How We Got to a Government Shutdown

And how we might get out of it.

If I were refereeing Washington’s current fiscal showdown — set to culminate in a government shutdown at the stroke of midnight tonight, barring some act of a furlough-fearing God — I would award four red cards.

The first three would go to Republicans. One would be for approving a rescissions package in July, clawing back $9.4 billion in funds that had been appropriated to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). There was nothing illegal about this — in fact, it was perfectly legal, done according to the process established by the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 — but it’s easy to understand how it would poison negotiations with the Democrats. Essentially, the move allowed the GOP to take last year’s spending bill, which required 60 votes, and undo parts of it with only 51 votes, sending a clear signal that any future bipartisan deal could be subject to partisan adjustment.

The second would be for taking that one step further, with the Trump administration’s pocket rescissions gambit in late August. This move subverts the normal rescissions process, proposing cuts (in this case, $4.9 billion of them) just before the end of a fiscal year, theoretically freeing the administration from the need to spend the funds without receiving sign-off from Congress. A district court order — kept in place by an appeals court — ruled the move to be illegal, but the Supreme Court paused the order, which means the fiscal year will end tonight without Trump having spent the funds.

The third GOP foul are the moves the president has taken, outside of the rescissions process (pocketed or otherwise), to not spend funds approved by Congress. According to congressional Democrats, this includes more than $410 billion in funding that the administration blocked this fiscal year; the Government Accountability Office (GAO), Congress’ in-house auditor, has now said seven times that Trump has illegally impounded (declined to spend) funds. The agency has dozens of other open investigations.

And then, finally, the Democratic red card: their insistence on including partisan policy demands in a continuing resolution (CR), a measure that’s supposed to be a stopgap funding bill. Like the first GOP red card, there is no argument that can be made that this is against the law — the legality of the other two GOP fouls is contested — but it nonetheless is something that was obviously going to take us out of the normal appropriations rhythm.

By “normal” rhythm, I don’t mean Congress passing all 12 appropriations bills by October 1. That never happens anymore, and it wasn’t going to this year. But, in modern times — except for years with a shutdown — legislators have fallen into a pretty standard pattern of approving fairly “clean” CRs as a way to buy time to continue bipartisan spending talks. The idea, usually, is that the big policy negotiations will take place around the appropriations bills; the CR is just a time to kick the can down the road until you get there.

The 13 CRs passed with bipartisan support during the Biden years (see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here) all followed this basic model, doing nothing more than extending funding and occasionally serving as vehicles for bipartisan priorities (like disaster relief or Ukraine aid). The government never shut down as a result. A CR usually just isn’t the time to stage a partisan fight, since it’s hard to complain that negotiations haven’t gone your way … when you’re still in the middle of the negotiations. Sure, maybe throw a fit if you don’t like the policy that comes out of the eventual appropriations bills — but at least wait for them to be written first. To extend the sports metaphors, it’s akin to refusing to play the rest of a game while still very much in halftime.

Of course, as I explained, it isn’t only thanks to Democrats that the “normal” appropriations process has gotten out of whack this year — all four red cards have gotten us there — even if they are the ones pulling the trigger by refusing to vote for a mostly “clean” CR. (The Republican-proposed stopgap would add security funding for government officials, the same sort of bipartisan additions made to these measures during the Biden era.) And the Democratic gambit might not qualify as an appropriations foul of its own if it was being done purely as a corrective to the GOP subversions to the process, but the party’s proposed CR does much more than merely undo (and block) rescissions: it also calls for an indefinite change to health care policy (permanently extending the expanded Obamacare premium tax credits) and the repeal of chunks of the Republicans’ signature legislative package, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

This sort of gives away the game, in that Democrats do have a fair argument that Republicans have been tampering with the appropriations process all year — but, let’s face it, the shutdown that will start tonight isn’t about that. And that’s the case for at least two reasons: because, politically, Democrats know that health care makes for a much more salient talking point than rescissions (try fitting “reform the Impoundment Control Act” on a bumper sticker) and, really, members of the party’s base have been pushing for a shutdown all year as a way to register their broader frustrations about Trump and weren’t going to let Chuck Schumer avoid one this time.

