How do Obamacare Subsidies Work?

Separating fact from talking points.

Happy Friday, everyone! Over the last month, two government programs in particular have received outsized attention: the enhanced Affordable Care Act premium tax credits, better known as “Obamacare subsidies,” and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, better known as “SNAP” or “food stamps.”

The enhanced Obamacare subsidies have been in the news because extending them was the Democrats’ main demand for funding the government. (The demand was ultimately not met). And food stamps were being discussed because they were at risk during the subsequent shutdown. (There was a contingency fund that could have funded some — though not all — SNAP benefits during the shutdown, which the Trump administration declined to use.)

Both these programs have been the subject of a lot of political conversation lately. But this week, while soliciting questions for today’s Q&A post, I received two questions that essentially boiled down to: How do they each work?

And it occurred to me that it would potentially have been very easy to closely follow the debates on both these topics — the ups and downs, the various bills introduced, the legal battles — and even to have a strong opinion on these debates, without necessarily being grounded in the exact specifics, since most news outlets will tell you the latest micro-development (Congressman X Signals Openness to Enhanced Obamacare Subsidy Extension) but not always back up and make sure you know what the enhanced subsidies are in the first place.

Which is fair enough, that’s their job! But here at Wake Up To Politics, I view it as my job to help you understand your government at a nitty-gritty level, so that you can be as informed a citizen as possible. So, in a two-part series, we’re going to wipe away all the partisan talking points and take a straightforward look at what, exactly, politicians are talking about when they talk about Obamacare subsidies and SNAP, to make sure that you are able to follow these debates with all the context and nuance they deserve.

We’ll tackle Obamacare subsidies today, and SNAP next week. Normally these Friday Q&A posts are paywalled, but when I do these sorts of civic-minded explainers (like peeling back the curtain on what Congress is actually doing, or my six-part Reader’s Guide to the Big Beautiful Bill), I like to make them free for all — even though those are generally the pieces that require the most research. So, today’s piece will be un-paywalled, too.

But: if you find yourself learning something below, and if you’re able, please consider creating a paid subscription in order to support my ability to provide this sort of work.

And, even if you’re not able to pay right now, maybe send this newsletter to a friend and tell them about Wake Up To Politics?

Your support is so appreciated: WUTP is 100% independent, so it’s truly the only thing that keeps this project going. And now: let’s dive into the weeds of Obamacare subsidies (and, soon, SNAP): what they are, how they work, and where they stand now that the shutdown has come to an end.

Obamacare subsidies

Q: In regards to the health care subsidies, what is the benefit of getting rid of them? I don’t even know how they work really. Was the government literally paying the insurance companies to cover people? If that’s true, what happens to all the money that the government was paying insurance companies? Does this reduce the trillions of dollars in debt? What is the benefit/gain here?

First, let’s frame the universe we’re talking about.

