Trump Has Forgotten Why He Won

A cautionary tale of presidents growing distracted.

In the fall of 2011, then-President Barack Obama’s closest advisers gathered in the White House to plot their strategy for his fast-approaching re-election campaign.

Obama announced to his aides that he had been up until 2 a.m. the night before, engaging in one of his favorite exercises: unloading his thoughts onto a yellow legal pad. He had put together a list of issues that he wanted to focus on in his 2012 campaign and then — if it was successful — in his second term.

“Most of his advisers had expected him to bring a list—but an index card, not War and Peace,” Mark Halperin and John Heilemann reported in their bestselling account of the 2012 election. Obama had filled up nine or ten pages of the legal pad “with his neat, compact southpaw handwriting,” as the duo put it.

Recalling the same meeting, Obama strategist David Axelrod reprinted an abridged version of the list in his 2016 memoir: “Immigration reform, climate change, Guantánamo, poverty, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and of course gay marriage, something that had vexed him for years.”

Obama’s aides listened to the list politely and then effectively told the president: Yeah, we aren’t going to talk about any of that.

As “weighty” as those issues were, Axelrod wrote, “none of them rose to the top of the list of concerns in a country where the economy was still weak and the middle class was under siege.”

Focusing on them “would detract from our ability to drive the winning economic argument,” he continued. “While some of these issues (gay marriage, immigration reform, climate change) had important, targeted appeal, we simply couldn’t afford to make them the focus of the campaign to the exclusion of our economic message.”

Obama heeded the advice and reoriented his campaign around a more economic-focused message, ditching the social issues he was more interested in pursuing to instead package himself as a populist and rival Mitt Romney as a plutocrat. The rest is history.

It’s the economic messaging, stupid

Obama was not the first — or last — president to stray from a core economic message to his peril. Perhaps most famously, Bill Clinton’s campaign team hung a sign in their Little Rock headquarters to remind themselves not to get distracted. “It’s the economy, stupid,” the sign read.

By now, that saying has become a cliché, but I think sometimes people misinterpret it to mean that a president can only be re-elected — or, in their second term, maintain popularity — if the economy is strong. That’s not true, and Obama 2012 is a great example: he won that campaign despite a sluggish economic recovery, with a higher unemployment rate than any re-elected president since the Great Depression.

But what the maxim does mean is that presidents are unlikely to remain politically successful if they don’t at least center the economy in their messaging, since it will always be the foremost issue on voters’ minds. It’s possible to win with a shaky economy, as Obama did, but it requires a relentless focus on communicating to people that you feel their pain, you will be able to fix it, and your rivals would do worse.

Which brings us to Donald Trump.

In some ways, the 2024 election is the inverse of 2012: economic indicators showed a much better performing (if imperfect) economy, but the incumbent party’s two candidates — Joe Biden and then Kamala Harris — were both unable to communicate effectively on the economy with voters. That left a vacuum for the challenger, Trump, who repeatedly promised in his ads and rallies to quickly improve the economy, especially by bringing down inflation.

Then, the message worked, and he immediately moved on from it.

When Clinton delivered his first address to Congress in February 1993, he began by acknowledging that presidents usually use the opportunity to “comment on the full range in challenges and opportunities that face the United States.” But, Clinton continued, “this is not an ordinary time, and for all the many tasks that require our attention, I believe tonight one calls on us to focus, to unite, and to act. And that is our economy.”

Similarly, in Obama’s first speech to lawmakers in 2009, he started out by saying, “I know that for many Americans watching right now, the state of our economy is a concern that rises above all others. And rightly so.”

At Trump’s address to Congress last week, he too declared that one of his “very highest priorities is to rescue our economy and get dramatic and immediate relief to working families.” But it took him 20 minutes to get there. Trump ticked through his national border emergency, the renaming of the Gulf of America, DEI policies, critical race theory, transgender women playing sports, and the Paris climate accords — all issue areas that would have fit on the 2011 list that Obama’s advisers dismissed as overly niche — before arriving at the economic section of his speech.

Trump then went on to devote significant time in the address to tariffs, even though 68% of Americans believe that import taxes will result in higher prices, according to a recent poll, in contradiction of his campaign promises.

Twice, Trump acknowledged that the tariffs might have temporary negative impacts, although he assured Americans that in the long term, they would deliver gains. Farmers will “probably have to bear with me,” he said. Later, he added of the broader economy: “It may be a little bit of an adjustment period. There will be a little disturbance, but we’re okay with that. It won’t be much.”

