Kamala Harris has done something impressive

A graph that calls for some humility.

Kamala Harris may win this election; she may not. It’s a flat-out tossup and neither I nor anyone else can tell you the outcome in advance.

But, no matter what happens, she pulled off something yesterday that is genuinely impressive: turned around a 17-point polling deficit in about two months.

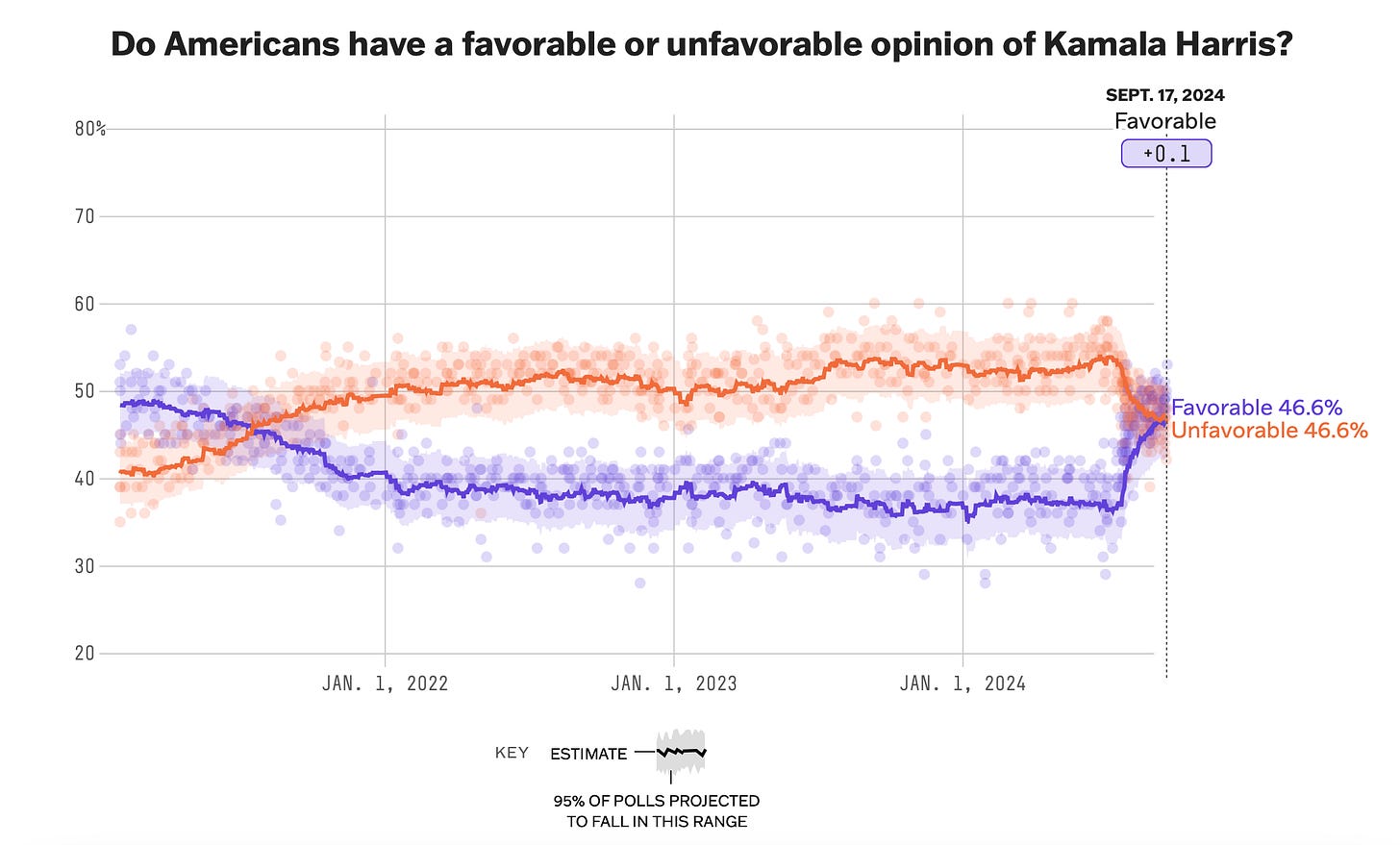

According to the FiveThirtyEight polling average, in early July — shortly after the presidential debate that would end Joe Biden’s career — around 54% of Americans were telling pollsters that they had an unfavorable opinion about Kamala Harris. Only around 37% were telling saying they had a favorable opinion of her.

Flash forward to yesterday, and the outlet’s average showed more Americans expressing a favorable than unfavorable opinion of the once-unpopular vice president. Harris’ favorability rating had shot up around nine points, while her unfavorability rating dropped around eight points in tandem — landing her above water for the first time since July 2021.

And, in case you’re the type of person who likes to average your polling averages (in which case, you’re my type of person) — here’s the graph from RealClearPolitics, which shows the same thing. (In fact, RCP had opinions on Harris turning net-positive last week.)

Especially in our polarized media climate, it’s incredibly unusual to see a favorability graph with a sharp upward spike like that — a politician gaining that much popularity in such a short amount of time.