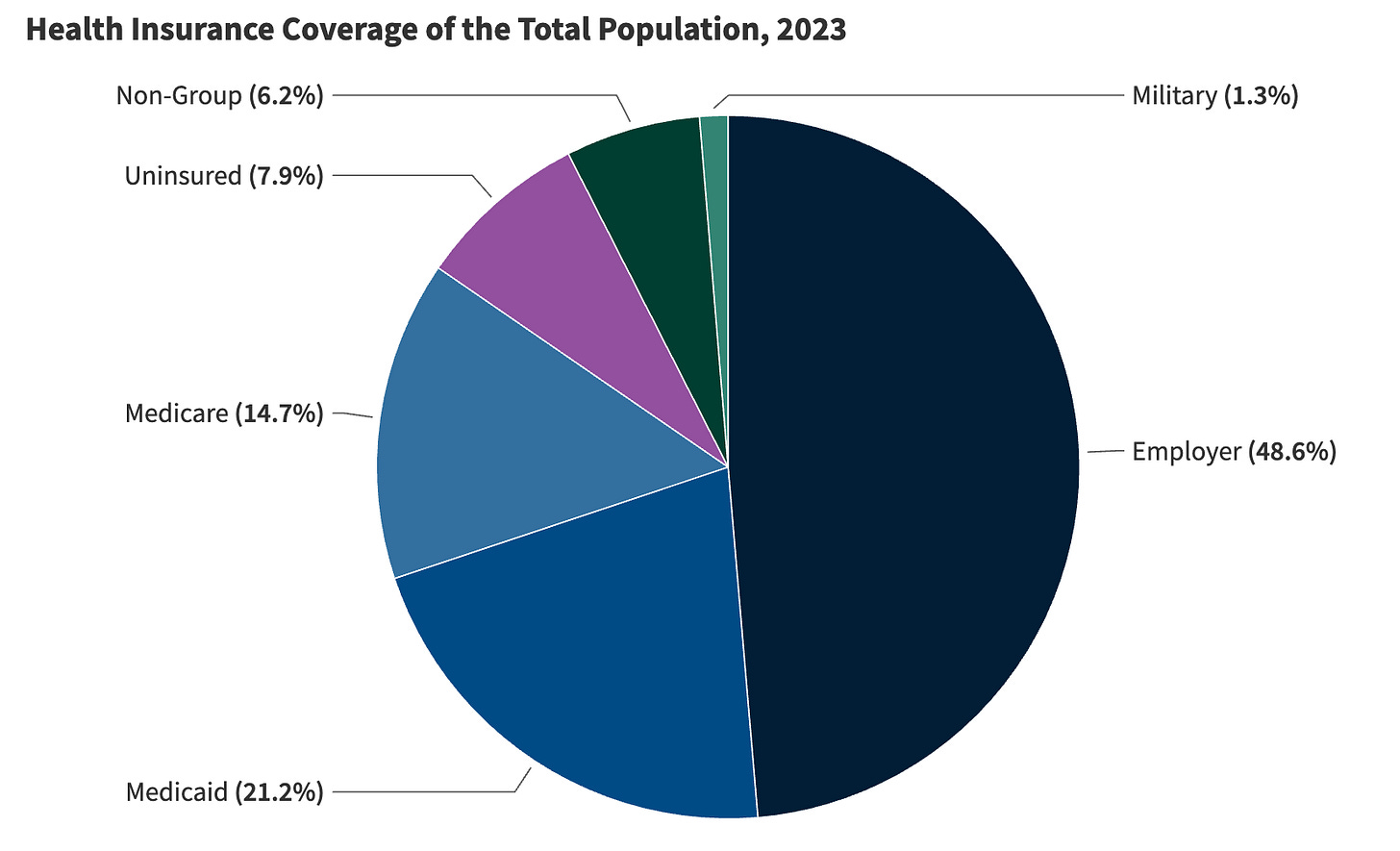

This chart from KFF, a non-partisan health policy research group, will help ground us in the various ways Americans receive health insurance, at least as of 2023. Around 8% were uninsured. Around 86% were insured through their employer, Medicare, Medicaid, or TRICARE, the military insurance program. When we talk about Obamacare, we’re talking about the 6.2% in the “non-group” category below.

Use this chart as a benchmark, not as an exact percentage, because there are some people in the non-group category above who purchased insurance through means other than the exchanges set up by the Affordable Care Act (aka the “ACA” aka “Obamacare”), and also because there has been an uptick in ACA enrollment since 2023. (The ACA exchanges, also known as “Marketplaces,” are an online tool that allow otherwise uninsured people to directly purchase health insurance for themselves after comparing different government-regulated options. 17 states have set up their own exchanges; the others use healthcare.gov, the federal marketplace.)

The most exact, up-to-date numbers are that 24.3 million Americans — around 7% of the country — purchased health insurance through the ACA exchanges for 2025. But even this isn’t our proper universe yet for discussing the current Obamacare subsidy fight, because not everyone who buys their insurance through Obamacare also receives government assistance to pay for that insurance and what’s at issue right now isn’t that assistance itself, it’s a new layer of assistance that was added to Obamacare during the Biden era.

