The ghosts of the federal judiciary

How judges can pick their successors.

I don’t think I need to tell any of you that, especially with a semi-functional Congress, judges play an outsized role in our modern political system, contributing to policy outcomes on immigration, abortion, the environment, and a range of other hot-button issues.

For that reason, it’s a big deal whenever a federal judge retires, since every retirement gives the sitting president one more chance to reshape the judiciary in his image. Those numbers have obvious implications for policy — but also for a president’s legacy. Commanders-in-chief jealously track how many appointments they’ve been able to make, engaging in a constant measuring contest with their predecessors. (If you’re wondering, Donald Trump added 234 judges to the federal bench in his first term. Joe Biden? He’s currently at 233, on track to surpass Trump by the end of the week.)

But because there are almost 900 judges in the federal system,1 it can be hard to stay on top of who’s coming and going. Luckily, uscourts.gov (the official website of the judiciary) comes in clutch with its “Current Judicial Vacancies” list, which keeps count of how many judges have left their seats, creating an opening for the president to fill.

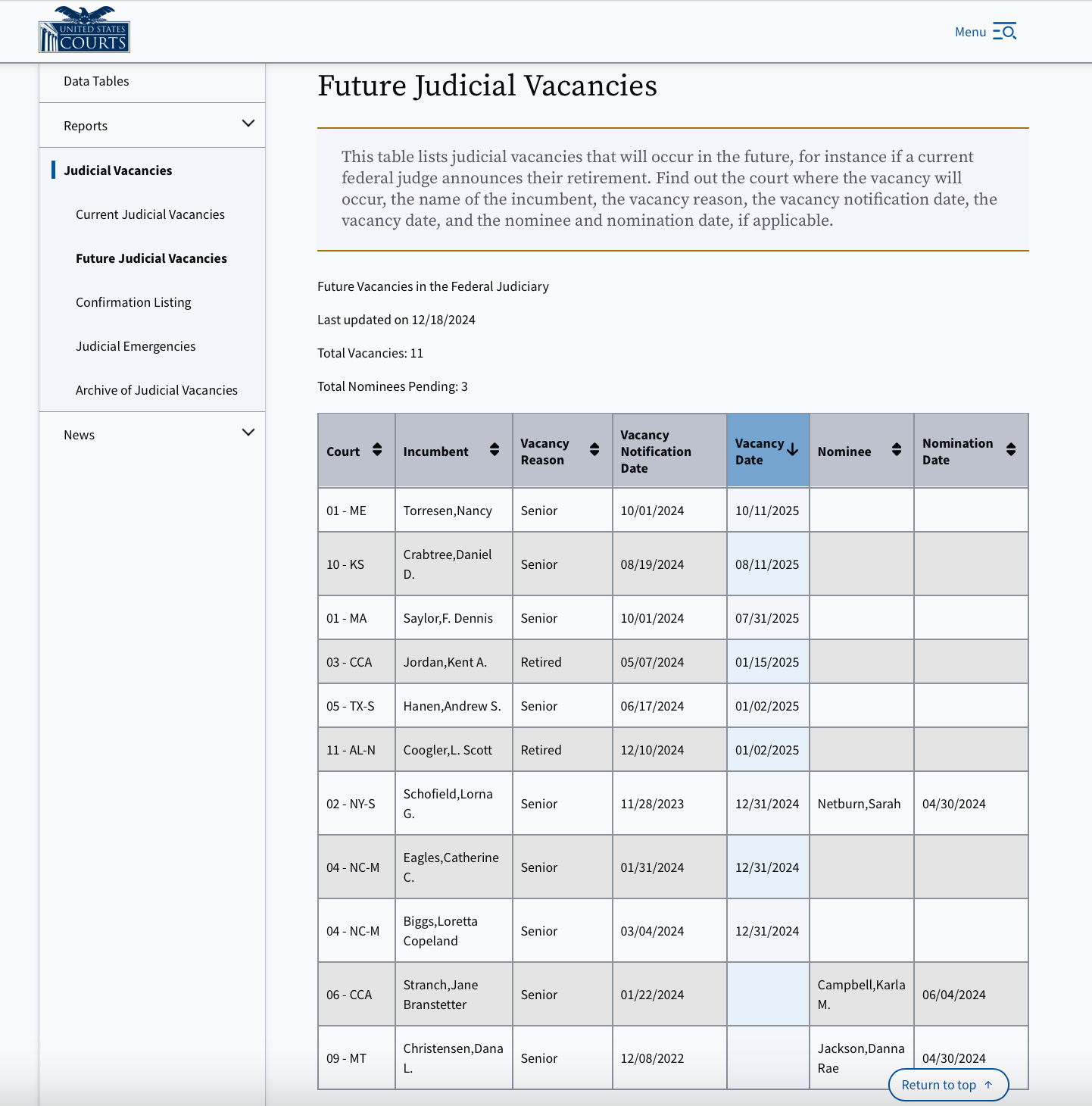

Currently, we’re at 34 vacancies—but, wait, what’s that section, “Future Judicial Vacancies” on the side?

Click over there, and you’ll find 11 more quasi-vacancies: nine judges who have announced retirement plans effective at an upcoming date, from the end of 2024 to October 2025 (Biden is theoretically allowed to replace the 2024 retirees, although he likely won’t be able to) — and then two judges at the bottom whose vacancy dates are just left blank.

What’s their deal?

Well, at this point, it probably helps to explain exactly how judicial retirements work. You see, when a judge “retires” from the federal bench, often they aren’t going far. Since 1919, judges have had the option2 to retire with “senior status,” which means the president still nominates a replacement to take their seat full-time — but the retiring judge gets to maintain an office at the court and keep making their same salary as long as their hear at least 25% of a normal caseload. (In fact, as Ed Whelan notes, senior judges end up making about $10,000 more than regular judges, because they’re privy to special tax exemptions.)3

Sounds pretty nice, right? It’s sort of like the emeritus version of being a federal judge. You get to keep making money — and also get to keep shaping federal law for years to come, as a little treat.

To give one example, there are 13 seats on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which is based in New York City. Currently, the court is made up of seven Democratic appointees and six Republican appointees. Sounds simple enough. But there are also 14 senior judges (nine Democratic appointees and five Republican appointees) who still hear some cases,4 so their leanings also need to be considered when thinking of the ideological balance of the court.