Yes, it has happened before in presidential politics, but it’s been a while. Below is a 2016 graph from pollster Charles Franklin, charting the net favorability of every presidential nominee since 1976. As you can see, two candidates have had similarly sharp increases in net favorability: Michael Dukakis in 1988 and Bill Clinton in 1992, with both increases (like Harris’) taking place around the time they captured their party’s nominations.

But, since the late 90’s, we’ve settled into a pretty familiar era of flat lines — of Americans adopting their opinions about a candidate at the beginning of a cycle, and barely changing their minds as time went on. Donald Trump is the archetypal example of that, as someone whose favorability rating has barely moved in years. Occasionally, you’ll still see people whose unfavorability numbers will shoot up in a short amount of time (Sarah Palin and JD Vance are both examples of that; so is Biden after the Afghanistan withdrawal) — but, at a time when politics are incredibly polarized, someone becoming popular almost overnight is much less common.

I think the sudden turnaround in Harris’ polling offers a few important lessons about American politics.

First off, it’s a call for humility.

If you had polled 100 political reporters, pundits, and strategists at the beginning of the summer and asked them if this was going to happen — if Kamala Harris, who underperformed as a presidential candidate in 2020, who had struggled to find her footing as vice president, who had been the least popular veep in recent history, was going to suddenly become well-liked by the autumnal equinox, my guess is approximately none of them would have answered “yes.”1

That means this is a valuable reminder for people who follow politics for a living that not everything is predictable. Sometimes circumstances change — in a huge way — and it leads to public opinion shifts that we just can’t see coming. Sometimes people we had counted out rise to the occasion (and sometimes people we expect to soar end up crashing and burning2). It’s always important to take the long view, to not get too stuck in your thinking that you don’t keep in mind the possibility of a change that’s about to happen.

At the same time, I also think Harris’ sudden rise in popularity tells us that, sometimes, politics isn’t as complicated as we make it out to be.

It might have been reasonable, after Harris became a presidential candidate, to hypothesize that opinions on her would become even more polarized. We’ve seen that happen before: a great example is Hillary Clinton, who was quite popular in the somewhat apolitical roles of First Lady and Secretary of State and much less popular as a presidential candidate in 2008 and 2016.

However, if political experts had taken seriously what voters had been telling pollsters for months, it might have been clear that Harris would have a different trajectory.

If there was one clear theme in polling of this election before the first debate, it was that Americans really didn’t want to have to choose between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. Many journalists, myself included, dismissed the possibility of dislodging either of them from their respective tickets — how would the mechanics of such an ouster work, and would it really change the contours of the race? — but, as it turned out, all it took for a candidate to become popular in this election was exactly what voters said it would: for them to be Not Biden and Not Trump.

Put this way, the sharp upward line on Harris’ polling graph begins to look like a numerical representation of the sigh of relief many undecided voters — the so-called “double haters” — let out when a fresh face finally joined the contest.

Nikki Haley said back in January that “the first party to retire its 80-year-old candidate is going to be the one who wins this election.” We don’t yet know if that’s true, but Harris’ polling turnaround at least tells us there was something there: Americans’ distaste for their two options was real and the two parties were unwise to ignore it for so long. There was no need to complicate what was right in front of our faces the whole time.

As a corollary to that point, the change in Harris’ favorability also tells us our system of primary elections might be ripe for fixing. If Democratic Party elites were able to do in a matter of days what Democratic Party voters struggled to accomplish — give the party a candidate able to actually mount a credible campaign — perhaps smoke-filled backrooms are preferable modes to selecting presidential nominees than primary elections.

I’m not saying we should revert completely to the days of party bosses picking nominees, but maybe it would be better for parties in the long-run if party leaders got some sort of a thumb on the scale. (Make superdelegates great again?) For evidence, just look at the popularity of the standard-bearer that Democratic voters put forward this year (almost 15 points underwater), compared to the candidate that Democratic leaders essentially selected (now more popular than she is unpopular, however barely).

My guess is few changes to the primary system will emerge as a result, but it’s hard to look at how Biden was doing vs. how Harris is doing and deny that — at least this cycle — the primary voters got it wrong and the leaders got it right, in terms of what was best for the party. (And in terms of what represented the desires of less engaged, non-primary-voting voters. Again, no need to complicate this: just listen to what less engaged voters were screaming out for all cycle!). The backroom method is certainly less democratic, but it is also much more efficient and, possibly, effective.

One final point: the Harris shift should also change how we talk about vice presidents. Take a look at Joe Biden’s polling trajectory, via FiveThirtyEight:

Do you notice how it looks almost the same as Harris’ — until it doesn’t? Yes, Harris was the least popular vice president in modern history…but that was largely because Biden is the least popular president in modern history. As his vice president, Harris’ favorability rating plummeted in tandem with Biden’s, starting after the Afghanistan pullout; then, as soon as Harris poked out of his shadow, her favorability rating recovered and began to move of its own accord.

