Humpty Dumpty Laws

Donald Trump vs. the Dictionary

“I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’” Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. “Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!’”

“But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument,’” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

Imagine you went into a coma on January 19, 2025 and just woke up today.

It is my job to fill you in on all you missed.

After telling you about the important stuff — like Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce — I’d then zoom out a bit.

Here, it would be my sober duty to inform you that, since you were asleep, America’s southern border came “under attack.” Our national security became “compromised” by trade deficits. The city of Los Angeles engaged in “a form of rebellion,” while the nation’s capital erupted in “lawlessness.” And a Venezuelan gang you’ve probably never heard of “invaded” our country.

At this point, even those of you who haven’t been in a coma for the past seven months might be a bit surprised. Really? All of that happened, right under our noses?

According to the president, yes.

Is he the one who gets to decide? Great question.

As I’ve written, rather than saying the Supreme Court has endorsed or rejected President Trump’s agenda, it’s more accurate to take cases category by category and look at each area of jurisprudence.

On cases that implicate the president’s power to fire executive branch officials, for example, we certainly have enough data to say the court is willing to give Trump carte blanche. Ditto cases involving DOGE and executive data. On cases involving federal spending, the court has largely punted, using procedural reasons to say the cases must be decided later. On cases involving due process for migrants, Trump has mostly lost.

There’s another category of cases, which has yet to reach the justices, that I’m especially curious to see how they rule on. These are disputes springing from laws that give the president special powers, as long as he utters a string of magic words declaring that some situation or another is in effect. How do we know if the situation is really happening, or if the president is just saying it? And are courts even allowed to second-guess him? The laws are usually vague; these cases will, often for the first time, offer answers.

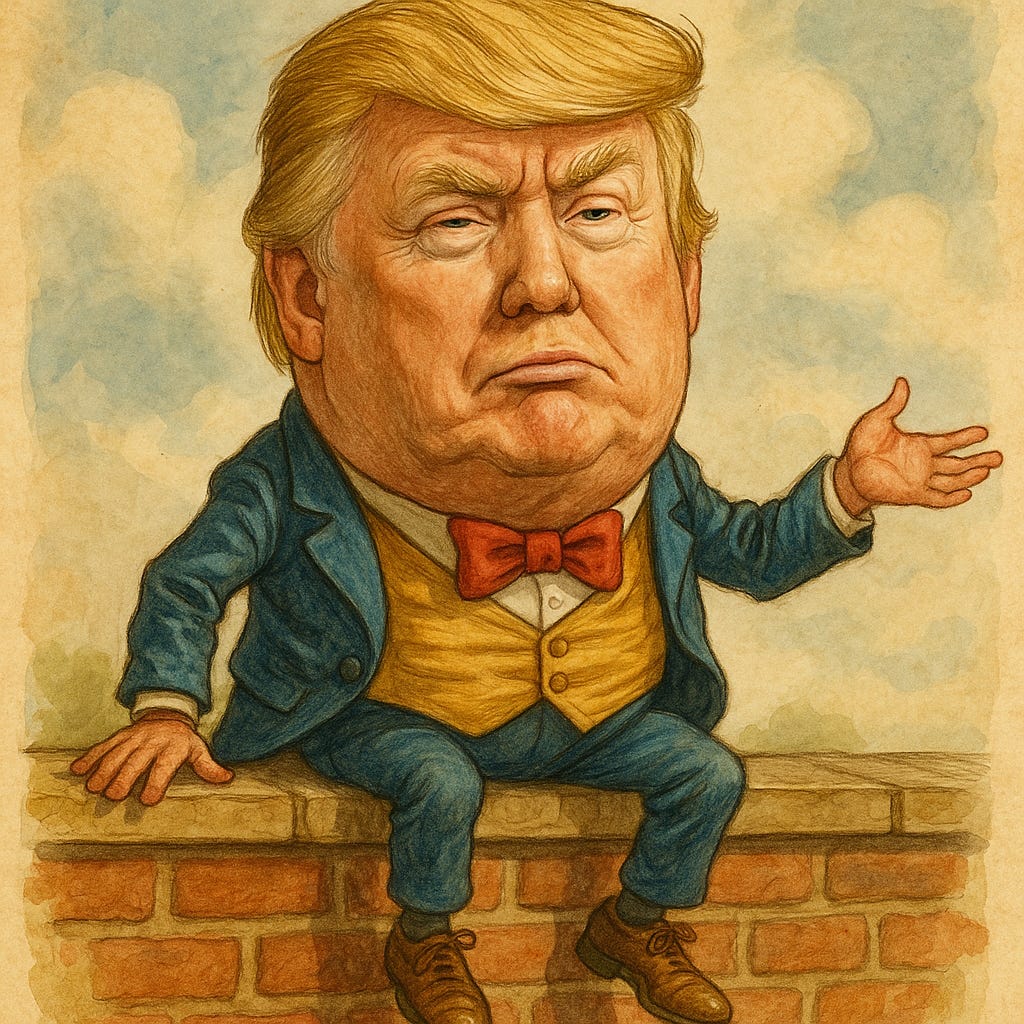

I call these Humpty Dumpty Laws, after the egg-shaped character in “Through the Looking-Glass” (Lewis Carroll’s 1871 sequel to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”), who tells a confused Alice that a word “means just what I choose it to mean.”1 In a series of cases advancing across the country, we are learning whether the U.S. president has similar word-defining powers.

