Where Trump does — and doesn’t — have a mandate

Analyzing the national mood swing.

Good morning! It’s Thursday, January 23, 2025. The 2026 midterms are 649 days away.

I’m Gabe Fleisher, and this is Wake Up To Politics, your daily guide to the latest news from Washington. Let me know how I’m doing: get in touch at gabe@wakeuptopolitics.com.

If there’s one thing that liberal and conservative pundits agree on right now, it’s that the conservatives are winning.

I don’t just mean that Republicans are succeeding in pushing public policy to the right. That much is obvious: we’ve all seen it with our own eyes since Monday. The more interesting contention being made is that conservatives have succeeded in pushing public opinion in their direction as well — or, at least, it feels like they have.

“There’s been a significant ‘vibe shift’ in American politics,” Jonah Goldberg argues from the right. “The election was close,” Ezra Klein agrees from the left, “but the vibes have been a rout.”

This has been several months (really, years) in the making: back in October, Semafor reported that “no matter who wins,” public opinion in the U.S. “is moving to the right,” citing a sharp turn on immigration, among other issues. Then Donald Trump waltzed back into the White House, and suddenly the “vibe shift” was hard to ignore.

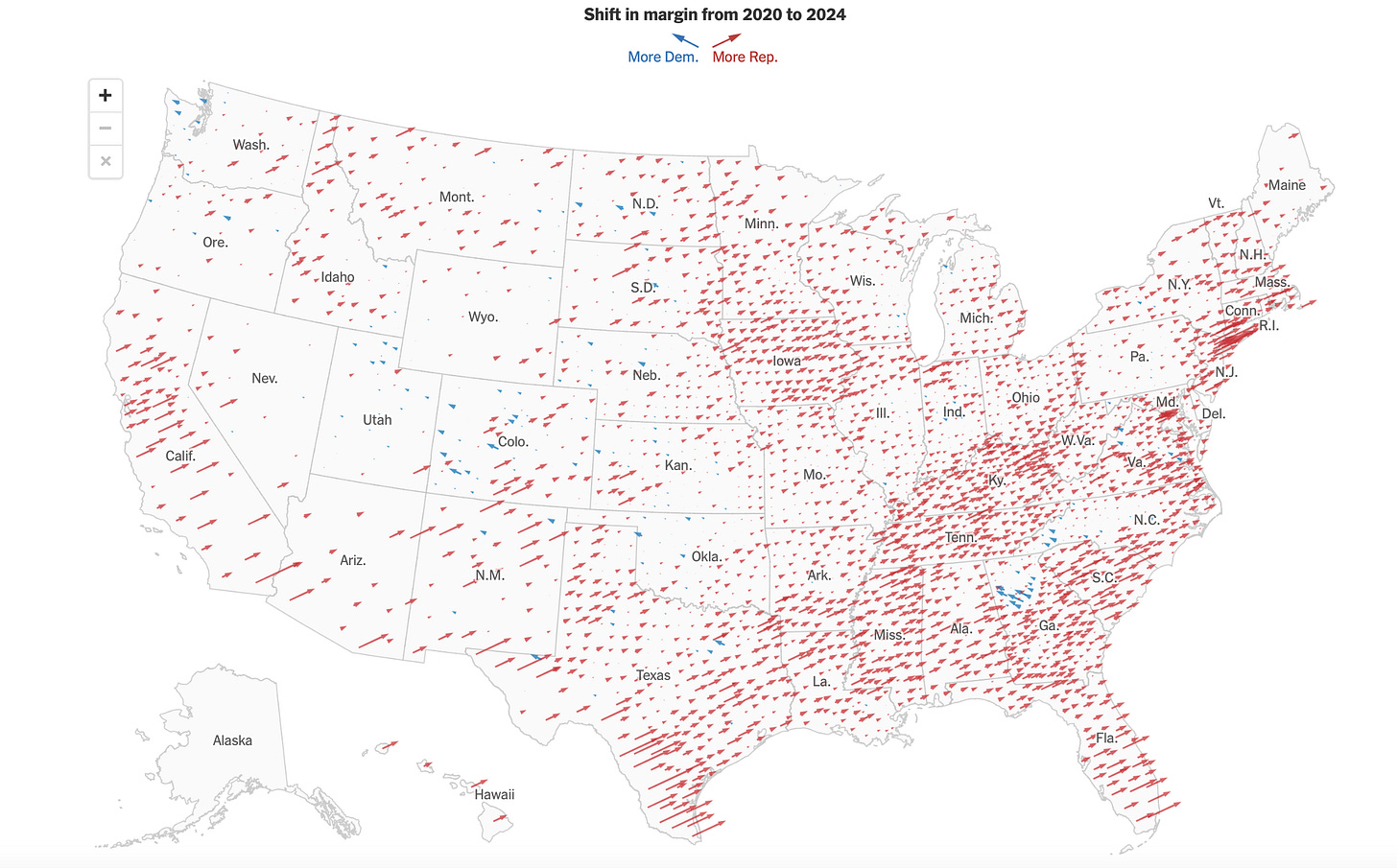

After all, Trump didn’t just win the presidency: he also won the popular vote, which had eluded him in two previous elections. And not only that: he also managed to swing almost every county in the U.S. in his direction. And not only that: he also picked up significant ground among key demographics (Hispanics, young voters) that Democrats have traditionally regarded as loyal supporters.

And not only that, but he is now more popular than he’s ever been — including among a powerful and visible coterie of business leaders, tech titans, and cultural figures who have gone from being anti-Trump in 2017 to Trump-curious (or more) in 2025.

