An Alternative History of the Trump Era

The Hollywood fantasy that almost came true.

Because I hate myself, when I’m not busy covering politics, I often like to watch political TV shows in my spare time. (So much for escapism!)

I’ll watch anything, no matter how niche. A one-season rom-com about journalists covering a presidential campaign on the streaming platform go90, which I have never heard of before or since? Yes, please! A show on Epix (?) about a Reagan-like figure living life as a former president? I thought Nick Nolte gave a great performance!

One thing I’ve noticed in a lot of these shows is a recurring Hollywood fantasy about a candidate running for president as an Independent, who — without party labels to weigh them down — is able to unite the country and get things done, combining the best of the two party platforms.

It happens in CBS’ “Madam Secretary.” Ditto ABC’s “Designated Survivor,” another Trump-era show that tried to give viewers a break from overwhelming polarization by offering a dose of centrism. It never quite happens in NBC’s “The West Wing,” the ultimate political fantasy show (I don’t say this is an insult!), but it is kind of the dream behind moderate Republican Arnold Vinick’s run, before Vinick is tapped as the Democratic president’s secretary of state as a sort of bipartisan unity administration.

Fictional political consultant Bruno Gianelli, who switches parties to work for Vinick, says this to the California Republican at one point in the show:

[You are] exactly where 60% of the voters are: pro-choice, anti-partial birth, pro-death penalty, anti-tax, pro-environment, pro-business, and pro-balanced budget. You’re in a unique position to run a completely positive campaign because most of the country agrees with you on most of the issues… You can stop using politics to divide this country. You can show us how much we agree, instead of how much we disagree. You can put this country back together.

Movies like “Bulworth,” “The Candidate,” and even “Dave,” also have vaguely similar undertones: of common-sense leaders who bring people together by telling it like it is, even if it means offending party interests. (“Dave” also features a great scene with a mild-mannered accountant going through the federal budget line-by-line, doing basically what Elon Musk thinks he’s doing, minus the misinformation.)

The dewy-eyed idealist in me falls for this every time. But the hard-boiled realist in me knows better. Attachments to political parties (and their role in the ballot access process) are simply too strong, and whenever voters are offered these sort of third-party choices, they never go for them. Unity08 (2008), Americans Elect (2012), Evan McMullin’s campaign (2016), Howard Schultz’s near-campaign (2020), and No Labels (2024) are all in the centrist unity party graveyard. (Ross Perot in 1992 was the closest any Independent campaign came in memory, although — despite taking an impressive 19% of the popular vote — he failed to win a single electoral vote, proving the impossibility of this sort of task.)

This type of thing could simply never happen.

Except… it kind of almost did?

Reading news from early 2016 — not even a decade ago! — is like stepping into another dimension, one where no one really knew what to do with Donald Trump as a political figure, and certainly Republicans (now best known for their unwavering devotion to him) were not pleased about the idea of his hypothetical ascension.

One of the big Republican fears about Trump around the time was that he would betray the party and constantly be striking agreements with Democrats in Congress. We went through a whole news cycle (one that’s hard to remember now!) where Sen. Ted Cruz was constantly dropping the d-word — “dealmaker” — as his biggest attack against his then-rival, as a way to convince Republican primary voters that only he, not the mushy former Democrat Trump, would fight for conservative principles.

“Donald, just a couple of days ago, drew the difference between me and him, and he said, ‘Look, Ted won’t go along to get along, he won’t cut a deal,’” Cruz said in January 2016 while campaigning in New Hampshire. “So, if as a voter you think that what we need is more Republicans in Washington to cut a deal with Harry Reid and Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, then I guess Donald Trump is your guy. That’s what the Washington establishment is saying.”

Later that same day in Nevada, Trump scoffed at the allegation: “He’s trying to paint me as part of the establishment. And somebody said, ‘How come Sarah Palin just backed him? Establishment?’”

But then, in the same breath, Trump did something even more remarkable: he embraced the label. “There is total gridlock,” Trump said. “Guys like Ted Cruz will never make a deal, because he’s a strident guy. ‘No, you cannot have that!’ … You know what, there’s a point at which, let’s get to be a little establishment. We got to get things done, folks. We’re gonna make such great deals, but at a certain point, you can’t be so strident … We got to get along with people.”

