What Donald Trump Could Learn From Teddy Roosevelt

On the art of mediation.

Donald Trump has been elected president twice. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and a spot in the WWE Hall of Fame. He’s been named TIME’s Person of the Year.

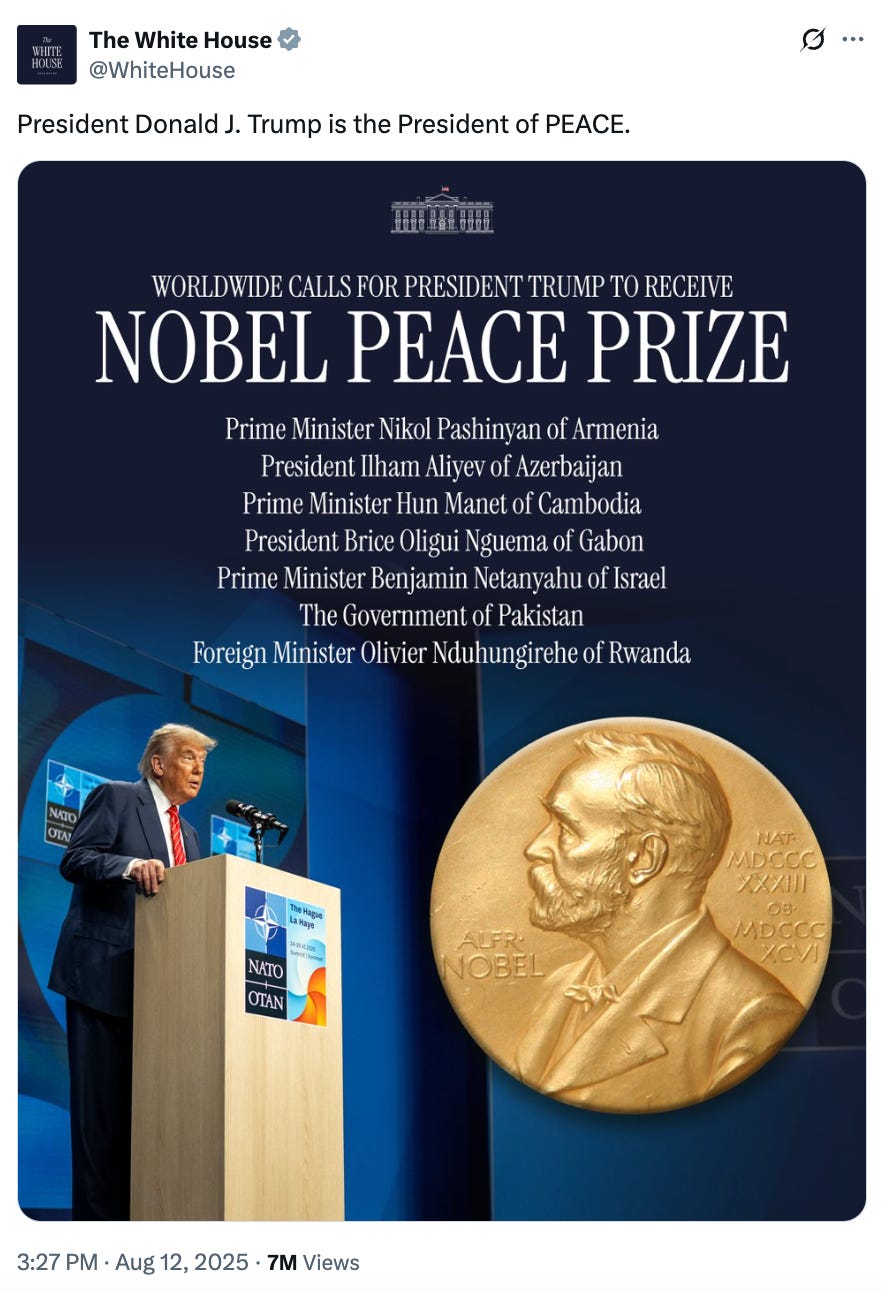

But lately Trump has had his eye on another accolade, the one that the Oxford Dictionary calls the most prestigious in the world: the Nobel Peace Prize.

