This Century-Old Tool Enabled the Epstein Vote. It’s Having a Renaissance.

Welcome to the nerdiest take you’ll read about the Epstein Files.

This week, a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers banded together in a grassroots effort to force a House vote that would embarrass President Trump.

I’m referring, of course, to the resolution “providing for consideration of the bill (H.R. 2550) to nullify the Executive Order relating to Exclusions from Federal Labor-Management Relations Programs, and for other purposes.”

Oh, you thought I was talking about the Epstein files?

Actually, yesterday’s lopsided House vote to release documents related to Jeffrey Epstein wasn’t the week’s only example of Republican lawmakers breaking with Trump by triggering a vote that he and GOP congressional leaders didn’t want to happen.

On Monday, Rep. Jared Golden (D-ME) announced that he had notched his 218th and final signature on a separate discharge petition, a tool that can jam a bill onto the House floor over the objections of the speaker if a majority of House members sign on. The underlying measure would repeal an executive order issued by Trump in March that ended collective bargaining rights for federal workers at agencies with “national security missions”; the order prevents about two-thirds of federal employees — working everywhere from the Departments of State and Defense to the EPA and FDA — from joining unions.

The discharge petition to overturn the order was signed by 213 Democrats and five Republicans: Reps. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA), Don Bacon (R-NE), and Robert Bresnahan (R-PA), plus Reps. Nick LaLota (R-NY) and Mike Lawler (R-NY), who signed the petition on Monday, putting it over the top.

“America never voted to eliminate workers’ union rights, and the strong bipartisan support for my bill shows that Congress will not stand idly by while President Trump nullifies federal workers’ collective bargaining agreements and rolls back generations of labor law,” Golden said in a statement.

In our political system, 536 people — 435 representatives, 100 senators, one president — are given a chance to weigh in before a bill becomes a law.

But, in reality, three of those figures wield outsized sway: the speaker of the House and Senate majority leader typically control the floor schedules for their chambers, while the president alone is bestowed with the veto power (as well as considerable influence over the legislative agenda when his party controls Congress).

It takes a rare uprising by the rank-and-file for those three people to oppose (at least until recently) a piece of legislation, and to still see it become law.

Most famously, that’s about to happen with the Epstein Files Transparency Act, a bill requiring the attorney general to release “all documents and records in possession of the Department of Justice relating to Jeffrey Epstein.” The bill reached the House floor on Tuesday, as a result of another successful discharge petition, and ultimately passed in a 427-1 vote. (Rep. Clay Higgins, a Louisiana Republican, was the lone dissenter.) The Senate then voted unanimously to preemptively approve the bill before it was even formally transmitted by the House. After a long wait, and then a stunningly quick ending, the measure will soon be headed to President Trump’s desk, where he has said he will sign it.

That chain of events was obviously notable for all sorts of political reasons, some of which I covered on Monday and will again. But when put together with the successful Golden petition, the Epstein vote also carries notable implications for Congress, as lawmakers who have increasingly handed over power to their leaders in recent years show signs of reasserting themselves.

And these aren’t even the only examples this year: the current Congress, which convened in January, is now the first in 75 years to see three discharge petitions reach 218 signatures, a striking revolt of the rank-and-file against the speaker.

The discharge petition is a quintessentially (small-d) democratic tool, a device that allows a majority of House members to rise up and assert their will against congressional leadership (and, in both the Epstein and federal union cases, a president who sometimes seems to moonlight as a congressional leader).

“It’s a great thing that this institution has that legislative vehicle,” Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY), who led the Epstein discharge petition, told me of the procedural tool on Tuesday. “It’s the fuse in the fuse box, when everything gets jammed up and the wires get crossed and nothing can get done. If something needs to get done, it can happen.”

Despite this power — or perhaps because of it — the discharge petition laid dormant for most of the 21st century. From my vantage point in the press gallery Tuesday, I watched as Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) referred to the discharge petition on the Epstein files as “perhaps the most famous discharge petition in history.”

