Why It Matters That There’s No Trump Doctrine

Without consistent principles to pass on, Trump’s impact after he leaves office might be smaller than we think.

Good morning! It’s January 13, 2026. There’s a lot going on right now:

A number of Republican lawmakers are defending Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell after news broke that the Justice Department is investigating him. Also, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is reportedly upset about the probe, worried about how it could impact financial markets.

The U.S. reportedly used a secret aircraft painted to look like a civilian plane in its first attack on an alleged drug boat in the Caribbean, which would be a war crime.

Minnesota is suing the Trump administration in an attempt to block the deployment of thousands of immigration agents to the state.

Arizona Sen. Mark Kelly is suing Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth over the Pentagon’s effort to demote his Navy rank after he participated in a video urging service members not to comply with illegal orders.

Former Rep. Mary Peltola announced a bid for Senate in Alaska, a major boost to Democrats’ long-shot hopes of winning back the chamber this year.

The Supreme Court is set to hear oral arguments this morning on state laws requiring student athletes to play on the teams that match their birth sex. I’ll be inside the courtroom, so check back tomorrow for a full download on that.

But here’s what’s on my mind today…

We are now 10 days removed from U.S. troops parachuting into Venezuela and capturing the country’s leader, Nicolás Maduro. For such a dramatic act, not much has changed in the time since.

Are things better for the Venezuelan people? The (illegitimate, according to the United States) Maduro regime is still in charge, sans Maduro himself. Repression has only intensified, according to the New York Times, as the U.S.-backed government led by interim president Delcy Rodríguez (Maduro’s former deputy) has “interrogated people at checkpoints, boarded public buses and searched passengers’ phones, looking for evidence” that they supported Maduro’s capture.

The Venezuelan government claimed to have released 116 political prisoners on Monday, but rights groups say only 41 have actually been released, with 800 more political prisoners remaining behind bars. A major prison that Trump said would be closing, which he referred to as a “torture chamber,” remains open. No plans for elections or democratization appear to be on the horizon, although perhaps that will change after Trump meets with opposition leader María Corina Machado on Thursday. (Machado has said she might give Trump her Nobel Peace Prize, although the Nobel Committee poured cold water on the idea.)

