I was inside the Supreme Court yesterday. It got tense.

The court’s facade of unity is cracking, one sarcastic jab at a time.

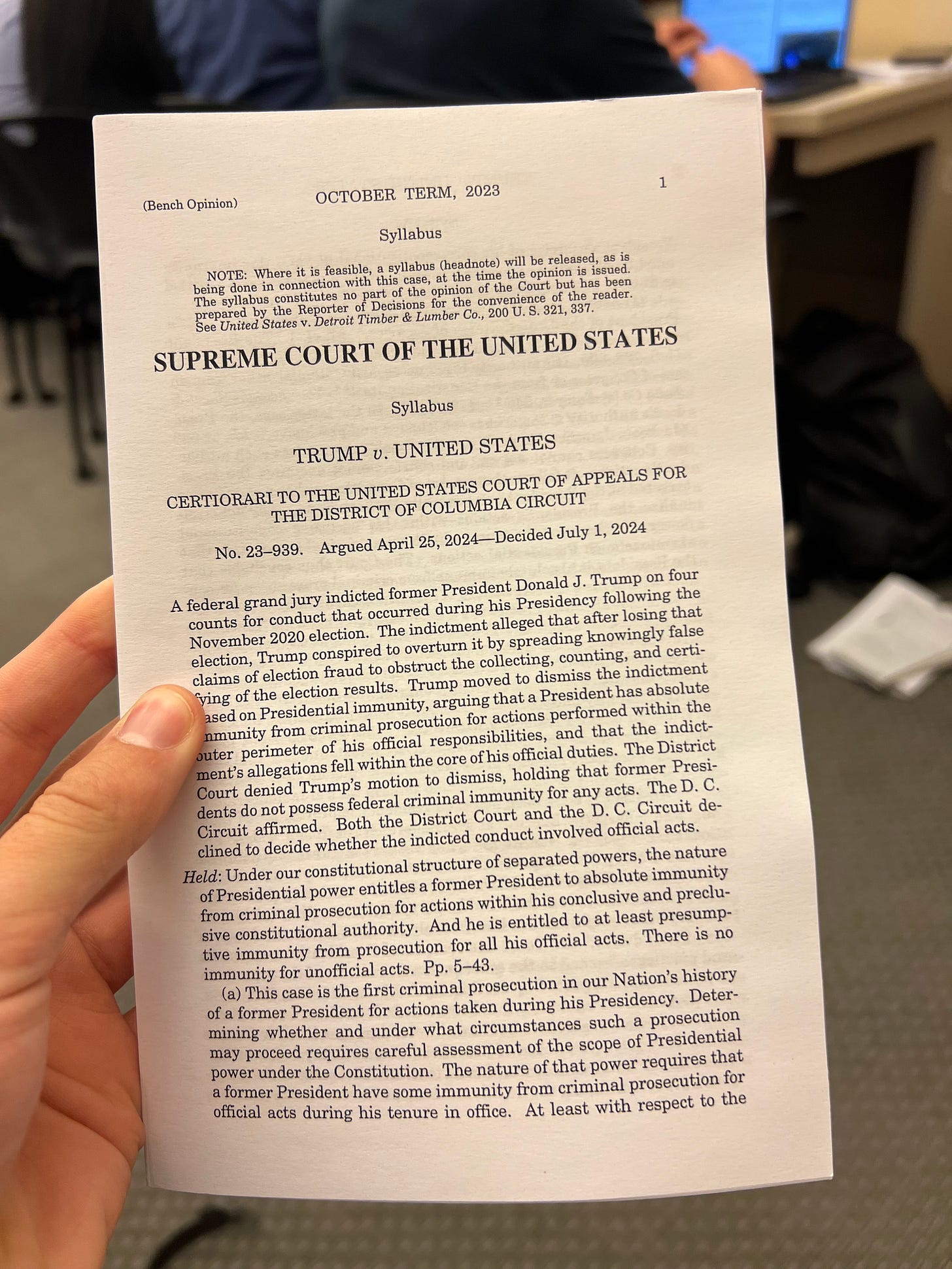

I was one of 19 reporters sitting inside the Supreme Court on Monday as the justices announced a 6-3 opinion, in response to Donald Trump’s January 6th indictment, finding that some presidential actions are absolutely immune from prosecution while others are not.