One senior Second Circuit judge, Jon O. Newman, is 92 years old. He has been on the court since 1979, and has been “retired” (with senior status) since 1997 — before I was even born! But his emeritus role allows (actually, requires) him to still hear cases; in 2019, he even participated in a high-profile case involving then-President Trump.

All this can have a subtle, but important, impact on jurisprudence. If, say, a Democratic-appointed judge were to have fully retired under Biden, they would have ensured their successor shares their same philosophy — which is nice, but ultimately keeps the ideological balance of their court the same.

But if that same judge took “senior status” under Biden, they not only got to ensure their successor agrees with them, they also get to keep hearing cases themselves — which means their court gets weighted ever so slightly towards their “side,” since there are now two Democratic-appointed judges in the mix where there otherwise would have been one.

For this reason, Professor Xiao Wang has referred to the existence of senior judges as the “Old Hand Problem,” invoking “an old hand on a ranch,” who might stick around and play a role in things for years after they might otherwise retire. (He also suggests that their effect on a court’s ideological composition is basically a form of court-packing.) Two other scholars, in a 2007 article, outright suggested that senior judges were unconstitutional.

They certainly make up a gray area in the American legal system: judges, but also not. They are the ghosts of the federal judiciary.

But let’s keep going deeper — because it gets even grayer than that.

Remember how I mentioned the two judges who are currently counted as “Future Judicial Vacancies,” who have announced plans to take senior status, but haven’t said when they’ll do it?

Generally, these judges say that their senior status will be effective “upon confirmation of a successor.” Think about how much power this gives them. Not only can they ensure which president they retire under and stay on the court themselves for decades to come — like all senior judges — but, because they haven’t set an effective date for the retirement, they can also wait around to ensure the exact person nominated to replace them is to their liking.

These judges — if they choose to exercise it — effectively have a veto power over their own replacement. If they don’t like who their successor is going to be — or if political circumstances change after they indicate plans to retire — they can just take their retirement back, since they never announced an official date when it was going to take place.

That’s exactly what happened last week.

One week ago today, the un-dated “Future Judicial Vacancies” count was at three: Jane Branstetter Stranch and Dana L. Christensen, who are on the list now, plus James Andrew Wynn, an appeals court judge who announced in January that he would take senior status (upon confirmation of his successor, of course).

