How close was the 2024 election?

And other mailbag questions.

Good morning! It’s Tuesday, November 12, 2024. Inauguration Day is 69 days away.

We are in the thick of the presidential transition — and I have all the latest for you below on President-elect Donald Trump’s appointments. But, first, I want to tackle a few mailbag questions I’ve received from readers since the election.

You all sent in a lot of questions, and I was only able to fit in a few this morning, but I’ll plan to do another mailbag column soon to tackle more questions that came in. Let’s dive in!

Were the polls wrong?

Brent B. asks: “Once again all the major polls seemed to have it all wrong, at least based on results to now. The race was nowhere as close as they indicated either nationally or in the swing states. The normally reliable Iowa poll even had it wrong. Would appreciate your analysis of this phenomenon. Or do you think the polls still have anything to say?”

Leslie G. asks: “I’d be curious to see your thoughts on why you and almost everyone else I read kept saying that the election was a 50-50 split when it turned out to be far from that.”

Ken P. asks: “Many highly-respected polls were seriously wrong during the campaign. To what extent do polls affect the vote? Also, please elaborate on the Bradley/Wilder Effect: That respondents intentionally lie to pollsters. Does the margin for error take the effect into consideration? Does the margin for error actually invalidate the poll?”

With all due respect, I’m going to have to disagree with the premise of these questions. There is no doubt that Donald Trump scored an impressive victory last week: he won all seven closely contested states. He was the first Republican since 2004 to win the popular vote. The margins in nearly every county in the U.S. shifted in his direction.

But two things can be true at once. Trump’s victory was impressive and also this was still a close election. Nate Silver estimates that the popular vote will land at Trump 49.9%/Harris 48.5%; all but one of the swing states are on track to be decided by 3.5 percentage points or less. I really don’t see any way to read those results other than an affirmation of the polls and analysts who said the race would approximate a 50/50 split.

To look more closely at how the polls performed in this election, here’s a chart that takes the last three elections and compares the final FiveThirtyEight polling averages and the election results in this cycle’s seven key battlegrounds. (Note that the 2024 results aren’t final, and I’ve used Silver’s estimate for the national result this year. Also note that this year’s seven battlegrounds weren’t necessarily the same states that were most closely contested in 2016 and 2020, but most of them were, so I’ve stuck to these seven for ease of comparison.)

The first thing that jumps out here is that the polls uniformly underestimated Trump for a third cycle in a row. In the three elections Trump has run in, polls have underestimated the Democrat in any of these states exactly once: Hillary Clinton in Nevada, 2016. Other than that, Trump has consistently ran ahead of his polls in all seven states.

That’s obviously a problem for the polling industry, and suggests there’s more work to be done capturing Trump’s support in surveys.1 But it’s also clear from looking at this chart that the polls have gotten better at doing so: not only is the average polling error down from the previous two cycles, but there wasn’t any major polling misses like there were in 2016 and 2020. In all seven states, the polls got within ~3 points of nailing the final margin; there were no misses of five points or more, like we saw in Wisconsin and North Carolina in 2016 or Wisconsin and Michigan in 2020. (Hats off to Wisconsin pollsters, who went from being the least accurate in 2016 and 2020 to being the second-most accurate in 2024.)

Nailing the results within 3 points is about as spot-on as we can reasonably expect the polls to be; anyone asking for more than that is asking for too much. If you see, say, a Harris +1.2 polling average, a Trump +1.4 win should absolutely be in your mental range of potential outcomes. And, as I warned you on Election Day, because polling error often moves in the same direction in a certain cycle, if polls in all the swing states are razor-thin, you should absolutely expect for most (or all!) of them to swing to the same candidate (as six of these seven did in 2016 and 2020, and all seven did this time).

To put the closeness of this election in historical perspective, if you were to take all 59 presidential elections and order them by percent of Electoral College votes received by the winner (most to least), Trump’s 2024 victory would rank as #39 — perfectly respectable, but still firmly in the bottom half. His 312-electoral-vote victory ranks slightly ahead of the 306 that he won in 2016 and that Biden won in 2020, but falls behind both of Obama’s elections (365 in 2008 and 332 in 2012) and certainly behind historical landslides like Reagan (525 in 1984) and LBJ (486 in 1964).

By popular vote (again using Silver’s estimate, where Trump is on track to win a plurality but fall just short of a majority), this was also a historically close election — continuing our modern trend of historically close elections.

And if you take the margins in each state, as Marquette’s Charles Franklin does here, it’s also pretty clear that the seven states we thought would end up around the 50-yard line… all did.