And, again, this is not illegal! The idea that CRs should be used as a simple, non-partisan stopgap between appropriations bills is an informal social contract, and it’s one that Republicans have tried to break in the past. Democrats are free to violate it now. But no one shouldn’t be surprised by Republicans responding exactly as Democrats have in those instances, by saying: We’re not going to have a major policy negotiation — certainly not over undoing our signature legislative accomplishment — attached to a routine CR. Nice try.

The irony here is that, for all the fouls flying in both directions, the regular, bipartisan appropriations talks (the ones that a CR is supposed to be buying time for) have actually been humming along pretty civilly this year, at least in the Senate.

The Senate Appropriations Committee has passed eight of the 12 spending bills, all with bipartisan support. (One was approved 27-0. The others received, at most, three dissenters, except for the Commerce-Justice-Science bill, which passed 19-10 due to a dispute over the FBI building.) And despite Republicans boasting a majority, Democrats were not doing horribly in these negotiations!

They succeeded in protecting funding for the National Science Foundation and the National Weather Service, both targeted by the Trump administration, in the Commerce-Justice-Science bill. And blocking proposed Trump cuts to the Labor Department, Education Department, and National Institutes of Health in a bill approved 26-3 by committee. And keeping the GAO, another Trump enemy, funded in a bill approved 26-1. And even reviving environmental justice programs in a bill approved 26-2. What’s more, several of these measures added guardrails to prevent Trump impoundments, by including detailed tables and instructions that would normally have been put in non-binding reports directly in the legislative text.

(Three takeaways: #1: Progressives are correct that the appropriations process affords Democrats leverage, due to the Senate filibuster, but that doesn’t mean they are correct that a shutdown is the most effective way to use it. #2: Much of the funding being slashed by Trump has bipartisan buy-in — after all, Republicans voted for it last year — but Republicans just needed a way to quietly support it, through the appropriations process, rather than noisily stand up to the president. #3: Yes, it’s true that Trump could try to impound any of the funds in the above bills. But it’s also not clear that a shutdown will achieve anything that will stop him from impounding either. Instead, the best path to doing so is probably through the courts, and continuing with these bipartisan appropriations bills likely would have improved the Democrats’ legal arguments, especially since Senate Republicans were open to including more explicit instructions in this year’s round of spending packages.)

To be clear, these bipartisan appropriations bills being approved by Senate committee does not guarantee that they would have become law. The Republican-led House, as is its custom, was advancing in a much more partisan fashion: this year’s process could have gone like Fiscal Year 2024, when the Senate passed bipartisan bills and the House passed partisan bills, and then the eventual packages looked much more like the Senate’s; or Fiscal Year 2025, when the Senate passed bipartisan bills and the House passed partisan bills, and then the two chambers couldn’t agree, so they merely passed a full-year CR (although even that had the effect of prolonging the bipartisan spending levels from FY 2024).

Still, the point here is that the appropriations process was proceeding exactly as it has the past several years — and, not only was the Senate process proving to be perfectly bipartisan, it was even seeking to correct one of the GOP fouls by working to prevent impoundments. Even if the bipartisan Senate bills weren’t going to be the exact final product (they never are), this seems like an odd time to junk the negotiations entirely and go home.

But, then again, the Democratic base didn’t want bipartisan negotiations, even ones that might have produced favorable policy outcomes. It wanted a fight. Now, it is getting one.

Every fight has to come to a close eventually, though: we might be headed for a long shutdown, but nobody thinks it will be a permanent one. So, as the shutdown is about to start, it’s worth considering how it might end.

Here, there are two overlapping conversations: how it will end politically, and how it will end in terms of policy.

