How Congress Could Eat the Presidency

What if lawmakers wanted more, not less, power?

Welcome to Part 2 of our deep dive into Trump v. Slaughter, the landmark Supreme Court argument on independent agencies — and the separation of powers — that I attended on Monday. Part 1 is here.

We left off yesterday with the conservative justices grilling Amit Agarwal, the lawyer for the ousted Federal Trade Commission (FTC) member Rebecca Slaughter, on the logical extension of his argument that Congress can exercise significant control over the agencies that it sets up for the executive branch. If that’s the case, could these controls apply to the core Cabinet departments, not just to independent agencies?

“Could Congress convert all these departments into multi-member commissions — Commerce, EPA, Department of Homeland Security, Department of State — convert them all into multi-member commissions and make them removable only for cause?” Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked. “The SG was asked about the logic of his argument,” Justice Clarence Thomas said, referring to Solicitor General John Sauer, who was arguing opposite Agarwal. “What’s the logic of yours? How far does it carry you?”

Let’s attempt to answer that now.

I.

Imagine, difficult as it may be, a power-hungry Mike Johnson. Imagine, as our Founders expected (and then to an even higher degree), he was leading a Congress that was obsessed with being partisans, not for a specific political movement, but for their own branch of government.

Maybe, by some string of miracles, these members belong to a Congress Party that has won overwhelming (and veto-proof) majorities of the House and Senate based solely on the premise that our system of government needs to be restructured in the legislature’s favor. This requires the suspension of quite a bit of disbelief, but it will help us flesh out the outer bounds of what our system might (and might not) allow.

How would this monomaniacal Speaker Johnson and his members go about their task? They would start by referring to the Constitution, of course. Pretty quickly, as discussed yesterday, they would find that the document is practically silent on what the executive branch should look like. The Constitution’s executive branch firmly establishes a president, a vice president, and no one else — and even the vice president’s sole constitutional obligation (presiding over the Senate) belongs within the legislative, not executive, branch.

The millions of other people who make up the modern government (the agencies, the political appointees, the civil servants) are basically absent from the founding charter. Even the Cabinet, which we now think of as a collection of the government’s senior-most officials, is only hinted at. Article II, Section 2 says that the president can seek “the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments,” but it does not identify any such departments or even grant them any real duties beyond giving the president written advice upon request.

Delegates at the Constitutional Convention were split on how powerful to make the presidency; “the vacuousness of Article II,” Yale Law professor Jerry Mashaw has written, was the product of their compromise. The Constitution “left a hole where administration might have been,” according to Mashaw, and punted to Congress to fill it in.

Let’s say our modern Congress Party is generous. They scan what is written in Article II and allow the president to keep those Cabinet departments clearly prescribed therein. The president is made “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy”? OK, he can keep the Department of Defense. (They’ll even let him keep the Marine Corps, as a treat.) He is given appointment power (with Senate confirmation) over an undefined group of “Ambassadors” and “other public Ministers and Consuls”? Sure, let him have the State Department. And, of course, the president is told to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”? Give him the Department of Justice.

Although the Constitution certainly does not promise the president any additional personnel to carry out these tasks, the Congress Party is worried about legal trouble if they confiscate the departments that so directly carry out functions listed in the Constitution.

But after that? The renovation spree can start. We tend now to think of the government as synonymous with the executive branch, but there is no reason to assume the Founders would have agreed. Above, I have listed nearly all of the powers accorded to the president in Article II of the Constitution. Most other federal powers are listed in the much-longer, Congress-centric Article I.

“Congress shall have the power,” Article I, Section 8 tells us, to “lay and collect Taxes,” “borrow Money,” “coin Money,” “regulate Commerce,” “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” and so on. Congress, not the president. Most federal power is granted in these terms, and few instructions are given Congress for how to use its power.