That statement may be true — there’s no doubt that the Epstein files have inspired enormous public attention — but it also potentially represents a short historical memory. Discharge petitions have been at the heart of some of the most consequential legislative battles in our nation’s history.

As I noted in August, America’s first federal minimum wage ($0.25 an hour) was instituted in 1938 as a result of a successful discharge petition. (The underlying measure, the Fair Labor Standards Act, was the first bill to become law using this route.) A discharge petition with 218 signatories also made possible the McCain-Feingold Act of 2002, the most significant campaign finance reform law in recent history.

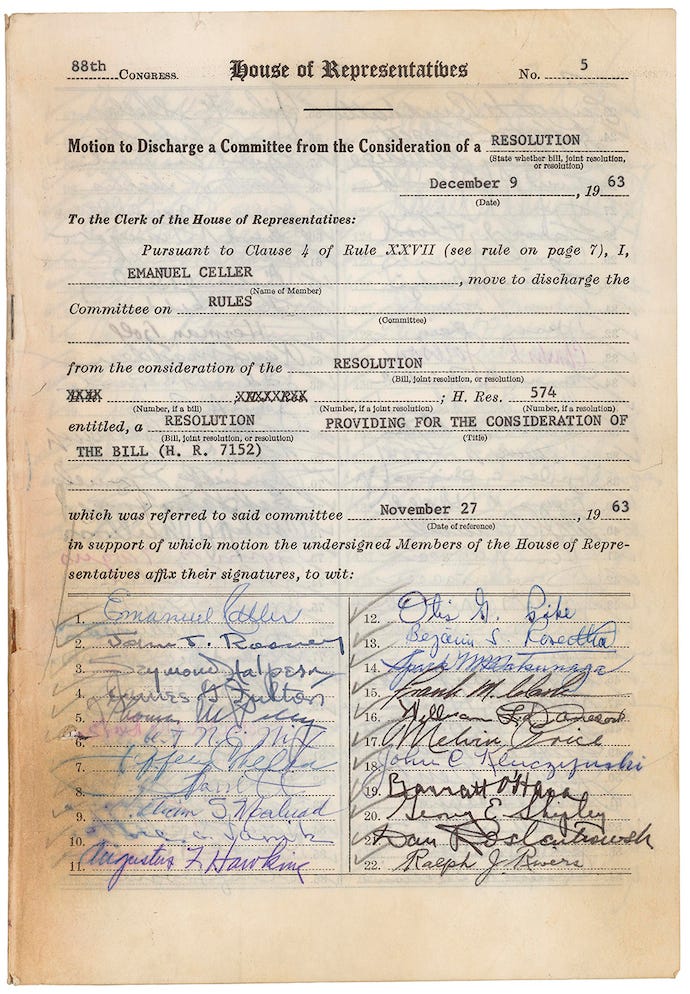

The landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 also arguably owes its passage to a discharge petition; even though the petition for that bill didn’t notch the sufficient signatures, it was the fact that it was about to reach that threshold that persuaded Southern congressional leaders to allow a vote on the legislation. (Not unlike how Speaker Mike Johnson eventually came around to supporting the Epstein bill this week. In both cases, congressional leaders reasoned that, if something was going to happen anyway, they would rather allow it to happen on their terms than suffer the public humiliation of it taking place against their will.)

Not all successful discharge petitions have made history: one in 1948 was for a bill to repeal taxes on margarine; another in 1980 exempted soft drink companies from antitrust law. But several were the subject of public pressure campaigns just as intense as that over the Epstein files — if not more.

During the drawn-out fight over the Civil Rights Act, for example, President Lyndon Johnson “engaged an army of lieutenants—businessmen, civil-rights leaders, labor officials, journalists, and allies on the Hill—to go out and find votes for the discharge petition,” as the Atlantic reported.

In 1932, more than 40,000 protesters descended on Washington to demand relief for World War I veterans in the midst of the Great Depression; the group, known as the “Bonus Army,” set up an encampment in the nation’s capital until they were violently removed at the behest of President Herbert Hoover, an event that shocked the public and dominated public debate for months.

