More Humpty Dumpty Cases: Trump and the National Guard

How a long-forgotten Rhode Island civil war plays into the president’s deployments.

Last week, President Trump gathered America’s top military brass and told them that the U.S. is facing an “invasion from within.”

“We should use some of these dangerous cities as training grounds for our military,” the president said.

This week, he has tried to turn that idea into a reality. Having already deployed the National Guard to Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles this summer, he has moved in recent days to deploy additional units to Portland and Chicago.

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last night that, for now, the Oregon National Guard can remain under federal control but cannot deploy to Portland. Meanwhile, around 500 troops from the Texas and Illinois National Guards arrived in Chicago yesterday after a district judge declined to block their deployment. Both the 9th Circuit and the Illinois district judge will hear oral arguments today on what the longer-term, though still temporary, postures in those cases should be.

This flurry of litigation reflects the awkward middle ground that the National Guard occupies in our constitutional system. “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States,” Article II tells us, “and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.”

Thus, the U.S. Armed Forces were created — but, true to our federalist system, so were a network of smaller militias, which would be commanded by the separate states. Except, that is, when they wouldn’t be.

Having just fought a Revolutionary War that relied in part on state militias, and with many Americans feeling as much loyalty to their states as to their country, the Founders just weren’t ready to give up on the idea of a military force rooted in local governance. They didn’t think it was odd to have 13 mini-militaries spread throughout the states; if anything, what made some of them uncomfortable was the notion that these militias (which we now know as the National Guard) would be ultimately accountable to a central power.

