How Trump’s War on Powell Could Backfire

The risks of going up against the Fed chair.

Good morning! It’s Monday, January 12, 2026. I told you on Friday that I was headed to the Supreme Court that morning, just in case the justices released their opinion on President Trump’s tariffs. They didn’t. In fact, they even mocked those of us assembled for thinking that they might: “Seeing who’s here, it’s not the case you thought,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor said, as the other justices laughed.

The opinion they did release was for a much lower-profile case called Bowe v. United States, which deals with how many times a federal prisoner can challenge their conviction. In an interesting lineup, the court’s liberals joined Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh in allowing the challenge to go forward, with the rest of the court’s conservatives in dissent. (The case also has interesting implications for Supreme Court reform.) The wait on tariffs continues.

And now to today’s top story…

Last weekend, President Trump sent troops to Venezuela. This weekend, he went to war with a target much closer to home: the Federal Reserve.

Of course, Trump battling with the central bank and its chairman, Jerome Powell, is nothing new. In his first term, Trump said he was “not even a little bit happy” with Powell, who he appointed as chair in 2018, because Powell was keeping interest rates too high. Since returning to office last year, Trump has launched a full-fledged campaign pressuring the Fed to lower rates, attempting to fire Fed governor Lisa Cook and trashing Powell as “Mr. Too Late” (because, Trump says, he should have started cutting rates earlier).

Then, last night, the New York Times reported that the Justice Department had opened a criminal investigation into Powell’s congressional testimony about the Fed’s ongoing renovation project, which appeared to be a major escalation in Trump’s pressure campaign. But the real bombshell came minutes after the Times report, when Powell said as much in an explosive two-minute video statement.

The video may not seem that dramatic — it’s just Powell calmly speaking to the camera, without any frills attached — but it’s incredibly rare for a Fed chair to directly and publicly respond to a president in this manner. And Powell didn’t mince words in the statement (emphasis mine):

I have deep respect for the rule of law and for accountability in our democracy. No one, certainly not the chair of the Federal Reserve, is above the law. But this unprecedented action should be seen in the broader context of the administration’s threats and ongoing pressure.

This new threat is not about my testimony last June or about the renovation of the Federal Reserve buildings. It is not about Congress’s oversight role. The Fed, through testimony and other public disclosures, made every effort to keep Congress informed about the renovation project. Those are pretexts. The threat of criminal charges is a consequence of the Federal Reserve setting interest rates based on our best assessment of what will serve the public, rather than following the preferences of the president.

This is about whether the Fed will be able to continue to set interest rates based on evidence and economic conditions, or whether instead monetary policy will be directed by political pressure or intimidation.

I have served at the Federal Reserve under four administrations, Republicans and Democrats alike. In every case, I have carried out my duties without political fear or favor, focused solely on our mandate of price stability and maximum employment. Public service sometimes requires standing firm in the face of threats. I will continue to do the job the Senate confirmed me to do, with integrity and a commitment to serving the American people.

