The House Is On An Unprecedented Recess

Our temporarily unicameral legislature.

Since the government shut down on October 1, the U.S. Senate has held 63 roll call votes.

Eleven of those votes have been on the Republican-backed continuing resolution, which is now believed to have received more cloture votes than any bill in Senate history. But the chamber has also found time to approve a massive, 3,000-page defense bill, a resolution overturning President Trump’s Brazil tariffs, and legislation covering everything from paid leave to manufacturing. Plus, the Senate has confirmed nine federal judges and 109 other Trump nominees (most of them in one large batch) this month.

Senators may still be struggling to strike a spending deal, but you can’t say they haven’t been working on a range of policy matters throughout the shutdown.

How many votes has the House held over the same period? Zero.

House Speaker Mike Johnson has kept his chamber away from Washington since the beginning of the shutdown. In fact, since the House was on a pre-scheduled break before the funding gap began, the lower chamber has now gone 41 days without holding a single vote (ostensibly, its main purpose as a legislative body). The last House vote took place on September 19, on a resolution honoring Charlie Kirk. Because the chamber also spent all of August and part of July out of town, it has only held regular sessions on 12 days out of the last 100.

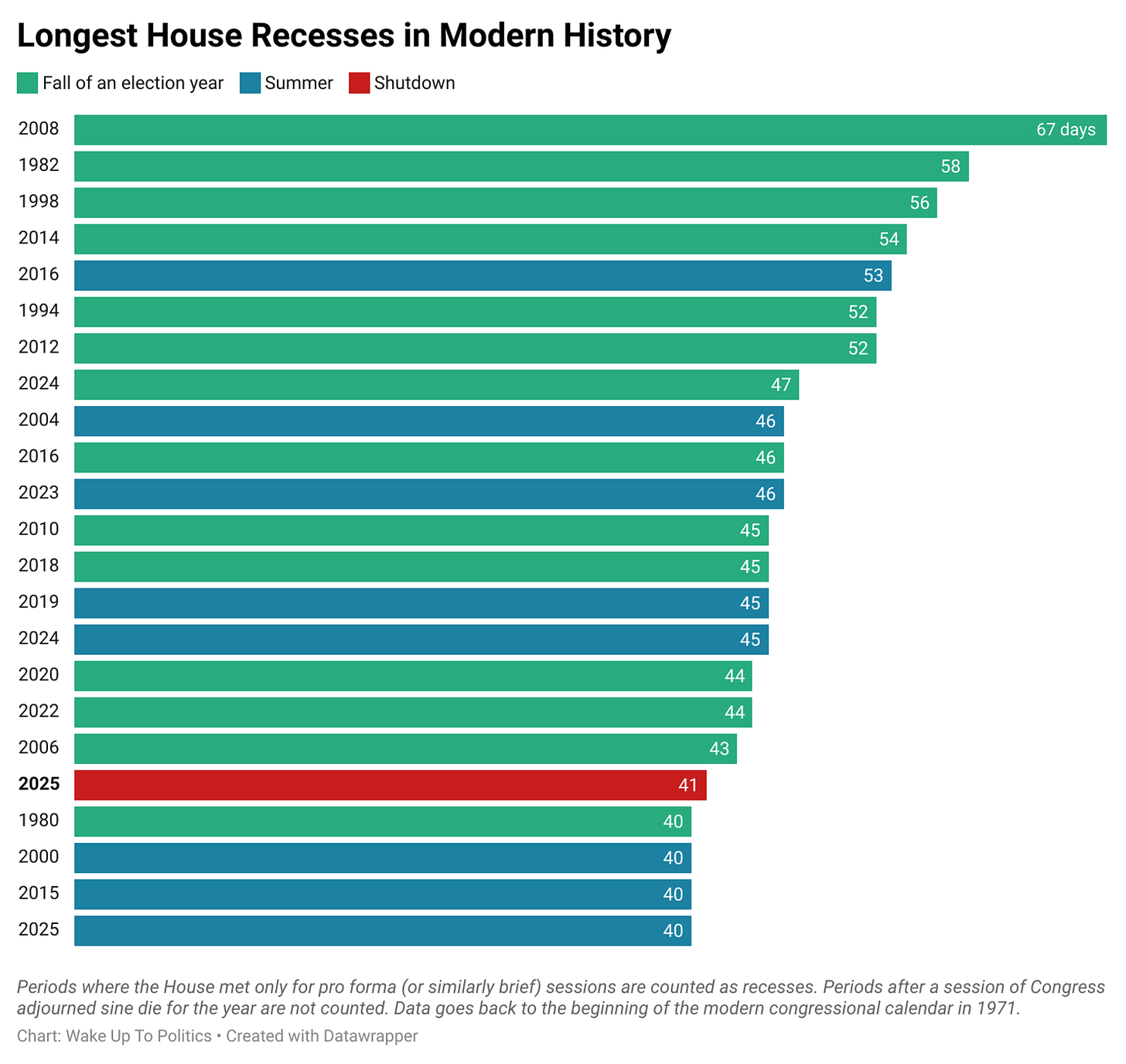

There is no parallel for a break of this kind and length in modern House history.

According to a Wake Up To Politics analysis, since the advent of the modern congressional calendar in 1971, the House has gone through 22 periods where it’s left for recess for 40 days or more.1

All but one fall into the normal cadence of the congressional calendar. Eight were for the chamber’s regular summer recess; 13 were due to the House’s longstanding practice of recessing during the fall of an election year, to allow members to campaign. We are currently living in the single outlier: the only time in the last five decades that the House has left Washington for 40+ days outside of summer or campaign season.

There’s nothing that says a chamber of Congress has to recess like this during a shutdown (as you can tell by looking at the Senate). If anything, members of the House are some of the few officials in the U.S. government who continue to receive paychecks during a funding gap, which would make one think that they might continue working on legislative business during the shutdown.

Of course, just because they’re on recess, it doesn’t mean House members aren’t working at all. In fact, Speaker Johnson said Monday that “House Republicans are doing some of the most meaningful work of their careers” while back in their districts, helping constituents negotiate the impact of the shutdown. “I don’t want to pull them away from that,” he said. (According to an item in Politico, many House Republicans have been “picking up new hobbies while waiting out the shutdown,” including “discovering the advent of electric leaf blowers.”)

