Why It’s Pointless to Guess at Biden’s Legacy

Most presidents don’t have one, and that’s OK.

When Joe Biden sat behind the Resolute Desk last night, he joined a proud tradition of presidents delivering farewell addresses at the end of their time in the White House.

There’s George Washington, whose farewell address — containing prescient warnings about the dangers of partisanship — is so resonant that it’s read aloud on the floor of the Senate every year. There’s Dwight Eisenhower, whose valedictory speech is a cherished example of a president bravely taking on his own allies (in his case, inveighing against the “military industrial complex” as a celebrated former general).

There’s—um, I guess that’s it actually?

If you can remember the contents of other final presidential speeches, congratulations. (Recalling the mere fact that Obama gave one in Chicago, or that Trump gave one under pressure, doesn’t count.) But it’s striking to think of how many presidential farewells — presumably the one speech presidents tailor, above all others, to cement their legacies and be remembered by the sweep of history — quickly fade to dust.

The other day, I went in search of some of these forgotten farewells; specifically, I wanted to read Benjamin Harrison’s final Annual Message, read aloud to Congress on his behalf by the House Clerk. Today, we’d call that a “State of the Union,” not a farewell address — but, regardless, it was his last major message to the American people, penned in December 1892, one month after he’d been defeated for re-election, knowing that his time in office was running short.

I wanted to read Harrison’s address because I’ve been trying to decide how Joe Biden will be remembered by history. And Harrison — the only other president whose time in office was bracketed by a single person (he entered office by beating incumbent Grover Cleveland, who then returned the favor four years later) — seemed like as good a place as any to start.

I. Defensive much?

Harrison’s message is much more technical than presidential farewell addresses (or State of the Union speeches) are today, but I was surprised to find essentially the same broad strokes as Biden touched on in his address last night.

Right off the bat, Harrison seemed intent on informing his audience that, actually, he was leaving his predecessor-turned-successor a strong economy, no matter what you may have heard.

“In submitting my annual message to Congress,” Harrison began, “I have great satisfaction in being able to say that the general conditions affecting the commercial and industrial interests of the United States are in the highest degree favorable.”

He continued:

A comparison of the existing conditions with those of the most favored period in the history of the country will, I believe, show that so high a degree of prosperity and so general a diffusion of the comforts of life were never before enjoyed by our people.

The total wealth of the country in 1860 was $16,159,616,068. In 1890 it amounted to $62,610,000,000, an increase of 287 per cent.

The total mileage of railways in the United States in 1860 was 30,626. In 1890 it was 167,741, an increase of 448 per cent; and it is estimated that there will be about 4,000 miles of track added by the close of the year 1892.

The official returns of the Eleventh Census and those of the Tenth Census for seventy-five leading cities furnish the basis for the following comparisons: In 1880 the capital invested in manufacturing was $1,232,839,670. In 1890 the capital invested in manufacturing was $2,900,735,884.

He goes on to list many more statistics, but you get the point: according to Benjamin Harrison, the Benjamin Harrison economy was much better than the one he inherited, in no small part because of infrastructure built and manufacturing invested in.

“There never has been a time in our history when work was so abundant or when wages were as high, whether measured by the currency in which they are paid or by their power to supply the necessaries and comforts of life,” the outgoing president announced.

You know what’s coming next. Here’s Joe Biden last night:

Instead of losing their jobs to an economic crisis that we inherited, millions of Americans now have the dignity of work. Millions of entrepreneurs and companies, creating new businesses and industries, hiring American workers, using American products. And together, we have launched a new era of American possibilities: one of the greatest modernizations of infrastructure in our entire history, from new roads, bridges, clean water, affordable high-speed internet for every American.

Harrison made sure to touch on the legislation he churned out — although, ironically, the specific policy (a major tariff bill) is much more in President-elect Donald Trump’s wheelhouse than Biden’s — and the state of foreign policy. “Our relations with other nations are now undisturbed by any serious controversy,” Harrison announced.

Over to Biden:

We [meaning, I assume, the United States, not the Biden administration] invented the semiconductor, smaller than the tip of my little finger, and now is bringing those chip factories and those jobs back to America where they belong, creating thousands of jobs. Finally giving Medicare the power to negotiate lower prescription drug prices for millions of seniors. And finally doing something to protect our children and our families by passing the most significant gun safety law in 30 years. … Overseas, we have strengthened NATO. Ukraine is still free. And we’ve pulled ahead in our competition with China. And so much more.