So, yes, why couldn’t our hypothetical Congress announce that the departments that correspond with powers in its realm will now be multi-member commissions independent of the executive branch? Or, out of an abundance of caution — not that the separation of powers is made explicit in the Constitution either (otherwise, why would James Madison have thought an amendment was needed to do so, as we noted yesterday) — a scheme could be set up that tries to divide power more than yank it away.

The functions of our modern agencies could be divvied up: the Labor Commission and the Transportation Commission and so on could handle the rule-crafting and adjudication of disputes through administrative law judges that feel awfully legislative and judicial in nature, while departmental equivalents within the executive branch could continue the day-to-day administration of governmental programs. Actual decisionmaking would be left to Congress and, to the extent they delegated, the commissions; the executive branch departments would merely carry out what they were told, without any of the massive room for interpretation currently given.

Under the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, the president appoints “Officers of the United States,” and he could continue to nominate commission members, with Senate consent. (Although, it should be noted, the clause also says that “the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.” The difference between an “Officer” and an “inferior Officer” is, of course, not explained, though the Supreme Court has tried at various points.)

Prosecutions would remain within the executive branch; a big question would be what to do with civil law enforcement, which includes major penalties that agencies can currently impose. At the Supreme Court on Monday, Justice Alito imagined, as I have here, a Justice Department “split into two parts”: “One part has the authority to enforce the criminal laws, and the other part has the authority to enforce civil laws. Could Congress put at the head of the civil component a multi-member commission with removal protection?” Alito asked Agarwal.

Agarwal answered that “it’s not obvious that Congress could do that, and what we know for sure is that Congress has never tried to do that.”

II.

But previous Congresses have contemplated structuring the executive branch radically differently.

During the Trump v. Slaughter arguments, independent agencies were obviously treated highly skeptically by the conservative justices, and the idea that Congress could go even further and structure core Cabinet departments as multi-member commissions was repeatedly dispensed with even more mockery.