Journalists are not allowed to bring electronic devices into the courtroom. The account below stems from my written notes taken during the proceedings. While the justices read summaries of their opinions (and, sometimes, their dissents), they often diverge from their own written word, offering glimpses into their thinking available only to those inside the courtroom. I was there, however, which means I can now share what I gleaned with you:

Outside the Supreme Court, the institution faces something of a credibility crisis. For the first time ever, more Americans view the court unfavorably then favorably. A string of unpopular decisions and ethics scandals have combined to polarize opinions on the justices, doing away with the court’s longtime sheen of nonpartisanship. A recent poll found that just 16% of the country has a “great deal of confidence” in the court; meanwhile, 70% said the justices “try to shape the law to fit their own ideologies.”

Inside the justices’ ornate courtroom, however, they do everything they can to project an image of stability and power. The nine justices peer down from an imposing mahogany bench. A velvet curtain looms behind them, with a golden clock hanging in midair. The room is held up by 30-foot marble columns and decorated by engravings of famous “lawgivers,” from Moses to Confucius.

The justices are accorded every ounce of the respect they sometimes fail to receive in public. Everyone stands and falls silent when they enter the room. When I was there on Monday, I saw a group of lawyers being reprimanded for putting their elbows on the table in front of them; as attendees filed out, I heard a security guard shushing some merely for talking on the stairwell. The justices — clad in matching black robes — work hard to appear united; in interviews, they call themselves a “family” and boast about how well they get along.

Occasionally, though, you can feel that facade beginning to crack — and Monday, the last day of a politically charged term, was one of those times.

The day began with levity. Shortly after the Supreme Court marshal announced the beginning of the day’s session (with the traditional “Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!”), Justice Amy Coney Barrett launched into explaining the court’s first opinion of the day, in Corner Post, Inc. v. Board of Governors, a case about suing federal regulators.

“Sorry, this is not one of the cases you’re waiting to hear, so I’ll be concise,” Barrett joked to the audience, which was composed of a few dozen lawyers, 19 reporters (myself included), guests of the justices (including Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s parents and Chief Justice John Roberts’ wife), and 50 members of the general public.

Everyone laughed, but Barrett wasn’t really kidding. After Corner Post was handed down, and then the opinion in Moody v. Net Choice, LLC (a social media case), Roberts announced: “I have the opinion of the court in No. 23-939, Trump v. United States.” Immediately, you could feel the vibe in the room shift. Audience members sat straight up, while reporters (“as if one organism,” in the words of The Washington Post) began rustling through papers and furiously scribbling.

Building suspense, Roberts took his sweet time getting to the verdict. But, eventually, the court’s conclusions on presidential immunity came into view. Essentially, the justices split the question into three:

For “official acts” within the president’s “exclusive sphere of constitutional authority,” presidents are accorded absolute immunity from prosecution.

For “unofficial acts,” presidents have no immunity.

For “official acts” outside of the president’s “core constitutional powers,” presidents have the presumption of immunity, but they can still theoretically be prosecuted after leaving office if the Justice Department can prove that bringing charges would not intrude on the “authority and functions” of the executive branch.

“The president is not above the law,” Roberts wrote in his opinion, which was joined by the other five conservative justices. “But Congress may not criminalize the president’s conduct in carrying out the responsibilities of the Executive Branch under the Constitution.”

As it applies to Trump’s January 6th indictment — from which the immunity case stems — the court sometimes identified in which bucket the former president’s alleged actions sat and other times did not. For example, Trump’s conversations with Justice Department officials about overturning the 2020 election were deemed absolutely-immune official acts. His conversations with then-Vice President Mike Pence were classified as presumptively immune. None of Trump’s conduct was explicitly declared as unofficial. The justices then sent the case back to the federal district court in D.C. to decide which parts of the indictment could and could not be prosecuted.