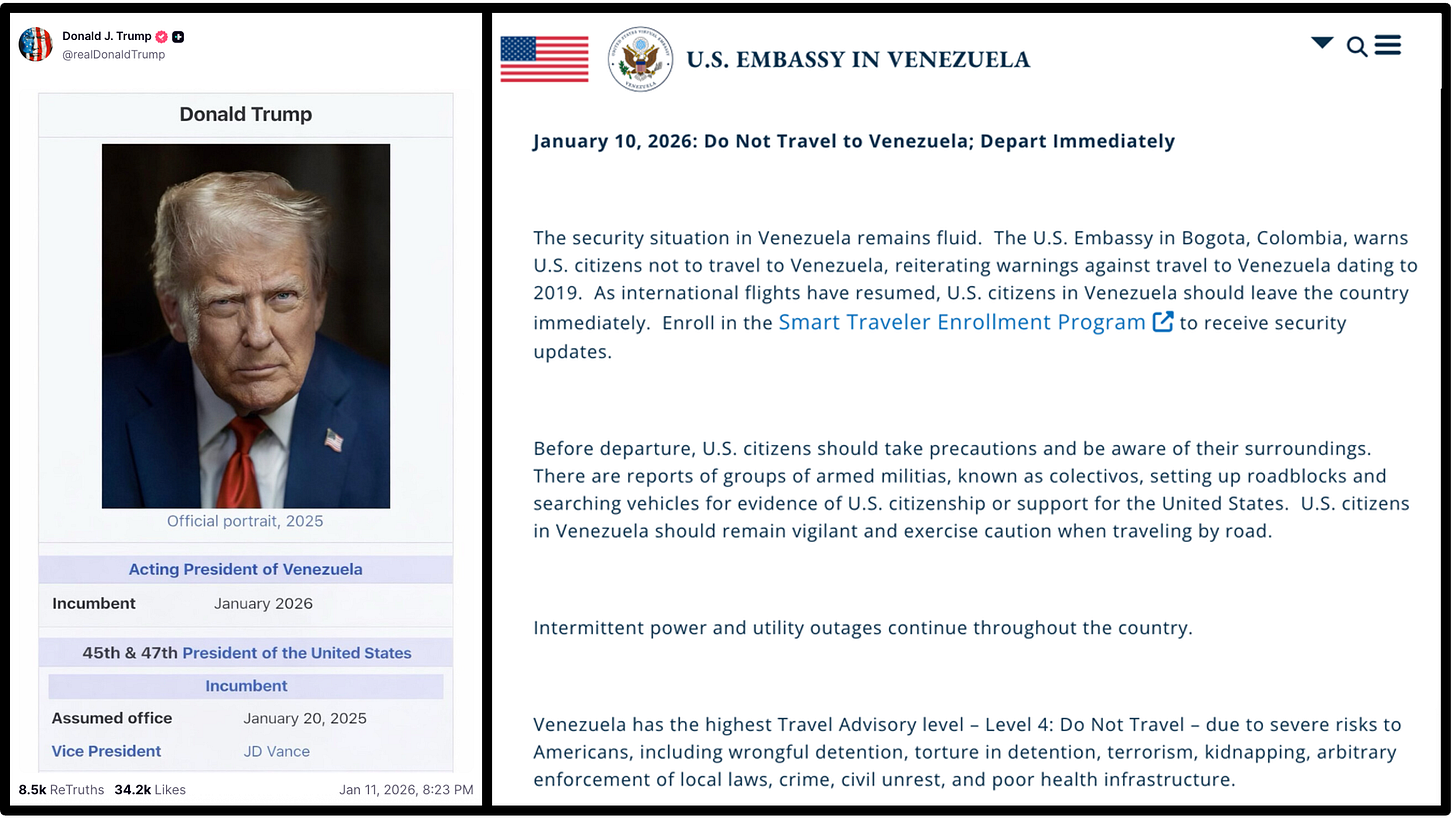

Are things better for the United States? On the ground, seemingly no. The State Department put out a warning this weekend telling U.S. citizens in Venezuela to “leave the country immediately,” due to reports that armed paramilitaries are “setting up roadblocks and searching vehicles for evidence of U.S. citizenship or support for the United States.” (The groups have apparently been empowered by Rodríguez to do so.)

That travel guidance came one day before Trump posted a graphic on Truth Social identifying himself as “Acting President of Venezuela.” It is somewhat odd to see, in the span of a single weekend, messages that say Trump is running both the U.S. and Venezuela, but also that citizens of the former should “Depart Immediately” from the latter due to “risk of wrongful detention, torture in detention, terrorism, kidnapping, arbitrary enforcement of local laws, crime, civil unrest, and poor health infrastructure.” The U.S. government must be furious at Venezuela’s Acting President about all that! Oh wait…

What about underneath the ground, where Trump’s true ambitions seem to lie? Trump said last week that Venezuela will turn over 30 million to 50 million barrels of oil to the U.S., though the Venezuelan authorities have yet to provide confirmation of that. Meanwhile, American companies appear reluctant to enter Venezuela, considering the shaky political situation. “We’ve had our assets seized there twice, and so you can imagine to re-enter a third time would require some pretty significant changes,” the CEO of Exxon Mobil said at a White House meeting last week. “Today it’s un-investable.” (Trump responded by saying, “I’ll probably be inclined to keep Exxon out.”) Even if Trump’s dream of the U.S. dipping into Venezuela’s oil reserves does come true, it could take up to a decade and $100 billion to achieve — an investment that might not be very worthwhile either for the companies (which may be pivoting to clean energy by then) or the U.S. (which is already the world’s top oil producer).

Last week, in my first piece after the Maduro capture, I argued that there is no Trump doctrine and that the president didn’t seem to have concrete plans about what to do next in Venezuela or how to adopt his new approach around the world. That remains true after 10 days.

Today, I want to talk about what that means, for the present and the future — why it matters that there’s no Trump doctrine — but first, let’s briefly discuss if I’m right that there isn’t one.

I.

After my initial piece, Matt Glassman — one of the clearest thinkers and writers around, whose Substack you should all subscribe to — disagreed with me that there’s no Trump doctrine. Matt wrote:

I disagree with the notion that there’s no Trump doctrine. It seems more or less obvious to me that Trump: (1) views the world as led by great powers led by great leaders; (2) great powers need to be respected; (3) lesser powers can and should be exploited, and if you instead ally with them you are a sucker missing an opportunity and not a great leader; (4) everything is zero sum. This leads to a basic foreign policy of (1) unwinding American international commitment with weak powers; (2) expanding our influence locally in the western Hemisphere; and (3) staying out of the way of other great powers in their spheres of influence.

I have a lot of respect for Matt, and this is one of the better distillations of a potential Trump doctrine that I’ve seen. If there is a Trump doctrine, in other words, then I agree that this would probably be it.

But I’m still not convinced.

Trump is clearly much more sympathetic to the great-powers view of the world, and much less sympathetic to smaller American allies, than any of our recent presidents. But I wouldn’t say that he is “staying out of the way of other great powers in their spheres of influence.” Trump’s support for Ukraine, for example, has obviously been very inconsistent, but I wouldn’t say that Trump’s overall position has been to simply let Russia work its will: at various points, he has urged Ukraine to “take back their Country in its original form” and “maybe even go further than that,” sold U.S.-made weapons to NATO allies so they can be provided to Ukraine, and last week his administration made a vow to defend the country if Russia attacks again as part of a peace proposal.