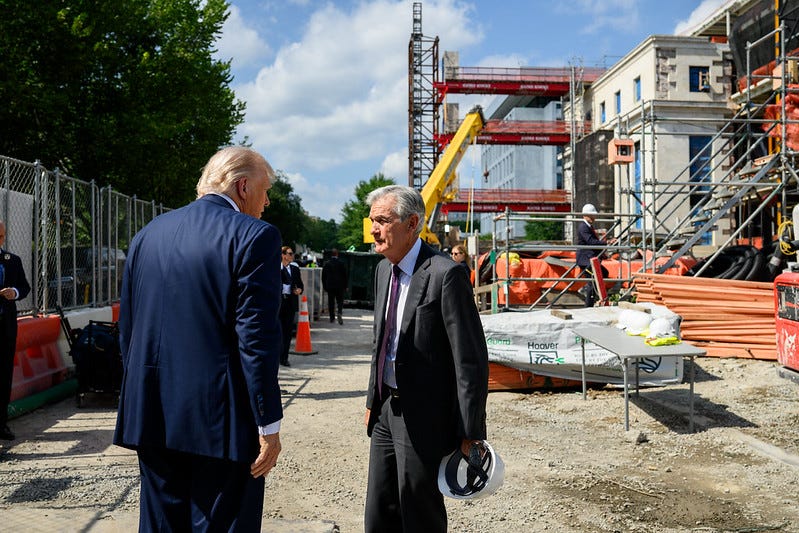

For years, as Trump has criticized him, Powell has stayed quiet in response. When Trump wanted to visit the Fed headquarters in July, which presidents rarely do, to see the controversial renovations himself, Powell acquiesced. In a scene that was already extraordinary enough, Powell (wearing a hard hat) did publicly contradict Trump during the tour, telling the president that he was miscalculating the cost of the construction. But he largely played the role of polite host, and has generally tried to dodge confrontation with Trump when asked about the president.

Now, though, with Powell’s statement directly accusing the administration of coming up with a pretext to criminally investigate him because they want the Fed to lower interest rates, not only is Trump going to war with the Fed — after months of trying to placate him, Powell is firing back.

As is so often the case, in trying to exert pressure on the Fed over interest rates, Trump is doing something previous presidents have done … but taking things many, many notches further.

In the 1950s, President Harry Truman wanted the Fed to keep interest rates on Treasury bonds low in order to continue financing the Korean War. The Fed wanted to increase interest rates to fight creeping inflation. Truman went so far as to summon the entire Federal Open Market Committee — the body that makes decisions about interest rates, composed of the Fed chair, the other six Fed governors, and four presidents of the regional Fed banks — to the White House for the first and only time. Truman quickly announced that the committee had agreed to his policy; one Fed governor decided to leak the Fed’s internal account of the meeting, contradicting his account.

The episode ended with Fed chair William McCabe being “informed that his services were no longer satisfactory,” as Truman put it. McCabe agreed to resign under pressure, but not before hammering out the Treasury-Fed Accord, which cemented the modern precedent of Fed independence from the sitting administration.

But that precedent has been tested again and again. In the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson literally shoved McCabe’s successor, William McChesney Martin, against a wall, physically pushing him to lower interest rates during another war. “Boys are dying in Vietnam and Bill Martin doesn’t care!” Johnson said to him. (Martin stood his ground in the moment, but did eventually start cutting rates.)

In the 1970s, President Richard Nixon declined to reappoint Martin, elevated Arthur Burns in his place, and then went on to pressure Burns to lower interest rates in a series of phone calls and Oval Office meetings while he was up for re-election. (Burns complied with Nixon’s demands, a decision that economists believe helped seed the “Great Inflation” of the decade.) In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan’s chief of staff told Fed chair Paul Volcker that the president was “ordering” him not to raise rates while Reagan was seeking a second term. (Volcker later said he was “stunned” by the demand, but that he already wasn’t planning to raise rates.)

In other words: it is normal for presidents to want interest rates low, in order to juice the economy in the short term — even though that can risk higher inflation over time. But that is precisely why the central bank has traditionally been placed independent of the White House, to ensure that decisions over monetary policy are made with the long-term health of the economy in mind, not the political considerations of the moment. When that tradition has been flouted in the past, the result has sometimes (as in the 1970s) proved disastrous.

To push for rate cuts of his own, Trump has already sought to fire Fed governor Lisa Cook. He formally claimed that he did so because Cook had allegedly committed mortgage fraud — but he explicitly tied the move to interest rates, telling reporters the day after the attempted firing that “people are paying too high an interest rate” but that “we’ll have a majority very shortly” (meaning that his ability to replace Cook would put him closer to having his appointees form a majority on the Fed board).