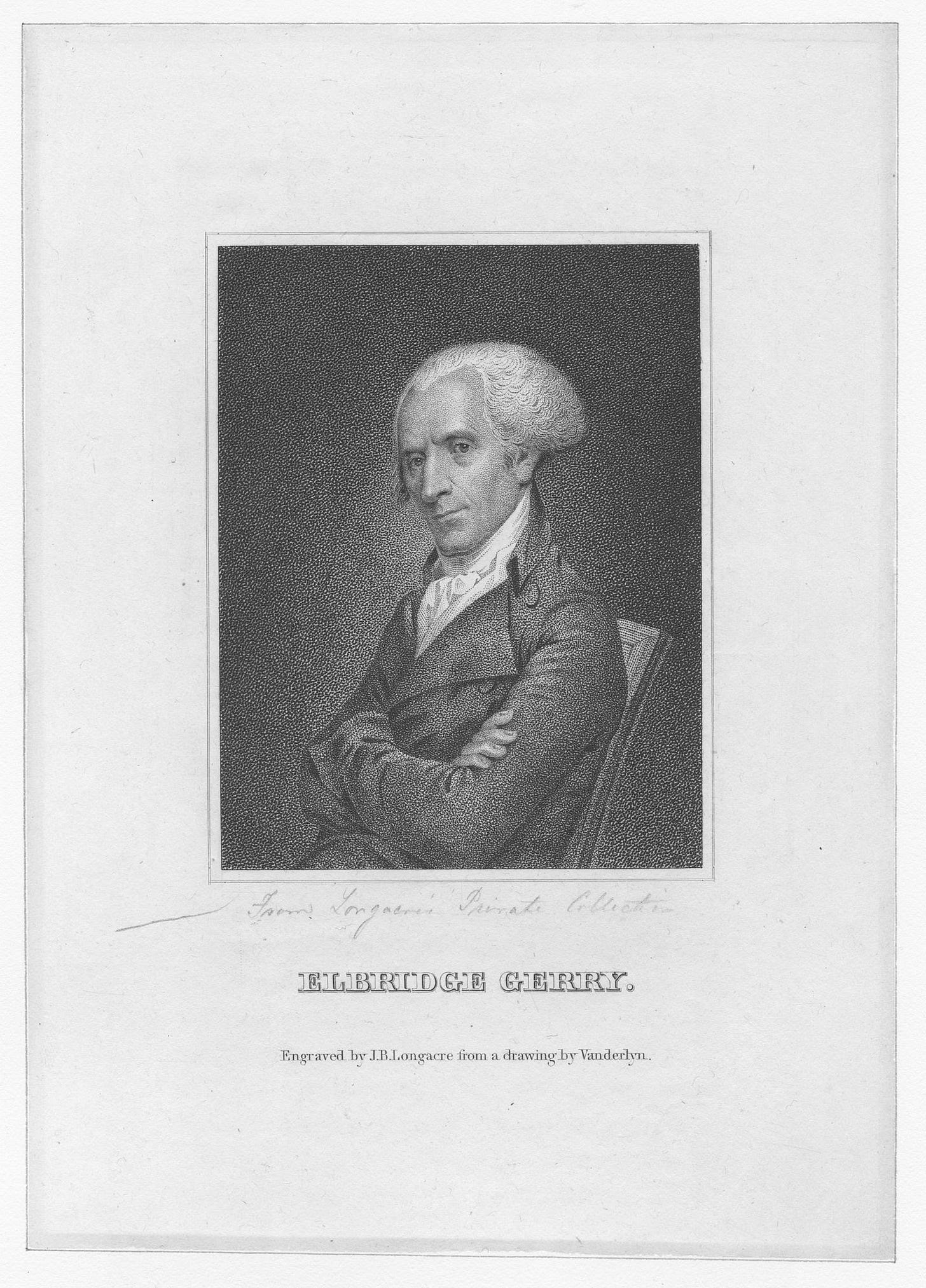

At the Constitutional Convention, Massachusetts delegate Elbridge Gerry (he of “gerrymandering” fame) said that he would rather “let the citizens of Massachusetts be disarmed” entirely than “take the command [of the militias away] from the states and subject them to the [national] legislature.” A system that didn’t allow for pure state control over their militias would be considered “despotism,” Gerry warned.

Gerry’s concerns notwithstanding, the federalist militia system was created. Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions,” allowing legislators to set the terms of when the militias could be nationalized.

Congress quickly delegated this power to the president, first with the Militia Act of 1792, then the Militia Act of 1795, and finally the Militia Act of 1903, which created the National Guard system as we know it.

In its modern iteration, each state maintains a National Guard unit, whose members are usually part-time (coming in one weekend a month for drills and two weeks a year for training) unless they are called into active service. There are three ways for the units to be activated:

1. A state governor can deploy their National Guard unit. Gov. Tim Walz (D-MN) deployed his unit in July, for example, after St. Paul was hit with a cyberattack. Gov. Greg Abbott (R-TX) deployed his unit in June to help law enforcement manage a “No Kings” protest. Since Washington, D.C., doesn’t have a governor, its National Guard unit is commanded by the president, so Trump’s deployment of the D.C. National Guard effectively falls under this category.

2. A National Guard unit can be deployed by the president at the governor’s request. The unit then remains under the governor’s control but their service is paid for by federal funds. The relevant legal authority here is Title 32 of the U.S. Code. This is how the Tennessee National Guard is being deployed to Memphis, at the request of Gov. Bill Lee (R-TN).

3. The president can “federalize” a National Guard unit, which means it is deployed fully under his control, not the governor’s. This can happen with the governor’s consent, like in 1968 when President Lyndon Johnson deployed National Guard units to quell protests after MLK’s assassination. Or it can happen without a governor’s approval, as when President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard to allow the “Little Rock Nine” to attend school in 1957.

This authority comes from Title 10 of the U.S. Code. That title includes the codification of the Insurrection Act, which allows the president to federalize the National Guard whenever he “considers that unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any State by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.”

That law, originally approved in 1807, has been invoked 30 times throughout history, most recently by President George H.W. Bush in response to the Los Angeles protests after the beating of Rodney King in 1992. Trump is considering invoking it, but has not yet done so.

Instead, the statute Trump is using in Chicago and Portland is 10 U.S. Code § 12406, which states:

Whenever—

(1) the United States, or any of the Commonwealths or possessions, is invaded or is in danger of invasion by a foreign nation;

(2) there is a rebellion or danger of a rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States; or

(3) the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States;

the President may call into Federal service members and units of the National Guard of any State in such numbers as he considers necessary to repel the invasion, suppress the rebellion, or execute those laws. Orders for these purposes shall be issued through the governors of the States or, in the case of the District of Columbia, through the commanding general of the National Guard of the District of Columbia.

Trump has said that protests at ICE facilities in both cities have prevented the government from being able to “execute the laws of the United States,” thus requiring the National Guard to be deployed to protect the facilities.

Importantly, under the Posse Comitatus Act of 1874, federal military personnel are generally not allowed to take part in domestic law enforcement. This law does not apply to the National Guard when they are activated by a state governor or activated under Title 32 (when the governor still commands them). It also does not apply to activations under the Insurrection Act, but it does apply to the type of Title 10 activations that Trump is currently attempting.

