DOGE’s Final Failure

Is it easier to destroy than to build?

Happy Thursday morning! My apologies: this newsletter should have come out yesterday. It ended up needing some extra research time; I hope you find it worth it. I’ll still be back in your inbox tomorrow.

This newsletter partially came from questions sent by readers; as always, you can send questions to Wake Up To Politics here.

I. Out of options

If at first you don’t succeed: try, try again.

Around a year ago, officials working at Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (better known as DOGE) fanned out across the U.S. government and tried to effectively eliminate a series of small agencies.

DOGE placed almost all the staffers of AmeriCorps, which oversees a network of community service programs, on administrative leave and ordered the termination of almost half of the agency’s grants. Musk’s team called for the staff of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provides research and education grants, to be slashed by as much as 80% and for all Biden-era grants to be cancelled. The entire staff of the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which gives funding to museums and libraries, was put on leave. Musk derided Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, the government-funded international broadcasters, and moved to have them shuttered.

These efforts generated a blitz of news coverage, but all ran into legal obstacles. In September, the Trump administration confirmed that all AmeriCorps funds for the fiscal year were being spent, after a judge ordered the agency’s staff and grants to be restored. The humanities and library grants were also restored by judges. Voice of America’s footprint has reduced significantly, but hundreds of employees have been reinstated by a judge; broadcasts have been scaled back, but not stopped as Musk has hoped.

Foiled in its attempt to unilaterally dismantle arms of the government, the Trump administration then tried another tack: it went to Congress. (What a concept!) Per PBS News, in his budget request for Fiscal Year 2026, Trump asked lawmakers to eliminate 46 different federal programs, including the four mentioned above.

Also: the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, a $4 billion program that helps low-income Americans pay to heat their homes. The Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, which investigates industrial chemical accidents. The Administration for Community Living, which assists older and disabled Americans hoping to live independently. An interagency council on homelessness. An office at NASA that promotes STEM education. And more.