One Humpty Dumpty case saw a major development just last night. That was the Fifth Circuit’s ruling in one of the many lawsuits over whether Trump properly invoked the Alien Enemies Act (AEA) of 1798, which gives the president increased deportation powers when a foreign government has declared war or launched an “invasion or predatory incursion” against the United States.

Trump signed a proclamation in March declaring that the gang Tren de Aragua (with support from Venezuela, which is how he got around the “foreign government” part) was invading the U.S., which he then used to deport Venezuelans who were alleged (without due process) of being TdA members to El Salvador. His attorneys have argued that, under the AEA, federal courts cannot question his determination.

Last night, a Fifth Circuit panel became the first appellate judges to disagree, joining several district court judges. Using 18th-century dictionary definitions and other writings from the era, two judges (appointed by George W. Bush and Joe Biden) ruled that an “invasion” is “an act of war involving the entry into this country by a military force of or at least directed by another country or nation, with a hostile intent,” while a “predatory incursion” describes “armed forces of some size and cohesion, engaged in something less than an invasion, whose objectives could vary widely, and are directed by a foreign government or nation.”

Actions by Tren de Aragua fit neither bill, the judges ruled; the U.S. is not being invaded, they said, and the president must have a factual basis if he says so. A third judge, appointed by Trump, dissented: he ruled that “the president’s declaration of an invasion, insurrection, or incursion is conclusive” and “completely beyond the second-guessing powers of unelected federal judges.”

The dissenting judge accused the majority of treating Trump like “some run-of-the-mill plaintiff in a breach-of-contract case” who must haggle over definitions. The president does wield some Humpty Dumpty powers, the judge effectively said: an invasion means what he says it means.

Trump’s attempt to fire Federal Reserve governor (?) Lisa Cook is another Humpty Dumpty case. In this dispute, Trump is drawing on the Federal Reserve Act (FRA) of 1913, which allows the president to fire Fed governors “for cause,” without offering any further indication of what type of conduct meets that bar.

In a Tuesday court filing, Cook’s lawyers draw on dictionaries, legal precedents, and other texts to argue that “the prevailing understanding of ‘cause’ at the time the FRA was enacted encompassed almost exclusively conduct undertaken in the course of office,” which would mean that Trump’s justification (allegations that Cook committed mortgage fraud before joining the Fed board) would not qualify. Even if it did, they add, the Supreme Court has previously held (in the context of another statute) that if an official is fired for a specific cause, “the officer is entitled to notice and a hearing,” which Cook did not receive.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, citing a different Supreme Court precedent, which found that removal for cause “is a matter of discretion and not reviewable,” argues that a president’s determination of cause is “conclusive,” end of story.

This question lacks an easy answer precisely because, according to University of Virginia law professor Aditya Bamzai, only two other presidents have ever tried to remove officials “for cause”: William Howard Taft and Richard Nixon.

In Taft’s case, he appointed a three-person “committee of inquiry” to investigate two members of the Board of General Appraisers, following complaints about their conduct. (One member of the investigative panel was future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, in what was his first major government role.) The committee held a public hearing and interviewed members of the board and other witnesses. Ultimately, the panel recommended that Taft fire one board member for using his position for personal gain and another for lacking qualifications and imbibing too much alcohol. On his final day in office, Taft fired them both.

Nixon dismissed the head of Fannie Mae without engaging in a similar investigative process.

Is Trump bound by the precedent set by Taft, who interpreted “cause” as requiring a months-long process of hearings and interviews? Or is “cause” whatever he says it is? In all likelihood, it will ultimately be the Supreme Court that decides.

There are many other examples of similar cases. Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs present a potential Humpty Dumpty problem: their legal underpinning is the declaration of a national emergency pegged to trade deficits. At a Federal Circuit hearing that I attended last month, several judges questioned whether such an emergency, in fact, existed.

When the Trump administration’s lawyer insisted that the president’s tariff powers were limited, because they could only be imposed during an emergency, but also argued that courts couldn’t second-guess the existence of an emergency, one judge responded: “If [the limits are] not reviewable, how are they limits?”

“Can a trade deficit be an ‘extraordinary and unusual’ threat” — the statutory threshold for an emergency — “when we’ve had trade deficits for decades?” another judge asked.

Ultimately, when the Federal Circuit handed down its decision last week, the judges did rule against Trump’s tariffs — but they didn’t rule on the question of whether a national emergency existed (or whether they had the power to rule on that). Instead, they ruled that the law Trump used didn’t authorize sweeping tariffs in the first place, national emergency or not, which made the Humpty Dumpty question moot.