In June, after Trump deployed National Guard troops to Los Angeles under the Title 10 rationale, U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer (brother of another famous jurist) ruled that a president’s invocation of 10 U.S. Code § 12406 can be reviewed by the courts — in the legal parlance, it is “justiciable” — and that “none of the three statutory conditions for invoking that statute were met.” (The Trump administration has argued that the matter is not reviewable at all.)

“The statute permits the President to federalize the National Guard “‘[w]henever’ one of the three enumerated conditions are met, not whenever he determines that one of them is met,” Breyer wrote. The judge analyzed the dictionary definitions of each of the three conditions, and ruled that they had not been satisfied.

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with Breyer that the question was reviewable, but said that the review “must be highly deferential.” According Trump that deference — and noting evidence that protesters had thrown Molotov cocktails, concrete chunks, and bottles of liquid at ICE agents — the appeals court ruled that Trump had satisfied the needed conditions.

In Portland, U.S. District Judge Karin Immergut similarly considered the evidence — noting that the Trump administration had pointed to “only four incidents of protesters clashing with federal officers in the month of September preceding the federalization order” — and ruled that “the protests were small and uneventful,” and did not prevent the government from enforcing the laws.

“In sum, the President is certainly entitled ‘a great level of deference,’ in his determination that he is ‘is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States,’” Immergut continued. “But ‘a great level of deference’ is not equivalent to ignoring the facts on the ground.” Trump’s determination “was simply untethered to the facts,” she wrote.

That decision by Immergut, a Trump appointee from his first term1, was labeled a “legal insurrection” by White House senior adviser Stephen Miller. The 9th Circuit will hear oral arguments today to decide whether to keep her ruling in place.

In essence, what we have here is another string of Humpty Dumpty Cases.

That’s my name for cases that turn on whether the president has the same powers Humpty Dumpty claimed in Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking-Glass” book: “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

When the president says that a foreign government has launched an “invasion or predatory incursion” under the Alien Enemies Act, does that make it so? When a president imposes tariffs by saying that the trade deficit poses an “extraordinary and unusual” threat, can that be second-guessed? If the president says “cause” exists to fire a Fed governor, does that mean that cause exists?

And, here: if the president says that he is “unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States,” can he deploy the National Guard? Or is a judge able to examine that determination?

Of course, the answer won’t be the same for each of these statutes. Each of them come with their own wording, their own case law and precedents.

I went in search of the Supreme Court precedents that judges will be looking toward in the National Guard cases, that might tell us how justiciable Trump’s deployments will be. It turns out, they aren’t easy to find: it’s been a long time since the court has wrestled with these questions.

In fact, to examine one of the key precedents, we have to venture all the way back to one of the stranger episodes in American history: that time in the 1840s when there were two rival governments fighting for control of Rhode Island.

At the time, Rhode Island was the only U.S. state that hadn’t adopted a new constitution since the country was founded: it was still using its Royal Charter from when it was a colony. The document — written in 1663 — included a land-owning requirement to vote, which was no longer the norm almost two centuries later.