None of this takes away from Trump’s win, which included impressive swings in his direction across the country and is poised to come with majorities in the House and Senate as well. But the polls said this would be a close election, and it was one.

How should the Democrats respond?

Kyle N. asks: “Strategically and politically speaking, what do you think the Democratic Party’s main goal should be going forward? What do you think they SHOULD do, and what do you think they WILL do?”

Let’s separate the short and long term here. In the short term, if history is any guide, all the Democrats need to do is sit back and reap the same advantages of non-incumbency that arrayed in Republicans’ favor this cycle.

A dirty little secret is that Americans don’t like dramatic policy changes and, despite the fact that they often send politicians to Washington demanding such change, voters usually get frustrated with them pretty quickly when they try to deliver it. In short: voters hate the status quo — until someone tries to change it, and suddenly they hate the new status quo even more.

In political science, this is known as the thermostatic theory of public opinion, and it’s the reason why presidents’ parties almost always perform poorly in their first midterms. Presidents run against incumbent parties promising big new policies, then they become the incumbents themselves and try to enact new policies (Obama and Obamacare, Trump and Obamacare repeal), and voters punish them for it.

In all likelihood, this same pattern will repeat itself with Trump. Most experts agree that both mass deportations and universal tariffs would have adverse economic consequences, including exacerbating inflation (which, as we learned anew this cycle, voters are particularly sensitive to). If the president-elect succeeds in carrying out these and other proposals, it will likely spark voter backlash and allow Democrats to win a House majority in 2026.2 Suddenly, a party now in the wilderness will have its foot in the door; the fluke circumstances that helped contribute to their losses (Biden’s age and unpopularity; global frustrations about Covid-era inflation; a rushed nomination process) will melt away and be replaced by new fluke circumstances that will likely hurt Republicans.

But that’s only the short-term. In addition to the fluke circumstances, there were, of course, also more existential factors that hurt Democrats. The country remains close enough to 50/50 (see above) that the party’s current coalition could certainly return it to the White House with the right conditions (and, crowded as it is with high-propensity voters, could definitely lead the party to victory in the 2026 midterms). But, in the long term, the party would be wise to look for ways to broaden its coalition, so that its victories aren’t contingent on the right alignment of fluke circumstances leaning their way. (This is true of both parties, by the way, but as per the question, I’ll focus on the Democrats for now.)

At the highest level, Democrats have clearly lost their ancestral branding as the party of the working class, and unless they win it back, they will continue to lose support from low-income voters of all racial backgrounds and be reliant on a coalition of highly educated professionals who are enough to win midterms elections but not enough to win higher-turnout presidentials.

There isn’t a specific set of policy prescriptions that will automatically revive that branding, and you should be skeptical of anyone who says there is. But, at least attitudinally, Democrats would probably be wise to embrace a more economically populist image, channeling voter distrust of institutions rather than dismissing it. That will likely require elevating leaders who come outside of politics and law — whether it’s former bartender AOC to the left or former mechanic Marie Gluesenkamp Perez to the center — and who can authentically speak to voters’ struggles and frustrations with Big Business, Big Academia, Big Everything.

It will also likely require facing the fact that the party is out of step with many non-college-educated voters (of all races) on social issues. 69% of Americans say transgender athletes should play on teams that align with their birth gender. 68% agreed with the Supreme Court’s decision to end affirmative action for college admissions. 55% say U.S. immigration levels should be decreased. 53% support a border wall.

These all represent issues Democrats are on the losing side of. Does that mean they have to change their positions on all these issues? Not necessarily. It’s possible to win an election holding minority positions. But it’s a lot harder to win an election, as a party holding minority positions, if you look down on and judge (or even brand as hateful) the people in the majority. That’s a surefire recipe for failure.

To take one example, after the election, Rep. Seth Moulton (D-MA) told the New York Times: “I have two little girls, I don’t want them getting run over on a playing field by a male or formerly male athlete, but as a Democrat I’m supposed to be afraid to say that.”

Moulton is now facing progressive backlash and staff resignations — and, of course, those activists and aides have every right to protest. But, according to Gallup, only 34% of the country agrees with them. That doesn’t mean every Democrat has to adopt the 69% side of the issue; but, at the very least, the 34% side can’t expect political success if they shame the ones who do.3 34% does not add up to a winning coalition.