But then Wynn sent President Biden this updated letter on Friday, announcing that, “after careful consideration,” he had “decided to continue in regular active service as a United States Circuit Judge for the Fourth Circuit.” His January retirement letter, he said, would be withdrawn. It was a polite way of saying, Never mind!

Wynn, kindly, apologized “for any inconvenience” he may have caused.

Hmm, what could have possibly changed between January and December 2024?

The answer, of course, is Donald Trump was elected president — meaning if Biden doesn’t fill Wynn’s seat in the next month, it will fall into Republican hands.

On top of that, we now know Biden won’t be able to fill the seat in time, under the terms of a bipartisan deal that saw Democrats withdraw four stalled appeals court nominees (including Biden’s pick to replace Wynn) in exchange for expedited confirmation of about a dozen district court picks.

Because Wynn never set a date for taking senior status, after that deal was struck, he was simply able to withdraw his “retirement.”5 An Obama-appointed judge, he clearly didn’t want to allow Trump to pick his replacement; because of the neat trick of taking senior status “upon confirmation of a successor,” he didn’t have to. It’s as clean an example as possible of a judge getting veto power over their successor.

To make things worse, isn’t even the first time this has happened since Election Day. Two other Obama-appointed judges, Max Cogburn Jr. and Algenon L. Marbley, have also quietly taken themselves off the “Future Judicial Vacancies” list in recent weeks. Both are district court judges who had previously announced plans to retire; Biden had not nominated successors for either of them.6 Fifty or so days ago, they were both fully planning to take senior status; now, they can revoke their retirements and happily wait until a Democratic president comes along to replace them.

As one would expect, Republican senators are furious — especially about the Wynn decision, since it undercuts their deal with Democrats. An ethics complaint has already been filed against him, as Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) predicted would happen on the Senate floor.

“It’s hard to conclude that this is anything other than open partisanship,” McConnell said. “They rolled the dice that a Democrat could replace them and now that he won’t, they’re changing their plans to keep a Republican from doing it.”

To be frank, I’m not quite sure how one could disagree with McConnell. Sometimes, the partisanship of judicial decisions are hazy. This one feels fairly cut-and-dried.

But I was also struck by something else McConnell said, as he warned the judges to expect ethics complaints (and requests that they recuse themselves from cases involving Trump): “If you play political games, expect political prizes.”

Here’s, in my opinion, where things get a little tricky.

Because — let’s be clear — McConnell is quite clearly right that these judges’ un-retirements smack of naked partisanship. But it’s not as if this is the opening gambit in “political games” being played with the judiciary. We crossed that bridge a long time ago — and, it should be noted, McConnell was a key figure in pushing us across.

In fact, McConnell himself played a role in a previous judge’s politically tinged decision to un-retire: that of Karen Caldwell, a George W. Bush-appointed district court judge in McConnell’s home state of Kentucky (and, as an aside, the senator’s long-ago ex-girlfriend).

In July 2022, Caldwell announced plans to take senior status (at no particular date, of course), as part of an unusual deal McConnell brokered with the Biden White House to have Biden nominate a pro-life Republican lawyer, Chad Meredith, to replace her. (The full details of the deal never became public, but officials confirmed that it involved McConnell allowing other Biden judges to receive confirmation in exchange.) But the deal fell through (ironically, because of opposition from Republican Sen. Rand Paul), and just like that, Caldwell took back her plans for senior status.

She remains a full active judge on the court today.

The whole idea of judges making their retirements tentative — “effective upon the confirmation of a successor” — opens the door for these sorts of gambits. According to Vetting Room, the tactic dates back to the second Bush administration; since then, it’s been rare for judges to rescind their retirements — but not unheard of, both for the reason Caldwell did (because they wanted a certain successor) or for the reason Wynn did (because they wanted a different president).

Note how McConnell described the precedents for the latter category on the Senate floor: “Looking to history,” he said, “only two judges have ever ‘un-retired’ after a presidential election—one Democrat in 2004, and one Republican in 2009.”

In the same speech, McConnell goes on to declare that the latest un-retirements expose “bold Democratic blue where there should only be black robes.” But just a moment before, he himself referred to a pair of judges as a “Democrat” and a “Republican,” seeming to confirm the very idea he was decrying: that the judiciary long ago became politicized.

Even putting aside un-retirements, politics has plainly been injected into the question of when judges take senior status.

As Professor Wang calculated in his “Old Hand” article, as recently as the Clinton administration, more than half of the judges who took senior status hailed from the opposite party as the president.

