through a piece of legislation of your own. The only way to do that is to win majorities in the House and Senate — and, whatever elections Democrats may have won last week, none of them brought the party any closer to 51 senators or 218 House seats.

Ultimately, if a policy is not supported by majority party leadership in the House and Senate, it is very difficult to get it passed. Extending the heightened Obamacare subsidies lacked such support, and therefore it was always going to be an uphill climb to get them re-upped. (Note that a bill to extend the subsidies by one year has only 14 Republican cosponsors in the House, which is not nothing, but far from the “majority of the majority” that Johnson would have been looking for before scheduling a vote — at least without the go-ahead from Trump, which, as we’ve discussed, never arrived.)1 There is little evidence that shutting the government down helped Democrats achieve this goal, if for no other reason than Republicans were resistant (as Democrats have been in the past) to setting the precedent that shutting the government down can lead to a policy victory, which would effectively ensure that the government would always shut down, since every minority party in the future would demand the same treatment.

(That said, even if the shutdown was a (predictable) policy failure, Democrats still appear to have achieved some of their political goals, in that the Obamacare subsidies have now been made a more salient issue ahead of the 2026 midterms. After all, from a political angle, it was always going to be more advantageous for Democrats for the subsidies not to be extended.)

Once the above realizations set in — namely, that Trump would sooner bully Republicans into ending the filibuster than agree to a deal on health care (but that, in reality, neither outcome was particularly likely) — a group of Senate Democrats clearly came to the decision that they would rather end the shutdown than continue threatening food stamps or Thanksgiving travel.

“Weeks of negotiations with Republicans have made clear that they will not address health care as part of shutdown talks — and that waiting longer will only prolong the pain Americans are feeling because of the shutdown,” Shaheen said Sunday.

Of course, just because it was clear from historical experience that Democrats would win little more than peanuts from a shutdown, that doesn’t mean it was made clear to the Democratic base, who are now expected to revolt against their party’s leadership.

This was always the biggest issue facing Chuck Schumer here. After rank-and-file Democrats responded with fury to his March decision to keep the government open, it was clear that Schumer was going to have to agree to a shutdown in October to please the base.

But, barring some unprecedented shutdown victory, Schumer was going to have to disappoint his base eventually — whether on October 1, November 1, now, or a month from now — by pulling the plug on a standoff that was never going to yield much success. Schumer never really tried to manage expectations otherwise, and now he’s trying to have it both ways by reportedly blessing the deal negotiated by his moderate flank in private while trashing it in public.

The base doesn’t seem to be buying it. It is becoming increasingly clear that opposition to Schumer and the Democratic Party’s current leadership will be a major litmus test in 2026 and 2028 primaries: Democratic Senate candidates across the country bashed the deal last night, with some of them pledging to oppose Schumer as leader in 2027.