Ultimately, it was a discharge petition that moved a bill to meet the veterans’ demands onto the House floor, despite the objections of House Republican leaders. (The measure then passed the House, but not the Senate.) Throughout the fight, one historian has written, the Bonus Army closely tracked the signatures on the discharge petition and “made daily walks to the Capitol to convince Congressmen” to sign it.

Six years later, Congress witnessed a popular crusade relating to the Ludlow Amendment, a proposed constitutional amendment that would have required a nationwide vote every time the U.S. declares war, unless we were attacked first. The text of the proposal is rather direct:

Except in the event of an invasion of the United States or its Territorial possessions and attack upon its citizens residing therein, the authority of Congress to declare war shall not become effective until confirmed by a majority of all votes cast thereon in a nationwide referendum. Congress, when it deems a national crisis to exist, may by concurrent resolution refer the question of war or peace to the citizens of the States, the question to be voted on being, Shall the United States declare war on ________?

That may sound fantastical today (in the modern era, not even Congress really decides when we’re at war, much less the public), but it was overwhelmingly popular in the 1930s, as isolationism and fear of war gripped the country. At one point, a Gallup poll found that 75% of Americans backed the proposed amendment.

President Franklin Roosevelt and his Democratic deputies in Congress naturally opposed the idea, however, which meant it was — you guessed it — a discharge petition that jammed the measure onto the House floor. (It failed to receive approval, since even though it notched the simple majority needed for a discharge petition, that was still short of the two-thirds majority needed to amend the Constitution.) The 1938 fight also received significant public attention, mobilizing religious, pacifist, and education groups in support of the amendment.

Discharge petitions for the Equal Rights Amendment and a Jim Crow-era anti-lynching bill similarly inspired large public interest.

It should be no surprise that the Epstein discharge petition is far from the first to move forward due to mass public pressure (and to enable rejection of a president, as seen in the Hoover and FDR examples), since it is one of the more populist tools in the lawmaker’s arsenal. (Indeed, the process was first created in 1910 as part of a rank-and-file revolt against a tyrannical House speaker.)

Massie boasted to me Tuesday that only 4% of discharge petitions prove successful (or at least that’s what the AI tool Grok told him, he said). When I asked what allows a petition to become part of that exclusive club, he answered: “A slim majority, a populist movement, and an issue where it’s black and white, and nobody wants to debate the other side.”