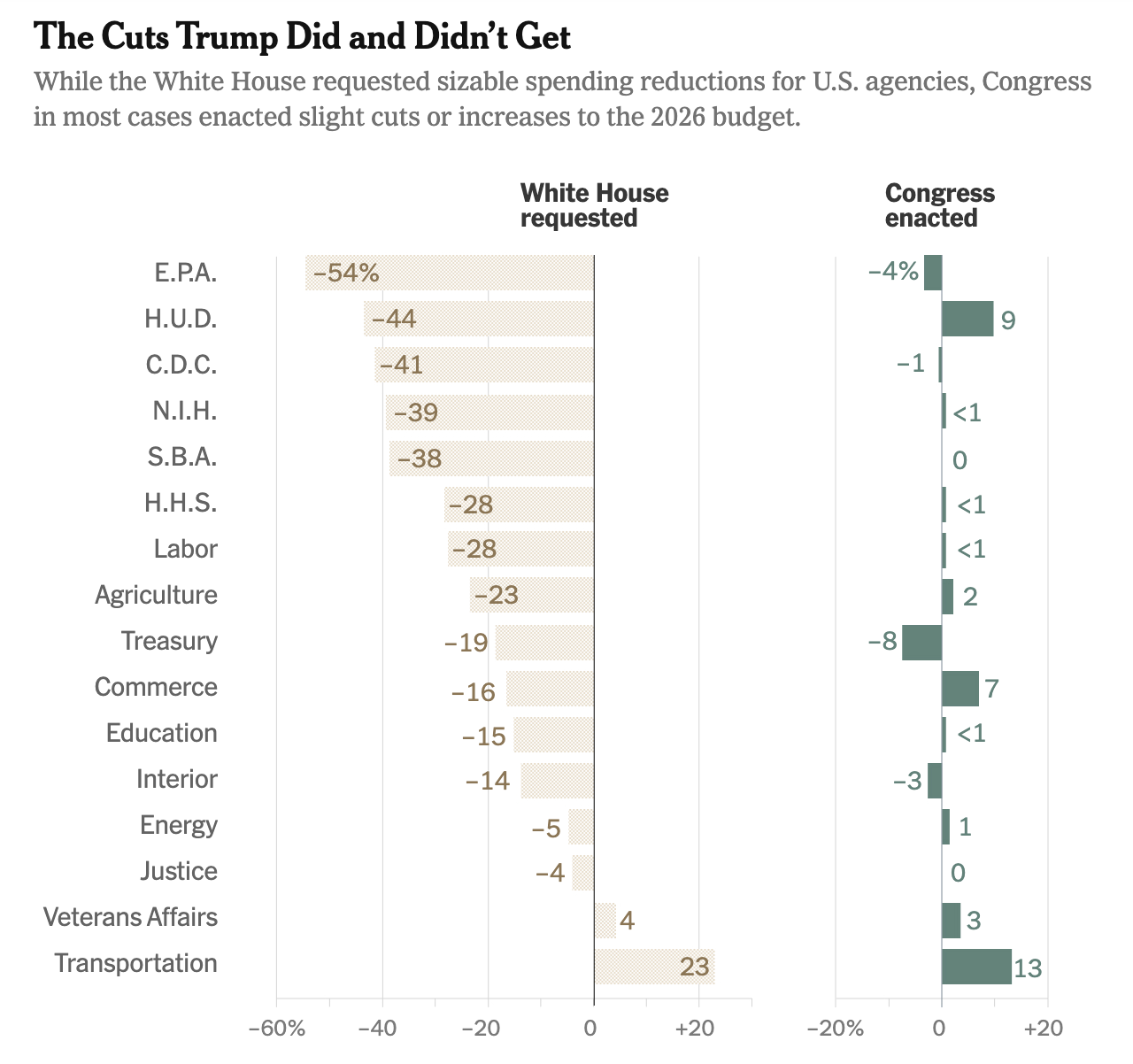

As of this month, President Trump has signed nearly all Fiscal Year 2026 spending into law, across three legislative packages (see here, here, and here). According to a Wake Up To Politics analysis of these laws, Congress rejected 44 out of Trump’s proposed 46 eliminations. In most cases where Trump sought to zero out an agency’s funding, the agencies were instead given around the same level of funding as in previous years; in some cases, the targeted programs even saw funding boosts.

Only two of Trump’s elimination requests were met. No funding was awarded to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which helps fund PBS and NPR, after the organization closed its doors in response to a law passed by Congress in July stripping away its funding. And Congress agreed to close the Office of Navajo and Hopi Indian Relocation, which had already been winding down after largely completing its mission.

Beyond those two exceptions, lawmakers ignored the president’s attempt to close an array of agencies. For instance, hoping to finish what DOGE started, Trump requested $0 for AmeriCorps and the U.S. Agency for Global Media (Voice of America’s parent agency); they were awarded $1.25 billion and $653 million, respectively. Other examples abound.