No farewell address would be complete without a sage warning from an elder statesman about a problem plaguing the country. Harrison offered two. He closed his speech by calling for legislation to prevent “the frequent lynching of colored people,” and for an election reform package that would address the “evils” of gerrymandering, in order to “free our legislation and our election methods from everything that tends to impair the public confidence in the announced result.”

Biden, meanwhile, took a page from Eisenhower’s book, decrying the “potential rise of a tech-industrial complex” and warning that an “oligarchy is taking shape in America of extreme wealth, power, and influence.” Biden, like Harrison, also touched on a litany of other threats to democracy, calling for a reform package to address them. Some things never change.

Proud of what they had accomplished, both closed on an optimistic note. “The America of our dreams is always closer than we think,” Biden said. “And it’s up to us to make our dreams come true.” Or, as Harrison put it: “There are no near frontiers to our possible development. Retrogression would be a crime.”

II. The eyes of history

Will Joe Biden win the historical battle to define his presidency? Well, did Benjamin Harrison?

In doing some research on the 23rd president, I was surprised, frankly, to see more positive assessments of Harrison than I had expected. “His administration functioned efficiently, faced tough issues decisively, and proved remarkably productive,” the historian Allan Spetter has written. He ushered several pieces of landmark legislation to passage: the McKinley Tariff, the greatest act of protectionism in the country’s history; the Sherman Antitrust Act, which is still the legal basis the government uses to fight monopolies today.

“No president since Lincoln pursued a more active foreign agenda than Benjamin Harrison,” Spetter also says. He convened the first Pan-American Conference with the U.S.’ trading allies; he “launched the nation on the road to empire” by pushing for the annexation of Hawaii.

Historians also praise his efforts on behalf of civil rights: he appointed Frederick Douglass as his envoy to Haiti (although Douglass later resigned when Harrison’s imperial intentions became clear); in addition to the lynching bill, he also fought (unsuccessfully) for legislation that would have ensured Black enfranchisement in the South, seven decades before that goal was realized.

Of course, none of it was enough to win re-election when former President Cleveland came knocking, looking for a rematch. Harrison, known as the “Human Iceberg,” was not a particularly effective speaker. Critics alleged that he was a mere puppet for more powerful members of his party, including his more popular secretary of state, James Blaine. And, not unlike Biden’s 2021 stimulus package, his most influential economic legislation — the McKinley Tariff — ended up backfiring, sparking a steep increase in prices. Americans did not end up being persuaded by Harrison’s rosy assessment of his economic stewardship, no matter how many statistics he flung at them in his farewell.

Did he manage to persuade history? Well, I don’t know, let me ask you: what do you remember about Benjamin Harrison’s handling of the economy? Yeah, that’s what I thought. Some of his legacies live on, but none are particularly attached to him. (It’s striking that his two most influential pieces of legislation bear other people’s names: future President William McKinley for the tariffs; Sen. John Sherman for antitrust. I, for one, knew about both bills. I didn’t know either were signed by Harrison.) The robust defense offered in his farewell address wasn’t so much accepted or rejected. It was forgotten.

I’m sure a comparison to Benjamin Harrison isn’t exactly the historical legacy Joe Biden (he of the oft-referred-to “FDR-sized presidency”) wanted.

But, honestly, couldn’t you do worse than Harrison? A productive stream of legislation? No U.S. troops sent to foreign war zones? Ahead of his time on civil rights?

Of course, there’s just one thing: nobody remembers him — and if they do, it’s probably as the fixin’s to the Grover Cleveland sandwich. Biden, I’m confident, will not want his legacy to be defined by the man who came before and after him.

But if it’s any consolation to Biden, it’s not like Cleveland’s modern name ID is much higher than our friend Harrison’s. I know, I know: it feels absurd to think a future era might not remember Donald Trump, who has dominated every minute of our politics for the last nine years.

Then again, Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland ran this country for a combined twelve years. They were major figures of their time: in comparison to each other, as two-time rivals, and on their own terms. How much can you tell me about either, not even two Jimmy-Carter-lifetimes after the fact?

III. Public perceptions are sticky

While we’re at it, what do you have to say about the Biden legacy? Pollsters have been asking that question a lot lately, and — spoiler alert — the early reviews, they are not pretty.