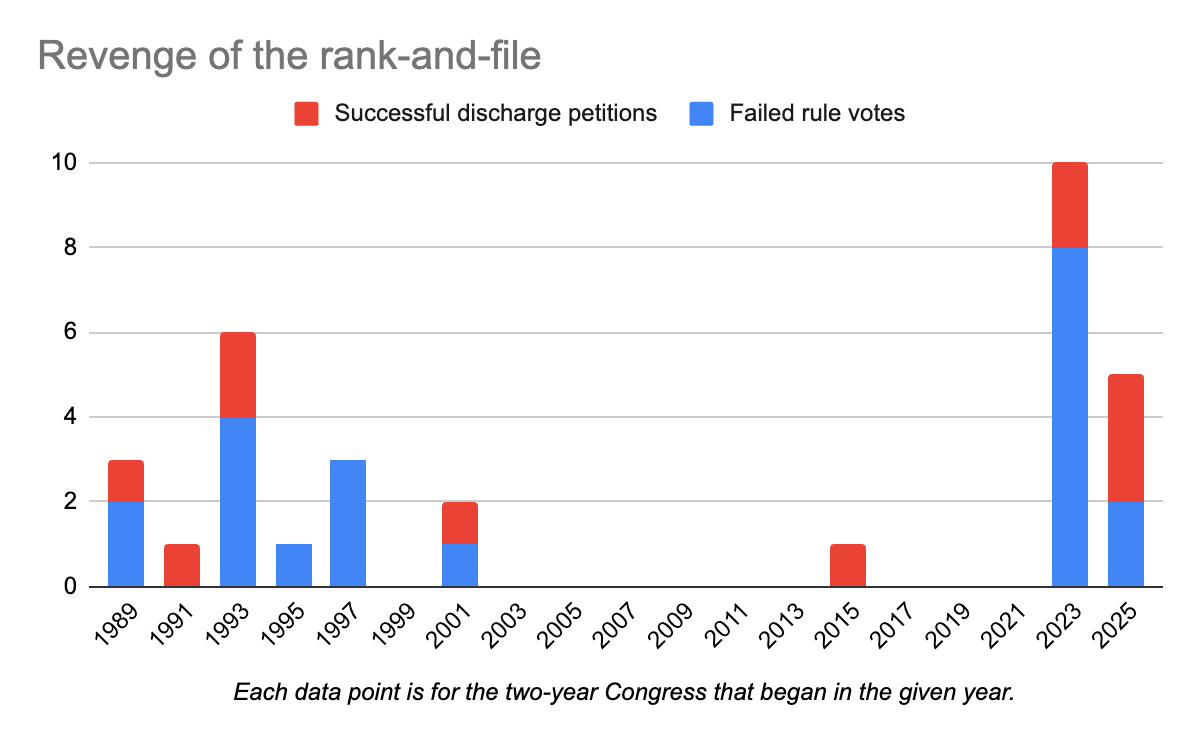

It makes sense, then, that in our populist era discharge petitions would see a revival. In the last two years, almost triple as many discharge petitions have notched 218 signatures as did so in the first 23 years of the 21st century.

Between 2000 and 2023, as power increasingly concentrated in the hands of the House speaker, only two discharge petitions reached the majority threshold: McCain-Feingold in 2002, and a bill reauthorizing the Export-Import Bank in 2015. In many of these years, not a single discharge petition was even initiated.

In 2024 and 2025 alone, five discharge petitions have successfully pushed bills onto the House floor. That includes two in the last Congress: bills offering tax relief for people hit by natural disasters, and expanding Social Security benefits for public employees, both of which were ultimately passed by sweeping bipartisan majorities and signed into law by President Joe Biden.

And then there are the three this year: the Epstein bill, the federal union bill, and a discharge petition by Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-FL) that reached 218 signatures in March to change the House rules to allow new mothers to vote by proxy. (Luna eventually struck a deal with Johnson, enacting a compromise version of the rule.) The last Congress to see a speaker overruled thrice by discharge petitions was the 81st Congress, which met from 1949 to 1951.

As lawmakers left the Epstein vote yesterday, I canvassed them on why the pace of discharge petitions has skyrocketed.

Most Republicans didn’t want to answer: the normally voluble Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), one of the four Republicans to sign the Epstein discharge petition, demurred. “I don’t know!” replied Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-NC), who chairs the House Rules Committee. (The Rules Committee is the organ used by the speaker to set the floor schedule, so the discharge petitions also double as a rejection of Foxx.)

Rep. Mike Lawler (R-NY), who provided the critical 218th signature this week for the discharge petition on federal unions, told me that he didn’t think there was anything specific to this Congress that explained the increase.

“I think it ebbs and flows,” he shrugged. “It just depends on the situation.”

But Democratic lawmakers see it differently. “We have a majority that doesn’t want to govern, and more importantly, they do not know how to govern,” Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) told me.

“Republicans have just been following the president instead of the people’s constituents, and that leaves vulnerable Republicans in a very difficult place where there’s no negotiation going on — on anything,” Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) said. “And so the only way to get something to the floor then, in that situation, is to file a discharge petition.”

Massie, who has repeatedly broken with Trump and Johnson, appeared to agree with this diagnosis. “Because he’s not giving an outlet for legislative pursuits, the things we got elected to do, he’s probably going to see more of these discharge petitions,” Massie told reporters, referring to Johnson.

Discharge petitions also carry more weight in an era of slim majorities, because that means it only takes a few defections from the majority party for the tool to be successful. They aren’t the only tool we’ve seen the Republican rank-and-file use to this effect. The normal path for bills to reach the House is through what’s known as a “rule,” a resolution passed by the Rules Committee that empowers the House to debate and vote on a given piece of legislation.