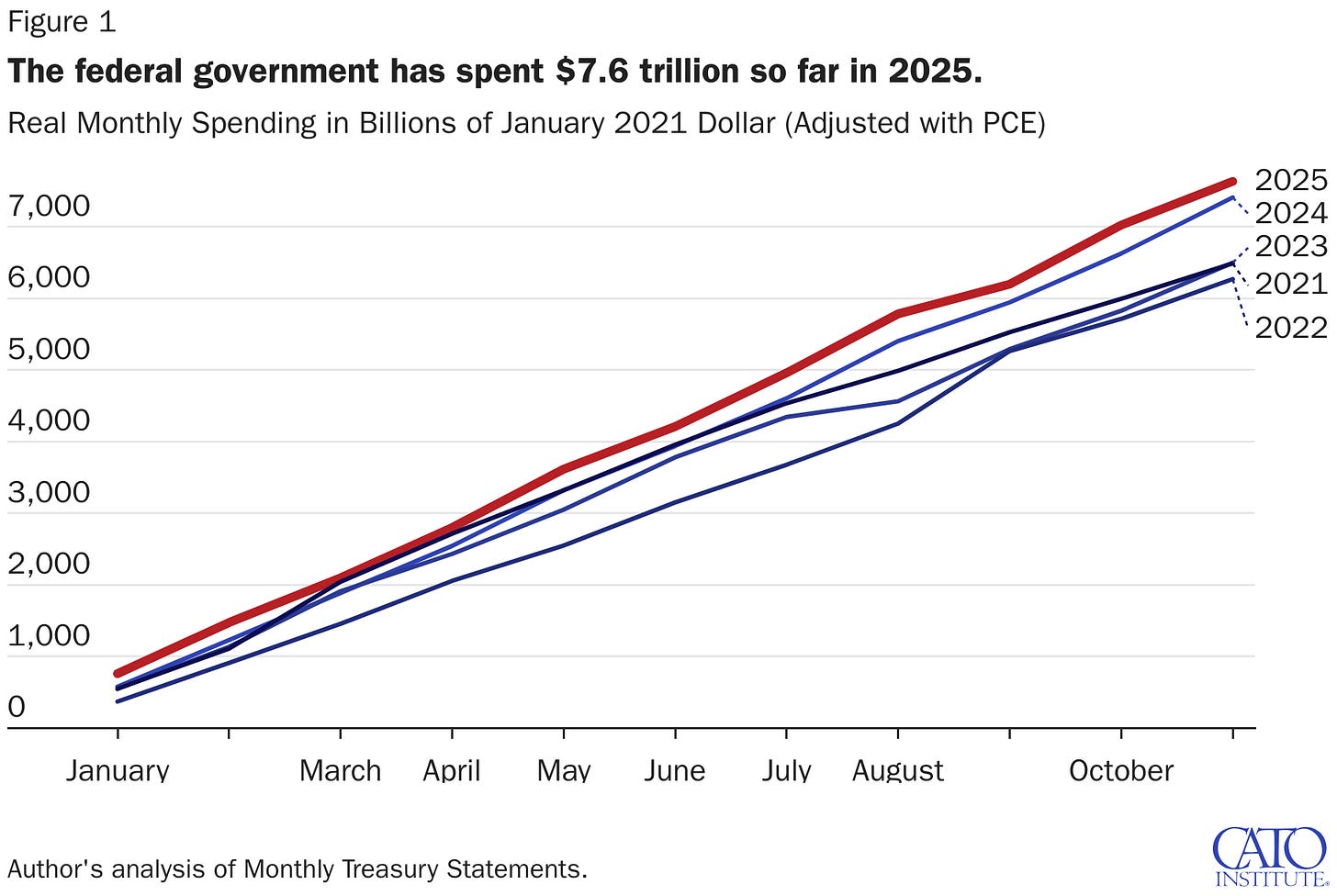

It is already known that DOGE came nowhere close to its goal of slashing $2 trillion in government spending by executive action: government spending actually increased in 2025, partially because social safety net programs continued to balloon. As Alex Nowrasteh, the Cato Institute’s senior vice president for policy, has noted, “an observer who did not know when DOGE started could not identify it” from the below chart.

Elon Musk has long since fled Washington, but the new bipartisan appropriations laws should be considered the final nail in DOGE’s coffin, and for Trump’s broader promise to slash the federal budget. With their enactment, not only has Trump failed to cut spending by executive action; Congress has declined to let him do it by statute as well.

These laws are “entirely a rejection” of Trump and Musk’s efforts, Nowrasteh told me in an interview.

II. Checkmate?

Last week, I argued that Donald Trump has built little of substance in his second term; by staking his presidency on executive actions, I wrote, he had ensured that his accomplishments will quickly collapse like sandcastles, rather than lasting as sturdy structures.

I received thoughtful responses from several readers, who noted that this analysis focused on what Trump has tried to build, but neglected what he has tried to knock down. Here’s one:

Though while Trump isn’t *building* much that will last, he’s also *tearing down* a lot, which will have more lasting impact. The East Wing of the White House may not have been destroyed by legislative action, and thus the next president can un-do, re-do, or do whatever they want with it. But they can’t magically bring it back to what it was with the stroke of a reverse executive order. And that feels like a metaphor for a lot of other things he’s done too (shutting down various agencies, etc)

There is certainly truth to this. To take this reader’s example, the East Wing has indeed been knocked down, and no president can change the fact that that part of the White House, at least in its previous form, has been reduced to rubble. That’s a change that will stick. (The ballroom that Trump wants to put in its place, however, may be blocked by a judge this month.)

Has Trump managed to implement similarly lasting changes at federal agencies?

The most obvious example that comes to mind is the U.S. Agency for International Development, better known as USAID.

22 U.S. Code § 6563 tells us that “unless abolished pursuant to the reorganization plan submitted under section 6601 of this title [which said that such a plan could only be submitted before 1999] and except as provided in section 6562 of this title [which concerns certain functions of USAID’s predecessor agency] there is within the Executive branch of Government the United States Agency for International Development.”

That remains on the books as U.S. law. But the Trump administration says that no such agency is functioning. “As of July 1st, USAID will officially cease to implement foreign assistance,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio wrote last year. “Foreign assistance programs that align with administration policies—and which advance American interests—will be administered by the State Department, where they will be delivered with more accountability, strategy, and efficiency.”

Here, Trump has largely gotten his wish. 83% of USAID contracts were scrapped and nearly all of the agency’s 4,700 employees were put on leave or terminated.

This is not to say that no foreign aid has been disbursed in Trump’s second term (billions of dollars have been, administered by State directly, instead of USAID). But there has been a sharp reduction, which has had an enormous impact. Modeling by Boston University epidemiologist Brooke Nichols estimates that more than 800,000 lives have been lost as a result of U.S. aid cuts. Even if you’re skeptical of those sorts of projections, there have been numerous observable consequences. Consider the following, from the Center for Global Development:

Extensive award cancellations and payment delays have led to widespread and numerous cases of stock-outs of lifesaving medicines and widespread service suspension. US cuts to the World Food Programme’s operations in Yemen alone ended lifesaving food assistance to 2.4 million people and stopped nutritional care for 100,000 children.

There is on-the-ground evidence of resulting impacts: Rising malnutrition mortality in northern Nigeria, Somalia, and in the Rohingya refugee camps on the Myanmar border and rising food insecurity in northeast Kenya, in part linked to the global collapse of therapeutic food supply chains. Spiking malaria deaths in northern Cameroon, again linked to breakdown in the global supply of antimalarials, and a risk of reversal in Lesotho’s fight against HIV, part of a broader health crisis across Africa.

This is absolutely relevant to any consideration of the Trump administration’s long-term impact.

Has he successfully shuttered other agencies?

We know the answer is “yes” in the case of the Corporation of Public Broadcasting — and that this has led to layoffs at some public media stations that relied on its funding — but “no” for the other agencies Trump tried to eliminate in his FY 2026 budget (except for the Office of Navajo and Hopi Indian Relocation, of course).