Politically speaking, Democrats enter the shutdown starting from a relatively strong position. A New York Times poll out today shows that only 19% of registered voters say they would blame Democrats for a shutdown, compared to 26% who say they would blame Donald Trump and Republicans and 33% who say they would blame both parties equally. (21% say they haven’t heard enough to say.) A Morning Consult poll also found more voters prepared to blame Republicans than Democrats.

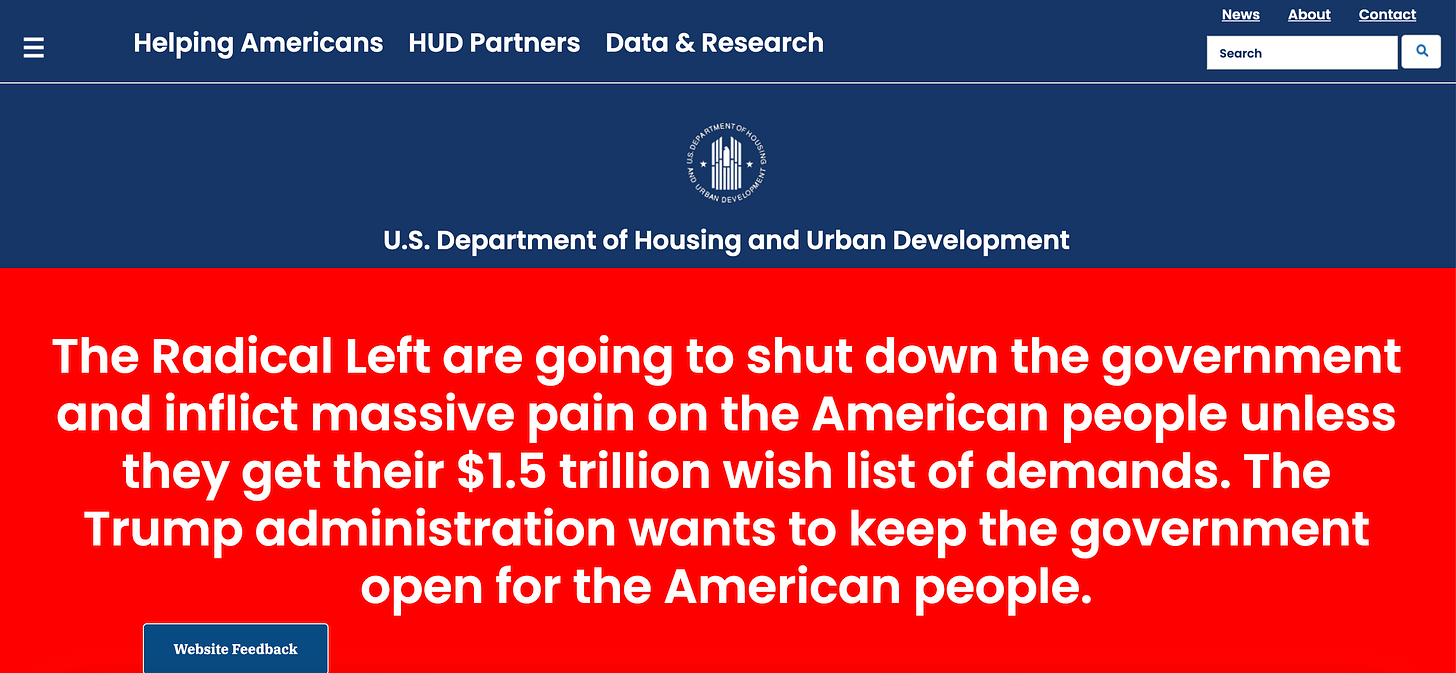

This could always change, however. Both parties will now spend the coming days trying as hard as they can to pin the shutdown on the other — a goal Trump will likely use the full force of the federal government to advance. (Below, see the current home page of the Department of Housing and Urban Development website.) We’ll see if those numbers change as the effects of the shutdown become real, and as the dueling partisan messaging machines kick into gear.