But, at the same time, the election was close. Trump said on Inauguration Day that he “won in record fashion.” He didn’t, unless you count the 44th-largest Electoral College margin and 49th-largest popular vote margin (out of 60 elections) as record-breaking. He did sweep the swing states, but he also won the popular vote by only 1.5 percentage points, coming just short — 49.9%! — of a majority. By the same token, his party secured majorities in both chambers of Congress, but several Republican Senate candidates badly underperformed Trump and were defeated in key states. The party’s House majority is historically fragile.

So, which is it? Epochal vibe shift or familiar nail biter?

Well, I always like to tell you how things are, not how they feel like. And — no disrespect to my distinguished pundit colleagues — some of these analyses seem a little high on conjecture and light on data for my comfort.

In general, one of my great frustrations in politics is that it feels like so many people (from professional talking heads to casual conversation partners) make broad, confident statements about public opinion (usually about how their stance on an issue is widely shared) without even trying to check to see if the claim is true.

I suspect this is a problem that pre-dates social media, but it seems like it has gotten worse in an age of heightened information silos. Sure, everyone you know or get your news from might support a particular position, but that does not mean a majority of the country takes that stance as well. (Call this the Pauline Kael Problem.)

Just as it’s important for politicians to be in touch with the opinions of their constituents — “Public sentiment is everything: with it nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed,” Abraham Lincoln once said — it’s incumbent on “civilians” observing and commenting on politics to have a rough understanding of where the public stands on issues as well.