“You know, in the old days,” he continued, “Ronald Reagan would get along with Tip O’Neill and they’d sit down and make great deals for everybody. That’s what the country’s about, really, isn’t it?”

That November, a critical swath of voters came around to this view of Trump as a common-sense centrist — perhaps because his GOP rivals had tilled the ground for him so nicely, or perhaps because of his genuine shifts away from Republican Party orthodoxy, on issues like trade, entitlements, foreign interventions, and even several social issues. (It’s always interesting to remind people that Donald Trump was the first president to enter office having supported same-sex marriage. He also, in his first campaign, said transgender people should use whatever bathroom “they feel is appropriate.” I told you 2016 was like a different world!)

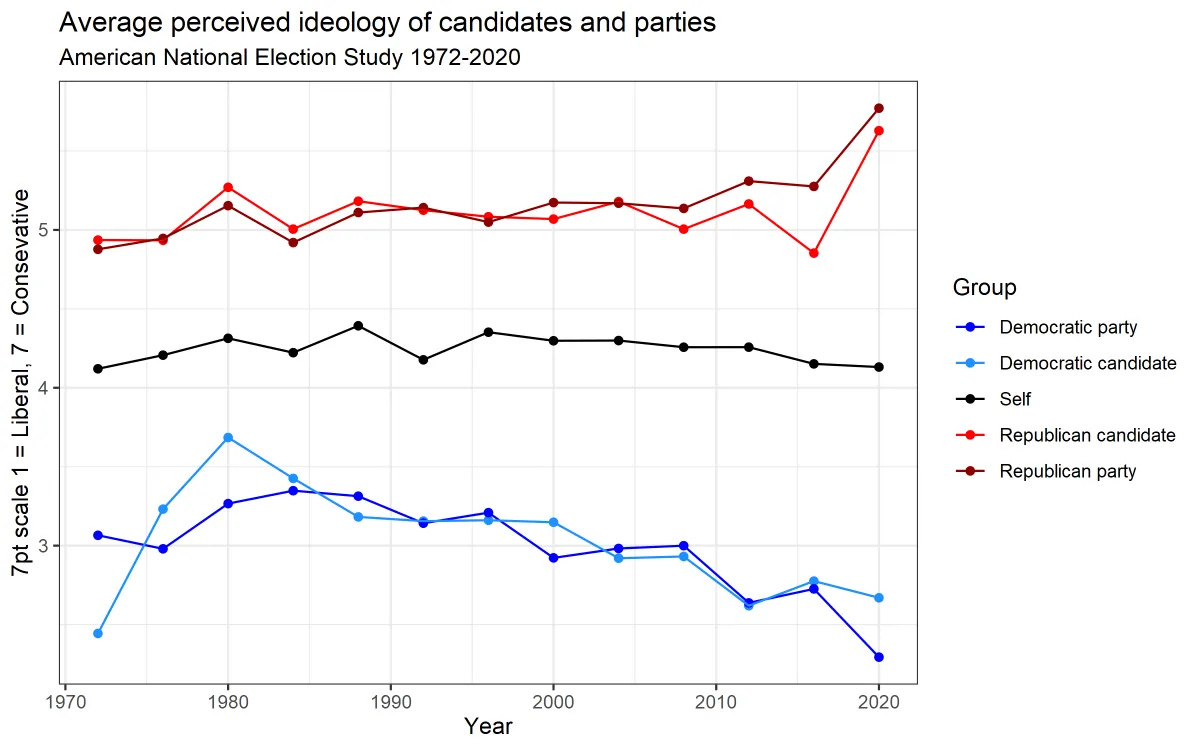

I’ve used this graph in the newsletter before, but I just find it so fascinating: in 2016, voters viewed Trump as the most moderate Republican presidential candidate since the 1970s (and sharply more moderate than the GOP as a whole). By 2020, he was viewed as the most conservative Republican candidate on record. I think that explains a lot about why he won one of those elections and lost the other.