Didn’t quite follow that? Let me explain.

When the Affordable Care Act was first signed into law in 2010, it included premium tax credits (also referred to as “PTCs” or “Obamacare subsidies”) that would help subsidize the cost of monthly premiums for health insurance purchased through the new exchanges.

These tax credits were only available to people whose incomes were between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level. (Currently, for a single individual, that would be anyone whose annual income is between $15,650 and $62,600. For a family of four, that would be a household income between $32,150 and $128,600.) As of 2020, the average tax credit recipient was receiving $5,942 annually, out of an average $7,132 they owed towards their premiums. (They were on the hook for the $1,190 difference.)

The American Rescue Plan Act, signed into law by Joe Biden in 2021, expanded eligibility for the tax credits (by eliminating the upper income cap that had been set at 400% of the federal poverty level), and also made them more generous.

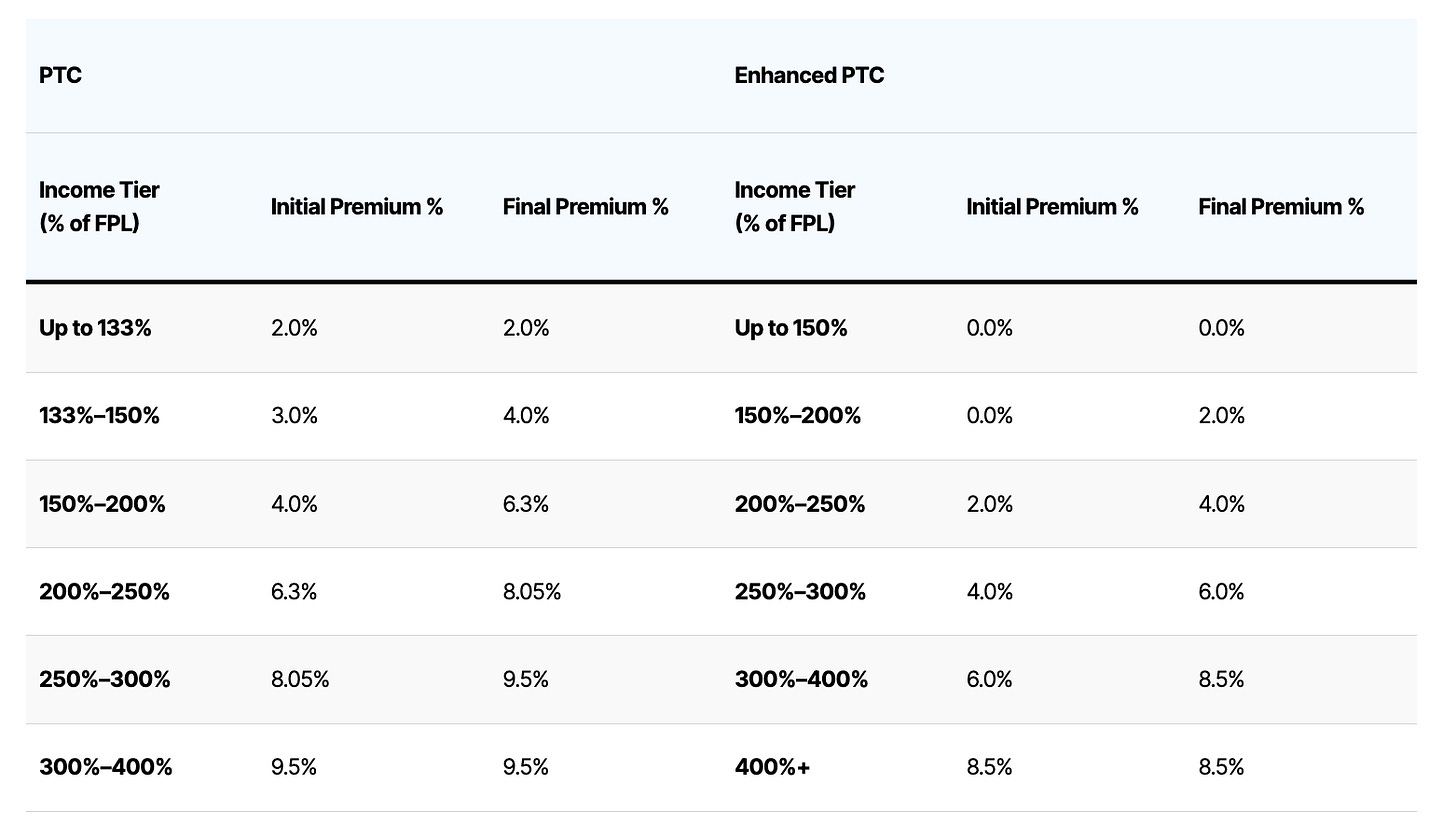

How much more generous? The tax credits rely on a sliding scale, whereby the government subsidizes recipients to ensure that no more than a certain percentage of their income has to go towards their monthly premium payments. (The recipient is assumed to be purchasing a “benchmark” Obamacare plan.) Here’s a chart from the Bipartisan Policy Center, which shows the range of contributions towards their premiums that people are expected to pay at each income tier, under both the original tax credits and the enhanced tax credits.

So, for example, the tax credits were initially sized to ensure that someone whose income is 200% of the federal poverty level would be spending, at most, 6.3% of their income towards their premiums; the enhanced tax credits knocked that down to 2%.

These enhanced tax credits were initially structured as a two-year measure, set to expire on December 31, 2022. Then, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, extended them for three more years, creating a new expiration date of December 31, 2025. That’s where we find ourselves now.

On average, per KFF, the premium tax credits grew in size by $705 under the enhancement, going from the government paying about 83% of the average recipient’s premium costs in 2020 to about 88% in 2024. The changes also led to several millions more people enrolling in Obamacare, now that the attendant subsidies made the cost of that insurance less expensive.

Now, let’s return to looking at how (and how many) people are impacted by the enhanced tax credit’s potential expiration.

We said before that 24.3 million Americans buy their health insurance through Obamacare. Of these, 22.4 million have that insurance subsidized through the premium tax credits.

92% of Obamacare enrollees have incomes below 400% of the poverty level, so their tax credits are poised to be reduced if the enhanced subsidies are not renewed, but they will still be eligible for the tax credits from the original Obamacare law. The other 8% have incomes above 400% of the poverty level, so they will lose their eligibility for premium tax credits completely.