An unheeded warning

Trump is beginning to find out whether Americans are “okay” with a “little disturbance,” after all.

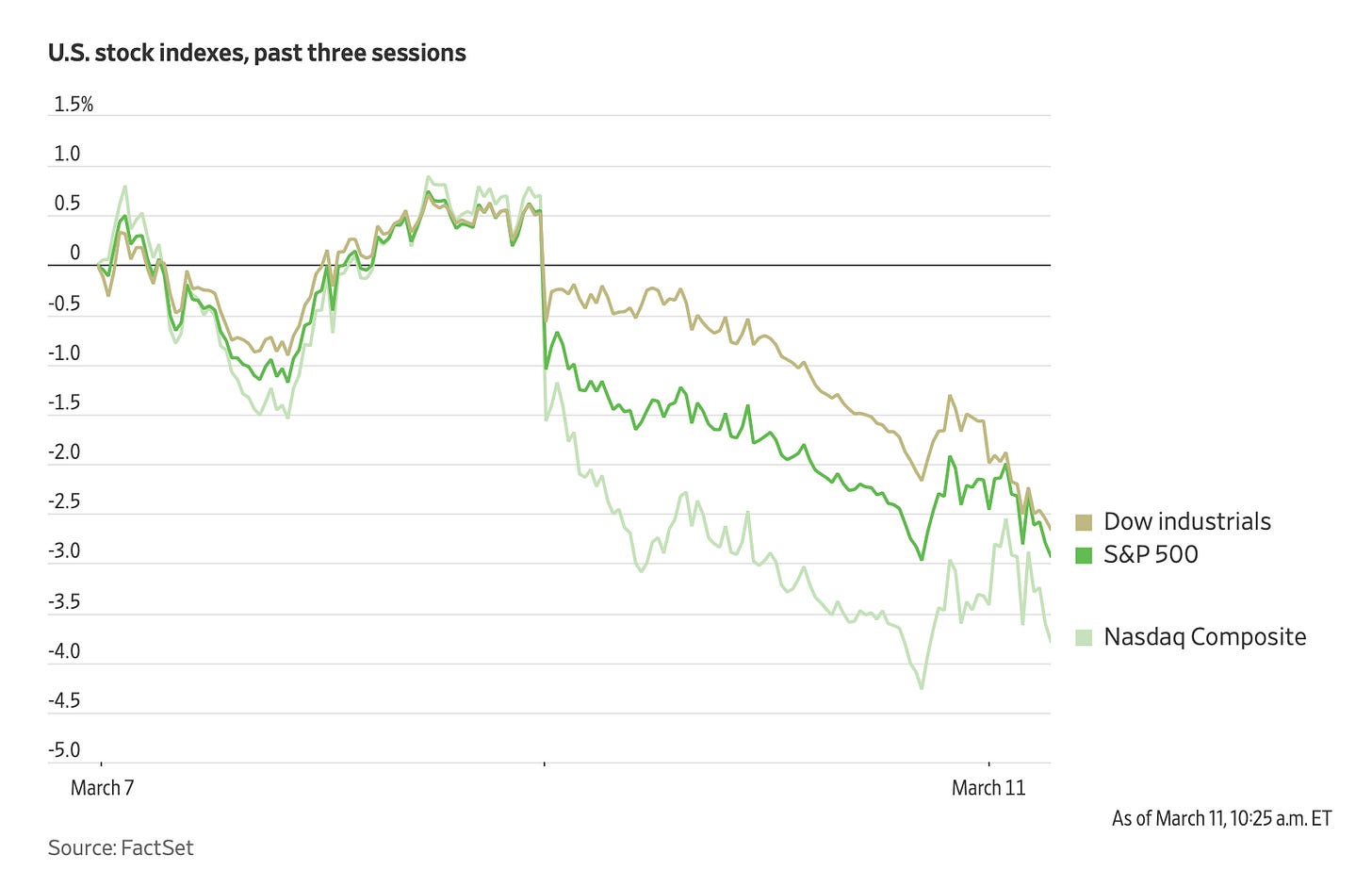

At least one group — investors — don’t seem to be pleased. At one point on Monday, the S&P 500 was on track for its worst day sine 2022; the index eventually recovered somewhat, but still ended the day with a 2.7% drop. The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed down 2.1%; the Nasdaq composite declined by 4%.

“It was the worst day yet in a scary stretch where the S&P 500 has swung more than 1%, up or down, seven times in eight days because of Trump’s on -and- off -again tariffs,” the Associated Press reported. “The worry is that the whipsaw moves will either hurt the economy directly or create enough uncertainty to drive U.S. companies and consumers into an economy-freezing paralysis.”