Trump’s use of the National Guard in Los Angeles also poses a similar dilemma. Here, the president invoked the Militia Act of 1903, which allows the president to deploy the National Guard if “there is a rebellion or danger of a rebellion against the authority of the Government of the United States.”

In June, Trump declared that such a rebellion was taking place at immigration protests in LA. Shortly thereafter, Judge Charles Breyer (yes, his brother was also a well-known jurist) looked at several dictionary definitions and decided that a rebellion must be “violent,” “armed,” “organized, “open and avowed,” and “against the government as a whole.”

The protests in Los Angeles fall far short of ‘rebellion,’” Breyer ruled. A judge in Washington, D.C., has hinted at a potential similar examination, saying that she planned to hold a full evidentiary hearing to examine whether Trump’s proclaimed “crime emergency” in the capital is supported by crime statistics in the city.

“Humpty Dumpty” is obviously a humorous character to invoke, but my point here isn’t to poke fun at Trump or to suggest that his invocations of any of these laws are correct or incorrect. That will be for judges, and ultimately the Supreme Court, to decide.

All of these laws are very vague: they generally say the president can do X in the case of Y, without giving any definition of Y. In general, that probably makes sense: these statutes all contemplate emergency-like situations, which might be hard to specifically envision or define, where the president does need some flexibility to respond quickly, in a way Congress never could. This is why we have a president.

It is reasonable to think that the president should receive wide berth in deciding what is or isn’t an invasion: in a true invasion-like scenario, we wouldn’t want to be waiting on a court to decide whether the commander-in-chief can take swift action.

At the same time, it is easy to see how these powers could be abused, and it also seems reasonable to contemplate some role for the judiciary in litigating these matters, being careful not to step on the president’s toes when necessary while simultaneously ensuring that a president isn’t just creating an emergency out of thin air.

“The declaration of a national emergency is not a talisman enabling the President to rewrite the tariff schedules,” the predecessor court to the Federal Circuit wrote in 1975, in an important precedent for the tariff case. There should probably be some middle ground between constantly stopping the president from carrying out his duties, and allowing him to assert extraordinary powers simply by clicking his heels three times and invoking a set of magic words. (Sorry, I guess now we’re entered Oz, not Wonderland.)

All the way back in 1689, John Locke foresaw this issue, writing that legislative bodies are simply “too numerous” and “too slow” to address crises, which meant executives would need expanded powers in emergencies.

He acknowledged the possibility for abuse, but didn’t feel there was much that could be done about it. “There can be no judge on earth” for this question, he wrote. “The people have no other remedy in this… but to appeal to heaven” for rulers who will use emergency powers wisely.

In recent weeks, a string of litigants have argued that there can be a “judge on earth” for these matters: judges. Several courts have taken them up on it, often using the classic textualist approach of mining dictionaries to see whether the president’s use of various words (“rebellion”; “invasion”; “cause”) comport with the meaning of those words as understood by those who wrote them into key statutes. (As the liberal Justice Elena Kagan once said, acknowledging the dominance of this conservative approach: “We’re all textualists now.”)

The scope and powers of the American presidency hangs in the balance. If the Supreme Court ultimately agrees with Locke, and rules that no one can question the president on these matters — not even them — Trump will bequeath to his successor a much-expanded office, one that can impose tariffs, deploy the National Guard, and fire central bankers without the need to offer factual evidence to support his determinations.

Alternatively, if Trump loses on these scores, the presidency will be diminished — not because it will have lost powers its previous holders understood it to have (in most cases, presidents do not appear to have thought they had the authorities Trump is claiming) but because it will signal a renewed era of judicial skepticism towards the executive branch.

Historically, the executive has received a presumption of regularity from judges, a default assumption that they are telling the truth and conducting themselves honestly. “At bottom,” wrote Judge Andrew Oldham, the Trump appointee who dissented in last night’s Alien Enemies Act ruling, “today’s decision boils down to this: The majority, plaintiffs, and amici all urge that we cannot trust the President.”

When the president makes a determination, can judges trust him by default? Do words generally mean what he says they mean, even if great power comes with those words? In the coming months, a string of cases will offer answers to those questions, either leaving future presidents with expanded powers — even over language — or casting them as a “run-of-the-mill plaintiff” who has to contend with dictionary definitions like everyone else.

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

I first came up with the idea for this piece (including the title) last Tuesday, and I have the Notes app receipts to prove it. Last Friday, Abbe Lowell — who is representing the potentially-fired Fed governor Lisa Cook — invoked the same idea at a court hearing: “The court has to make a choice,” he said. “Either [the phrase ‘for cause’] means nothing, in which the president decided what ‘cause’ means when he says it, like Humpty Dumpty deciding what a word means when he says it.” You can decide who gets the credit.

Once again, I am in awe of your highly intelligent, thoughtful writing and reporting. You do a great job of teasing out the complicated intricacies of our government processes. What you do has never been more important. Keep doing what you’re doing. And thank you.

“today’s decision boils down to this: The majority, plaintiffs, and amici all urge that we cannot trust the President.”

That's right. And Trump is responsible for this.