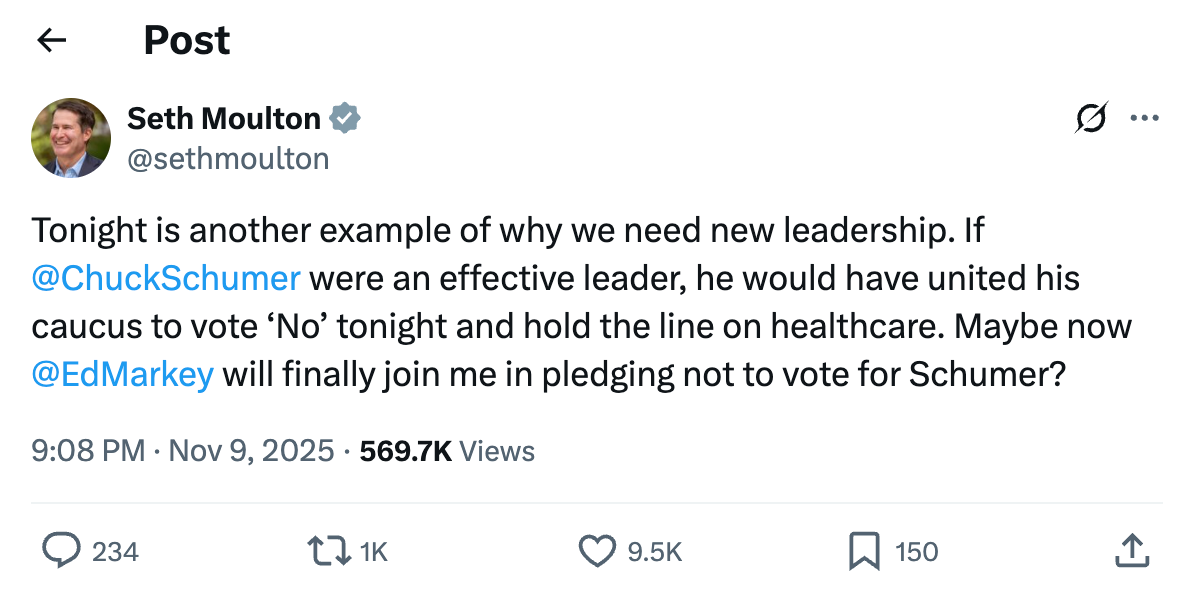

See, for example, Rep. Seth Moulton (D-MA), who is challenging Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) in a primary next year:

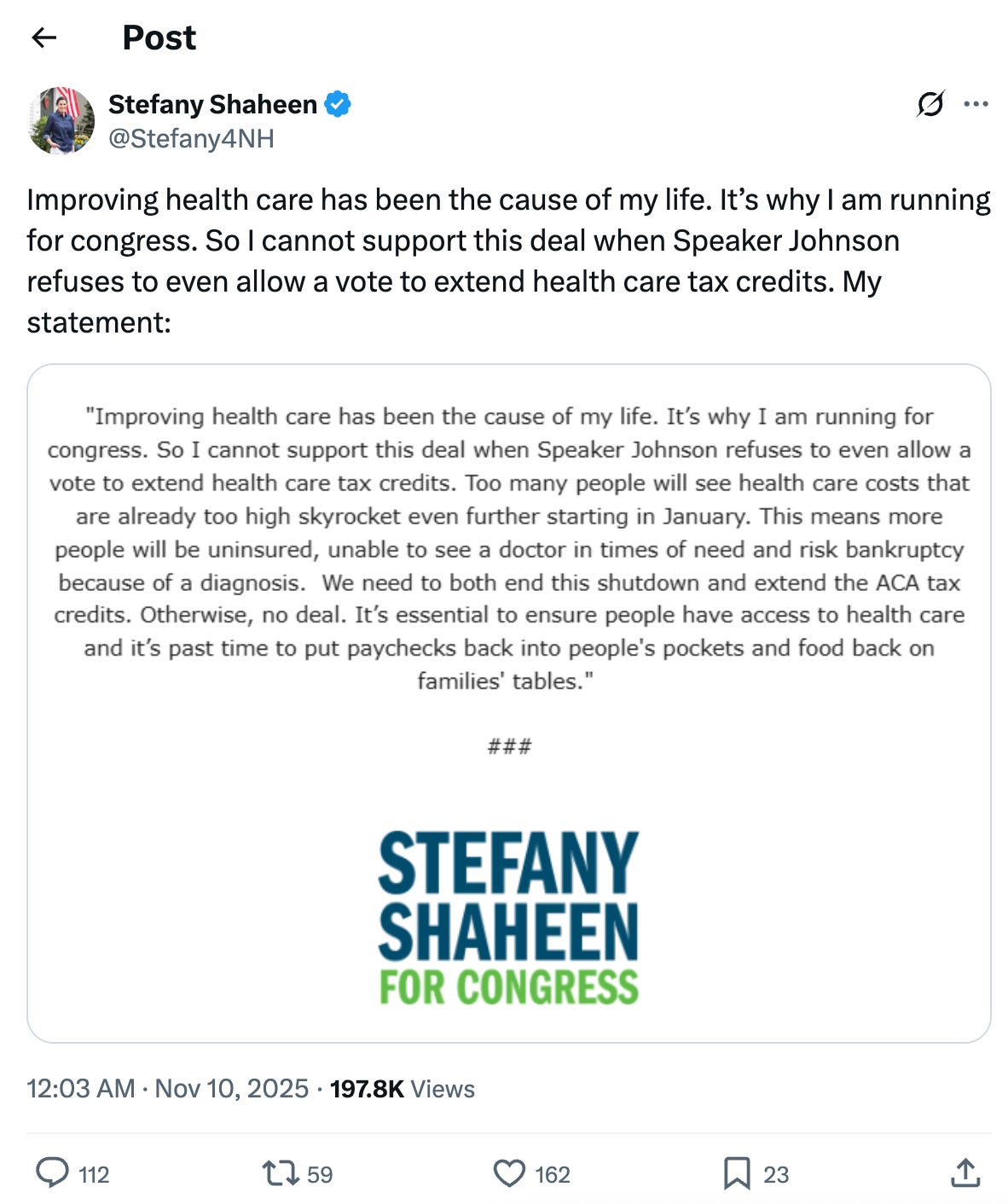

Distancing oneself from this agreement is such a requirement in Democratic primaries nowadays that even New Hampshire congressional candidate Stefany Shaheen — whose own mother crafted the deal! — released a statement condemning it:

That’s going to be one awkward Thanksgiving dinner.

Although this current shutdown will likely be forgotten by then, the broader idea that Schumer and other Democratic leaders aren’t up to the task of taking on Trump will likely also become fodder for the 2028 Democratic presidential primary. See Govs. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) and JB Pritzker (D-IL) lambasting the deal, and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) calling for Schumer’s ouster. All three are likely 2028 candidates.

There’s one more question to consider before we go: will we be right back here on January 30, when the new government funding bill is set to expire?

It’s very possible. Things will be slightly different by then. We’ll see how the slated December vote on Obamacare subsidies go, and whether bipartisan negotiations get anywhere by then. Notably, because three appropriations bills are poised to be approved as part of this week’s deal, a January shutdown would be only a partial shutdown, affecting only programs under the nine other appropriations bill that remain unpassed.

Since the Agriculture appropriations bill is part of the “minibus” receiving approval, SNAP would be funded during a January shutdown — removing one pain point that could make it easier for Democrats to opt for a second go-around. The Legislative Branch bill is also part of the package, which means congressional staffers would continue being paid next shutdown.

Of course, none of that means Democrats would have a very strong chance of achieving their policy priorities with a second shutdown — but, then again, there wasn’t a very strong chance they’d achieve anything with this one, and that didn’t stop Schumer from pulling the trigger out of fear of losing his leadership suite.

All that said, there is a way to force a vote in the House even if the House speaker doesn’t want to schedule a vote on something that isn’t supported by a majority of the majority. That route is a discharge petition, which requires 218 members to sign on.

There are 218 House members on record in support of extending Obamacare subsidies, although it is unknown if the Republicans in that number would be willing to buck Speaker Johnson and sign a discharge petition.

I wonder if one route out of this (that would have led to a win for Democrats) would have been to persuade the pro-Obamacare-subsidy House Republicans to sign a discharge petition, and then convince Thune to agree to a Senate vote on the House-passed bill. But there are all sorts of obstacles to discharge petitions Johnson could have thrown up, and Thune might not have agreed to a deal that would have actually led to a subsidy extension becoming law — which only goes to show that the Democrats’ policy ask seems to have lacked sufficient support in either the House or Senate, which means it was never going to be achieved without extended bipartisan negotiations (which themselves were never going to take place without the shutdown over).

Good piece. I greatly appreciate the relatively balanced, very well-informed, and refreshingly facts-based info that Gabe provides. His views do not always align with mine, but there is so much good info in his reporting that I don't see elsewhere that I'm very willing to skip over the occasional embedded opinion I don't share. I don't read just to hear myself anyway. Thanks, Gabe.

Good analysis, thanks for the historical context.