But under George W. Bush, more than 70% of the judges who took senior status were Republican appointees. Under Barack Obama, 57% were Democratic appointees. Under Donald Trump, it shot up to more than 80% Republican appointees. Under Joe Biden, it’s been 65% Democratic appointees. (In addition, two Republican-appointed judges have already announced plans to take senior status since the election. Decisions like that aren’t openly hypocritical like un-retiring is — but, if we’re being honest, it basically adds up to an outcome that’s just as partisan.)

Judges are (sometimes literally!) picking their successors — in some cases doubly, first by taking well-timed senior status and then by making that senior status contingent on a certain replacement.

It’s notable that this trend has increased in the 2000s, just as the judicial confirmation process was becoming increasingly politicized in the Senate. Leaders on both sides of the aisle have contributed to that, but, again McConnell is not blameless. When McConnell controlled the Senate at the tail end of Obama’s term, he not only held open a Supreme Court seat, he also allowed fewer lower court nominees to be confirmed than during any Congress since the 1950s.

Play political games, expect political prizes.

Judge Wynn himself has been a firsthand witness to this creeping politicization. In 1991, a seat on the Fourth Circuit opened up, and President George H.W. Bush chose a judge named Terrence Boyle to fill it. Democrats reused to confirm him.

Then, in 1994, another Fourth Circuit seat opened up, and President Bill Clinton nominated Wynn to fill it. As payback for Boyle, Republicans refused to confirm him.

The seat remained upon when George W. Bush entered office, and he chose — guess who — Boyle. Democrats said “no” again. Finally, in 2010, Obama came into office and re-nominated Wynn, who was confirmed. The seat stayed open for 16 years, because of obstructions by Democrats and Republicans. It was like an “old family feud,” the Los Angeles Times reported: the Hatfields v. McCoys, but make it the Wynns vs. the Boyles.

Because of Wynn’s decision last week, the sordid, partisan history of his Fourth Circuit seat will continue.

And there you have it: a fragile system — which increasingly shapes Americans’ daily lives — built on quasi-retirements, ghostly judges, partisan take-backs, and a dysfunctional Senate.

It’s no small wonder that a Gallup poll released this week found that the segment of Americans with confidence in the nation’s judicial system has dropped seven points in the last year — and 24 points in the last four years — reaching a record low of 35%.

And about to be 10 more, thanks to a bipartisan bill! (No, not this bill.)

To be clear, not all judges have the option — at least not immediately. Eligibility is determined by the “Rule of 80”: once the judge has reached age 65, if their age and years of service on the bench add to a sum of at least 80, they’re able to “go senior.”

In case you’re wondering, Supreme Court justices can also take senior status, which normally involves them sitting in on lower courts during their retirement. Stephen Breyer, for example, has done this in the First Circuit. Because this option exists, some have proposed that Supreme Court justices be required to take senior status after 18 years of service — a backdoor way to impose term limits without violating the constitutional requirement that justices serve lifetime tenures. It’s unclear if this would be legal; ultimately, it would be up to — who else — the Supreme Court.

Strangely, usourts.gov says that senior judges “essentially provide volunteer service to the courts,” which is misleading at best. To be clear, they do play an important role pitching in to address the judicial backlog crisis — especially since President Biden is poised to veto a bill creating new judgeships — but they are very much paid handsomely for it.

In total, senior judges handle about 20% of the total district and appellate caseload, per uscourts.gov. On the district court level, they can preside over a trial like any other judge. On the appellate court level, they can participate in the three-judge panels that decide most circuit court cases. They cannot participate in en banc decisions of the full appeals court. (Professor Xiao Wang also notes that they often opt to take part in certain types of cases but not others, giving them disproportionate sway over some areas — which means this little-known group not only get unusual say over their successors, but also over the cases they are given.)

Note that the nominee to succeed the aforementioned Judge Stranch was also withdrawn as part of this deal — since Stranch also didn’t set an effective date for her retirement, she is the next judge to watch for a potential “un-retirement.”

Hmm…seems like a cushy deal to me. Retiring with “senior status” at full pay with a requirement of weighing in on at least 25% of cases is better than being on the Supreme Court, IMO. Maybe that retirement pay should be cut by 75%!

“McConnell is not blameless.”

For me, that’s the operative and understated sentence in this interesting piece! McConnell has been the generator of distrust in judicial nominations for years now—undermining the system.