A recent Gallup poll found that 54% of U.S. adults believe that Biden’s presidency will be remembered as “poor” (37%) or “below average” (17%). Only 19% think he’ll be seen as “above average” (13%) or “outstanding” (6%). The remaining 26% judge his likely legacy as “average.” (Even among Democrats, “average” is the plurality response. Only 12% think this longtime leader of their party will go down in history as “outstanding.”)

Similarly, in a new AP/NORC poll, only 25% of adults said Biden’s presidency was “great” (6%) or even “good” (19%). Compare that to the 47% who call his tenure “poor” (16%) or “terrible” (31%). (This time, “average” came in at 28%).

A CNN poll, meanwhile, recorded Biden leaving office tied for his lowest approval rating of his term: 36%. For most of his presidency, his favorability rating (a measure of how many Americans like Biden personally, as opposed to how many think he is doing a good job as president) remained higher than his job approval, a vestigial sign of Biden’s decades-long relationship with the American people, even as his presidency floundered.

No longer. Per CNN, Biden will leave office with his favorability rating even lower: only 33% have warm feelings about the departing commander-in-chief.

How often do presidential approval ratings at the end of their term end up predicting how future Americans, and future historians, will judge them?

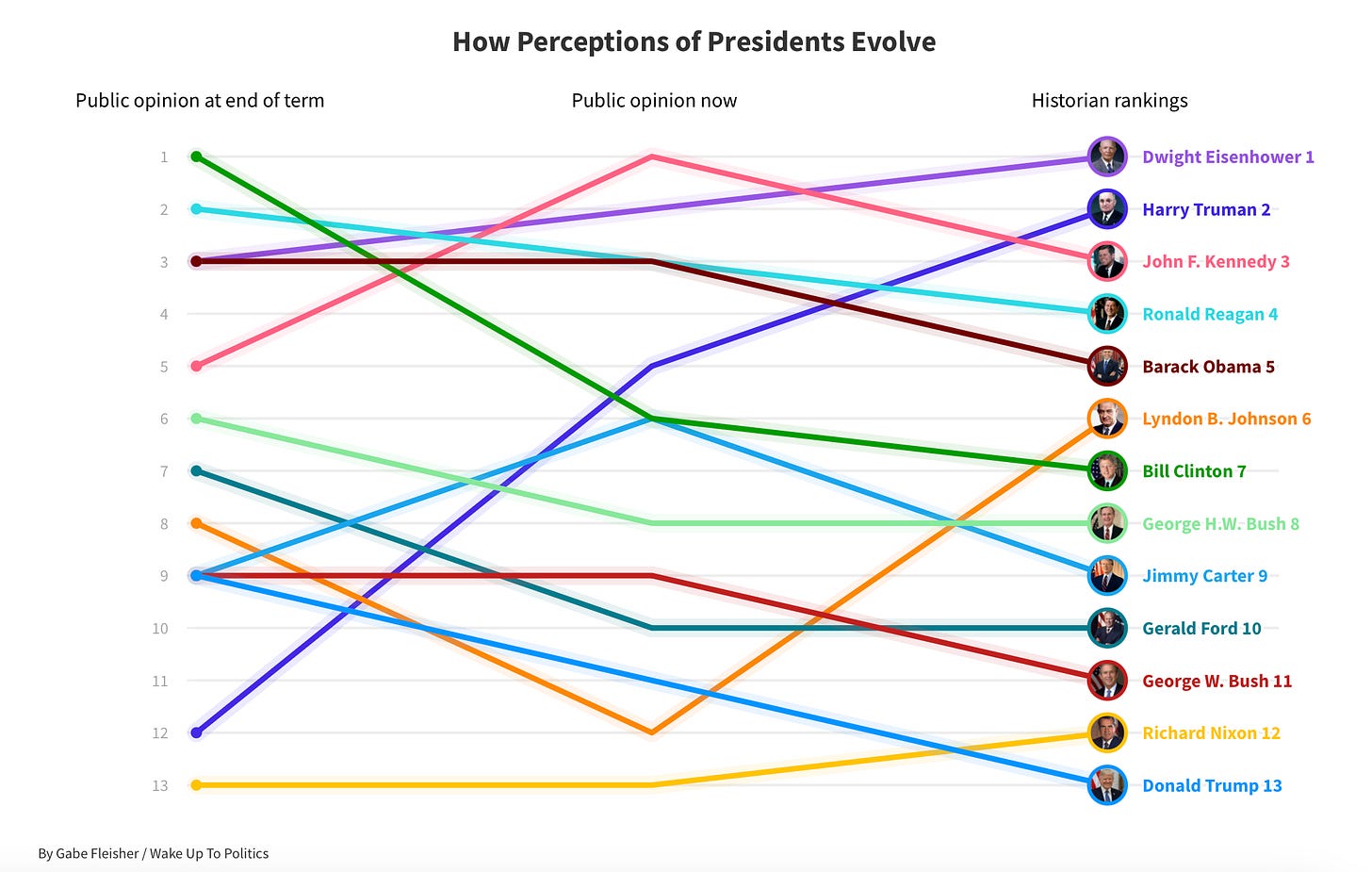

I ran the numbers, using Gallup’s final reading of public opinion at the end of each president’s term (dating back to the advent of Gallup); a YouGov poll from 2021 on presidential popularity today; and then C-SPAN’s 2021 rankings by presidential historians. I then ordered each president according to how the rank by each metric amongst themselves.

Here it is as a fun animation:

And here it is by itself:

The three metrics are somewhat more correlated than I might have expected. Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and Barack Obama were popular when they left office, popular now, and popular among historians. (The orders differ — Americans c. 2021 love JFK — but they’re all up at the top.)

On the bottom half of the list, Richard Nixon, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump were unpopular, unpopular now, and judged harshly by historians. (In order to use a standard dataset, this measure of Trump’s current popularity predates the bump in public opinion he has received after his re-election. Still, while notable, it is not big enough to meaningfully change his ranking.)

And then there’s the “averages”: presidents like Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, and George H.W. Bush, of whom opinions have remained constant in their own way — mediocre then, mediocre now, mediocre according to the experts.