But let’s stay in 2016 for a second, because after Trump was elected, there were genuine questions about what it would look like for such an outsider to sit in the Oval Office. “Could bipartisanship rise with Trump government?” The Hill newspaper asked. In The Washington Post, the wise Dan Balz called Trump “America’s first independent president” and noted that “no one has a clue” if Trump would govern as a “disrupter” or a “dealmaker” (or perhaps even a combination of the two).

For a moment there, it seemed possible that Trump might really scramble the partisan lines that had dictated American politics, realigning the two parties and governing without allegiance to either one. With the benefit of hindsight, we now know Trump chose the “disrupter” option — but even for stretches of his presidency, it was clear that he was drawn to his self-image as a dealmaker, inspired by the Reagan/O’Neill example he mentioned on the campaign trail.

He started his administration bashing Democratic congressional leaders Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi — but, after his partisan Obamacare repeal push floundered, he began wondering if working with the other party might bear more fruit. In September 2017, Trump shocked Republicans by striking a deal with Schumer and Pelosi (or “Chuck and Nancy,” as he called them at the time) to raise the debt ceiling, extend government funding, and offer disaster aid.

It was like Ted Cruz’s worst nightmare came to life. “Republicans, sorry, but I've been hearing about Repeal & Replace for 7 years, didn’t happen!” Trump wrote on Twitter two days later. “Even worse, the Senate Filibuster Rule will never allow the Republicans to pass even great legislation. 8 Dems control - will rarely get 60 (vs. 51) votes.” Trump had pivoted to bipartisanship. “Bound to No Party, Trump Upends 150 Years of Two-Party Rule,” The New York Times declared.

The very next week, another shock arrived, when Schumer and Pelosi exited a Chinese-food dinner at the White House and declared that they had inked an immigration deal with Trump, agreeing to enhanced border security in exchange for codifying protections for “Dreamers” into law. Trump pushed back, saying an agreement hadn’t been struck, but basically confirmed the broad contours of the pact.

“He likes us. He likes me anyway,” Schumer, his fellow New Yorker, was heard saying on a hot mic around this time. “Here’s what I told him. I said, ‘Mr. President, you’re much better off if you can sometimes step right and sometimes left. If you have to step just in one direction you’re boxed.’ It’s going to work out and it’ll make us more productive too.”

But congressional Republicans exploded in anger, and Trump eventually backed away from the negotiating table. This same thing would then play out in 2018, when Trump appeared to embrace a gun control deal before being talked out it by the NRA, and in 2019, when Trump, Schumer, and Pelosi agreed to pursue a bipartisan $2 trillion infrastructure package before the talks blew up amid the intensifying congressional investigations into his presidency. Democrats could have impeachment or infrastructure, Trump essentially told them, but not both.

They chose impeachment, and he never forgave them. As 2019 turned to 2020, a darker chapter of Trump’s presidency emerged. It’s not as though there were no bipartisan deals in this period — the Covid stimulus packages come to mind — but Trump wasn’t very personally involved in them, leaving figures like Steve Mnuchin to do the negotiating.

To me, this is the great “what-if” of the Trump era. What if Trump had entered office, and actually tried to strike popular deals with Democrats: building infrastructure, lowering drug prices, enhancing border security while protecting certain immigrant groups? Might he have cobbled together the sort of durable political majority that has eluded both parties for decades, while also achieving major policy objectives across party lines?

Trump arrived better positioned to do this than any president in recent memory: it may be practically impossible for an Independent to be elected president — but Trump figured out a work-around. He was simply an Independent who took over an existing party machine (and ballot line). His support in the party was so strong that it’s possible he could have forced Republicans to accept deals that no other president could have gotten them to vote for.

Instead, the reverse happened. It’s popular to say Trump brought the GOP to heel — that he is “bound to no party,” as the Times put it — and in some important ways, that’s true. But in other respects, Republicans have subjugated him, forcing him to the right on several key policy areas relative to where he was in 2016. Almost every time he came close to achieving bipartisan policy change in his first administration, instead of pressuring Republican leaders to accept it, they pressured him to abandon the agreement, convincing him that his base would desert him if he struck a deal, even though he campaigned on exactly that premise.

And on top of that, of course, it quickly became clear that — despite having authored a book called “The Art of the Deal” — political dealmaking was never in Trump’s personality. Unlike Reagan and O’Neill, who bickered all day but were able to be friends after six o’clock, Trump simply took every slight too personally.