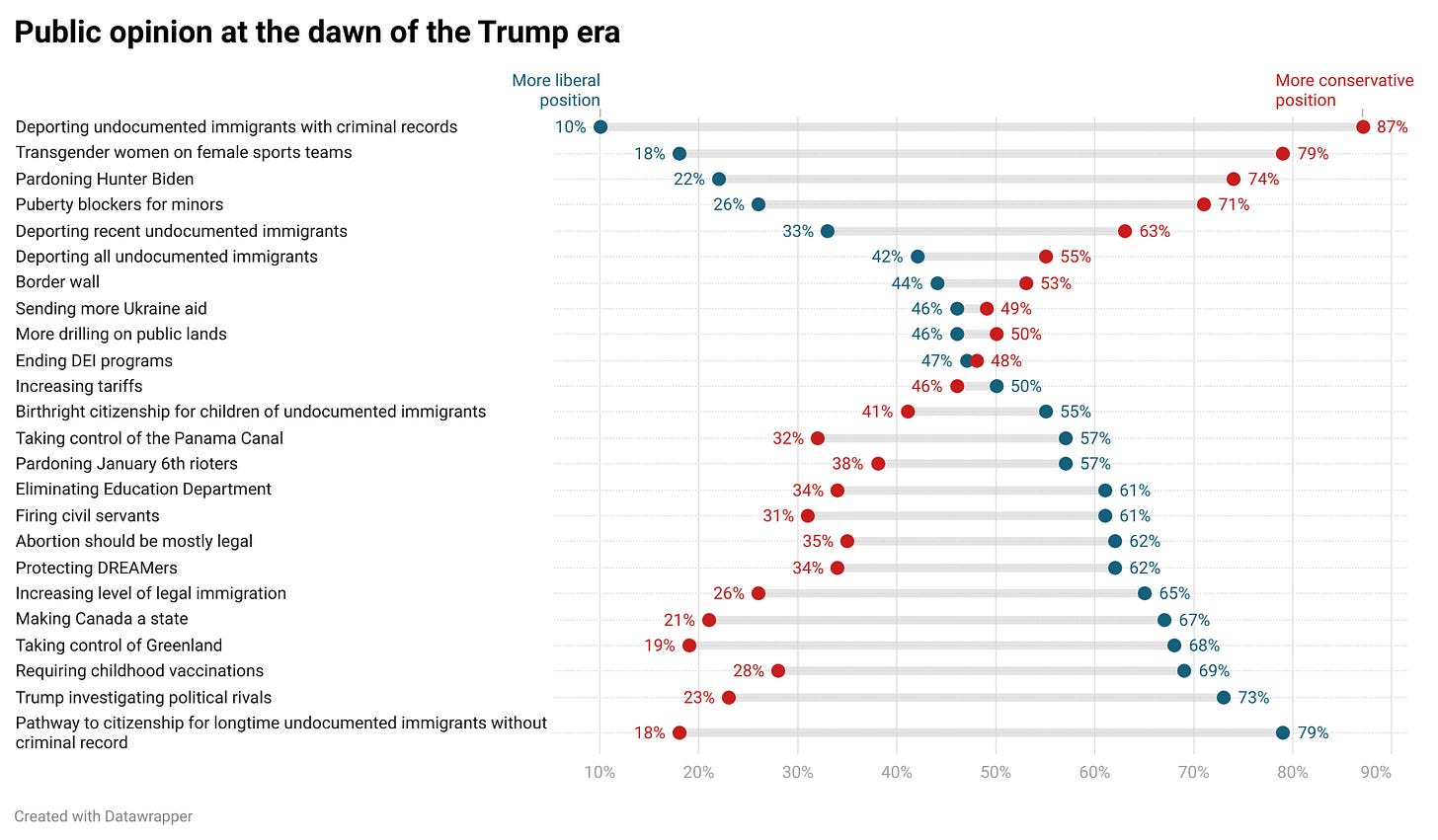

So, let’s start our analysis of the second Trump era firmly grounded in the data, to acquaint ourselves with the field of play we’re talking about. In the below graph, I’ve taken a slew of questions from recent polls by the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. The red dots shows the percentage support for the more conservative position on each question. The blue dots show the liberal position.1

We’ll return to this graph later on. The point for right now is to take a second and familiarize yourself with it — inoculate yourself with the data, like antibodies to ward off innumerate arguments. Take a look at where the public agrees with you, and where it doesn’t, and adjust your priors accordingly. We can’t have an analytically sound conversation without doing so.