Political scientist Jody Baumgartner wrote in 2017 that, “in the aggregate, citizens seem to have no independent opinion of vice presidents” — so we should stop pretending like they do. By and large, voters’ opinions of vice presidents are just their opinions of the president; until the VP mounts a campaign for themselves, it’s impossible to know how the public will react to them, a lesson many forget in how they covered Harris and which shouldn’t be forgotten again.

Now, I know what you really want to hear: Does the turnaround in favorability tell us anything about how the election will end up?

It’s hard to say.

FiveThirtyEight has studied this before, and the presidential candidate with a higher net favorability usually wins in November. But there have been exceptions, and the most recent one is Donald Trump himself. (Another is the aforementioned Dukakis.) So if there is anyone we know can win an election despite being deeply disliked by voters, it’s Trump.

Nevertheless, Harris’ favorability can tell us some things about the state of the race. First off, it’s worth noting that Harris moving above-ground in favorability has happened around the same time as a positive stretch for her in the topline polls, including a high-quality poll showing her with an edge in critical Pennsylvania and a poll with good news for her from the well-respected pollster Ann Selzer.

It also tells us that — in addition to Harris benefiting from being Not Trump and Not Biden — she has benefited from a well-orchestrated rollout that successfully united the Democratic coalition behind her.

In line with findings that very few voters express favorable opinions of the other party’s nominee,3 Harris’ favorability rating has not improved among Republicans since July. Instead, her uptick can be attributed to much higher numbers among Independents and key Democratic-leaning groups — specifically Black, Hispanic, and young voters — who have low opinions of Biden and had low opinions of her when her role in the 2024 race was as his running mate.

A key question is whether she can maintain those heady numbers through November.

One way she has achieved them, after all, is by remaining largely vague on policy. This was on display just yesterday, in her interview with a panel of Black journalists in Philadelphia. As NBC reports:

Reporters Tonya Mosley of NPR, Gerren Keith Gaynor of TheGrio and Eugene Daniels of Politico repeatedly pressed Harris for direct answers on other topics, interrupting her multiple times when she veered away from the subject or rambled. She dodged a potentially contentious moment when Mosley stopped her during an answer about gun control by laughing through the moment.

The audience of about 150, including 100 college students, began to signal discomfort when Harris avoided answering a question about whether she would issue an executive order to create a commission to study reparations. Ultimately, she said, it would come down to Congress, an answer that seemed to deflate some of the attendees.

Some members of the audience also signaled displeasure when she gave an indirect answer about whether she would continue the Biden administration’s approach to the Israel-Hamas war.

In addition to being born more recently than the 1940s, dodging thorny questions — “laughing through the moment” — has helped Harris remain untethered to controversial policy positions, allowing her favorability rating to rise. But the strategy also comes with risks. Harris is betting that she can keep everyone happy through November — but if clashing parts of the coalition grow antsy before then, and grow tired of hearing non-answers, she may have a problem on her hands.

I’ve been enjoying the New York Times’ focus groups this cycle, and I was struck by their most recent edition, with undecided young voters. In line with polling, many of the voters said their opinions of Harris had improved in the last month, while — strikingly — only one said the same about Trump, a reminder of how few favors he has done himself this summer.

But when asked to name one word to describe Harris, nearly all of the undecided voters gave answers that show the pitfalls of a politician walking on tiptoes to please everybody: “Fake.” “Rehearsed.” “Flip-flopper.” “Actress.” “An empty suit.” “Insincere and shallow.” “Vibes candidate.” “Politician.” “Political P.R.”

If that is at all representative of how independent voters — even ones whose opinions of Harris are improving — feel towards her, Harris needs to make some tough decisions.

High favorability can be a political gift — but it can also be a mark of a candidate declining to take firm positions for fear of losing votes, which can become a vulnerability in itself if voters eventually catch on. Live by vagueness, die by vagueness. Harris is currently coasting off non-answers and the high favorability that comes with them — but they could also be her undoing if she isn’t careful.

In fact, more of them probably would have told you that Biden should swap out Harris for another VP than those who would have said that the party should swap out Biden for Harris.

Ironically, Harris c. 2019 is an example of the latter

It used to be common for a presidential nominee to at least receive a favorability rating in the 20s or 30s from the opposite party. (Dukakis even received a 50% favorability rating from Republicans in 1988!) Now, it’s rare for a candidate to have anything higher than single-digits favorability from the other party.

While I agree with a lot of your analysis here, I can't quite get on board with the idea that "the primary voters got it wrong and the leaders got it right." The primary voters faced the constraint of who was actually running ... which was definitely influenced by the party leaders. And the party leaders that rallied to oust Biden this summer weren't acting in a vacuum; they were responding to voters. So I agree that party leaders do need to get their back-room shit together, but NOT because they're smarter or better positioned to make good decisions. Rather, they should take a dose of that same humility you're talking about, take into account that their ability to predict voters is imperfect, and recognize that the will of the electorate goes beyond who is "up next" according to some internal logic of the party.

Good analysis of Harris’ possible vulnerabilities by continuing to be vague on key issues. What about Trump? He has been less than vague, giving contradictory answers on virtually everything!