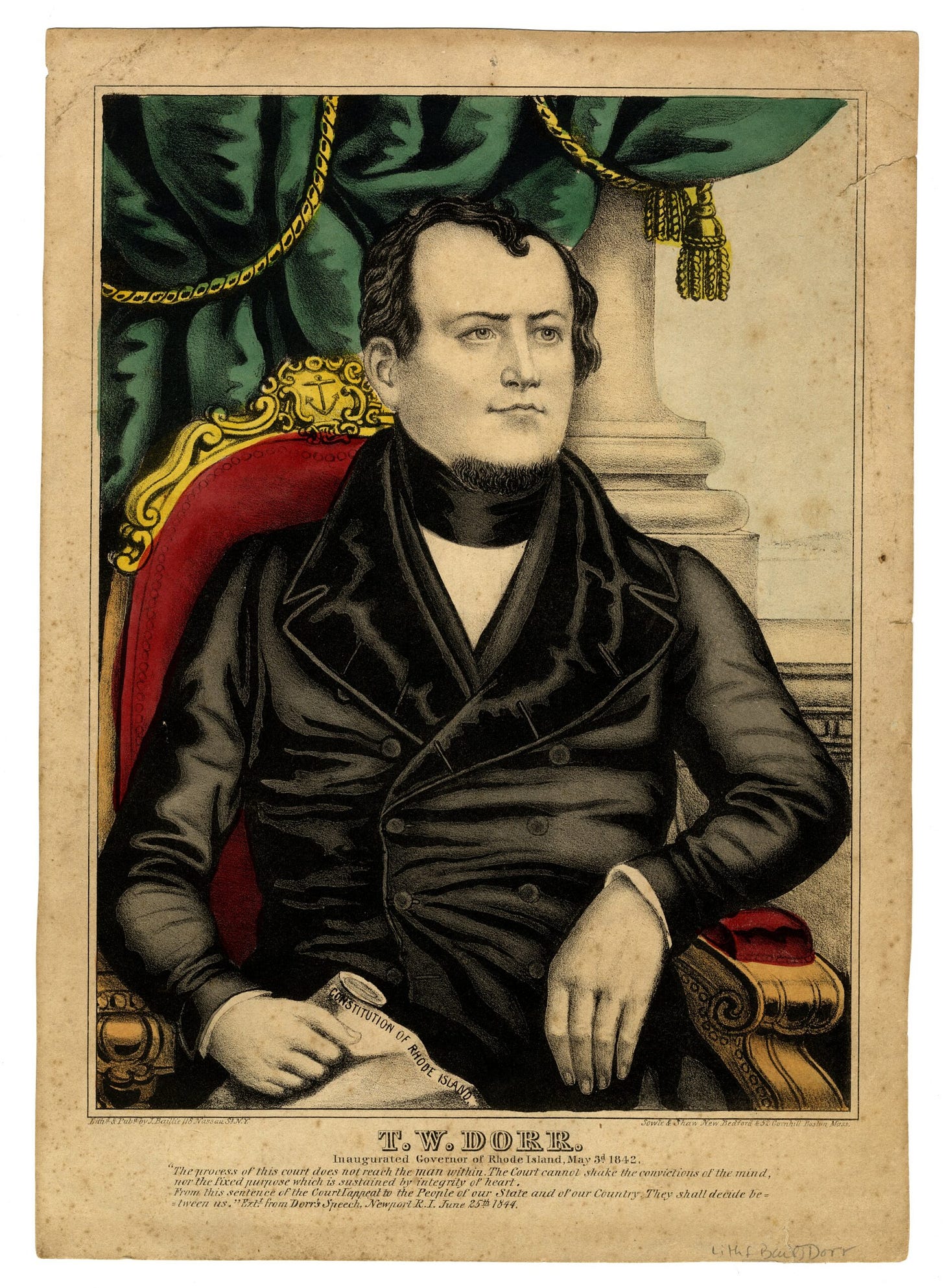

A group of Rhode Islanders who called themselves the “Dorrites” — after their leader, Thomas Wilson Dorr — decided to write a new constitution with expanded voting rights. Under the terms of their constitution, they held a new election and chose Dorr as the new governor. Meanwhile, a competing faction known as the “Charterites” swore fealty to the existing colonial charter and the existing governor, Samuel Ward King.

The Dorrites set up a government in Newport. The Charterites continued to rule from Providence. Fighting quickly broke out between the two, creating a miniature civil war in Rhode Island known as “Dorr’s Rebellion.” (To make a long story short, Dorr was eventually defeated, although Rhode Island did approve a new constitution before long.)

Cool story, but what does it have to do with the National Guard? During the uprising, Governor King repeatedly petitioned then-President John Tyler to deploy the National Guard to quell the rebellion. Tyler declined, but when a case connected to the episode eventually reached the Supreme Court in 1849 — Luther v. Borden effectively asked the court to recognize the Dorrites as the lawful government of Rhode Island, under the theory that Article IV of the Constitution guarantees each state a “Republican Form of Government” — the court addressed the question of whether Tyler would have been able to intervene.

“After the President has acted and called out the militia, is a Circuit Court of the United States authorized to inquire whether his decision was right?” Chief Justice Roger Taney asked in his majority opinion.

No, he answered. “If the judicial power extends so far, the guarantee contained in the Constitution of the United States is a guarantee of anarchy, and not of order,” Taney wrote.

The chief justice continued:

It is said that this power in the President is dangerous to liberty, and may be abused. All power may be abused if placed in unworthy hands. But it would be difficult, we think, to point out any other hands in which this power would be more safe, and at the same time equally effectual.