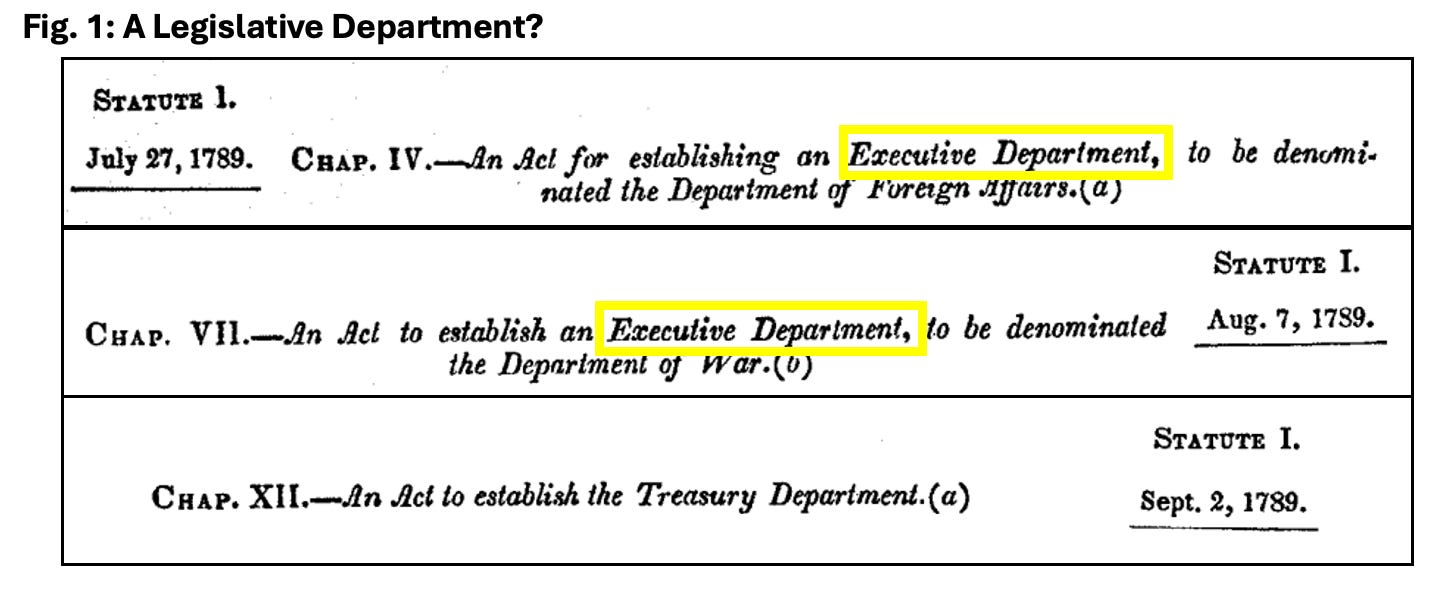

The first Congress, though, considered doing exactly that. Just like my hypothetical Congress Party, the original legislators agreed that certain powers were firmly in the presidential domain, and they quickly created the Departments of Foreign Affairs (now State) and War (now Defense1) to assist the president in these areas.

But it was not obvious to them that other administrative roles should be so structured. Take the future Treasury Department, for example. Foreign affairs and defense may have been mostly Article II powers, but Congress is given the power of the purse in Article I — not just the ability to appropriate, but also to “lay and collect Taxes,” “pay the Debts,” “borrow Money,” “coin Money,” and more.

As a result, there was widespread agreement that the Treasury Department couldn’t be given the same independence from Congress as the Foreign Affairs and War Departments, so much so that Massachusetts Rep. Elbridge Gerry (yes, of gerrymandering fame) proposed the department be led by, you guessed it, “a board of three commissioners,” just as had been done under the Articles of Confederation.

Although Gerry’s proposal was ultimately not adopted, there is no evidence the first Congress viewed the idea as contrary to the Constitution (and they would have known — many of the legislators, Gerry included, had been delegates at the Constitutional Convention).

In the end, the Treasury was made into a department — but was it an executive one? A keen eye will note that the statutes that created the Departments of War and Foreign Affairs refer to each as “an Executive Department.” No such label is given the Treasury.

As Henry Clay would note on the floor of the Senate in 1833: “Except the appointment of the officers with the cooperation of the Senate, and the power which is exercised of removing them, the President has neither by the Constitution nor by the law making the [Treasury] Department anything to do with it… The Secretary is required to report, not to the President, but to Congress.”

Indeed, the statute repeatedly mentions Congress, explicitly directing the Treasury Secretary to give various reports to legislators, but the president or other executive branch actors not at all.

According to Georgetown Law’s Josh Chafetz, “the Treasury was understood as being not simply a creation of Congress, but a continuing arm of Congress,” the embodiment of Congress’ pecuniary powers. When the department was established, the House (briefly) abolished its Ways and Means Committee, since it assumed the Treasury Department would play that role on its behalf.

There are other examples of the first Congress looking at executive power very differently than we do. My Congress Party handed the president prosecutorial power — but prosecutions were often carried out by private parties or court-appointed officials in the period after the Founding. As Mashaw notes, Congress initially kept a great deal of administrative power for itself; when citizens had issues with government pensions or other matters, they could petition Congress, which would consider the case and then pass private bills, which settled individual claims, one at a time.

Congress eventually began to delegate this work, but more out of convenience than concerns about the Constitution.

As time went on, lawmakers forked over more and more power to the president. But proposals continued to circulate to reimagine government and remind the Cabinet that they sprung, Athena-like, from the minds of Congress, not the president. After the Civil War, committees in the House (in 1864) and Senate (in 1881) approved bills that would have made Cabinet members into the equivalent of non-voting members of Congress, requiring them to regularly attend legislative proceedings and answer lawmakers’ questions.

Under the 1881 bill, Cabinet secretaries would have sat in the House on Mondays and Thursdays and in the Senate on Tuesdays and Fridays, answering any questions the chambers approved by resolution. Pete Hegseth’s weekly schedule would have looked a little different, huh?