Who have I left out? Out of the last 13 presidents, public or scholarly opinions have only really changed on three since they left office. Harry Truman has skyrocketed up the list, from the second-worst approval rating when he left office (a dismal 32%) to the second-best rating from historians. In tandem, the public also views him much more warmly: he receives a 51% favorable rating today. (Which comes first: historians re-assessing someone, or the public? It’s a chicken-and-egg conundrum, but clearly the two metrics interact with one another.)

Lyndon Johnson, too, has seen a rebound: he left office on the less popular side, mostly remembered for the issue of the day (Vietnam). Now, he is more remembered for his impressive legislative record, including the Civil Rights Act and the Great Society. Historians judge him fairly highly. Notably, though, this is a case where that hasn’t translated to a shift in public opinion: his favorability rating sits at 37%. (Biden, who has also sought to compare his legislative record to LBJ’s, may want to take note.)

Finally, there’s Bill Clinton, who left office more popular than any president since World War II, boasting a booming 66% approval rating. Whether because of the glare of the #MeToo era, backlash to neoliberalism, or politicization tied to his wife, the American people are much less fond of him now (45% favorable); historians similarly place him in the middle, not top, of the heap.

At first glance, that doesn’t bode well for Biden: public opinion at the end of one’s term is usually roughly consistent with how presidents are viewed in the subsequent decades. Then again, this is taking the short view. The above analysis only takes into account the last 13 commanders-in-chief, aka the ones we remember.

And thus, we arrive at the dirty truth of presidential legacies: most presidents don’t have one.

Most of these men — even the ones we think of as political giants of our day — are fated to end up the dustbin of history before long. Foolish is the presidential legacy-watcher who forgets the lessons of Mr. Cleveland and Mr. Harrison, those two forgotten party leaders.

IV. Can you count to 46?

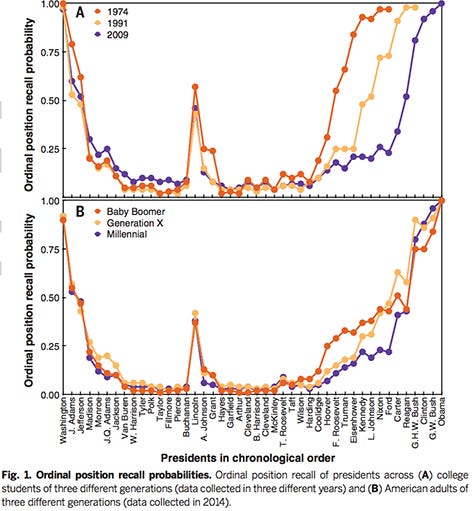

In case you don’t believe me, this has been studied! Dr. Henry Roediger, a human memory expert at Washington University in St. Louis, has now given the same test to three generations of college students (in 1974, 1991, and 2009). He gives them a blank piece of paper with a numbered list, and asks them to write down the names of as many presidents as they can remember, in order. (If they don’t know the order, they are told to put the president’s name on the side.) In 2014, he conducted a similar test for adults.