Johnson has repeatedly said that the House has “done its job” by approving a clean CR, which means the ball is in the Senate’s court and there’s no point bringing representatives back to Washington. That’s fair enough as far as working to resolve the shutdown goes, but there are still many things that House members could have done in the last 41 days, which represents 5% of the two-year terms they were elected to.

There are currently 144 bills that have been approved by committees and are pending on the House floor, any of which the chamber could take up if it reconvened. These include measures concerning rural access to health care, veterans with PTSD, sanctions on Russia, and numerous other issues.

If the House were in Washington, committees would also be able to continue working, holding hearings and advancing new pieces of legislation. In addition, the chamber could also be looking beyond the shutdown: even after a continuing resolution passes and the funding gap ends, full-year appropriations bills will still need to be approved to enact permanent spending levels for Fiscal Year 2026 (or the 11 months that remain of it, at least).

So far, the House has only passed three of the 12 appropriations bills for FY 26 (Defense, Energy/Water, and Military Construction/Veterans Affairs). The chamber could be using this time to work on the other nine, thus shoring up its position for negotiations with the Senate and getting a head-start on the broader government spending fight that the current shutdown is just a prelude to.

Then again, bringing the House back would almost certainly bring headaches for Johnson: if Republican lawmakers were physically in Washington, it would increase the odds that they drift off-message, or that they start questioning his shutdown strategy. Some might push for negotiations with Democrats; others might advocate for holding votes on reopening the government piecemeal, an approach Republican leaders have dismissed. There have already been intraparty clashes over the phone on whether to return to Washington; Johnson hardly wants in-person skirmishes among his members.

“Emotions are high. People are upset — I’m upset. Is it better for them, probably, to be physically separated right now? Yeah, it probably is, frankly,” Johnson said earlier this month, defending his prolonged recess. (Not exactly the most confidence-inspiring assessment of the maturity of members of Congress! Adjourning indefinitely is the only way to stop them from lashing out at each other?)

A return to Washington would also mean a swearing-in ceremony for Rep.-elect Adelita Grijalva (D-AZ), who won her seat in a special election on September 23, but whom Johnson has declined to swear in until the House reconvenes for a regular session. (Procedurally, there is nothing preventing a swearing-in from taking place right now if Johnson were to consent; as recently as this year, he’s sworn in members during periods when the House wasn’t meeting in regular session. Grijalva now holds the record for the longest delay in a member of Congress being sworn in after a special election.)