For those reasons, there were never really questions about how Trump would govern when he took office for the second time last month.

A Pew poll in December 2016 found that 51% of Americans thought it was “somewhat” or “very” likely that Trump would work with Democrats on “important issues facing the country” once he became president.

The same poll, ahead of his 2024 election, found that number had dropped to 36%. Ahead of his first term, even 31% of Democrats thought it was at least somewhat likely that Trump would work with their party’s leaders; by his second, only 7% of Democrats said the same.

And yet, he was gifted with the same opportunity again — maybe even a bigger one.

Republicans are now even more willing to accept anything Trump hands them: Ted Cruz may have warned about Trump working with Democrats in 2016, but he’ll surely vote for former Democrats Tulsi Gabbard and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (despite the HHS pick’s longtime stance on abortion being wildly different than Cruz’s own) when they come up for Senate confirmation votes.

And Democrats — much more in 2016 — were sufficiently demoralized by their 2024 defeat that they appeared much more willing to move in Trump’s direction on key issues and ink bipartisan deals as well. “The fact that we work across the aisle really matters to people,” Sen. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ) said in December. “If we’re always just raising the alarms and fighting, we’re going to be seen as not being even-handed players.”

“It can’t simply be ‘Oh, it’s a Trump idea, we oppose it,’” Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) echoed.

Trump seemed to notice: “In the first term, everyone was fighting me,” he said during the transition. “This time, everyone wants to be my friend.”

Needless to say — and to no one’s surprise — Trump has so far opted against adopting the model of bipartisan governance that he at least flirted with the first time around. With Elon Musk’s help, he has run roughshod through the government, dismantling entire agencies and refusing to spend money in violation of congressional statute.

Those moves have lost him whatever bipartisan goodwill he might have had on Inauguration Day. Last month, a group of Senate Democrats wrote a letter to GOP leaders offering to work on a border security compromise; this week, several of the signatories now said a deal was off the table after Trump’s impoundment efforts.

If you think 2016 is hard to remember, try turning your mind back just two months ago. As recently as December 2024, a chorus of House Democrats — again, this is how cowed the party was by Trump’s victory — expressed willingness to work with Elon Musk on his “Department of Government Efficiency,” or DOGE. So much for that. Now, Democrats who joined the DOGE Caucus are already leaving in protest of Musk’s tactics.

At this point in the piece, you might be saying, “Well, of course.” What’s in it for Trump to work with Democrats on legislation if he can just govern by executive action?

This represents a flawed theory of the presidency, as Yuval Levin — a scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute — reminded Ezra Klein in a recent podcast interview:

I think our modern presidents in particular have so internalized this kind of deformed sense of their role that they don’t see that, ultimately, their success depends on legislative action. They think they can be remembered for being great presidents for their administrative actions.

And it’s just not true. Who are the modern presidents we think highly of? It’s Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. What was the New Deal? The New Deal was legislation. What was [Lyndon Johnson’s’] Great Society? The Great Society was not a set of administrative actions. It was big bills that the president shepherded through. He certainly gave them a lot of direction, but there was a lot of negotiation that was not about him in that process.

Ronald Reagan’s tax bill was not just Ronald Reagan’s tax bill. A lot of Democrats voted for that bill because they were involved in negotiating it, and they got some things they wanted in it. And at the end of the day, we call it Ronald Reagan’s tax bill anyway, because we remember our presidents for the legislative achievements that their leadership makes possible.

Lasting legislation, not easily overturned executive actions, represent a president’s best ticket to the history books. And the best — often only — way to achieve legislation is through bipartisanship.

At one point, Trump himself recognized this: “We don’t want to sign executive orders,” he said, incredibly, at that same 2016 rally in Las Vegas. “We want to make good deals.”

Oftentimes, it is not in a president’s interest to attempt bipartisanship, out of fear that the resulting legislation won’t have political benefits for their party, since the opposition will be able to share credit. An alternative version of Donald Trump might see that he — more than any recent president — has little reason to care about such things: he never has to run for political office again, and it’s not like he cares too much about the future of his party. Anything he does now is only for his legacy.