The Supreme Court, so far, has expressed a desire to keep the Fed isolated from political control, even as it moves to puncture the independence of other agencies: the justices thwarted Trump by opting to keep Cook in place, at least on a temporary basis. The court will hear oral arguments next week, on January 21, over how to rule in the Cook case permanently.

Trump now seems to be gunning for Powell as well while he waits for that decision.

We should quickly say a word about what, exactly, Powell is being investigated over.

Powell, the other Fed governors, and about 3,000 employees work out of two adjacent buildings in Washington, D.C. Back in 2018, the Fed acquired another building next door, with plans to renovate it to house additional offices while also renovating one of the existing Fed buildings. Since returning to office last year, among his many critiques of Powell, Trump has needled the Fed chair for the ballooning price tag of the construction project, which has grown in cost from $1.9 billion (its initial estimate) to $2.5 billion today.

The renovation controversy was the reason for the hard-hat tour that Powell gave Trump back in July.

According to Powell’s statement, the Federal Reserve was served by the Justice Department with grand jury subpoenas on Friday concerning testimony Powell gave about the renovation in June to the Senate Banking Committee.

We don’t definitively know which specific statements of Powell’s are under examination, but Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-FL), a Trump ally, previously submitted a criminal referral to the Justice Department about Powell’s testimony — and took credit on Sunday for the DOJ’s investigation — so that seems like a good place to start.

In her referral, Luna accuses Powell of making two “materially false claims” during his Senate testimony, in violation of 18 U.S. Code § 1001, which makes it illegal to make a false statement while testifying before Congress.

Here was the first claim that Luna labeled false, in which Powell is pushing back against reports about the renovation project:

There’s no VPI dining room.1 There’s no new marble. We took down the old marble, we’re putting it back up. We’ll have to use new marble where some of the old marble broke, but there’s no new. There are no special elevators. There’s just, they’re old elevators that have been there. There are no new water features. There’s no beehives, and there’s no roof terrace gardens.

The issue is, as Luna notes, all of these features (minus the beehives) are in the description of the renovation project that the Fed gave the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) back in 2021. But the Fed says there is a perfectly innocent explanation to the differences in Powell’s testimony and the NCPC submission. It’s not that one or the other is right, the Fed says. They both are. They argue that the submission accurately reflected the renovation plan as of 2021, but since then, the plans changed, and Powell’s testimony accurately reflected the renovation plans as of 2025.

There is no record of any such changes on the NCPC’s website — even though projects under its jurisdiction are supposed to alert the agency to any “substantial changes” to their plans — but the Fed argues a) that the changes weren’t substantial, and b) that the Fed isn’t subject to NCPC jurisdiction in the first place, and only submitted its plans in 2021 as a voluntary courtesy.2

The second alleged false claim is this:

When I was the administrative governor [of the Fed] before I became chair, I came to understand how badly the [Fed] building really needed a serious renovation, had never had one.

Luna says that this is false, because the Fed renovated its building between 1999 and 2003, “which included the replacement of the roof, all major systems, and a full refurbishing of interior and courtyard spaces.”

If it’s true that these allegations form the basis of the Powell investigation, it seems to me that there are at least three ways it could backfire for Trump3:

1. So far this year, Trump’s attempts to weaponize the Justice Department — another institution traditionally given independence from presidential control — have largely been foiled by the legal system. Grand juries have repeatedly refused to bring indictments sought by the DOJ; in other cases, the indictments have been dismissed by a judge.

To the extent the Justice Department is actually planning to bring charges against Powell — and not merely using the threat of charges as a way to pressure him — an indictment along the lines of Luna’s referral could very likely suffer the same setbacks as Trump’s other ill-fated revenge prosecutions.