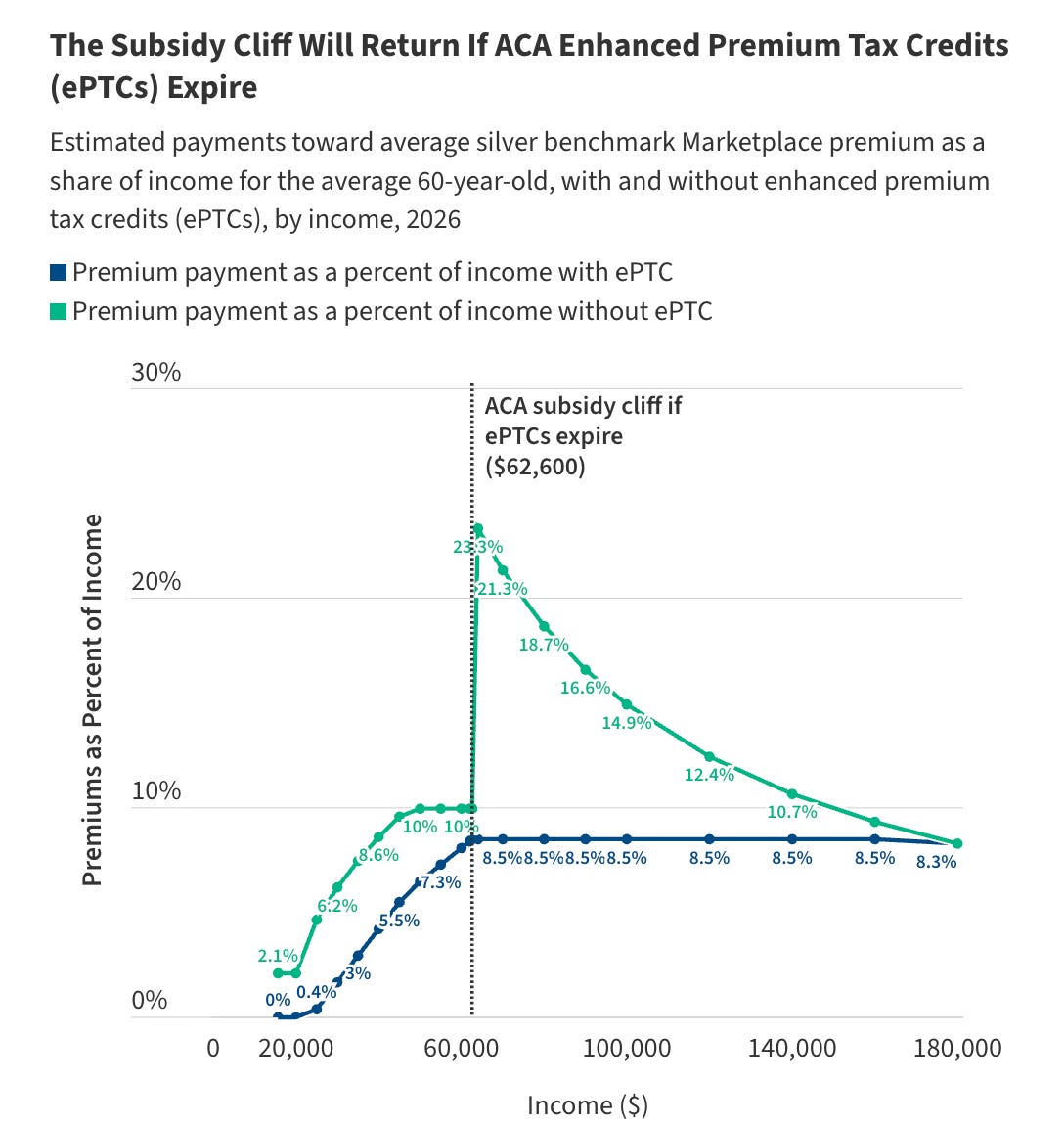

This is the main group you’re hearing about whose premium payments are about to shoot up the most, because the end of the tax credits would revive something known as the “subsidy cliff.” Essentially, premium costs will look a lot different to people on either end of the 400%-of-the-poverty-level threshold.

KFF uses the example of an average 60-year-old earning $62,000 a year (396% of the federal poverty level). They would have to pay $5,208 in annual premium costs out-of-pocket if the enhanced subsides are extended, and $6,180 if they aren’t (a difference of $972).

But then consider an average 60-year-old earning $64,000 a year (409% of the poverty level). They would have to pay $5,436 in annual premium costs if the enhanced subsides are extended, because their out-of-pocket costs would continue to be capped at 8.5% of their income. But if the enhanced subsidies aren’t extended, they wouldn’t be eligible for subsidies at all — suddenly, their annual premium payments would shoot up to $14,928. Their annual income is only $2,000 more than the person in our first example, but their premium costs have increased by about $8,520 more than the increase we saw in our first example.

Here is the “subsidy cliff” rendered in a graphic by KFF:

Many, many words later, and I still haven’t answered what my questioner was asking. Oops. So, now that we know what the tax credits are, how are they distributed?