Except that is quite obviously not how Trump is approaching his second administration, seemingly motivated more by vengeance than by legacy — despite the fact that his acts of revenge are his least popular policy ideas.

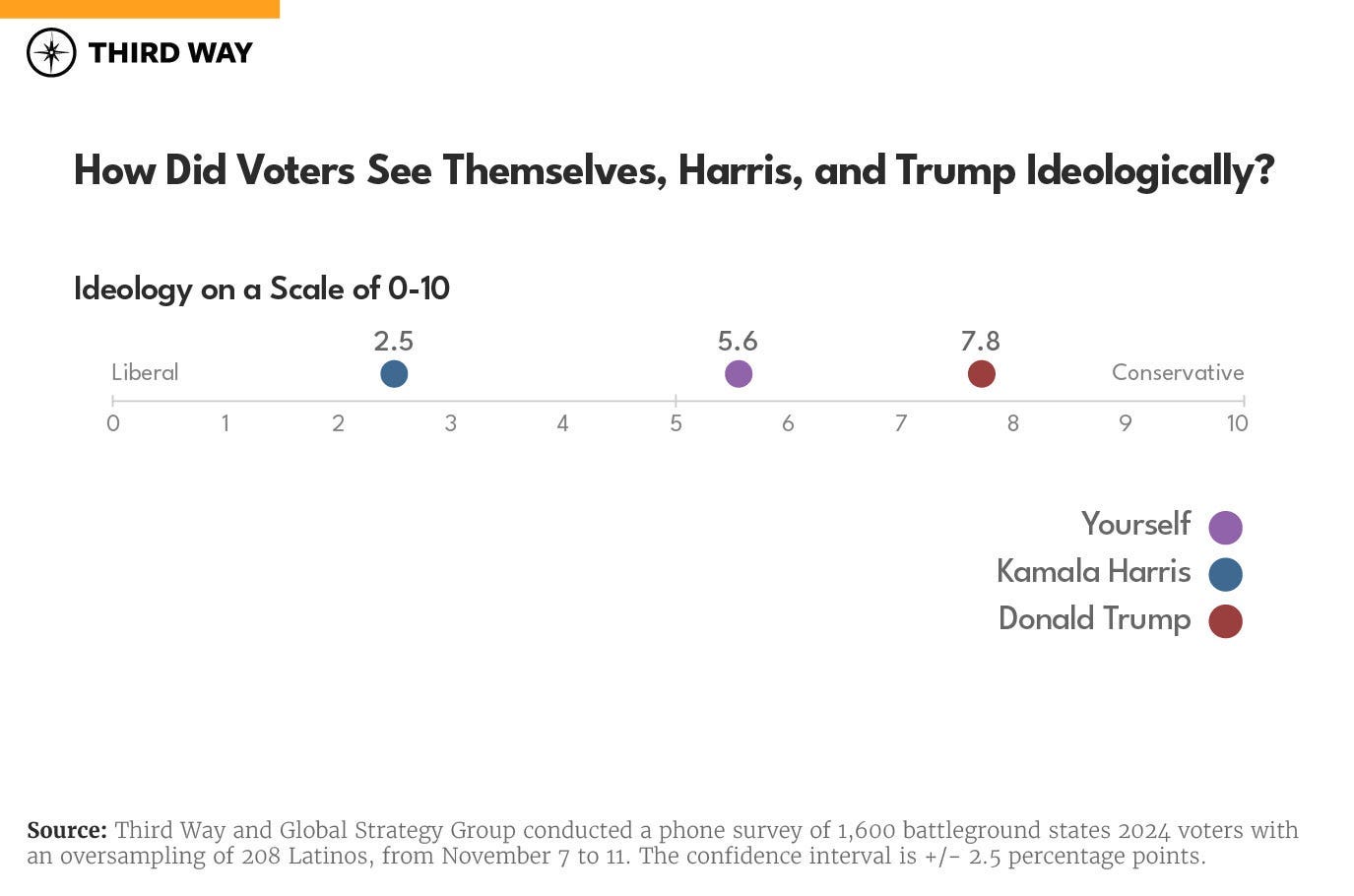

In the 2024 election, after sanding down his rhetoric on issues like abortion, Trump was able to recapture his reputation as a relative moderate. If he wanted to secure that image in the public’s eyes, and ink a lasting legacy for history, he would have a menu of transformative policy choices before him — all of which would have the potential to scramble party lines and realign the political climate in his favor.