Most other targeted agencies are in some degree of limbo.

For example, Trump has signed an executive order saying that “the Secretary of Education shall, to the maximum extent appropriate and permitted by law, take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Department of Education.”

What extent is “permitted by law”? We’re still finding out. The agency tried to lay off about 40% of its workforce in March; a district judge and appeals court panel blocked the move, but the Supreme Court allowed it, without giving any explanation of the justices’ reasoning.

That litigation decided the temporary posture of the case. Now, the case continues to work its way through the courts, in order to determine the final outcome. Just last week, Judge Myong Joun ordered the Trump administration to produce certain documents to build an evidentiary record as he decides whether the firings should be seen as typical layoffs (which are within the executive branch’s authority to carry out) or as a backdoor attempt to eliminate the agency (which is not within the executive branch’s power).

In the meantime, the states that brought the original case filed an amended lawsuit last month alleging that the layoffs are preventing the agency from carrying out its statutory obligations.1

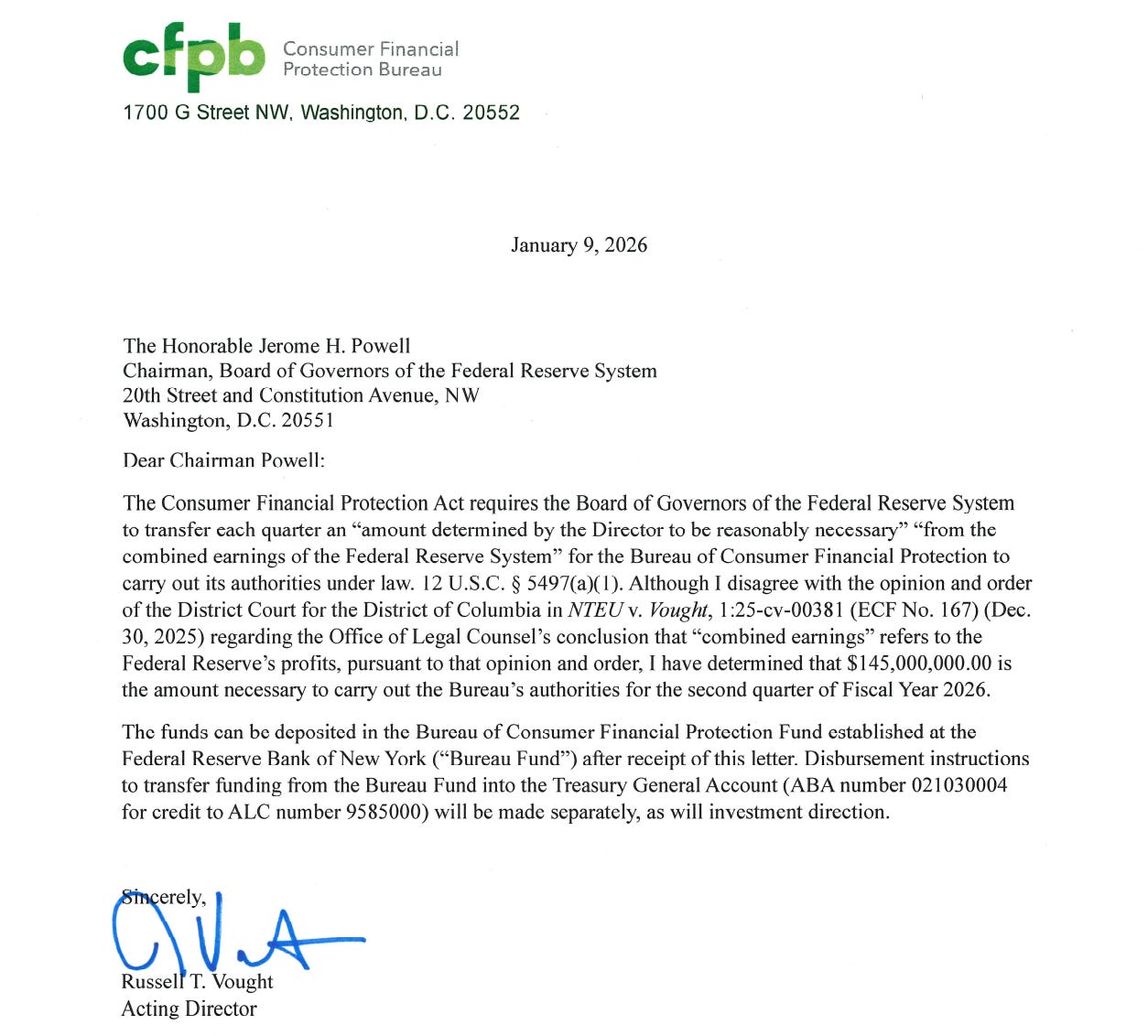

A similar story can be told about the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), another early DOGE target. An attempt to lay off nearly the agency’s entire staff was blocked by a court, then allowed, then blocked again in December. The CFPB gets its funding from the Federal Reserve, not Congress, and amid all this, there was a side-dispute when the White House didn’t ask the Fed for any CFPB funding, trying to get around unfavorable court rulings by effectively saying, “OK, maybe we can’t shut down this agency, but the agency can’t function unless the Fed gives it money, which it won’t do unless we ask for some. So we’ll just not ask for anything, and then the CFPB can’t do anything. Checkmate!”