Historically speaking, I can tell you that the party making demands during a shutdown (here, the Democrats) usually exits the shutdown with worse poll numbers, although the slump rarely lasts long enough to impact the next elections.

Similarly, all I can say on the policy angle is that historically, parties trying to enact policy change via shutdowns fail to do so.

In 1995 and 1996, Newt Gingrich led Republicans into two government shutdowns; all he got out of them was a non-binding plan from Bill Clinton to balance the budget in seven years, a plan Republicans ended up not even liking. In 2013, Ted Cruz led Republicans into a shutdown, demanding that Democrats repeal Obamacare. Instead, the GOP won very minor changes to the law. At the start of 2018, Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi shut down the government over immigration legislation; after a three-day shutdown, all they secured was a Republican commitment to hold a vote on their desired bill. (The vote was held; the bill failed.) Then, at the end of 2018, Trump pushed a shutdown of his own, demanding funding for his border wall. Congress ended up appropriating only $1.4 billion for border fencing (out of $5.7 billion Trump had wanted), though Trump later declared a national emergency to try to unlock the funding unilaterally.

A shutdown is usually staged as a symbolic fight; as a result, parties usually only win symbolic prizes.

Here, that could look like a Republican commitment to vote on an Obamacare subsidies package, or even a commitment to negotiate a package by a certain date. Both are escape hatches that will likely be discussed in the coming days.

The political side interacts with the policy side, of course. Exiting a meeting at the White House yesterday, Democrats had clearly settled on a strategy to try to pit President Trump and congressional Republicans against each other.

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) told reporters that there was a “real division” between Trump and his congressional deputies, with the president (in Schumer’s account) expressing openness to a deal on Obamacare subsidies.

Democrats are hoping that the public will blame Trump for a shutdown, he will get antsy about the polls, and they will be able to take advantage of his loose ideological commitments and occasional desire to strike bipartisan deals to get him to accept an agreement on Obamacare that the more reflexively conservative Republican leaders don’t want. This play could work, turning a political win into a policy victory, though it generally hasn’t in recent history, if only because the party pushing a shutdown doesn’t usually receive the polling advantage that they imagine. These are, however, strange times: existing dissatisfaction with Trump could lead the normal dynamics of who is blamed for a shutdown to be inverted; and normally parties aren’t negotiating with a president as ideologically heterodox as Trump.

Then again, there are also short-term policy considerations at play, and these can sometimes run counter to the political side of the coin. As I’ve written, President Trump has extensive power to dictate what remains open and closed during a shutdown, and he has already threatened to take full advantage of it. This could actually help the Democratic political case, if Trump begins laying off more government workers than is necessary during a shutdown and voters blame him for it, not the Democrats. But that would come at the cost of their short-term policy interests, since Democrats (and their allied interest groups) don’t historically like seeing a smaller government workforce. All it will take for the shutdown to end is seven Democratic senators who eventually decide that the short-term policy losses — even if they’re producing a political win — aren’t worth holding out for a potential longer-term policy victory that might never materialize.

Republicans will likely make Senate Democrats take this vote again and again in the coming days (and maybe weeks), forcing them to run this calculation over and over in their heads, balancing the short- and long-term politics with their desired short- and long-term state of public policy. How long will America’s big-government party carry on a crusade that will have the effect of shrinking the bureaucracy? Stay tuned to find out.

Thank you Mr. Fleisher, I got a lot out of this essay. Your point/counterpoint analysis was spot on. Just as an aside…not sure if anyone remembers those kids books back in the day where you could “choose your own story?” At different points in the book you were asked what you think would happen next, and when you chose, the book would lead you to a certain ending. Then if you went back and chose a different possibility for what would happen then the book led you to a different ending. Your essay made me smile (in spite of the tragedy of what present events are) because it reminded me of those books. I sure used them with my students when I was teaching.

I don't understand why you keep making comparisons to past outcomes when the current situation is anything but normal!