Rules also have to pass the full House before a bill does, but these are usually pro forma votes: until recently, it was considered a shocking departure for members of the majority party to vote against their leaders on a rule. Notably, this held true even if a member opposed the bill being set up for debate: that’s how important it was considered that majority party leadership preserved control of the floor schedule.

Like discharge petitions, it was essentially unheard of for most of the 21st century for a majority party to sink a rule vote — until Republicans won back the House in 2022, and both procedural tools started to be used after decades of fading into obscurity. (Democrats have also seen their own rank-and-file uprisings in recent days, as one Democratic lawmaker moved to rebuke another over his apparent attempt to secretly hand his seat to a top aide.)

Several members I spoke to on Tuesday said that this year’s run of successful discharge petitions may not be over.

Jayapal raised the prospect of a discharge petition on a congressional stock trading ban — an issue that would fit comfortably within the discharge petition’s history of unlocking populist pursuits, and furthering bills where lawmakers police themselves (like the McCain-Feingold campaign finance reform) that are opposed by leadership and other veteran members.

Rep. Anna Paulina Luna, who has already championed one discharge petition this year, told Politico that she plans to introduce a discharge petition on a bipartisan stock trading ban for lawmakers if leadership doesn’t announce a committee vote on the measure today.

“Oh yeah,” Massie replied when I asked if he has more discharge petitions in the works as well — though he declined to name them. “We’re brainstorming,” the Kentucky congressman told me.

Perusing lists of pending bills with numerous cosponsors, several potential candidates emerge. A bipartisan bill expanding Medicare coverage for multi-cancer early detection screening tests currently boasts 332 supporters but has yet to receive a floor vote; another to boost funding for rape crisis centers and domestic violence shelters has been lingering despite its 321 cosponsors.

The Give Kids a Chance Act, which seeks to increase drug research for rare pediatric diseases, came close to passing last year, before a funding bill it was part of was blown up by Elon Musk. (I profiled the bill’s author last year.) It now has 313 cosponsors, more than enough to pass if it were to be given a vote. Measures imposing Iran sanctions and “expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that Congress should take all appropriate measures to ensure that the United States Postal Service remains an independent establishment of the Federal Government and is not subject to privatization” — a not-so-subtle dig at an idea floated by Trump — also have more than 218 backers but no immediate path to a floor vote.

In the Senate, a bill imposing sanctions on Russia is backed by 84% of the chamber but has not received a vote because Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) is waiting for Trump’s say-so. In the upper chamber, there’s no equivalent of discharge petitions — and there’s actually no need. Under certain circumstances, any member can technically move to proceed to a piece of legislation, although senators from both parties, by courtesy, reserve this power for the majority leader. (Individual senators broke this custom on at least two recent occasions, in 2020 and 2023, however.)

Even though discharge petitions would technically be superfluous in the Senate, perhaps the chamber should adopt them — offering a formal way for a majority of senators to force something onto the floor, without launching a frowned-upon sneak attack against the majority leader?

After all, it’s somewhat strange — to take the Epstein bill, for example — that a piece of legislation could apparently be supported (once it’s put to a vote, at least) by 99% of Congress, but could go months without advancing simply because congressional leaders won’t allow it.

It would potentially cause chaos if every time shifting majorities of 218 House members and 51 senators supported a bill, it was guaranteed a vote. (Though what’s democracy if not chaos?) But with public approval of Congress at an all-time low — and a surprising array of bills boasting majority support, but unable to reach the floor — perhaps it should be made slightly easier for bills with broad, bipartisan support to become law.

Using (and expanding) the discharge petition is one way to do this: both by adopting them in the Senate, and by implementing proposals in the House that would allow entire committees to more easily discharge bills to the floor if they have bipartisan work products that are being passed over by the speaker. Then again, House members right now seem to be using discharge petitions just fine all on their own.

The powerful tool that helped give us a minimum wage, the Civil Rights Act — and now the Epstein files — may have gone into a long hibernation, but it’s far from extinct yet.

Love my civics class!

Always. Always good to know that I would never had known if you hadn’t presented this topic!! Thanks!!