A range of scholarly sources suggest that the proposal received support, at various times, from future, sitting, or former Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes, James Garfield, William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson, and Warren Harding, as well as the editorial board of the New York Times. The parliamentary-like “questions period” idea would later be revived after World War II by Estes Kefauver, the Tennessee senator and 1956 Democratic vice presidential nominee.

Such a proposal, the Times editorialized in 1864, would “make the Executive power more directly accountable” to Congress. “There is no good reason why our Congress should be the only representative body of any nation that is deprived of personal communication with those to whom is intrusted the administration of the affairs upon which the body legislates,” the newspaper added, saying that the proposal “would remedy a great defect in our national system of legislation.”

III.

OK, now we have wandered a bit afield from Trump v. Slaughter.

But I hope I’ve given proof that previous generations of lawmakers, to a much greater degree, viewed the Cabinet as at least partially in Congress’ domain: created by lawmakers and answerable to them.2

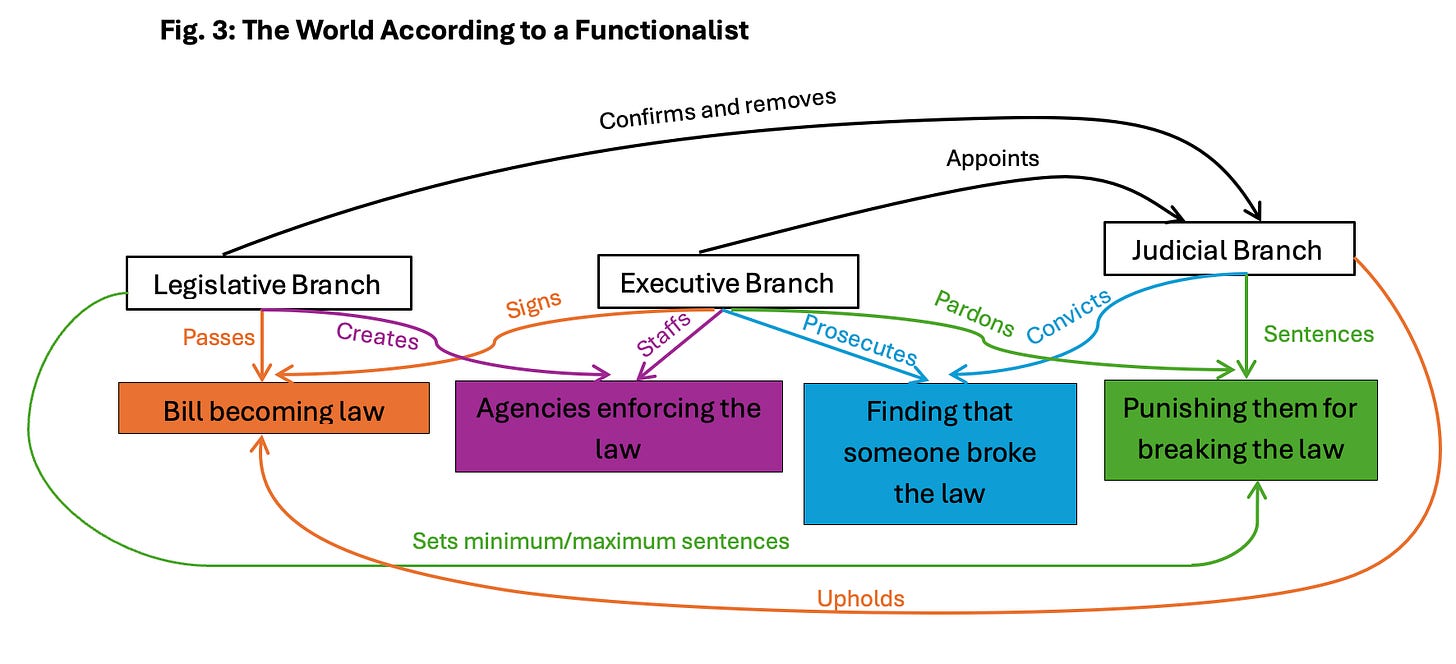

As I wrote yesterday, this reflects a more functionalist vision of government: a philosophy that supports more flexible power-sharing between the branches of government. My point here isn’t to endorse that vision, but merely to show that our current model of government isn’t the only one that’s been utilized, or considered, in the U.S. the last 230-odd years.