From my perspective, the second alleged false claim is purely subjective, hinging on what one considers to be a “serious” renovation. (This is somewhat similar to the James Comey indictment, which also hinged on vague testimony before Congress.) The story behind the first alleged false claim seems to be that the Fed renovation really was going to include some unnecessary extravagances, but that they no longer plan to include them. Would they have made those changes without the scrutiny from Trump? Perhaps not, so maybe it’s a good thing that Trump brought public attention to the renovation. But that doesn’t mean Powell committed a crime. As long as the Fed can prove that the changes were made before his Senate testimony, and that he was accurately reflecting the Fed’s plans at the time, he is probably in the clear legally. Just because those extravagances were part of the plan c. 2021, it doesn’t mean that Powell was lying in 2025, though he could have been more forthright about them being dropped.

If the DOJ does try to move forward here, it will probably face the same embarrassment it has faced when trying to prosecute other perceived Trump rivals.

2. That said, few people believe that this is really about the Fed renovations. Even if the false statements case against Powell was rock-solid, it would still be extraordinary for the Justice Department to investigate a sitting Fed chair for something as pedestrian as plans about water features and whether a roof replacement constitutes a “ serious renovation.” Powell said openly what basically everyone in Washington already believed: that such an obscure investigation was clearly a pretext for exerting pressure on the Fed chair, and trying to place yet another historically apolitical institution under his control.4

This could backfire because there are many congressional Republicans who very much like Powell (an establishment Republican figure who was confirmed with 80+ votes in the Senate), admire his handling of the economy (particularly during Covid), and do not want to see Fed independence tampered with.

Powell is already on his way out as Fed chair: his term expires in May. Trump is reportedly leaning towards nominating White House economic aide Kevin Hassett for the post, although he is also considering Fed governor Christopher Waller, former Fed governor Kevin Warsh, and BlackRock executive Rick Rieder.

This investigation into Powell will not help Trump confirm his chosen replacement for Powell, whoever that ends up being. Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC), who is retiring but remains in office until January 2027, blasted the DOJ for opening its investigation last night and announced that he will “oppose the confirmation of any nominee for the Fed—including the upcoming Fed Chair vacancy—until this legal matter is fully resolved.”

Tillis matters because he sits on the Senate Banking Committee, which is split 13-11. Without support from Tillis or any Senate Democrats, no Trump nominee will be able to receive approval from the panel. Without approval from committee, no nominee can receive a vote on the Senate floor.5

Tillis is making Trump choose: he can either drop this investigation into Powell, or kiss his chances of a handpicked Fed chair goodbye. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) also labeled the Powell investigation an “attempt at coercion,” making clear that the legal spectacle will only complicate Trump’s hopes of confirming a Fed chair down the line.6

3. The pressure campaign might lead to Powell simply digging in his heels. The Federal Open Market Committee will convene for its next meeting on January 27. With inflation remaining above the Fed’s target, and the labor market not appearing in need of urgent rescue, analysts already thought that the Fed was likely not to cut interest rates again after its next meeting, despite Trump’s urging. Now, Powell might be even less likely to heed the president’s demands.

The legal threat could also persuade Powell to remain on the Fed board after his term as chair expires. Although Powell’s term as chair expires on May 15, his term as a Fed governor lasts until January 2028. Fed chairs typically leave the board when their term as chair is up, even if they have more time on their term as a governor, but Powell could opt to stay.

This creates two issues for Trump. First of all, the president can only nominate a Fed chair from the existing group of Fed governors. If Powell steps down as governor and chair (as is traditional), Trump can simply pick someone to replace Powell as governor and make that person chair as well.

But if Powell decides to stay on as a governor, Trump has two choices: he will either have to elevate finalist Christopher Waller, a sitting Fed governor, as chair or he will have to take his ally Stephen Miran (whose term as governor expires on January 31) off the board and use that seat to nominate the person he wants to serve as chair.