As part of his campaign for the prize, Trump has claimed that he’s “stopped six wars” since taking office. (“I’m averaging about a war a month,” he said in July.) This claim lacks context: India has denied that Trump played a role in ending their dispute with Pakistan; the Israel-Iran war, which Trump also takes credit for resolving, ended as much because of American bombings as American peace talks.

Trump will travel to Alaska tomorrow to meet with Russian President Vladimir Putin in hopes of striking one more, undeniably-Nobel-worthy peace deal: an end to the war in Ukraine.

Four previous U.S. presidents have received the Nobel Peace Prize. Woodrow Wilson won it for founding the League of Nations after World War I. Jimmy Carter won it for his broader humanitarian work. Barack Obama won it for—well, nobody’s entirely sure why.

Theodore Roosevelt, the first American to win any Nobel, is the only president to receive the Peace Prize specifically for what Trump wants one for: ending a war.

In fact, that conflict also included Russia as one of the combatants: it was the Russo-Japanese War, which was fought from 1904 to 1905 over the two empires’ expansionist ambitions in Asia.

Just as the Russia-Ukraine War has sometimes been said to be ushering the world into a new era of warfare, with its use of drones, AI-powered weapons, and cyberattacks, the Russo-Japanese War is often considered “the first modern war,” due to its early use of industrialized weaponry. Some scholars even call it “World War Zero,” a nod to how it presaged the conflicts that would come later in the century.

From there, the parallels work best in reverse. While Russia is the one that attacked Ukraine in the current conflict, it’s Japan that made the first move towards war against Russia in the 20th century dispute. The contexts are also different: the Russo-Japanese War was fought over the broader reaches of their empires, unlike the Russia-Ukraine War, in which Ukraine’s own sovereignty is at stake.

Regardless, some lessons are still available to Trump from Roosevelt’s successful mediation of the conflict.

For one thing, both would be considered unlikely peacemakers: men more known for their bellicosity than their diplomacy. When Roosevelt was given the Nobel Peace Prize, the New York Times archly wrote that it was being awarded to “the most warlike citizen of these United States.” (It was less than a decade before that TR had helped push the U.S. into the Spanish-American War.) Surely, similar complaints would follow any move by the Nobel Committee to recognize Trump.

But Roosevelt’s aggressive personality, like Trump’s, lent itself to an unorthodox negotiating style, which — at least in TR’s case — ended up working in his favor. Too impatient to go through the normal channels, Roosevelt preferred to negotiate with other leaders directly, running American diplomacy with only the help of his “Tennis Cabinet,” just as Trump has deployed his golf buddy Steve Witkoff to every global hotspot under the sun.

Roosevelt was fascinated by foreign affairs, and loved to be in the middle of things — he “wanted to be the corpse at every funeral, the bride at every wedding and the baby at every christening,” his daughter said — which is how he found himself at the center of the Russo-Japanese negotiations.

Towards the beginning of the war, he was more sympathetic towards Japan (the more aggressive side), but as the conflict ground on, he tried to stake out a more neutral position, worried about Japan seizing too much power.

Sound familiar so far?

But Trump should take note of how Roosevelt handled the Russo-Japanese peace process, which TR guided, his biographer Edmund Morris wrote, “by sheer force of moral purpose, by clarity of perception, by mastery of detail, and benign manipulation of men.”

He grounded himself in the minutiae of the process, from the location of the talks — which convened in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, at his invitation — to the details of each side’s demands. On the eve of the summit, Roosevelt sat down, separately, with the Russian and Japanese envoys to urge them to sand down their demands, hoping to get them as close to each other as possible before they even entered a room together.

Monitoring the negotiations from nearby New York, but frequently sending telegraphs to Portsmouth and beyond with his advice — “a one-man electrical storm of cables to St. Petersburg, Peking, Paris, London, and Tokyo,” Morris describes it — Roosevelt continued to urge both sides to moderate, which he framed as being in their best interest and the interest of the world.

“Ethically it seems to me that Japan owes a duty to the world at this crisis,” the American president wrote Japan’s envoy. “The civilized world looks to her to make peace; the nations believe in her; let her show her leadership in matters ethical no less than matters military. The appeal is made to her in the name of all that is lofty and noble; and to this appeal I hope she will not be deaf.”