CNN reported on a focus group with a woman in Pennsylvania who called the Republicans “crazy” and the Democrats “preachy,” and said she was leaning towards the Republicans. Why? “Because ‘crazy’ doesn’t look down on me,” she said. “‘Preachy’ does.” That’s the type of perception the party has to reverse.

A lot of Democrats are not fans of the Senate filibuster — but it’s worth remembering that the most recent party to build a filibuster-proof Senate majority was the Democrats, in 2009. Democrats would be wise to dwell on what it required to build that type of broad-based, 60-seat coalition, rather than a coalition that hovers around the 50%-mark — maybe just ahead, maybe just below, but never very far from it.

It required Democratic senators in California, and Vermont, and Massachusetts, sure — but also two Democratic senators in Arkansas, Montana, North Dakota, and West Virginia, and one each in Alaska, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, and South Dakota.

And that required a high degree of comfort with ideological heterogeneity. Democrats who were pro-life. Pro-gun. Anti-gay marriage. Broadening their tent, not shrinking it. In the short-term, Democrats can probably get away with the coalition they have, considering the thermostatic nature of our politics and their support from high-propensity voters. But if they want a more durable, longer-term coalition — one that doesn’t keep draining support from multi-racial, working-class, culturally conservative voters, then they need to understand how those voters think on economic and social issues — and start becoming comfortable with elevating at least some voices who think in the same ways.

Can Trump talk to foreign leaders?

Nancy M. asks: “How can Trump be making deals with Putin and involving Musk in conversations with Zelensky? He is not president but he is conducting foreign policy?”

Presidential transitions are weird. In fact, former White House official Joshua Zoffer wrote a paper in 2021 arguing that they are “lawless” — stuck in a legal gray period where a president-elect drafts executive orders, nominates appointees (who often receive confirmation hearings even before Inauguration Day), and does other president-like things without actually being the president.

Talking to foreign leaders is another one of those things. Technically, the Logan Act of 1799 prohibits U.S. citizens from “directly or indirectly” carrying on negotiations with a foreign government if they don’t have authority from the U.S. government. But no one has ever been convicted of violating the Logan Act (and only two people in history have even been charged with it, both in the 1800s). As Zoffer writes:

Despite the Logan Act’s statutory prohibition on foreign policy-making without “the authority of the United States,” Presidents-elect have a long history of bucking the Constitution and doing just that. Within five hours of his election, then-President-elect Eisenhower transmitted a “message of friendship” to France. Eisenhower also took a trip to Korea during his transition period, during which he met with South Korean President Syngman Rhee, who insisted on offering his views on American military strategy in the Korean War. After all, from President Rhee’s perspective, Eisenhower had far more sway over the war than Truman from that point on.

The Eisenhower example is especially relevant here because — like Trump — Eisenhower campaigned on a promise to end a foreign war without specifying how he would do so. “I shall go to Korea,” Eisenhower famously said as a candidate; as president-elect, he did. (The war indeed ended six months into his presidency.)

Although foreign travel is less typical, presidents-elect generally speak to a range of world leaders during the transition. Among others, Trump has spoken to the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, China, Canada, France, the UK, India, South Korea, Israel — the list goes on. It’s a weird legal gray area, but it is not at all uncommon.

The Trump transition, so far.

A complete list of the Trump administration picks we know so far:

White House chief of staff: Trump campaign manager Susie Wiles

Deputy White House chief of staff: Longtime Trump adviser Stephen Miller

Secretary of State: Florida Sen. Marco Rubio

Secretary of Homeland Security: South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem

UN Ambassador: New York Rep. Elise Stefanik

National security adviser: Florida Rep. Michael Waltz

Immigration czar: Former acting ICE Director Thomas Homan

EPA Administrator: Former New York Rep. Lee Zeldin

Some early takeaways:

Heavy representation from Florida and New York, Trump’s two home states.

A clear emphasis on rewarding politicians who have been loyal to him, even in case like Noem where they have little experience in the relevant field.

Miller and Homan signal an intent to carry out a heavily restrictionist immigration agenda.

Rubio, Stefanik, and Waltz signal a hawkish foreign policy, much closer to previous iterations of Republican neoconservatism than “America First” isolationism.

Picking Stefanik and Waltz will eat into what will likely be a slim House GOP majority — potentially leaving Republicans with a one- or two-seat edge. These seats will eventually filled by special elections (in which Republicans will be favored), but while they remain vacant, it will require House Republicans to remain highly united on any party-line votes… something House Republicans have not had a great track record of doing in recent years.

The day ahead

President Joe Biden will meet with Israeli President Isaac Herzog, have lunch with Vice President Kamala Harris, and meet with Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto.