Just glancing at the data, my first-pass take here is that Trump is clearly benefitting from a new wave of public support on several important issues, but the supposed, broad-based shift towards conservative opinion doesn’t seem as pronounced as some commentators are making it out to be.

Then again, I’m no expert. So I called up someone who is.

You might not know the name Jim Stimson, but he’s the kind of person who makes academics at political science conferences fall all over each other. A legendary professor at the University of North Carolina, he’s best known for his annual reports on the national mood.

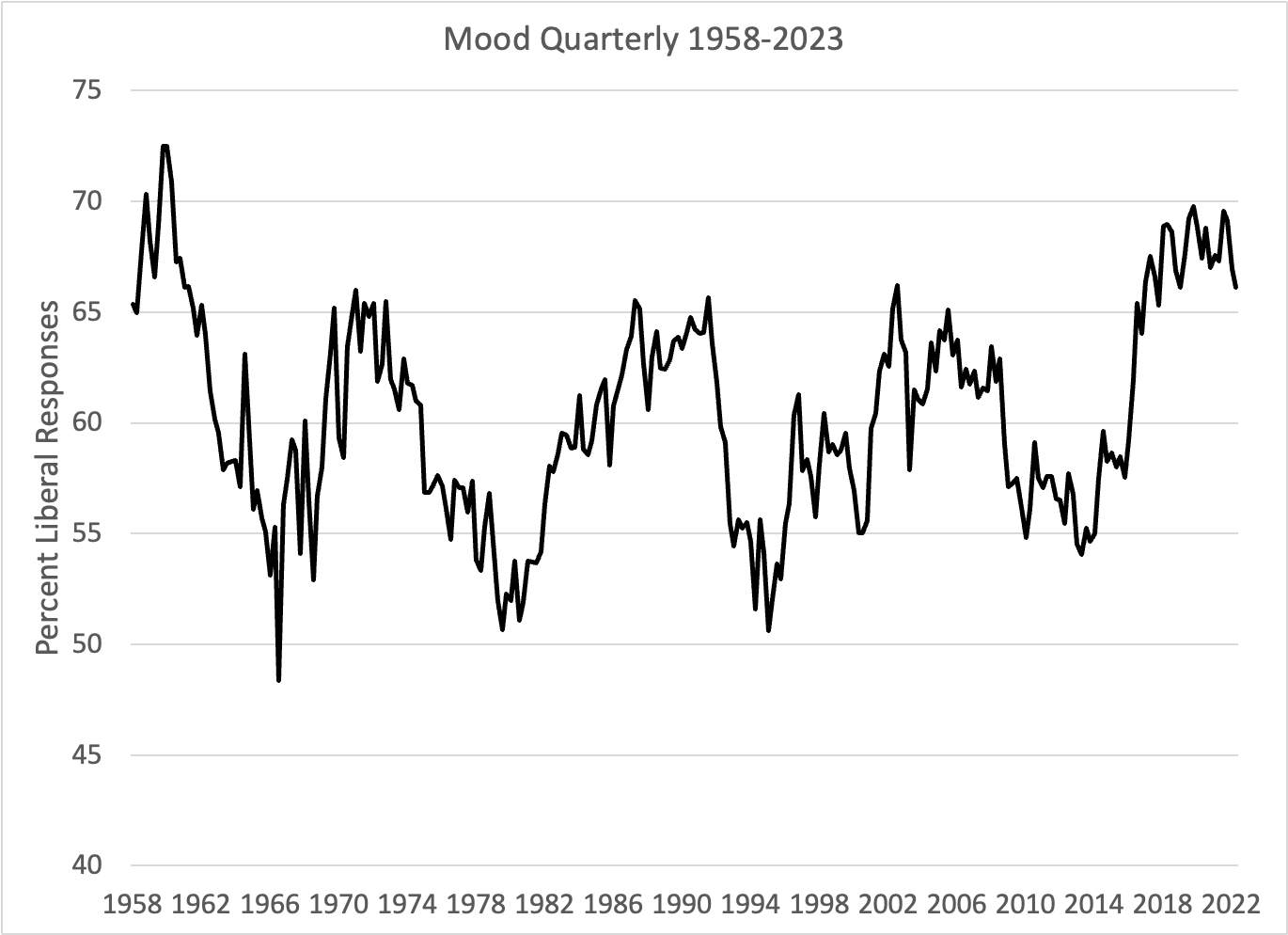

Assessing the country’s mood might not seem any more quantitively rigorous than taking stock of “vibes” — a practice I just dismissed in the previous paragraphs — but, in this case, it is. In 1991, Stimson created an index that takes dozens of different polling questions and aggregates them into a measure of what he calls the “Public Policy Mood” of the country. He’s been updating it ever since.

Stimson, in other words, has been studying national vibe shifts since long before “vibe shifts” entered the political lexicon (and by marshaling actual data, not just speculation). Here’s a look at his findings, of how the ideology of America’s “Public Policy Mood” has evolved over time:

As of now, Stimson’s index only goes up to 2023 — he plans to update it after new data becomes available this spring — but there’s probably no one more qualified to give a gut-level assessment of whether the U.S. is experiencing a national mood swing to the right.

He said in a phone interview on Wednesday that we probably are. “I think if I were to do it these days, I’d see a fairly strong movement toward conservatism,” Stimson told me.