Sen. Rand Paul, a Kentucky Republican who has been critical of Trump’s tariffs, took to X on Monday night to suggest that the president pay attention. “The stock market is comprised of millions of people who are simultaneously trading,” Paul wrote. “The market indexes are a distillation of sentiment. When the markets tumble like this in response to tariffs, it pays to listen.”

Trump does not appear to have taken the warning to heart. This morning, he announced on Truth Social that steel and aluminum tariffs on Canada will double, from 25% to 50%, effective tomorrow. (Canada is the U.S.’ largest supplier of both metals.) He also threatened to “substantially increase” the tariffs on cars made in Canada next month.

The markets, which had started to recover some of their losses Tuesday morning, immediately began to plunge again after Trump’s post, as the specter of further uncertainty and higher prices moved back into the limelight.

Investors souring on Trump is all the more striking because, in his first term, booming markets were a point of pride for Trump, an indicator he paid close attention to. Now, a White House official dismissed the movements on Monday as “animal spirits,” a term used to suggest that investors are being driven by emotion instead of logic.

Beyond just the markets, rosy opinions of Trump’s economic stewardship — perhaps influenced by his years portraying a business titan on “The Apprentice” — have been one of his biggest political strengths for years now. Political analyst Amy Walter recently noted a fascinating turnaround: in his first term, Trump’s approval rating was deep underwater, but Americans generally rated his handling of the economy much more positively.

So far in his second term, Trump’s overall approval rating is higher — but opinions of his economic performance have precipitously dropped. Polling-wise, economic approval was once one of Trump’s few strong spots; now, more Americans disapprove than approve of how he’s running the economy.

If you’re wondering how opinions on Trump’s economic prowess — which also remained high during the campaign — could reverse so quickly, especially at the exact time that overall opinions on him have improved, here’s another chart for you.

Take a look at how the S&P 500 did at the opening of Trump’s first term, versus how it’s doing now:

“A period of transition”

The Wall Street Journal article accompanying that chart is all about worries that Trump’s tariffs will get in the way of the “soft landing,” a term for defeating inflation without sparking a recession, which most experts thought the U.S. was on track to do at the beginning of the year.

Of course, if it’s true that the economy was in good shape when Trump arrived, then that would explain why he spent less time talking about it at his first address to Congress than Clinton or Obama, who arrived during much less economically stable times.

But, remember: it’s not just about the economy, stupid. It’s about how people feel about the economy, and about how their leaders make them feel.

And, according to Gallup’s Economic Confidence Index, Americans felt worse about the economy on Election Day 2024 (an average of -26, on a scale from -100 to 100) than any election year in modern history except for… 1992 (-37), when Clinton won, and 2008 (-72), when Obama did. (In 2012, the index stood at -1, meaning Obama’s economic messaging allowed him to be the only incumbent party candidate on record to win the White House when the index was underwater.)

How Americans feel about the economy isn’t solely tethered to objective indicators, as seen in this New York Times graphic, comparing consumer sentiment to a prediction of where consumer sentiment would be based on certain data points:

Donald Trump successfully channeled that dissatisfaction into a victory last year, and then promptly appeared to forget how much his campaign relied on promises to lower prices.

As the Washington Post noted, out of his flurry of executive actions so far, one of the few to focus on combatting inflation was an order requiring his economic team to report to him within 30 days on steps they’d taken to reduce the cost of living. As of last week — 44 days after the order — the White House told the Post that no such report had been submitted.

They didn’t seem especially concerned about the oversight: “The president knows his plans,” a White House official told the Post. Meanwhile, of course, Trump has pursued policies that economists and the public both believe will increase prices.

The Obama example does show, however, that a president can succeed politically even without specific economic actions, if he focuses on molding public perceptions to his favor.

Here, too, Trump has dropped the ball.

Asked in an interview Sunday if he was expecting the U.S. to enter a recession, Trump didn’t exactly inspire confidence: “I hate to predict things like that,” he said. “There is a period of transition, because what we’re doing is very big. We’re bringing wealth back to America. That’s a big thing, and there are always periods of, it takes a little time. It takes a little time, but I think it should be great for us.”

Trump’s reference to a “period of transition” calls to mind yet another president who forgot his mandate: Joe Biden, who was elected to restore normalcy after Trump and instead decided to pursue an “FDR-sized” agenda — which was focused on economics, yes, but not on the issue that mattered most to Americans: inflation. There, Biden and his aides repeatedly promised that price increases would be only “transitory,” a comment that came back to bite them.