The second issue Powell could create is that if he stays on as a governor, he could continue to vote against rate cuts, haunting Trump even as a former chair. If Powell stays on the board, Trump can likely count on Waller and Miran (or Miran’s replacement, if Trump uses that seat to name a chair) to vote for rate cuts — but that’s only two votes out of 12 on the Federal Open Market Committee. A Powell vacancy also wouldn’t guarantee that other members of the panel would suddenly vote Trump’s way, but it would at least give Trump a third vote who likely would follow his wishes. Powell remaining as a governor makes it that much harder for Trump to coalesce a majority behind rate cuts, which will already be tricky regardless.

If Powell is looking for inspiration to dig his heels in, he won’t have to look far. One of the Fed’s two existing buildings — the one that’s causing all the furor about renovation costs — is called the Marriner S. Eccles Building, and it’s named for the last Fed chair who stayed on as a governor after ending his term as chair.

Eccles was appointed Fed chair by FDR in 1934; when his term was up in 1948, Harry Truman declined to reappoint him. Eccles got his revenge by staying on the Fed board; when Truman later summoned the Federal Open Market Committee to the White House and released a slanted version of the meeting, Eccles is the governor who leaked the Fed’s contradictory account.

And the Fed’s other building? It’s named for William McChesney Martin, who Truman installed as Fed chair after that Korean War-era confrontation. Martin would later come to literal blows with LBJ, as recounted above, but — like Powell — he also clashed with the president who appointed him.

Martin was an official in the Truman Treasury Department, but once he became Fed chair, he decided not to follow Truman’s wishes and instead worked to establish the norms of Fed independence that (largely) live on to this day. Many years later, when both men were out of office, Truman and Martin ran into each other on the streets of New York City.

Truman stared straight at him, said one word — “Traitor” — and then walked on.

Powell presumably meant to say “VIP.”

The NCPC, by the way, is the same agency which is currently reviewing Trump’s White House ballroom project, making it an unexpectedly relevant player in two ongoing controversies — and making it somewhat ironic that Trump is going after someone for an expensive renovation at the same time as he is executing one himself, although it should be noted that the Fed renovation is being paid for by official funds and the White House renovation is not.

And remember: this is only the ways that going after Powell could backfire for Trump personally. Many economists agree that chipping away at Fed independence comes with a whole other set of risks for the long-term health of the economy more broadly

Trump, for whatever it’s worth, told NBC News last night that he had no involvement in the Justice Department probe of Powell. In addition to previously musing about firing Powell, though, Trump said just last month that “we’re thinking about bringing a suit against Powell” in relation to the renovations.

The investigation is being overseen by close Trump ally Jeanine Pirro, the former Fox News host turned U.S. attorney in Washington, D.C.

There is a way to force a nomination straight to the Senate floor without committee approval, but it requires 60 votes, which Trump is certainly not going to get here.

Under 12 U.S. Code § 244, if a new Fed chair is not confirmed by the time Powell’s term ends on May 15, the Fed board can elect a governor to serve as chair pro tempore. The last three times this happened, the sitting chair has been elected chair pro tempore, which means these legal threats could actually lead to Powell’s time as chair being lengthened, if it leads to GOP hesitations, which lead to no chair being approved by May, which lead to Powell being elected chair pro tempore.

What a great analysis! I had no idea what Powell’s options were, I just assumed he had to leave when his term ended. I sure hope he stays to haunt Trump. Also, had no idea my Representative Luna had her hands in this, but I’m not surprised.

Fascinating background and analysis. Thanks for writing this. I note that there's not much stock market reaction today (12 January) to all this--I wonder if they have come to the same conclusions as you have. It also seems stunningly necessary, since the chair's term ends this spring. But maybe the president is hoping the criminal investigation will take him off the board so that he cannot remain after his term as chair expires. I agree with you that I think that will fail.

I should mention those of us who bought our first house in 1981, when the prime was around 21%, have a very keen interest in what happens with the Fed. Our current house, which we bought in 2001 at 6%, seemed a bargain in comparison. It's been paid off for years, fortunately. The very low interest rates of recent years seem much more of an anomaly to us.