Here are his results:

Essentially, to be remembered as a U.S. president, you have to need to do one of three things:

Be one of the first presidents

Be one of the most recent presidents

Be Abraham Lincoln

Other than that, the picture isn’t pretty for presidents in the popular memory. (Between Martin Van Buren and Theodore Roosevelt, there is a near-century gap of presidential history where only the “Great Emancipator” stands out.) The amazing thing about this chart is how you can see, over three generations, how quickly presidents fade.

Presidents like Franklin Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower were still relatively fresh in students’ minds in the 1970s (the orange line in the top chart). By the 1990s (the yellow line), each had dropped dramatically. By 2009, fewer than a quarter of students named any of them.

Roediger says, as a general rule, most presidents are forgotten within 50-to-100 years of leaving office. “By the year 2060,” he has predicted, “Americans will probably remember as much about the 39th and 40th presidents, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, as they now remember about our 13th president, [redacted: do you know?]”1

V. The Klosterman Rule

And so we return to where we started: how will Joe Biden rank in all this?

Discussing this question recently with the wise Matt Glassman, he pointed me to the thought-provoking book, “But What If We’re Wrong?: Thinking About the Present As If It Were the Past” by the essayist Chuck Klosterman.

The book is obsessed with the idea that when we try to guess how the future will perceive the present day, we are almost always wrong. Like, really wrong — in big and humorous ways.

One of the concepts that Klosterman proposes is that, in the historical memory, everything eventually gets boiled down to One Big Thing (or person).

Quick: name a composer of military marches.2 Quick: name an architect.3

“There’s a basic human reason for this simplification,” the author Alex Ross tells Klosterman. “It’s difficult to cope with the infinite variety of the past, and so we apply filters, and we settle on a few famous names.” Or, usually, one name. Klosterman’s is a winner-take-all theory of memory.

Two things are important here: a) we’re really bad at guessing who that one name will be (Melville, Dickinson, and Kafka are all examples of writers who our seen as defining eras or genres now but were mostly unknown in their lives) and b) once that name is decided, our memories are retrofitted so that the story of that era revolves around that person or theme, even if that leads to radical shifts away from how that era was understood at the time. (What we admire about 20th-century architecture is now whatever Wright did, since he’s our One Big Architect, putting aside the other schools of thought that loomed large at the time. Klosterman also proposes that if the debate over transgender rights is remembered as a major theme of our time, the movie The Matrix — directed by two filmmakers who later came out as trans — will be seen as symbolic of that theme, even though that is very much not how the movie was understood when it came out.)

Eventually, this will be true for our era.

Quick: name One Big Thing about the 2020s.

That one was a trick question. We can’t possibly know yet. As I sit here today, my best guess is that Donald Trump will be the defining figure of this decade, which would mean — if Klosterman is right — that any opinions about Joe Biden and other 2020s-era politicians will revolve around opinions of Trump (slash Trumpism slash global populism).

If Trump is remembered as a uniquely, epochally bad president, then Biden will probably start to look better over time, since he was the main figure in tension to Trump in our era (without any regard to whether or not he helped deliver Trump a second term. Such nuances will likely fall away: if Trump bad, Biden good. Or, perhaps more likely, if Trump is regarded poorly, Barack Obama — who obviously has a better case for making it into the history books — will be remembered as his historical rival, even though the two never actually ran against each other.)

On the other hand, if Trump is regarded by history as a successful president — and, as I noted yesterday, he does enter with a fairly strong hand (although, granted, also with a history of messing things up for himself) — then Biden, as his opposite, will be remembered as a failure.

But what if I’m wrong?

Maybe the 2020s will be defined by AI. In that case, Biden’s presidency might be retroactively remembered as either a key stepping-stone to our artificial intelligence future, or a missed opportunity to advance earlier, even though AI is not presently seen as a major part of the Biden legacy. (Although, notably, it was a recurring theme in his farewell address.)