Reader, it was not checkmate. Judge Amy Berman Jackson ruled that this was an attempt to subvert court rulings and illegally shut down the CFPB by other means; she ordered CFPB director Russell Vought (who is also the White House budget director) to ask the Fed for money. In January, Vought did so, sending a letter to Jay Powell saying “I disagree with the opinion” of the court but complying anyway. He asked for $145 million, which was probably around the maximum he could have requested after the One Big Beautiful Bill lowered the agency’s funding cap.

All of this chaos and back-and-forth means these agencies have significantly scaled back their activities — but for our purposes of assessing long-term impacts, it is far from clear that these have been achieved as permanent closures. These court cases are still ongoing2, and in the CFPB example, it remains to be seen what will happen now that the agency has requested a budget and has been blocked from moving forward with layoffs relatively recently.

These are all situations very much in flux, with new and forthcoming developments to watch, from Judge Joun’s recent order for documents on the Education Department firings to hear oral arguments scheduled to be head next week in an appeals court on whether the CFPB layoffs should stay blocked.

III. Puzzle pieces

There’s a bit of a puzzle here.

Why have the USAID and CPB shutdowns been successful, while Trump’s attempts to throttle other agencies have run into legal trouble?

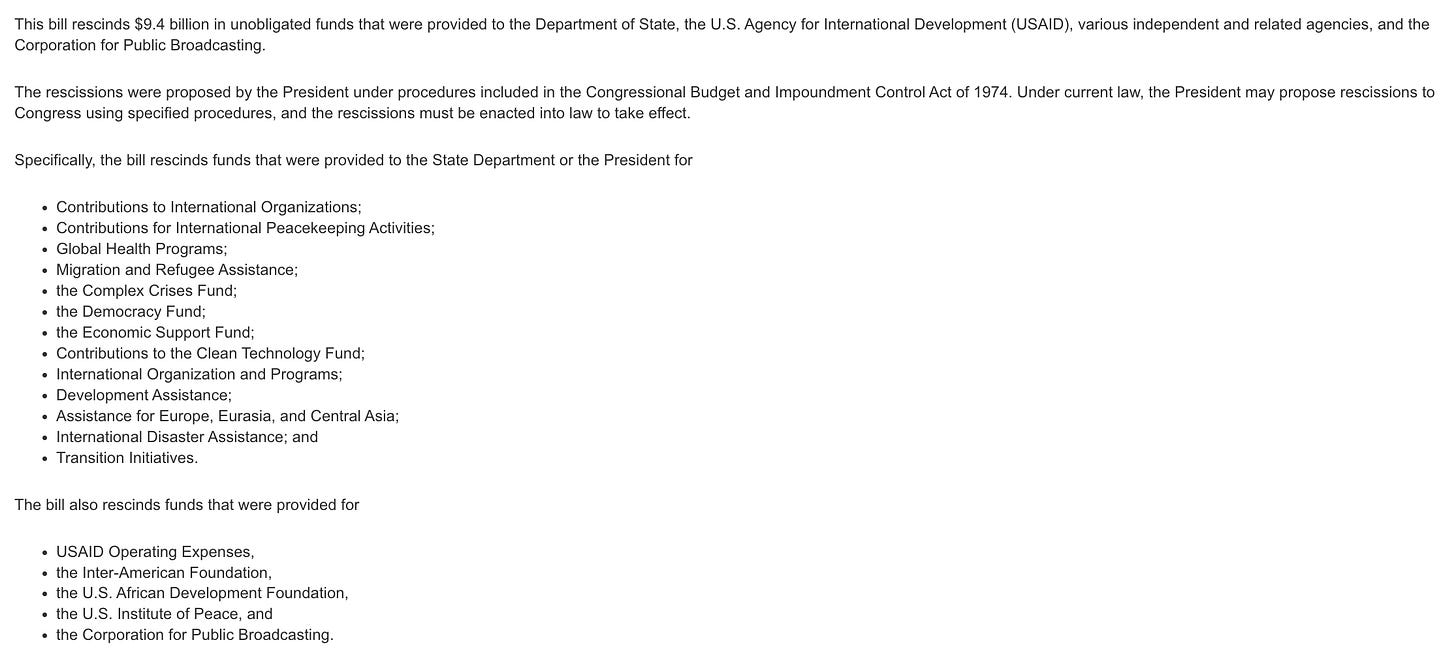

The answer lies in Public Law 119-28, the Rescissions Act of 2025, summarized below:

The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 provides exactly one way for the president to cut spending outside of the normal appropriations process: by sending something called a “rescissions package” to Congress, proposing certain spending cuts, which they can then either approve or reject.3

Trump asked to rescind $8.3 billion in funding for USAID (and other foreign aid programs) and $1.1 billion in funding for the the CPB, all of which Congress approved, and then rescinded $5 billion more from USAID through a backdoor tool called a “pocket rescission,” which I covered here.