Yes, they are generally sent directly to the insurance companies. The premium tax credits (enhanced or otherwise) are advanceable, which means the recipient can choose for the tax credits to be automatically applied to their health insurance premiums each month.

If a recipient chooses this, the amount of money that the government owes the recipient is simply sent directly to the recipient’s insurance company each month, and wiped away from the total cost of the premium bill sent to the recipient.

This does open up an opportunity for mischief, because it requires people to estimate their income for the year ahead, so the government can calculate how much to pay your insurance company each month (instead of you paying each month, then reporting your actual income to the government, and the government giving you a credit at the end of the tax year).

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office estimates that 2.3 million people “improperly claimed the premium tax credit via intentional overstatement of income” in 2025, based on an “unusual concentration of enrollees reporting income just above” the federal poverty level. (Recall that your income has to be at least 100% of the federal poverty level to qualify.) The One Big Beautiful Bill Act included measures aimed at cracking down on these improper payments.

The premium tax credits aren’t all taken as an advance. A recipient can also choose to pay their premiums themselves each month, and then have the government pay them back one big lump sum at the end of the year. But the vast majority of PTC recipients don’t take this option, because they’d rather have help month to month with their large premium bills than be on the hook for those costs in the moment and only receive assistance down the line.

President Trump has recently criticized this feature of the subsidy program, writing that government funds should go “DIRECTLY TO THE PEOPLE” instead of to “THE ‘FAT CAT’ INSURANCE COMPANIES.” It is unclear exactly what the president is proposing, although Republican lawmakers like Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-LA) have interpreted Trump’s message to indicate support for their proposals to create federally funded accounts for each American, allowing people to pay directly for their health expenses rather than go through insurance companies.

As CNN reports, there is no consensus within the Republican Party on what such a plan would look like and to what degree it would replace Obamacare — would protections for people with pre-existing conditions be maintained, for example? Cassidy, for example, argues that a broader fix is necessary: the fact that the enhanced subsides are necessary in the first place show that the Affordable Care Act wasn’t affordable, and extending them would be like “putting a band-aid on a broken bone,” he says. Cassidy believes the moment calls for restructuring Obamacare entirely.

However, there isn’t much time for a wholesale rewrite of health care law — at least not before people need to lock themselves into an Obamacare plan, or before they start seeing heightened premium costs. The enhanced premium tax credits expire on December 31. Open enrollment for the Obamacare exchanges ends on January 15 — and enrollees need to sign up even earlier (by December 15) to receive coverage that starts on January 1. (Theoretically, if the premium tax credits are extended after January 1, lawmakers could retroactively apply them for the time period that was missed.)

According to NBC, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) is urging his fellow Republicans to use the reconciliation process to advance a health care plan that wouldn’t require Democratic votes. But this would be virtually impossible to pull off by next month, which means a bipartisan agreement is likely the only viable option for a fix before costs start to rise.

The Congressional Budget Office projects that the number of uninsured Americans would increase, on average, by 3.8 million each year over the next 10 years if the enhanced tax credits are not extended, because people with big premium increases would likely drop out of the insurance market entirely. This, in turn, would make insurance more expensive for everyone else, because insurance relies on the participation of young, healthy people spreading out costs across a more balanced risk pool, rather than one that’s made up only of older, sicker people with much more expensive care.

Separately from the Obamacare subsidies, insurers are also expected to increase health care premiums significantly next year, which means premium costs are likely to go up regardless for many — but, of course, they will go up more without the heightened subsidies. All in all, KFF estimates that the average tax credit recipient will pay $1,016 more in premiums next year in a world where the enhanced subsidies aren’t extended vs. a world where they are, taking into account the fact that premium costs will be going up in either event.

To, again, return to the question at hand, people being hit with smaller cost increases are the “pro” of extending the enhanced subsidies.

The questioner also asked about the “con” in terms of the costs to the government (or, that is, the taxpayer — the $1,016 still has to be paid if the enhanced subsides are extended, it’s just coming from a different source). The questioner specifically asked if ending the enhanced subsidies and going back to the previous subsidy level “would reduce the trillions of dollars in debt.”