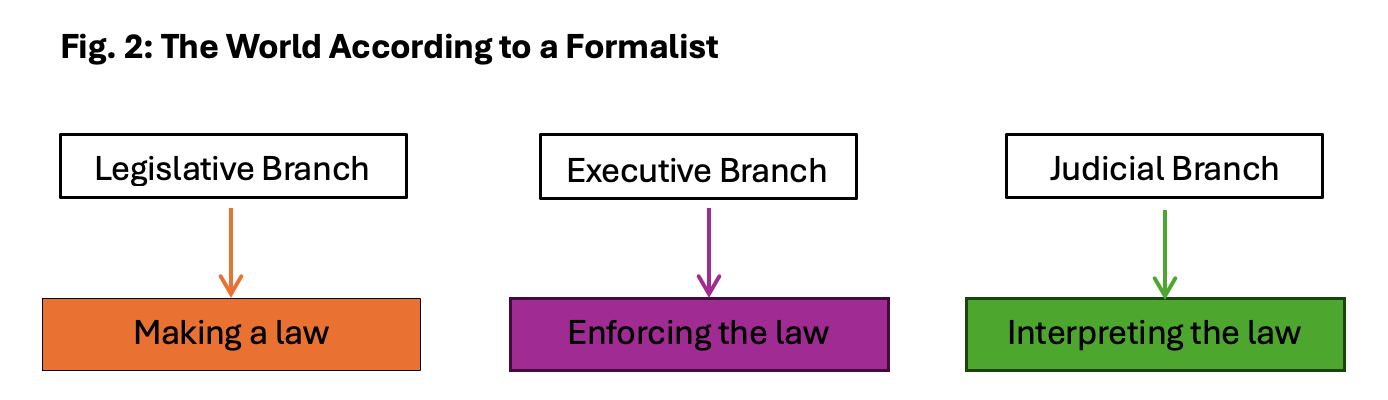

To be sure, there is history that bolsters the formalist case as well — and both sides of the debate can claim some backing in the Constitution, which is so vague on many of these points that much can be read into it. As their primary evidence, formalists point to the Vesting Clauses of Articles I, II, and III, the provisions that state legislative, executive, and judicial power are “vested” in the Congress, president, and Supreme Court, respectively. Which does sound pretty definitive!

Until you try to untangle some of the knots that functionalists point out: if legislative power is vested completely in the Congress, why give the president a veto? Or if executive power is vested completely in the president, why does Congress declare war?

The formalists also like to cite the Decision of 1789, which stems from debates the First Congress had when creating the aforementioned executive (or not) departments. When setting up these agencies, the House spent an entire month debating whether the secretaries of the departments would be removable by the president. Ultimately, the resulting statutes didn’t address the issue explicitly, but did explain what would be done with a secretary’s papers when they “shall be removed from office by the President of the United States,” which has been interpreted as evidence that Congress gave removal power to the president. (Functionalists dispute this interpretation of events.) Executive agencies, executive control. Everyone inside their boxes.

Functionalists, meanwhile, point to what they call the first independent agency, the Sinking Fund Commission, which Congress created in 1790 to make decisions about repaying the national debt. The commission consisted of three Cabinet secretaries (who are removable by the president, as we know) — but also the president of the Senate and the Chief Justice (who are not). Beep-beep, overlapping line alert!