This helps explain why government spending barely budged as a result of DOGE, but spending on foreign aid fell by $12 billion last year, according to the Brookings Institution’s Jessica Riedl. This decline basically overlaps with the two rescissions packages, Riedl noted.

Of course, defunding USAID is different than being able to formally shut it down as an agency (which would be harder to reverse than merely re-funding it). Apart from the cases on foreign aid funding, there is also a pending court case on that question, and there are new developments here, too: Judge Theodore Chuang ruled this month that Elon Musk could be deposed as part of a case on the constitutionality of DOGE’s actions to dismantle USAID.

The question of whether Trump has succeeded here is still being answered, even if it has mostly receded from the headlines. But as with Trump’s attempts to construct policy, it is clear that his attempts to tear things down are at their most vulnerable when not blessed by Congress, as seen in the divergent fates of USAID and the CPB versus, say, the CFPB or the Education Department.

The new appropriations laws — which were negotiated in a strikingly bipartisan process — were like adding another anti-blessing from Congress towards Trump’s attempts to destroy various agencies, which will only give more grist to his opponents in the courts. Plaintiffs in the Voice of America case have already pointed to the appropriations in new legal filings, citing Congress’ continued funding of the agency as further proof that trying to close it is contrary to legislative intent. (Congress also declined to cut funding for the Education Department, and continued to fund $50 billion in foreign aid, well above Trump’s request. In addition, the appropriations laws added various guardrails to block Trump from unilaterally meddling with federal spending.)

Executive actions should primarily be seen as time-bound because they are vulnerable to being overturned by the courts or by a future president, but in some cases, it hasn’t even taken that long: sometimes, Trump’s attempts to cut various programs haven’t even survived his own administration.

Hundreds of workers fired by DOGE were later re-hired after the administration realized they were needed. The administration has also brought back nuclear staff, FDA scientists, and officials at the Justice Department “peacemaker” unit. Last month, the Department of Health and Human Services reinstated mental health grants 24 hours after cutting them. The National Institutes of Health ended up spending its full budget last fiscal year, after a “frenzy of grantmaking” right at the end meant that the agency caught up from significant delays earlier in the year.

That said, Trump has clearly succeeded in shrinking federal employment, leading to the largest peacetime cut to the government workforce on record, according to the Cato Institute’s Nowrasteh. Again, there is no question that this will have a real impact on government operations and on the lives of these employees. But there is also little guarantee that the cuts will stand as long-term accomplishments. If workers have been fired, but Trump has not gained legislative approval for slashing an agency or its budget, then statutory authority and funding will exist for a future administration to easily grow the workforce back.4 Live by executive action, die by executive action.

IV. Amateur hour

On a podcast last week, former President Barack Obama noted that “for all the hoopla, [Republicans] haven’t actually codified and institutionalized much of anything,” having only “passed one significant piece of legislation,” the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

Obama then went on to make a similar point as some WUTP readers, arguing that Trump is mainly “trying to unravel a bunch of rules and norms and laws that are already in place,” which he said was an “easier” task because it doesn’t require putting together “working majorities to actually pass laws” like building things does. “Tearing stuff down doesn’t require all that,” Obama said.

He said this after his interviewer, the progressive commentator Brian Tyler Cohen, decried the “massive asymmetry” of Democrats focusing on “protecting norms, institutions, processes,” while “you’ve got a Republican Party that sees what it wants and will find a way to get it, laws be damned, Constitution be damned, rules be damned.”

“It often leaves us feeling like it’s a ‘Lucy pulling the football away from Charlie Brown over and over and over again’ situation,” Cohen said, indicating that he believed it was time for Democratic officials to change that mindset and asking Obama whether they had.

This is why it’s important to take a step back and analyze how Trump’s agency-slashing efforts are going: if officials in both parties believe the efforts under Trump have worked, then President Gavin Newsom (or whoever else) will try the same thing with ICE or President JD Vance (or whoever else) will try to finish the job with the Education Department … only to both run into disappointment, because they learned the wrong lesson from the Trump era.

The lesson is not that tearing things down requires any less of a legislative majority than building things up does, as shown by the fact that Trump’s only truly successful tear-downs — the ones not still snarled in court battles — are the ones he was able to get a congressional majority to support. Tearing things down unilaterally can generate a lot of chaos, and a lot of headlines, and even a period where things grind to a halt or are consumed by confusion, giving the appearance of victory. But it is much too early to say that tearing things down unilaterally works.