When citizens of the same State are in arms against each other, and the constituted authorities unable to execute the laws, the interposition of the United States must be prompt or it is of little value. The ordinary course of proceedings in courts of justice would be utterly unfit for the crisis. And the elevated office of the President, chosen as he is by the people of the United States, and the high responsibility he could not fail to feel when acting in a case of so much moment, appear to furnish as strong safeguards against a wilful abuse of power as human prudence and foresight could well provide. At all events, it is conferred upon him by the Constitution and laws of the United States, and must therefore be respected and enforced in its judicial tribunals.

Taney cited an even earlier case, Martin v. Mott, which also serves as an important precedent here. Like in Luther v. Borden, the Supreme Court ruled in that 1827 case that that the president’s deployment of the “militia” — what we now know as the National Guard — was up to him.

“Whenever a statute gives a discretionary power to any person to be exercised by him upon his own opinion of certain facts, it is a sound rule of construction that the statute constitutes him the sole and exclusive judge of the existence of those facts,” Justice Joseph Story wrote for a unanimous court.2

In other words: the Supreme Court — at least two centuries ago — felt the president does have Humpty Dumpty Powers when it comes to deploying state militias.

The Trump administration has cited Martin and Luther (the cases, not the Protestant reformer) in briefs surrounding its recent National Guard deployments. Judge Breyer felt that Martin, which was the basis of Luther, didn’t apply here because it had to do with deployment in wartime (during the War of 1812); all parties agree that deference to the president is higher in matters of war.

The 9th Circuit, overturning Breyer, disagreed, finding that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Luther (since it was about an internal dispute) showed that the court believed Martin applied to matters both foreign and domestic. In the Los Angeles case, the state of California protested that Martin was almost 200 years old, and that understandings of the relationship between the executive and judicial branches had progressed since then.

“But Martin’s continuing viability is not for us to decide,” the 9th Circuit ruled. “The Supreme Court has admonished that ‘[i]f a precedent of this Court has direct application in a case, yet appears to rest on reasons rejected in some other line of decisions, the Court of Appeals should follow the case which directly controls, leaving to this Court the prerogative of overruling its own decisions.’”

Martin v. Mott was an early example of the Supreme Court’s Political Questions Doctrine: times when it says, “Yeah, interesting case you got there. We don’t want anything to do with it.” These are questions that the court says must be decided by the “political branches,” the White House and Congress.

Is the government of Rhode Island “republican” in nature, or should a new government be set up in its place? Yeah, we’ll pass on that one. The president wants to deploy the National Guard? That’s up to Congress to set the limits, and the president to carry them out.

But the Political Questions Doctrine has ebbed and flowed through the years: it does remain especially strong in cases surrounding the military and foreign affairs… but what about a case on the military in a domestic context? There’s much less of a modern record built up for such cases, which means judges across the country could soon be leafing through histories of Dorr’s Rebellion to suss out the answer here.