Regardless of how much support he has actually given Ukraine, Trump clearly wants to promote the message that he has been critical to the country’s success: “You know, if I didn’t give them those Javelins, this war would have been over immediately,” he told the New York Times last week, sounding proud to have intervened in Russia’s sphere of influence, rather than determined to stay out of it. In fact, Trump told the Times, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has “only got one thing” going for him: “Donald Trump.”

Then again, of course, at other points he has sounded much more skeptical of Ukraine. But that’s why I said that there’s no Trump doctrine, no undergirding philosophy that dictates Trump’s intervention in another country or lack thereof. Some days (though not as much lately), Trump sounds like a true isolationist, prepared to burrow into the U.S. and ignore other parts of the globe. Other days, he seems like he wants to be president of the world — controlling events not just in America or its “sphere of influence,” but far outside those borders as well.

Steve Bannon and other anti-interventionist figures in Trump’s orbit have recently been defending his Venezuela adventurism by citing a Western Hemisphere exception to Trumpian isolationism. I am very skeptical that this is anything more than an attempt to stay on Trump’s good side while still retroactively insisting that his most recent actions fit into their philosophy, seeing as Bannon never appears to have mentioned such an exception before 2025 and Trump does not seem to be confining himself to just one hemisphere, both in Russia/Ukraine and in the Middle East.

Trump is currently considering a(nother) military strike against Iran, which is not in the Western Hemisphere, in response to the hundreds of people killed in protests there. Trump and Bannon have spent years scorning the idea of regime change in the Middle East, before Trump openly embraced the concept with respect to Iran after the U.S. bombing in June.

Once again, there is no consistency, only what Trump has in his head at a given moment. When the Times asked Trump if there were any limits on his global power, he responded: “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me, and that’s very good.”

II.

The ultimate test of whether Trump adheres to a spheres-of-influence philosophy would be to see if he stepped up to defend Taiwan if it were ever invaded by China.

In the Times interview, Trump certainly sounded like he was prepared to view the island as part of China’s sphere of influence: “Well, it’s a source of pride for him,” Trump said, referring to Chinese president Xi Jinping. “He considers it to be a part of China, and that’s up to him, what he’s going to be doing.” But he also made clear that he would oppose a Taiwan invasion and, perhaps more importantly, that he would view it as a personal affront: “I’ve expressed to him that I would be very unhappy if he did that, and I don’t think he’ll do that. I hope he doesn’t do that… He may do it after we have a different president, but I don’t think he’s going to do it with me.”

To be clear, I am by no means saying I am confident that Trump would do much to defend Taiwan in the face of a Chinese invasion. But I am also by no means confident that he wouldn’t want to defend Taiwan in the face of a Chinese invasion, which is what the sphere-of-influence doctrine would suggest. I simply don’t think there’s a clear answer, because Trump governs with a non-ideological spontaneity that can’t really be boiled down to a doctrine.

This is the first reason why it matters that there’s no Trump doctrine: it means we have very little idea what Trump might do next. The goal with a doctrine is to give American citizens and global leaders some idea of a rule for how a president views use of the force or America’s role on the world stage: if X happens, then America will do Y, whether X is Europe impinging on the Western Hemisphere (as in the Monroe Doctrine) or a country potentially tipping towards communism (as in the Truman Doctrine).

Here, if the Trump Doctrine was to remain involved in the Western Hemisphere and butt out everywhere else, if X was China invading Taiwan, then Y would be the U.S. staying out of it. But I can’t say I’m that confident that Trump would hew to such a rule.

Of course, he would say this is a good thing, that previous presidents have been too willing to forecast their plans in advance, that unpredictability is a benefit (see: the Madman Theory), and maybe he is right. (Conversely, in the case of Taiwan, Trump can credibly say that his lack of clarity is merely following in his predecessors’ footsteps: since the 1970s, U.S. policy towards Taiwan has literally been called “strategic ambiguity,” after all.)

Either way, for good or for ill, the lack of a Trump Doctrine means we have very little insight into what Trump will do next on any given topic. Will he invade Greenland? Will he strike Iran? Would he defend Taiwan? We don’t know. If we had a doctrine, we would also know what the X was that drove Trump’s policymaking, which means we would know his goals for Venezuela: for example, if the variable that dictated intervention was “if Latin American countries fall into dictatorship,” then we would know Trump plans to install democracy in Venezuela. But we have limited insight into why Trump went into Venezuela, because he has not laid out a broader standard applicable there or elsewhere, so we don’t really know what the U.S.’ plans are there.

That’s reason number one why it matters that there’s no Trump doctrine: it clouds the present, and the near-term future (Trump’s actions for the rest of his second term).

III.