The Senate will vote to confirm April Perry as a U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Illinois.

The House is expected to vote on a bipartisan bill to repeal the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) and Government Pension Offset (GPO). Read more here

The Supreme Court will hold oral arguments in Velazquez v. Garland and Delligatti v. United States.

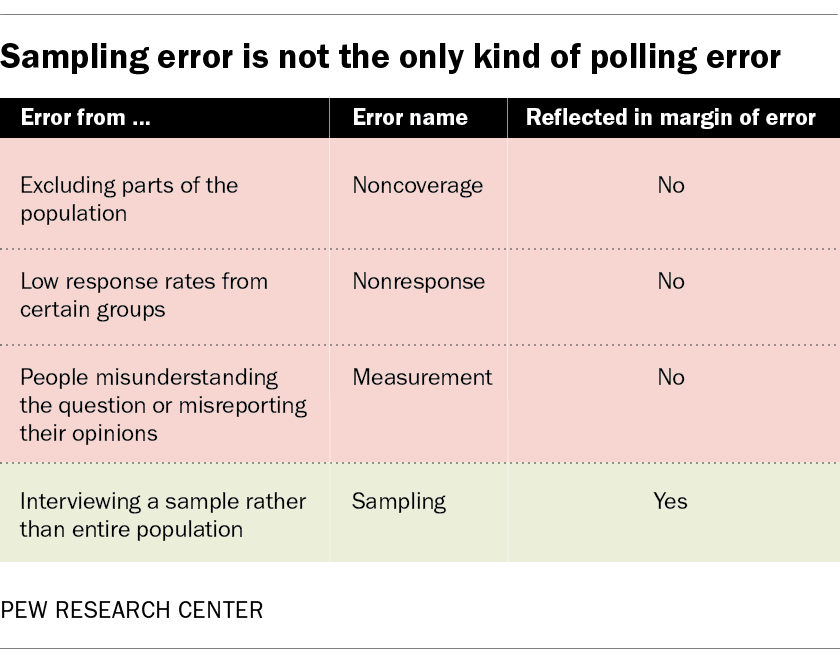

The questioner asked about respondents lying to pollsters, so I wanted to address that here. First off, no, that possibility isn’t included in a poll’s margin of error. It’s important to keep in mind that sampling error (accounting for the possibility that a poll’s random sample will deviate from the actual population in unpredictable ways) is the only type of polling error reflected in margin of error. Measurement bias, where voters misreport their answers, is among the types of error not reflected.

Another error not reflected is nonresponse bias (low response rates from certain groups). Personally, I found this thread from a pollster to be a compelling argument that nonresponse bias, not measurement bias, has more to do with pollsters’ struggles capturing Trump’s support — but, obviously, there’s more investigation on the matter yet to be done.

Winning the Senate majority in 2026 will be a very heavy lift for Democrats, requiring them to flip Maine (doable without Susan Collins), North Carolina (maybe doable in an off-year), and two additional seats from a list of possibilities that includes Alaska, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Nebraska, and Texas (all much harder). At the same time, they’ll have to defend seats in Georgia and Michigan.

After this newsletter was published, CNN reported that Tufts University, which is located near Moulton’s district, was “breaking ties” with Moulton over his comments, telling his office “not to contact Tufts about future internships.” It now appears that Tufts has reversed the ban, which was reportedly put in place by the chair of its political science department, but the fact that a highly-placed academic even tried to isolate Moulton is a great example of coalition-shrinking and those with minority positions trying to shame the majority.

Wow great read today, Gabe! Thanks again! Good and thorough answers to some of the questions; and that was a great educational session about polls. I will try not to ignore them as much, they seem to be more accurate than I realized.

First time commenter here!

I appreciate your analysis, but I am getting very frustrated with so many post-mortem takes blaming support for Trans Rights as what has hurt the dems. It was a very low portion of the campaign's messaging, and--if anything--so much of the discussion about Trans Rights was because Republicans made it an issue over the past few years-passing awful laws at the state level that caused a panic about participation in sports, threatened families of trans kids, and caused panic about drag story hour. It was the republican's party's lies and disinformation that caused this rift, and hurt countless children and families in the process.

I strongly urge readers to read Parker Molloy's substack about this discourse:

https://www.readtpa.com/p/fine-lets-talk-about-trans-athletes

https://www.readtpa.com/p/the-anti-trans-blame-game-predictable

If we are not careful, there will only be more harm for Trans individuals across the country.