Once Grijalva is seated, though, she is poised to become the 218th signature on a discharge petition forcing a vote on releasing the Jeffrey Epstein files, a measure opposed by Trump and Johnson. Some Democrats say this explains the chamber’s extended absence.

Several of the committee-passed bills the full House could be voting on right now would advance agenda items of President Trump’s, including combatting crime, preventing gender surgeries for minors, boosting border protection, addressing the threat posed by the gang Tren de Aragua, and halting production of the penny. “I have no respect for the House not being in session passing our bills and [codifying] the President’s executive orders,” Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) wrote this week on X.

But the president himself seems perfectly fine with the fact that the House is rendering itself unable to vote on his priorities, appearing content to have Washington to himself (minus the pesky Senate), tackling those issues by executive fiat, instead of with legislative input. Trump hasn’t pushed the House to return in order to enact more of his legislative agenda — largely because he doesn’t seem to have one. “We don’t need to pass any more bills,” Trump told lawmakers at the White House last week, asserting that “we got everything” done in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act that was passed this summer.

Trump reportedly enjoys the fact that the House has shrunken into more of a presidential plaything — brought out of its box only when he wants to use it — than a fully functioning branch of government. “I’m the speaker and the president,” he’s joked, according to the New York Times.

This long break has been made possible because of a 2023 rules change, which gave the House speaker the unilateral authority to designate “district work periods,” which are times (like now) when the House is effectively on recess, only meeting every three days for pro forma sessions, where one member gavels the chamber in and then gavels it out a few minutes later. Previously, a vote of the full House was required to initiate a district work period.

Because of this new power, as long as the speaker — and, under the current arrangement, the speaker-president — want to keep the House out of session, they can.2

Eventually, even if the shutdown stalemate continues, the House will have to return. The House-passed continuing resolution that the Senate keeps voting on would only fund the government through November 21. In a worst-case scenario where the shutdown lasts another three weeks, Johnson will have to call the House back, if only to give the Senate a new clean CR to vote on.

But Johnson doesn’t seem prepared to do that — at least not yet. “Wouldn’t that be a futile exercise when we have a CR that’s been sitting over there since September 19?” Johnson said yesterday. “If I brought the House back and we passed another CR, it would meet the exact same fate from Chuck Schumer. He would mock it. They would spike it. And they would try to blame it on us. So what would be the point of that?”

And so, a recess like no other continues, turning the U.S. Congress (at least temporarily) into an effectively unicameral legislature.

In researching this piece, I combed through legislative schedules and issues of the Congressional Record dating back to the 1940s, trying to find any sort of parallel where the House had simply stopped voting for this long in the middle of the year, outside of summer or the fall of an election year. I was able to find two periods (January-February 1963 and January-February 1979) where the House went more than 40 days without holding any roll call votes — but during both of these stretches, the chamber continued to meet for regular, hours-long sessions, debating legislation, holding voice votes, and gathering at the committee level (none of which is happening now).

Expanding my aperture a bit beyond the 40-day mark, the closest parallel available is the stretch from March 14 to April 23, 2020: when the House recessed for 39 days at the start of the Covid pandemic. To the House, the shutdown is apparently akin to a medical emergency, requiring social distance and preventing lawmakers from convening in one place.

Outside of pre-scheduled breaks for summer and campaigning, a global pandemic provides the only modern precedent for the House refusing to work in Washington for such an extended period. And, even then, that recess didn’t last as long as this one.

Here, I’m defining “recess” as periods in the middle of the year where the House goes without meeting in regular session. Periods after a session of Congress has adjourned sine die for the year are not included. Periods where the House meets only for pro forma sessions (or similarly brief sessions lasting only a matter of minutes, with sparse attendance) are included.

As Georgetown’s Matt Glassman notes, this leads to the uncomfortable scenario where a majority of House members could want to be in session, but the speaker overrules them. In fact, that’s probably the case right now: several Republican lawmakers have said they want to return to Washington, enough (when combined with all the Democrats) to form a majority.

However, as Glassman also writes, this doesn’t mean that those Republican holdouts are “hellbent” on it: they might be expressing a preference, but that’s different than a critical mass of Republicans having the political will to actually put pressure on the speaker to convene. If that were the case, it is less likely that the speaker could sustain a prolonged unilateral adjournment.

I just wanted to express my admiration and appreciation. Your articles are great: informative and well-written.

Gabe, is there any reason that all Democratic members of the House cannot return to DC and stage a sit in to call attention to Republican's inaction and to pressure them to return?