Maybe the decade will be defined by political violence. In that case, his opposition to January 6th might rise to the top, or his failure to punish Trump for it. (This assumes, to be fair, that political violence is looked at unfavorably by our descendants.) Maybe the decade will be defined by race, in which case Biden’s legacy could be dominated by his time as vice president to Obama, as well as his own choice of vice president. Or maybe the decade will be defined by selfish political leaders, in which case his initial refusal to step aside and his pardon for his son will be the dominant legacies. Or maybe we’ll remember the 2020s as a time of peak dysfunction, in which case we’ll either look at Biden’s presidency as a critical example (because he didn’t get so many of his proposals passed!) or an exception (because he got so many of his proposals passed!) These two ideas are flat-out contradictions of each other, but it is difficult to assume right now which one historians will adopt as fact.

Or maybe the decade won’t be remembered much at all, like the decades after Lincoln — the Cleveland and Harrison decades! — about which most Americans would likely draw a blank if you asked for a discussion of them.

The point here is that most decades are only remembered by One Big Thing (at best!), which means presidencies are (at best!) remembered for One Medium-Sized Thing they contributed that historians can conveniently fit within the story of the One Big Thing.

And we don’t know what the One Big Thing will be yet.4

Which is why assessments of Joe Biden’s legacy — including, I guess, the one you just dedicated so much time to read — are ultimately a pointless exercise. Every one I’ve seen has thrown out a million different facets of his presidency that future Americans will surely balance against each other: Infrastructure! CHIPS! Ukraine! Gaza! Pardons! Debates! Oh my!

But you, dear reader, know better. And so does Benjamin Harrison.

It’s Millard Fillmore.

Was it John Philip Sousa?

Was it Frank Lloyd Wright?

In the short-term, Biden did himself no favors by pursuing so many conflicting priorities as president (refusing to choose One Big Thing for history to remember him by), as Dylan Matthews ably chronicled in his recent piece, “The president who could not choose.” (As one example, the dominant theme of Biden’s farewell address — oligarchy — was an entirely new theme for his presidency added at the last minute, as he has only used the phrase two other times during his tenure. Then again, Eisenhower never said the phrase “military-industrial complex” until his last speech either, and now it’s overshadowed almost anything else he did or said as president.)

Either way, Biden’s inability to choose shouldn’t matter much in the long-run. History will choose a Big Thing for him, whether he likes it or not. (Or, history won’t, and his presidency will be forgotten.) All the different priorities will be flattened into one eventually.

Another major (and important) criticism of Biden — the fact that so many of his programs are taking so long to implement — shouldn’t necessarily matter either. A lot of Great Society programs only became important after the fact. But it is important that, in that case, they can easily be bundled into a broader legislative effort to be remembered as a shorthand, which is then tied back to LBJ’s. Biden’s packages lack that, at least for now. That runs the risk that, even if Americans do eventually appreciate programs like Medicare drug price negotiations down the line, they never get tied back in the popular memory to Biden, just as no one associates the Sherman Antitrust Act with McKinley. (From this lens, Republicans naming the Affordable Care Act as “Obamacare” seems like perhaps the greatest favor a political party has ever done to their opposition, since — if Obamacare is, in fact, remembered by history, it will be difficult to forget who passed it.)

However, one criticism of Biden’s will hurt his legacy: the fact that so many of his programs, largely for reasons Matthews lays out, were temporary. He gambled that they would be so beloved that they would be extended. He gambled wrong, and as a result, it’s unlikely Americans in, say, 2060 will have much of a memory of programs that were only in effect from 2021-25 (or, in some cases, from 2021-22).

Every morning I do 47 bench presses after my bike ride or walk. And with each raising of the barbell, I name the correct President in sequence. At age 74 (today being my birthday), it helps keep me mentally active. Thanks for this interesting comparison of Benjamin Harrison and Joe Biden.

Wow Gabe- thanks for sharing all of this fascinating research! One thought on the “ one big thing” for future historians about our times. I have begun to date events in my own life as “before pandemic” and “ after pandemic.” Does anyone else do this? I wonder if that may be history’s turning point, in which case Biden may rise in their assessments due to his success helping the country recover from the mismanagement and chaos of his predecessor…