“I speak as the earnest well-wisher of Russia and give you the advice I should give if I were a Russian patriot and statesman,” Roosevelt wrote the Russian emperor. Slowly, but surely, the Treaty of Portsmouth came together, with concessions not unlike what TR had urged both sides to accept all along.

Roosevelt’s centrality in ending the war between two empires would help cement America’s role on the world stage going into the 20th century. It was the “last time,” according to the historian Eugene Trani, that “a great international dispute proved susceptible to personal arrangement.”

Trump, like Roosevelt, has cast himself as a neutral arbiter in the current conflict. There is a virtue in this, and it could theoretically allow him to push both Russia and Ukraine towards making concessions that a Joe Biden or Kamala Harris might never have been able to, because they had no relationship with one side and an ideological opposition to exerting too much pressure on the other.

But Trump seems to have a very different conception of neutrality than Roosevelt. To Roosevelt, it meant pushing both sides, urging them to drop a demand here or accept a concession there. Trump’s image of neutrality more often seems like it means agreeing with both combatants, inevitably telling them what they want to hear, without much consistency between his positions.

Just in the last 24 hours, Trump has bounced all over the map on what the Putin talks will bring. Not only has he tried to lower expectations — what was once a path to peace has now become a “feel-out meeting” — he has also seemed to change his mind on the contents of the talks. After saying Monday that he and Putin would be discussing “land swapping,” Trump reportedly told Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and other European leaders Wednesday that possible divisions of territory will not be on the agenda.

Trump is also said to have told the Europeans that the U.S. is willing to contribute security guarantees for Ukraine, despite previously saying otherwise.

At several stages, Trump has come close to using a Rooseveltian “big stick” against both Russia and Ukraine, in order to get each side in line — threatening to pull intelligence support for Ukraine, and to impose sanctions against Russia. So far, at least, he’s been pulled back from the brink each time, seeming to take the side of whichever leader he speaks to last.

Unlike Roosevelt, Trump has “shown little interest in the specifics of a deal,” according to the Wall Street Journal, which is reflected in how often he seems to change his mind about the potential agreement.

Flexibility can be useful in a negotiation, but less so if it comes without any set of consistent asks or guardrails — if an aspiring peacemaker is in search of a deal, above all, without any attention to what it will entail. Then, a mediator runs the risk of being sweet-talked by each side, with both combatants claiming they are the ones that truly desire peace — who can deliver A Deal, just as the mediator wants! — leading the mediator to believe one, then flip to believing the other, nodding along more than exerting pressure once he steps into a room.

That’s what many European leaders fear will happen tomorrow in Alaska.

Here, Roosevelt’s Nobel Lecture — belatedly delivered in 1910, four years after he was awarded with the Peace Prize — is instructive.

“Peace is generally good in itself, but it is never the highest good unless it comes as the handmaid of righteousness,” Roosevelt said. “And it becomes a very evil thing if it serves merely as a mask for cowardice and sloth, or as an instrument to further the ends of despotism or anarchy.”

A peace deal is something to shoot for, Roosevelt told his crowd. But peace isn’t everything, he added, a somewhat subversive thing to say to the people who just gave you a peace prize. “We must ever bear in mind that the great end in view is righteousness,” he added. A deal is only the means to an end, not the end itself.

As he travels to Anchorage, Trump would do well to remember these words. It is good to strive for a peace deal — but viewing it as your ultimate end will make it hard to strike one. Away from either Putin or Zelensky, Trump should take time to consider what he views as the most righteous (yet achievable) outcome in the war, and then try to push both sides towards it, rather than viewing a deal as the ultimate goal and then accepting each side’s proposed agreement without scrutiny.

Who knows if it will win him a Nobel — but, hey: it worked for Roosevelt.

One big problem is that Trump wouldn't know righteousness if it came up to him, introduced itself multiple times and whacked him on the head with the Epstein files 😅

An insightful, thoughtful overview of TR and how he truly earned his Nobel Prize. Trump won't learn anything from this great president, but I learned a lot reading this post. Thank you.