The answer is yes, any time the government stops spending its money on something, that means it doesn’t need to take out as much debt, because it won’t be running as high of a deficit (the annual difference between how much money the government spends and how much it receives) as it was otherwise going to. (Assuming that it doesn’t merely increase spending elsewhere to offset the savings.)

Every expenditure has the possibility to reduce government spending (and, therefore, that year’s deficit and the broader debt level) if eliminated — but some expenditures contribute more to government spending than others, of course.

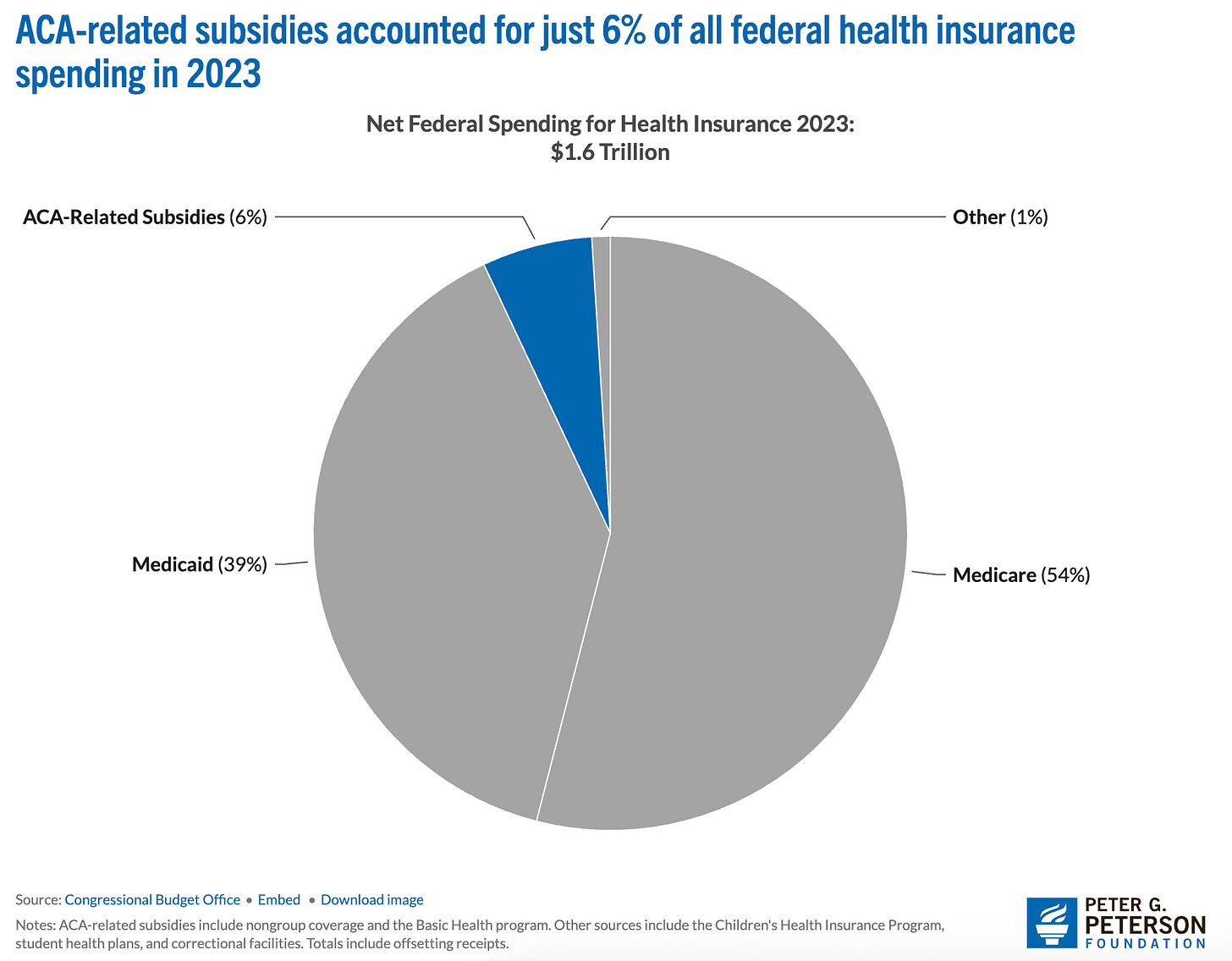

The federal government spends about $7 trillion a year, and about $91 billion of it went towards Obamacare subsidies as of 2023. That’s about 1.3% of the federal budget, or — as the below chart from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation shows — about 6% of federal health care spending.

That means the note I started on cuts both ways: just like how, when we’re talking about Obamacare subsidy recipients, we’re talking about a relatively small segment of Americans — that also means we’re talking about a relatively small segment of federal spending. The real culprits for the deficit are Medicare and Medicaid, which are much more widely used.

And, of course, just like how not everyone who receives Obamacare tax credits will see their tax credits disappear if the enhanced subsidies aren’t extended (though many will see their tax credits reduced), the 6% in that pie chart above won’t magically disappear on December 31 — because the original Obamacare tax credits will still exist.

So really lawmakers are arguing over a fraction of that 6% (which is itself just a fraction of the larger budget, since the pie chart above only shows federal health insurance spending).

In total, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that extending the enhanced Obamacare subsidies would cost around $30 billion each year for the next few years, and then around $40 billion a year if they were extended into the 2030s. So that’s how much they would add to the deficit (currently at $1.9 trillion) each year if extended, or how much you could imagine them subtracting (compared to a world where they’re extended) if they are allowed to expire.

Of course, every dollar being added to the deficit counts — just as every person seeing lower health care costs does — so none of this is an argument in terms of what should happen one way or the other. But hopefully this primer has helped explain what exactly the enhanced subsidies are, and offered some useful context on how many people stand to be impacted on the one side and how much of the budget is at stake on the other.