What about what comes after Trump? Here’s the second reason Trump’s impossible-to-define foreign policy matters.

Trump is often described as not just a party leader but a movement leader, following in the footsteps of transformational presidents like Ronald Reagan or Barack Obama who seem to be commanding their own set of devoted followers, not just normal partisans.

I think this accurately captures Trump’s relationship with his voters, but the one respect in which it fails is that a movement suggests something more lasting than one person. But what will Trumpism, as a movement, mean once Trump has left the stage?

I was thinking about this last week, after Trump went positively nuclear on the five Republican senators who voted to advance a resolution prohibiting Trump from sending troops into Venezuela, writing on Truth Social that they “should never be elected to office again” (and apparently underlining the message in private phone calls).

The truth is, though, this resolution sounds a lot like something Trump might have mocked Republican senators for opposing as recently as 2016, when he was trying to separate himself from the neoconservative wing of the GOP and saying things like, “The current strategy of toppling regimes with no plan for what to do in the day after only produces power vacuums that are filled simply by terrorists.”

There is simply no way to build a lasting political movement when its leader blasts lawmakers for supporting something that he probably would have upbraided them for opposing not so long ago. It’s like if Obama was elected in 2008 and then not only didn’t pass a health care bill, but actually mocked Democratic lawmakers for supporting one. Trump says that the contours of his philosophy exist in “my own mind,” and that has worked well enough while he is on the stage, since the isolationist and interventionist factions of the Republican Party generally both go along with whatever he wants to do.

But one day he will no longer be on the stage, and the lack of any concrete philosophy to pass on guarantees that those factions will instantly descend into intra-party warfare the minute Trump exits the stage, since will both start laying claim to his legacy (and his vagueness ensures that they will both credibly be able to do so). This means that Trump, as a name, will live on (since every side of the party will want to be seen as carrying on Trump’s mantle), but Trumpism, as a guiding philosophy, will not, since there is no guiding philosophy to speak of outside of the contents of one man’s mind.

This is counter to how presidents normally try to govern. We know what a Reaganesque approach to economics looks like, or a Carteresque approach to foreign policy. When they leave office, parties then try to either adopt or ditch those approaches, depending on whether they proved popular.

Oftentimes, support for a popular president does not prove to be transferrable to a handpicked successor (see: Barack Obama), but presidents at least aim for their policies, their political philosophy, their approach to governing, to live on, which is the whole point of explicating a doctrine or putting together a comprehensive policy platform (something else Trump has resisted).

What will Trumpism be once Trump isn’t there? Well, what’s a Trumpist approach to foreign policy? Or health care policy? Or abortion policy? No one really knows, so it will be impossible to pass on and try to use or replicate.

From this vantage point, it’s possible that Trump’s impact on American politics will be smaller than we currently imagine, as hard as it may be to believe now. But Trump’s personalist style, by definition, means that he isn’t really handing a guidebook to the next Republican president for how to govern, so even if his name lives on within the GOP, his won’t be a very effective guiding model. “What would Trump do?” will be an impossible questions for future Republicans to ask. While he’s on the scene, he’s won over the GOP, but there are very few positions that Trump has persuaded the party to in a lasting way, because he has no lasting positions (and those, like tariffs, that he does have boast minimal support within the party).

This means the minute Trump walks away, there will be all-out war to define Trumpism, and there will be no way to win it, since everyone will be wrong and everyone will be right. And there will be no set of Trumpist positions that continue to dominate the party: the party will have to redefine itself anew.

Trump’s legacy will likely be felt in other ways, like his style living on more than his policies, although — while there are ways this will certainly be true — it’s worth noting that his imitators have generally not found success in competitive elections while aping his style.

Does Trump care what the Republican Party looks like come January 20, 2029? Perhaps not. He isn’t much of a party man, after all. But his lack of consistent policy views almost guarantees that the party will descend into instant splintering once he steps away and that there will be no concrete movement with set principles that lives on, since he never tried to define them while in power.

This opens the door to the possibility that the party will seriously revamp itself post-Trump, continuing to pay homage to him as a person, without doing much to carry his approach, which automatically limits how much impact he will have post-2029. A president who governs from his “own mind” won’t have much of a philosophy to bequeath.

Gabe… IMO this is your most thoughtful and well-articulated column ever. You’ve captured the essence of government based on the showmanship and rantings of a sociopathic madman.

The two sole constants of the post-1968 Republican Party are what they have been since 1968: cutting taxes on rich people and using racism to get white people to buy into doing this by telling them that cutting taxes hurts black and brown people

Trump is not an anomaly: he is the epitome of the post-1968 Republican Party. He is what you get when Ronald Reagan kicks off his campaign in Philadelphia, Mississippi. The only reason the Republicans might change is because their efforts to bring Latinos into their fold were wrecked by Stephen Miller