In other news…

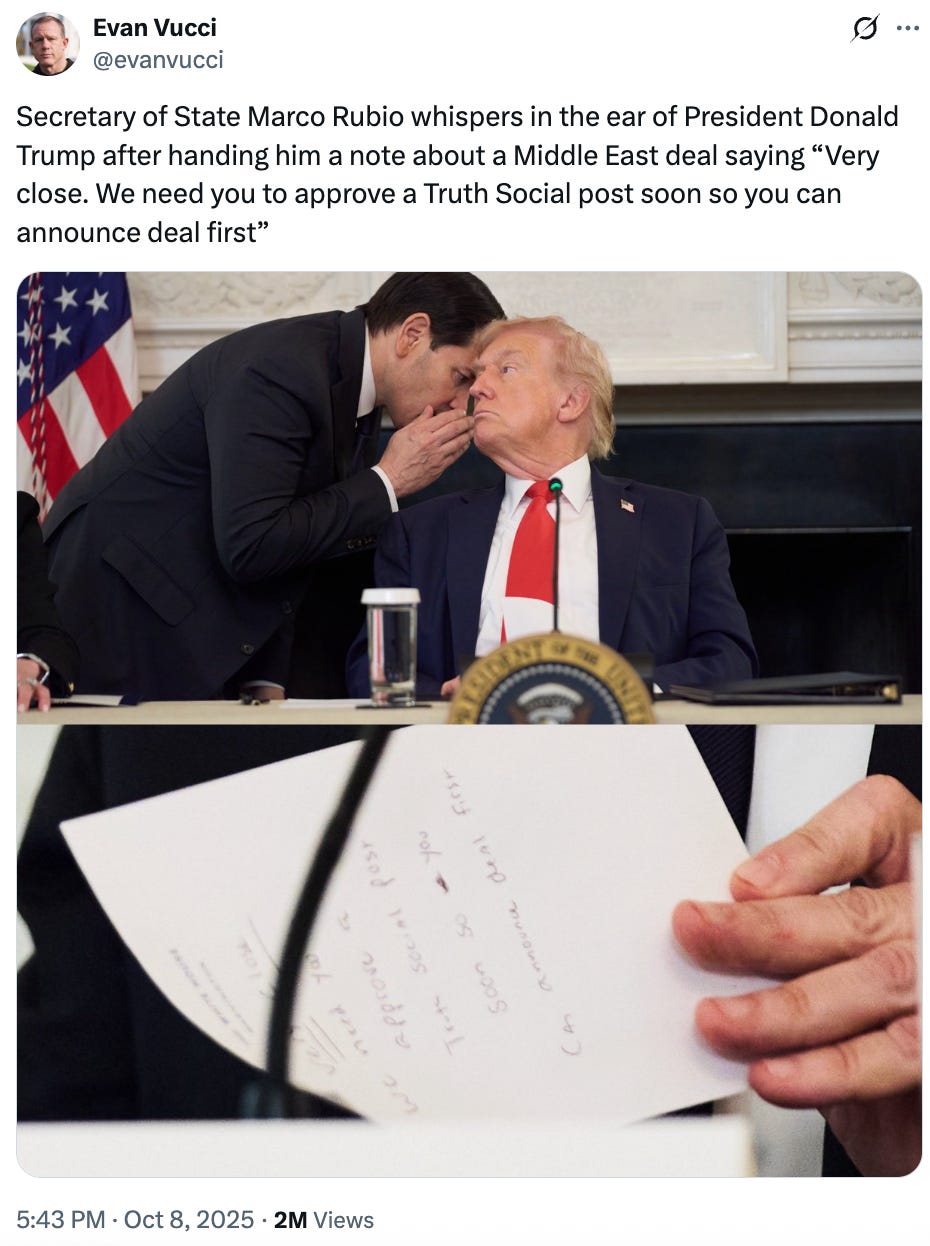

Israel and Hamas have agreed to a ceasefire deal that will free all of the living Israeli hostages in exchange for Palestinian prisoners, likely bringing an end to a two-year-long war. The agreement, based on the first phase of a proposal by President Trump, marks a major diplomatic achievement for the Trump administration.

Democrats say even missed paychecks for US troops won’t be enough to end shutdown alone (CNN)

Senate votes down war powers resolution aimed at blocking Trump’s strikes on alleged drug boats (CBS)

Inside the Justice Department Where the President Calls the Shots (WSJ)

That said, Immergut is a Trump appointee in a blue state — so, if you recall my August piece on “blue slips,” your alarm bells should be ringing. Indeed, Immergut was chosen by President Trump from a list provided by Democratic Sens. Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley of Oregon, after applying to their judicial selection committee. She’s had a varied background: having been registered as a Democrat, Independent, and Republican; worked on Ken Starr’s investigation of Bill Clinton; appointed as a U.S. attorney by George W. Bush and as a state judge by a Democratic governor.

Immergut has been described by local media as a “moderate, pro-choice Republican” who is “widely admired in the legal community” in Oregon. As I wrote in August, blue slips (which allow senators to have a say in the district court judges selected from their state, even when the judge is being nominated by a president of the other party) promote judges with respected legal credentials and moderate, politically heterodox backgrounds.

Story was analyzing the Militia Act of 1795, which is no longer in effect, but it’s the predecessor statute to the Militia Act of 1903, the modern National Guard law. Judges generally look at rulings on predecessor statutes with similar language (as is the case here) as relevant to their legal decisions.

Interestingly, as Steve Vladeck notes, the Militia Act of 1792 — the predecessor statute to the 1795 law — explicitly included a role for judges to review the facts of presidential militia deployments. But that language was scrapped in the 1795 and 1903 versions.

I suppose they don’t get that trump is the invasion from within.

The Trump Administration has changed its rationale for using the National Guard from fighting crime in so-called crime-ridden cities to one of protecting ICE facilities and personnel. Such protection, if it is actually needed, would only be because of the thuggish behavior of ICE itself. So the Trump Administration has in fact created the conditions it seeks to protect ICE from.