If that’s true, why doesn’t it show up more clearly in my chart of polling data? That’s because I’m using the wrong data points, says Stimson. It’s true that Trump isn’t aligned with the electorate on several of-the-moment issues — like whether the U.S. should take over Greenland — but the mood index is designed to filter out exactly those types of ephemeral questions. Instead, Stimson focuses on longer-running debates which, he says, are more predictive of voter behavior and attitudes.

Opinions on size of the government are most influential to his model. Here’s a rough proxy of how this works, using a single metric: the Pew Research Center’s question of whether the government should be big or small. This is way less sophisticated than Stimson’s method, but I just want to show you the type of trends he’s tracking:

2014: 53% said smaller government, 38% said bigger government —> Policy Mood was turning more conservative

2020: 52% said bigger government, 45% said smaller government —> Policy Mood was turning more liberal

2024: 51% said smaller government, 46% said bigger government —> Policy Mood is likely turning more conservative

These are the sorts of questions that makes Stimson think that the country’s mood ring is, in fact, turning red.

But that doesn’t mean pundits announcing a huge swerve will be right for long. It may feel like the current vibe shift is different (and more durable) than previous ones — but “it always does in the months immediately after an election,” Stimson reminded me.2 “And then it fades.”

Stimson’s data has been influential in shaping one of the most prominent findings in political science: that the American electorate behaves basically like a thermostat. Push policy in a conservative direction, and public opinion will self-regulate in a liberal direction. Make policy more liberal, and the country will grow more conservative.