Strangely, one lesson from the Trump era (for those willing to learn it), may end up being the importance of respecting process. Accomplishments are only secure when codified by legislation, and even more secure when codified by bipartisan legislation, which means they have garnered the support of a broad-based majority and are unlikely to soon be overturned. This is something our most successful presidents have understood, and it’s something that has become clear once again in the Trump era, even as the president has tried to promote the appearance of success via unilateral action. Cutting corners (mostly) hasn’t worked; Trump’s most successful efforts to tear down agencies have still happened through a congressional process.5

Another lesson, for presidents of either party, will be the importance of surrounding yourself with people who understand that process.

This may seem like an obvious point, but clearly it bears repeating. With some key exceptions — Vought is one, White House policy chief Stephen Miller is another — President Trump has largely surrounded himself with officials lacking experience in the agencies they’ve been tapped to run. This has backfired for Trump repeatedly.

One example can be seen in a recent Wall Street Journal piece on Kristi Noem’s leadership of the Department of Homeland Security (here is a gift link). One year ago, immigration was Trump’s strongest issue; you can easily imagine, had he put the right person in charge of the agency with jurisdiction over the issue, that support for his handling of immigration — and, thus, his overall popularity — might be much higher today.

Instead, he picked Noem, who has “fired or demoted roughly 80% of the career ICE field leadership” and ignored the advice of other experienced hands who recommended that the administration focus its efforts on deporting illegal immigrants who have committed crimes since entering the U.S. In addition, according to the Journal, Noem’s top aide Corey Lewandowksi has reportedly punished multiple officials for not being “willing to issue him and several other political officials badges and guns.” That is, well, one way to make personnel decisions. The result has been a slapdash immigration policy, which has, incredibly, made one of Trump’s greatest political strengths become one of his greatest vulnerabilities in just a year.

Or consider the Atlantic’s reporting that Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick bungled trade negotiations with Japan by misunderstanding the terms they had agreed to … or Reuters’ reporting that Trump’s ubiquitous (and inexperienced) diplomat Steve Witkoff had made a similar mistake with Russia. (By the way: whatever happened to the promised peace deal in Ukraine?)

To take another recent example, a grand jury last week unanimously rejected the Justice Department bid to criminally charge six Democratic lawmakers — which truly never happens. (The grand-jury-unanimously-rejecting-charges part. OK, well, also the charging-members-of-Congress-for-a-video part.)

That’s a really embarrassing failure. Maybe it had something to do with the fact that, per Bloomberg, one of the prosecutors who tried to bring the charges was a dance photographer whose only prosecutorial experience was on the local level, decades ago, and the other had only served a brief stint as a federal prosecutor?

It turns out that if you want to successfully run a government — whether “success,” to you, means expanding bureaucracy or slashing it — it helps to have people who know about the government.

And the same is true of Trump’s attempts to slash the government, which were similarly foiled by a lack of expertise.

“DOGE tried to get rid of the experts,” Jessica Riedl, the Brookings Institution economist, told me in an interview. “DOGE fired the inspectors general. They tried to defang [auditing agency] GAO, and they shut out all of the economists and budget experts who have been identifying waste because they determined that everybody who understands the federal budget is part of the swamp and part of the problem.”

“Government waste is very easy to identify and very difficult to eliminate,” Riedl said. “If you want to eliminate program overpayments, you have to overhaul the computer systems in thousands of different agencies and programs. You have to change the payment processes, you have to build new auditing systems, and you have to do all of this in a way that doesn’t paralyze the provision of benefits for those who are eligible. It is a very lengthy, tedious, even expensive process to do that for thousands of agencies and programs, and it requires a lot of time, expertise and congressional oversight.”

“There are no shortcuts,” Riedl added, “and a competent war on waste would have built that sort of infrastructure with Congress, with experts, and with some appropriations to overhaul the computer systems. And had they done that over a span of perhaps four to six years, they could have made significant savings in the federal budget.”

A more experienced team of budget-cutters might have focused more on areas where the executive branch has obvious power, like curbing regulations or investigating entitlement fraud, rather than taking legally vulnerable steps into Congress’ domain, the Cato Institute’s Alex Nowrasteh told me. (Reportedly, original DOGE co-chief Vivek Ramaswamy had been studying up to take exactly this path before Musk shoved him aside.)

“It was an Elon Musk project. He’s a populist from the outside. It was going to be his show, and it ended up being his show,” Nowrasteh said, adding that a more traditional approach “would have been more effective, but it would have been a little boring, a little less interesting, and Elon Musk would not have been in charge, and that ultimately is the reason why I think it didn’t happen. This really likes the big and dramatic. It likes a show. Empowering GAO to work with a panel to investigate Medicare and Medicaid fraud and overbilling. That’s not sexy.”

But might it have been more effective over the long-term?

“Oh, it would have saved a lot more money,” Nowrasteh said. “A lot more money.”

Many of the Education Department “cuts” have also taken the form of transferring its functions to other agencies, which is more temporarily moving stuff around than permanently tearing something down. “I mean, if you want to call that abolishing the Department of Education, fine,” Jessica Riedl of the Brookings Institution told me. “I call it changing the address on the stationery.”