Once Roberts finished, Justice Sonia Sotomayor began reading from her dissent on behalf of the court’s three liberals. Again, the mood in the courtroom shifted. While Roberts had spoken impassively, Sotomayor’s voice was sharp and mournful. She shook her head repeatedly; at times, she looked directly at the conservative justices she was rebuking, unlike Roberts, who started straight ahead the entire time he spoke. (The justices mostly avoided her gaze. The proceedings are not televised, and the justices take advantage of that fact. Justice Clarence Thomas, for example, spent much of the session leaning so far back in his chair that his head was practically horizontal to the bench.)

“Saying it so doesn’t make it so,” Sotomayor began, a turn of phrase that does not appear in her dissent as written. In fact, the liberal justice peppered several lines throughout her 25-minute oration — by far, the longest of the day — that are absent from her published treatise.

It wasn’t always clear for whose benefit these rhetorical flourishes were added. The session was not live-streamed and a recording of it will not be made available until October. (Even then, the audio will not be found on supremecourt.gov. Aspiring listeners will have to navigate to the National Archives website to find it.) Was she speaking to the 50 members of the public in the room? For myself and my 18 colleagues in the press section, who could only use pen and paper to attempt to transcribe her words? Or to her colleagues on the bench, few of whom seemed to be listening that intently?

Whatever the reason, Sotomayor broke from the script of her dissent repeatedly. “Remember the indictment!” she exhorted at one point, urging listeners not to forget Trump’s alleged behavior. Roberts had already quoted from the indictment a few times — it was quite striking to hear the Chief Justice of the United States say that a former president allegedly “conspired to overturn” an election — but Sotomayor spoke much more searingly about January 6th, as we sat some 200 feet from the Capitol.

“The indictment paints a stark portrait of a president desperate to stay in power,” Sotomayor intoned gravely. If Trump’s behavior “does not easily and obviously clear the bar [of prosecutable conduct]… then it is hard to imagine what prosecution ever would,” she added.

As with her written response, Sotomayor did not mince words in her oral dissent, accusing the court majority of inventing an “atextual, ahistorical, and unjustifiable immunity” for presidents “out of wholecloth.”

Again, though, the most notable jabs were said only in the courtroom. At one point, Sotomayor seemed to implicitly suggest that the conservative justices — three of whom were appointed by Trump — were motivated by personal politics in their decisionmaking. As she excoriated the majority for not even rendering a decision on whether Trump’s work to organize fake elector slates was an official or unofficial act, Sotomayor stopped to pose a question to the audience. “Why is it a hard question?” she asked. “I don’t know. Do you?” She let the question hang in the air, unanswered.

The session felt all the more contentious because Sotomayor wasn’t the only liberal justice who verbally lashed her colleagues Monday. Jackson also delivered an oral dissent — usually a rare step, reserved only for the most passionate disagreements — after Barrett’s opinion in Corner Post.

During Jackson and Barrett’s back-and-forth over Corner Post, as well as Roberts’ and Sotomayor in Trump v. United States, it sometimes felt like the liberal and conservatives justices were talking about different cases entirely. When Barrett spoke about Corner Post, she apologized for boring the courtroom; indeed, her opinion was highly legalistic. “For the non-lawyers in the room…” she said at one point, adding in some helpful definitions. She spent a solid chunk of time debating the meaning of the word “accrue.”

When Jackson spoke, however, she used little of her time to talk about the facts of the specific case — which involved a North Dakota truck stop suing over regulation on debit card swipe fees — and focused on the broader consequences of the ruling, which Barrett mostly obscured.

In Jackson’s telling, Corner Post was essentially a sequel to the court’s decision last week in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, which overturned the deference that courts have accorded to agencies in disputes over regulations. “You might think” that Loper Bright applies only to future regulations, Jackson said (like Sotomayor, speaking in second-person), without disturbing decades-old regulations that industries rely on. “Well if you thought that,” Jackson added, “because of today’s decision — the court’s holding in this case — you would be wrong.”