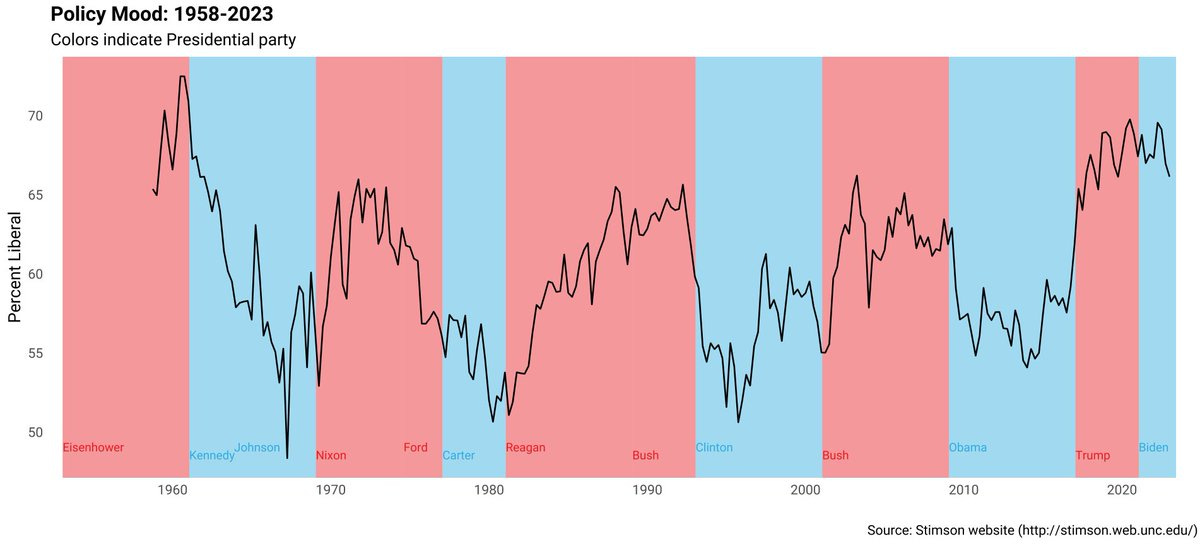

For proof, take a look at Stimson’s graph again, except this time overlaid with which party controlled the presidency:

The trend is undeniable: when Democrats control the White House, the country’s mood turns more conservative. Once a Republican is sworn in, it isn’t long before opinions shift to the left. This is the reason why the first midterm election after a president’s term begin almost always goes in the out-party’s direction.

This trend will continue, Stimson confidently told me; the current vibe shift will be short-lived. (He also said to discount the seeming durability of liberalism at the beginning of the Biden era. Once the full sweep of his presidency is calculated, Stimson expects it to show a sharp drop.)

Full disclosure: I knew Stimson would say this to me; in fact, I called him so he would share exactly that perspective. (It’s not like he’s made a secret of his theory: “A great number of trees are felled to make all the paper on which pundits assert that true opinion change in America is toward liberalism or, with wholly equal falsity, toward conservatism,” Stimson wrote in 2023, before the most recent such assertions. “The behavior of mood suggests the true answer. Opinion does not trend in either direction; it cycles contrary to party control of government.”)

But I still didn’t want to let him off the hook that easy. Playing devil’s advocate, I tried lobbing out a few theories for why maybe the theory of thermostatic public opinion — and Stimson’s broader model, developed during the George H.W. Bush presidency — won’t hold up as well in the modern era, why maybe the current vibe shift could be here to stay:

Stimson’s model preferences issues like size-of-government, which often aren’t as salient in our current political conversations as social issues (immigration, abortion, etc.)

Also, size-of-government (among other issues) isn’t as easy to map onto partisan lines any more: it’s not like Republican president Donald Trump is exactly a champion of smaller government.

The media climate is changing, such that it might be more common for voters (depending on how they get their news) to not know about a major policy shift, which could make it harder for them to be upset by it. (In general, it seems like one lesson of the Biden era is the connection between policy shifts in Washington and voter behavior across the country is beginning to fray.) Perhaps, in today’s world, how you come across on social media is more relevant than how you’re changing policies.

Stimson, 81, listened respectfully, but he wasn’t impressed with any of these theories. “The size-of-government issues have a smaller proportion of the headline news than they used to,” he acknowledged. “But in the underground shaping of attitudes, the consistency is overwhelming.”

It’s also true that media consumption is changing — but his research finds that no matter which policies a president enacts, voters will infer that the policies are moving in a conservative direction if it’s a Republican and vice versa if it’s a Democrat, and their moderate sensibilities will be offended accordingly.

Our country may be moody, he said, but predictably so. “We know how [public opinion] moves,” Stimson told me. “It moves cyclically, in contrast to whoever is in power at the moment.”