Americans, it turned out, were not too happy about the idea of accepting short-term pain in exchange for the promise of longer-term prosperity — exactly the trade Trump is promising them now.

Post-material politics

More than anything, what’s striking in Trump’s second-term economic rhetoric is how indifferent he seems about inflation, an issue that he talked about incessantly during the campaign.

He clearly loves discussing tariffs (“A beautiful word,” he said to Congress), but lowering prices doesn’t seem to hold the same luster. “They all said inflation was the No. 1 issue [of the election],” Trump said on his very first day in office. “I said, ‘I disagree.’ I think people coming into our country from prisons and from mental institutions is a bigger issue for the people that I know. And I made it my No. 1. I talked about inflation too, but you know how many times can you say that an apple has doubled in cost?”

Indeed, according to an Emerson College poll, Americans approve of Trump’s handling of immigration by eight percentage points. But they disapprove of his handling of the economy by eleven points, an even bigger margin. And, contrary to Trump’s comments, polls consistently show that the economy is the top issue for a plurality of voters. A recent CBS/YouGov survey found that 66% of the country believes Trump isn’t focusing enough on lowering prices.

At one point during the campaign, according to the Wall Street Journal, Trump complained to his aides that talking about inflation was “boring.” Here’s the headline of an article he recently shared on Truth Social: “Shut Up About Egg Prices — Trump Is Saving Consumer Millions.” That ought to do it.

There are shades here of 2011 Obama, wanting to move on from discussing the economy to focus on other issues (most of them highly charged social clashes). “I talk about the middle class all the time,” he groused when Axelrod told him he was losing focus, according to the strategist. How many times can you say that an apple has doubled in cost?

How is that president after president — elected largely to be responsible stewards of the economy — quickly forget that mandate and try to move on to other topics? It probably is partially due to the fact that presidents can’t always do much to improve the economy, so they prefer to focus on issues they can impact, even though the economy is where voters expect them to remain most attentive. (This would, however, at least call for presidents to hew to a “do no harm” principle on the economy, which Trump’s tariffs appear to be violating.)

Research by the late political scientist Ronald Inglehart would point to another factor. Inglehart predicted that as nations grow richer, their more prosperous citizens would stop rooting their politics in economic factors, instead adopting a “post-materialist” politics that was more focused on social clashes.

This theory may explain the U.S.’ turn towards a more culture war-infused politics in recent decades — as well as the fact that millionaire Obama and billionaire Trump, in different ways, appeared more animated by social than economic issues. Presidents occupy a very specific social stratum, surrounded by wealthy donors, peers, and consultants who presumably fall into Inglehart’s “post-materialist” category. They also must remain attuned to their party’s activist base (and associated media channels), which can further skew their perceptions on what issues Americans are focused on.

Recall Trump’s exact words: immigration, not inflation, was the top issue “for the people that I know.” But for a wider cross-section — even it turns out, those who are doing well economically by objective factors, but still feel like they are struggling, somewhat complicating Inglehart’s categories — inflation did and does predominate.

Trump, unlike Obama in 2011, never again has to run for re-election, freeing him up to focus on the issues that interest him, even if they don’t interest voters. But presidents, even lame ducks, are constrained by public opinion, as Trump’s term has already showed, and Trump’s legacy will likely require a Republican successor in 2028, who will be judged largely on Trump’s economy.

That means the smart thing for him and his party would be to change his tune on inflation, fast: tamping down concerns about a recession, trying to come up with actions that at least have the appearance of lowering the price of eggs and other products, and reinventing his messaging on tariffs (or deciding not to pursue them altogether).

Looking back, the most striking thing about the Obama anecdote isn’t that a president lost focus. It’s that his advisers told him so, and the president listened. The fate of Trump’s term could hinge on whether he, too, has aides willing to tell him “no” and to deliver similar warnings. The last few weeks would suggest they are in short supply.

This assumes Trump actually cared about any of the stuff he said to get elected. His real agenda was always to stay out of jail, get revenge, and enrich himself. He won - that’s all that matters to him.

To me it’s simple. More republicans voted than democrats. So he won. Does he have a mandate.……. NO. Will republicans excuse his behavior ….YES. Does he really care. …..NO. In fact, there has been a deep concern in my gut he is deliberately playing games and his real motives are revenge and that includes giving another tax break to the very wealthy, without regard for this country at all.