While Barrett presented the case as boring, Jackson warned that its implications would be “staggering,” doing away with the six-year statute of limitations after which regulations have historically been safe from legal challenges. “Any regulation about any issue can be put on the chopping block,” she said.

Similarly, Roberts sought to downplay the immunity ruling, arguing that the court had not gone as far as Trump had asked them to. Sotomayor pushed back: “The court gives former President Trump all the immunity he asks for, and more.” She went on to warn of the consequences of the ruling, as she saw them, creating a paradigm in which the president would be free to order Navy SEALs to murder a political rival, among other hypothetically immune “official acts.”

In his opinion, Roberts dismissed the “tone of chilling doom” of Sotomayor’s dissent, arguing that it was “wholly disproportionate” to the court’s ruling. In truth, however, both justices painted dueling apocalyptic portraits — each arguing that their colleague was dramatizing one fair and underestimating the other. Roberts warned that, without some presumption of immunity, the U.S. would cycle towards George Washington’s warned “alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge,” with each outgoing president hemmed in by the fear of prosecution by their successor.

“The end result would be an Executive Branch that cannibalizes itself,” Roberts said. Sotomayor, meanwhile, warned that the majority had turned the president into a “king above the law.”

Both Sotomayor and Jackson — who shared some rhetorical devices, such as repeating “Never mind that…” when invoking evidence in their favor that they accused the majority of looking past — pointedly attempted to use the conservative court’s originalist philosophies against them. Jackson, charging that the court’s ruling in Corner Post was “baseless,” accused the majority of contradicting the “indisputable intent” of those who wrote the relevant statutes.

Sotomayor was even more direct, invoking statements from the Founders to accuse the conservatives of dropping their reverence towards history and tradition when it didn’t suit them. “Interesting,” she said, in another aside delivered only orally. “History matters, right? Except here.”

The liberal dissenters turned to such snark and sarcasm at several points; with each jab, it became harder and harder to believe the court’s professions of cross-ideological harmony.

The court is still a place steeped in tradition, so some signs of tension were obvious — such as Sotomayor seeming to paint her colleagues as hypocritical political actors — while others were more subtle. One was that both Sotomayor and Jackson read dissents from the bench at all: traditionally, justices only do so to signal the most serious of disagreements. (Jackson only delivered two oral dissents this term, while Sotomayor offered three.) Dressed in black, the justices have few ways to express themselves sartorially. Still, The Post noted, Jackson wore a “chunky white, beaded statement necklace,” notably reminiscent of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s famed dissent collar.

Then, there is another custom the liberal justices flouted, one that may seem small but for an institution like the Supreme Court, amounts to a slap in the face. Justices typically close their dissenting opinions by saying “I respectfully dissent”; this tradition has been broken before, in cases like Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and Bush v. Gore, but it is done so very rarely.

Both Sotomayor and Jackson (in a separate response to Trump v. United States, which she didn’t read aloud) dropped the signal of respect in their dissents. Sotomayor went one step further. “With fear for our democracy,” she finished her opinion, “I dissent.”

Even after a contentious day, Monday ended at the court as it began: with laughter. When Roberts spoke after Sotomayor to close out the term — returning to his monotone delivery, even after her passionate dissent — he attempted to thank the Supreme Court employees, on behalf of his colleagues.

Instead, he initially said, “On behalf of my employees…” before stopping to catch himself: “My colleagues!” Even a few of the justices cracked smiles. Then, Roberts banged his gavel and a buzzer sounded; the Supreme Court is done until October.

Some “out of office” time seems to be coming at precisely the right moment. Whatever the justices are, colleagues or employees, after Monday, it was hard not to feel like they were operating in a fairly hostile workplace.

This one report justifies my paid subscription. Thank you, Gabe.

A ridiculously cool behind the scenes look, Gabe. So unique to WUTP. Thank you.