Eventually, I proposed a compromise. Stimson, you see, is also an expert on another topic that’s been in the news lately: electoral mandates. (He literally wrote the book on them.)

In their 2006 book, Stimson and his co-authors write that a political party only has a mandate when three groups — the winning party, the losing party, and the media — agree after an election that voters were trying to send a clear, overwhelming message with the result. They argued that only three such mandates have been notched in modern history: by Lyndon Johnson in 1964, by Ronald Reagan in 1980, and by congressional Republicans in 1994.

His ruling on 2024? “No mandate,” he told me. “A normal election.”

But let’s return to my graph of public opinion:

One thing that jumps out pretty clearly here is that Trump does command broad public support in two important categories: immigration and transgender rights.

87% of Americans want to increase deportations of undocumented immigrants with criminal records. 79% don’t want transgender women playing on female sports teams. Those are big, message-sending numbers.

And, I would argue, the media and both parties are treating the election results as having sent a clear message on these two issues. (It’s no accident that one of Trump’s most effective campaign ads combined both of them.) Certainly, on immigration, Democrats seem to be changing their tune after the election: look at the bipartisan vote on the Laken Riley Act. To a lesser degree, some Democrats are talking about new messaging on transgender rights, too.

Perhaps Trump does have a mandate, but just on these two issues, where it’s clear that public opinion has swung sharply to the right.

“Trump does have support on the key issue of immigration,” Stimson allowed. “But what we know is that people’s issue attitudes are not highly correlated. So the fact that that there’s movement on immigration doesn’t mean that there’s movement on the basic issue domain [which he views as primarily fiscal]. And so, for example, if Trump does another tax cut, which we all expect, which will benefit the wealthy at the expense of the poor, it will be highly unpopular.”

Even if Trump does have a mandate on immigration, Stimson added, he is likely to misuse it.

“If you talk to individual members of the public, they say ‘yes’ on mass deportation,” Stimson said. “What about splitting up families? ‘Oh, hell no.’ They don’t want to do that. They haven’t thought through the consequences of what mass deportation means.”

“What about causing inflation in the American economy, because we’re talking about deporting three or four percent of the workforce? They don’t want that. So they want the rhetoric, but not the actual policies as they come to ground, as we experienced with Trump in the first term. Family separation was what undermined his whole immigration push. The public didn’t like it, and they aren’t going to like it any better now.”

This shows up in the Times and Journal polls. The public supports Trump’s immigration policies, but only to a point: 52% support mass deportations, according to the Journal poll — but that goes down to 46% if you mention that “businesses will face worker shortages.”

In the Times poll, 74% support deporting undocumented immigrants with criminal records — but that goes down to 38% when you mention separating families, and down to 26% when you ask about undocumented immigrants who have been here for 10 years and have no criminal record.

As popular as deporting undocumented immigrants with criminal records is, so is giving a pathway to citizenship to those without a criminal record. Birthright citizenship is also popular; so is raising the level of legal immigration.

This introduces a strikingly different way of looking at the election results. If you accept Stimson’s thinking, it would mean the results were more a result of dissatisfaction with inflation and the economy — mixed with nuanced, conditional support for some of Trump’s proposals — than a broad-based lurch to the right.

It would mean that Democrats don’t need to to search for new immigration messaging, as many members of the party are urging. “All the Democrats need to do is is wait for the calendar,” Stimson told me.

And it would mean that Trump would be smart to talk tough on immigration — to reassure a public that is clearly anxious about the issue — but not to actually push much beyond the record level of deportations under Biden. He should communicate as though he is doing more, but if Americans start seeing the effects of actual heightened deportations, he might lose their support.

Stimson compared it to the Dobbs decision: “Talking about abortion was always good politics [for Republicans]. Actually outlawing it was terrible politics.”

On transgender rights, as well, most polls show Americans uncomfortable with allow transgender women to use female restrooms or play on female sports teams — but they also support a baseline level of protecting transgender people from discrimination. If Trump veers too far in demonizing people, not just riding the backlash to allowing transgender women in female public spaces, he risks engendering an entirely new backlash of his own.