Another interesting thing to note is that, time and again, Trump’s bluster about shutting down agencies has worked against him when he’s then tried to lay off workers or block grants. Repeatedly, judges have used his (or Musk’s) own words against them in their rulings, as they’ve blocked actions (like layoffs) that might otherwise be in the executive’s purview, but which start to smack of moving into the legislative domain of shutting down an agency once the president openly declares that to be his aim.

This is one way that tearing things down is easier than building them: It takes 60 votes to advance an appropriations bill approving spending, but only 51 votes to advance a rescissions bill clawing it back. It is, in fact, easier to cut spending than to raise it.

But that doesn’t mean it’s that easy! Trump had to pull a lot of teeth to pass the rescissions package (and ultimately accept changes to cut less than he had originally hoped). Notably, the Trump administration is reportedly not planning to send another rescissions package to Congress — which is revealing, considering that it has been their most successful way to cut spending, but likely an acknowledgment that tearing things down can be almost as difficult as building them, since it still requires a congressional majority (even if not a supermajority), which the administration apparently does not believe it could cobble together for another rescissions proposal.

It should also be noted that, per the administration, more than 90% of federal departures since Trump took office have been voluntary resignations (including many that took the DOGE buyout offer). This reinforces that employees leaving doesn’t inherently equal positions permanently cut, although their departures do represent a brain drain that will be impossible to immediately replace.

I say “mostly” because the use of pocket rescissions could clearly be defined as “cutting corners,” even if it nominally was a use of the formal rescissions process. The Supreme Court allowed the pocket rescissions to go forward at the end of the last fiscal year, in a decision the justices stressed was their “preliminary view,” not a “final determination on the merits.” However, that sidestepped the fact that the funds were poised to expire at end of the fiscal year, meaning their decision likely was a final decision for all intents and purposes. Indeed, just yesterday, an appeals court formally dismissed the case, effectively showing that the pocket rescissions gambit had succeeded.

Kudos on this this huge informative message. Let me add to the DOGE shitstorm:

In a whistleblower disclosure filed with Congress and corroborated by internal documents, NPR reports, Berulis said that the DOGE employees first set up a process to hide their activities on the servers, rather than allowing account activity to be tracked. This alone is a “red flag,” cybersecurity experts said, and a technique mimicking what a malicious hacker may use when trying to infiltrate government systems.

Berulis noticed soon after the raid began that a DOGE engineer was working on a “backdoor” to the NLRB’s case management system, which would allow the rogue group to extract information surreptitiously. Then, he saw within the system’s metrics that there was a massive spike in data being extracted from the network and sent to an unknown location that could contain a huge amount of case information.

Trump Is Trying to Axe Collective Bargaining for 1 Million Federal Employees

The IT worker first spoke out internally against the DOGE raid — but when he did, his attorney has said, someone taped a threatening note to his door that contained sensitive personal information about him, as well as pictures of him walking his dog that looked like they were taken by a drone. Whistleblowers have long faced threats to their personal safety, while recent high-profile cases of corporate whistleblowers have created a culture of fear around the practice.

Meanwhile, the information exfiltrated by DOGE includes a huge amount of sensitive information about American workers, including “ongoing contested labor cases, lists of union activists, internal case notes, personal information from Social Security numbers to home addresses, proprietary corporate data and more information that never gets published openly,” NPR wrote.

In other words, as labor experts said, DOGE may have gotten its hands on the names, addresses and Social Security numbers of labor organizers across the country — at a time when President Donald Trump and Republicans are preparing to majorly dismantle labor protections and attack workers’ rights, including unionization.

It also comes from rogue actors assembled by Musk — whose companies are involved in numerous labor disputes. This includes an alarming lawsuit, filed by SpaceX, challenging the constitutionality of the NLRB itself, which is the primary entity in the U.S. protecting workers from labor abuses.

Even if that data isn’t being actively used by Musk and his cronies, labor experts said that the fact that they can access it may have a chilling effect on the labor movement, just after it has seen a major resurgence in recent years.

“Just saying that they have access to the data is intimidating,” Kate Bronfenbrenner, the director of labor education research for Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations and co-director of the Worker Empowerment Research Network, told NPR. “People are going to go, ‘I’m not going to testify before the board because, you know, my employer might get access.’”

The extreme, malicious techniques used by DOGE to infiltrate the system, meanwhile, could also leave this data vulnerable to being seized by other bad faith actors. At one point just minutes after DOGE accessed the systems, for instance, employees noticed log-in attempts from an IP address located in Russia — attempts that used a newly-created DOGE account with the correct username and password.

One of the few lasting legacies of DOGE may be in the successful effort to reduce the federal workforce through intimidation and buyouts. Agencies experienced significant attrition and now have a massive reduction in expertise and administrative capacity that will be very difficult to repair. I fear people's collective short memories will forget what DOGE did to hollow agencies out, and they'll nod along when Elon's spiritual successors point to examples of agency dysfunction (caused by that lack of expertise and capacity) as reason why the federal government doesn't work and should be cur