In my next part of this series, I’ll be answering this question I received on SNAP:

Q: Can you do an investigative piece on the SNAP program? It is a $100 billion dollar/yr program that one in eight Americans apparently receive. Over 40 million Americans, every month. That sounds hard to believe. What are the qualifications for receiving the assistance?

Stay tuned. If you appreciated today’s explainer, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my ability to provide these sort of pieces:

Thanks for reading, and have a great weekend.

The ACA as originally conceived included a mandate that all Americans obtain health insurance. That meant that anyone not covered by their employer or Medicare or some other way would have to purchase health insurance through heath insurance exchanges. Everyone. The idea was that the premiums would be affordable because the pool would be large and would include healthy young people. The Republicans objected to this universal mandate and in order to get the bill passed it was stripped out. Young healthy people did not participate and premiums were therefore higher than originally anticipated. That’s how the Affordable Care Act became unaffordable. It’s been so ever since and the situation just gets worse and worse. A quick and easy fix would be to reintroduce the mandate. It’s a tough sell politically but anything else is even tougher which is why the Republicans have not come up with a plan of their own.

There are some other things to compare in this

Twenty years ago my wife and I were self employed I paid 750 per quarter for insurance with a 2500 dollar deductible for each I'm sure that cost has gone up

I was a recruiter for many years Some people could not change jobs because insurers would not insure pre existing conditions With the new bill, to the largest extent, that would be the case again

People that lose their jobs generally have to go on COBRA to have insurance Even with a short unemployment there is typically a waiting period to get insurance again

With 24 million Americans buying their own insurance, using a very conservative additional cost of 1K each per month I believe that works out to almost 250 trillion a year

A lot of the elderly will be put into pools that have a higher cost

Hospitals and clinics are mandated to see anyone

Preventive medicine reduces medical cost

These are the real costs were looking at