On both counts, Trump may have mandates — but they’re narrow, to take certain, specific actions and nothing more. Trump, being Trump, is unlikely to make the milder (but politically safer) play — which is why Stimson is confident thermostatic public opinion will ultimately win the day. “Presidents overreach with great predictability,” he told me. “They make commitments to their primary electorates, which push them to go too far to either side for the electorate, and then the moderate electorate pulls them back.”

I think this model is broadly true — although I also think it also overlooks some risks for Democrats (and advantages for Trump). The Democratic brand, partially because of issues like immigration and transgender rights, is pretty tarnished in a lot of states: that doesn’t mean they can’t recapture the presidency, but it might mean changes are required to win a comfortable Senate majority any time in the near future. Movement among young voters, and changes in the media environment, also offer warning signs.

These possibilities aside, Stimson expressed confidence that history would repeat itself, just like it always has. “If you hold a discussion among journalists about whether the recent election was a typical election or something heralding something new and special, ‘new and special’ wins every time,” Stimson said.

Guilty as charged, I guess.

“Hold that same conversation among political scientists,” he continued, and ‘same old thing’ wins every time. I am a political scientist, so I’m gonna say, [journalists have] said after every election, ‘this one was different than all the others,’ but in the long haul, and judged dispassionately, they aren’t.”

Obviously, this doesn’t mean every Republican holds the “more conservative position” or every Democrat holds the “more liberal position.” But they’re coded for the response that is closer or farther to the message each party generally preaches. Issues that are hard to code on partisan lines (like Israel aid, or taxing Social Security benefits) were not included.

As if to prove his point, take a look at how past editions of Stimson’s policy mood index have been covered in the media: “Americans are more conservative than they have been in decades” (2013, Washington Post); “The US is in a VERY liberal mood right about now” (2019, CNN). The shifts receive breathless coverage, but then they never last.

This looks like detailed work. I applaud the effort and time it took you Gabe.

I tried three times to read it and had to stop. It’s me, not your work. I can’t pinpoint if it’s because I had a migraine last night and my brain cells are still recovering or that statistics makes my brain glaze over or that I cannot, simply cannot, absorb any data right now that says the majority of the country I served is veering into hateful, tight-ass land.

Yes, immigration needs a complete do-over. We need multiple check-in points along our borders and next to major airports - nice buildings built strictly for this purpose. Enough personnel - admin, legal & medical - to run the check-ins. Clean, safe, nice dorms to house everyone coming in while their paperwork and background are checked. Good food, medical checks, interpreters…it’s not that difficult to set up nice facilities with clear cut rules. Some say “don’t come here!” (Harris) as if that’s the solution. Others take a ‘I hate everybody’ approach (miller, holman & trump). Where are the common sense policies? The humane policies? Unless you are 100% native born you are here because you or your ancestors immigrated here. Immigration is a legal right here. Let’s do it properly, ethically and humanely.

People need to quit acting like it’s their job or religious quest to tell other people how to live. Humans come in an amazing range of variety - cisgender, bisexual, nonbinary, transgender and so on. What business is it of one person to dictate to another who they are? I had to grow up in a religious cult that harangued and shamed other people to live by their rigid definitions of what kind of a person was acceptable. Thiy did this to people they didn’t know and didn’t even interact with. I’m sick & tired of this. Think of all the energy humans would have to solve hunger, poverty, justice inequality, economic inequality, cure diseases …if they’d just stop bothering others for who they are.

We all need to start focusing on improving our own lives and communities in order to improve society as a whole and not by excluding others for who they are or where they’re from.

Thank you for this post. I appreciate getting factual information from professional sources. Historical data provides a more balanced perspective.

Your posts are the only ones I’m reading right now bc everything else is filled with too much drama.