He could pass a Drain The Swamp Act, banning stock trading for members of Congress, which 86% of the country supports. And a Make America Healthy Act on food safety (which 80% of Americans want the government to address), doing things like banning food dyes (backed by 74% support). He could resurrect last year’s bipartisan tax deal as his long-sought Cut Cut Cut Act, simultaneously cutting corporate taxes and expanding the Child Tax Credit, with proposal to eliminate taxes on tips added to the mix.

Executive actions on immigration will only take him so far: a bipartisan Secure The Border Act, boosting funding for immigration enforcement (which 82% say is a “high” or “moderate” priority) while also protecting “Dreamers” (which 74% support) would be much more effective. An End the Ceiling Act could abolish the debt ceiling forever, as both Trump and Democrats have suggested, perhaps in exchange for spending cuts. As he teased yesterday, a Fix the Skies Act focused on aviation reform could reassure America after last week’s deadly plane crash.

And, of course, a DOGE Act could round out the agenda, with bipartisan reforms to encourage government efficiency, accountability, and transparency. (Maybe he could even make DOGE into an *actual* Cabinet department while he’s at it, expanding the existing Government Accountability Office into a more empowered national auditor to cut government waste, another highly popular priority.)

None of this is particularly likely. But it would all be in line with Trump’s agenda, popular among Americans, and more effective than any executive actions he could take on these issues. It would be populist and popularist. And Trump — having dominated the Republican Party and (until last week) scared the Democratic Party — entered office in January uniquely suited to make them into law. Packaged in the right way, they could be received as huge wins for his base, while also winning over voters in the middle.

Perhaps Democrats wouldn’t have gone for them — but what would it have looked like if these were the initial efforts Trump mounted, with congressional Republicans putting these sorts of bills on the floor, daring Democrats to vote against them? That’s what a president, and a party, interested in a lasting governing majority would try to do.

But there’s that pesky personality again, obsessed with revenge, even when it isn’t in his own best interest. We now seem to be hurtling towards the very opposite of this sort of bipartisan blitz, with a potential government shutdown looming amid Democratic hesitance to strike a spending deal if Trump might just refuse to spend the funds agreed on.

To the extent Trump is trying to legislate, he — like many of his predecessors, at least initially — is trying to do so along party lines. But, just as he found in his first term, this will be exceptionally difficult to accomplish, with his party divided on several grounds. Perhaps he will succeed; perhaps, as has happened to other presidents, he will fail and then start looking to the minority party for votes, which is often necessary to help presidents get their priorities across the finish line.

Sure, in the highly charged climate Trump has helped create, the two parties working across party lines to achieve broadly supported legislation still sounds like a fantasy. But, as a wise president once said, “that’s what the country’s about, really, isn’t it?”

I simply despise the current republican regime because they lack character and bravery. My father was a Lt. instructor pilot in the South Pacific, contracted malaria and then as a result of the malaria, arthritis of the spine, during WW2 . His brother William Bealke received the silver star from Patton while on duty in France for bravery. I am relieved they are not alive today to see this narcissistic, pathological liar lead us down a despicable and destructive path. Policy differences are acceptable but lack of character and a lack of empathy are not, and if we do not find away out of this current disaster we are in danger that will have lasting repercussions. I never thought we would come to this and I am happy to say I can look my grandchildren in the eye having never voted for Trump

One very frightening possibility, which doesn't seem to have entered your analysis lately, is that Trump isn't interested in long lasting legislation because he intends to get rid of the legislative branch. There was already a bill to allow Trump a third term- I don't think right now that that's possible, but it does look like the groundwork is being laid for Trump to be able to cement his legacy by doing away with, or at least severely limiting elections. The current plan to require voters names on their IDs to match their birth certificates already disenfranchises a lot of women. Hopefully you are right, and none of this sticks for more than four years, but I think that if we aren't at least considering the possibility that it will stick, we might be blindsided later.