Perhaps this merely means there weren’t many people around back then prepared to serve in government capacities. But it also reveals something of a more functionalist vision, with a commission that isn’t quite stationed in any branch and includes members from all three.3 (Formalists dispute this interpretation of events.)

Do we have separation of powers or checks and balances — two concepts we often cite together but which, if you think about, somewhat contradict each other? How do the branches check each other if not by using powers that are supposedly within the other branch’s sphere?

IV.

The Supreme Court did not object in 1789 when Congress structured the Treasury Department outside of the executive branch — but, then again, how could it? Congress hadn’t set it up yet.4

It was clear on Monday, however, that the current Supreme Court would not look kindly on such a structure, just as it will not be looking kindly on independent agencies.

A lot has been attached to that decision-in-the-making, but as I’ve tried to lay out in this column and yesterday’s, that really comes down to a philosophical divide between formalism and functionalism, of how you’d like to (and think you can) set up the government. There are some ideological dimensions there, but they are faint: as much about one’s tolerance level for fluidity and messiness as anything.

Duke Law professor Jeff Powell has called the divide between formalism and functionalism “the biggest substantive division in constitutional law that doesn’t have a moral side to it.” Although the decision in Trump v. Slaughter will have epic consequences for a range of issues, the right answer isn’t really attached to your opinion on any one of them — especially seeing as the impact it would have on those issues would change depending on who is in the White House. No one “side” would consistently come out on top. It is much more about governmental design than ideology.

Personally, there are elements I find appealing both about the efficiency of formalism and the flexibility of functionalism. (I’ve dwelled more on the functionalist side of the equation in this newsletter more as a fun way to consider the constitutional road not traveled, not because I think that’s necessarily the better road.5) The “right” answer on a practical level is probably somewhere in between.6 As I’ve laid out, I’m not sure there’s a “right” answer constitutionally, simply because the Constitution is so vague.

At different points, the Supreme Court has leaned more formalist (see: Myers, Chadha, and Seila Law) and functionalist (see: Humphrey’s Executor, Morrison, and Mistretta). In Morrison in 1988, the justices upheld an independent counsel position created by Congress which was appointed by a court and only removable by the executive branch for cause. The ruling was 7-1, with Justice Antonin Scalia writing in dissent that the Constitution does not give the president “some of the executive power,” he wrote, “but all of the executive power.”

Almost four decades later, Scalia’s dissent will likely become a majority stance.

This will be widely regarded as a victory for the unitary executive theory Scalia championed — but the decision is more accurately seen as a victory for formalism, a broader theory that pushes not just for executive power to be kept to the executive, but for legislative power to be kept to the legislature.

Considering the case in these terms, and the theory in full, is important, because it is in the latter application that President Trump might find his likely victory in Trump v. Slaughter matched with an equally bruising loss. I was struck during Monday’s oral arguments how frequently another pending case — the one surrounding President Trump’s tariffs — came up.

Warning about the scenario I described yesterday as Peak Congress, Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted Monday that “once the power’s taken away from the president, it’s very hard to get it back in the legislative process.”

“The real-world of this is the independent agencies shift power from the presidency to the Congress,” Kavanaugh added. “Everyone recognizes that Congress has more control over the independent agencies than they do over the executive agencies. Congress doesn’t want to give that up. It’s hard for the president to get new legislation passed that would, for example, convert an independent agency to an executive agency.”

It’s “kind of the flip side of what we were talking about in the tariff case,” Kavanaugh noted — where the justices warned that it would be hard for Congress to get back a quintessentially legislative function (imposing import taxes) once delegated, just as it would be difficult for the president to reclaim an executive function here.

Comments by Trump’s other two appointees on the bench, Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Neil Gorsuch, also suggested a court paying particular attention to separation of powers — potentially kicking not just the legislature back to its box in Slaughter, but the executive back to its box in the tariff case as well. Just as formalism contains unitary executive theory (upholding executive power in the executive sphere), it is also vast enough to include the major questions doctrine (which seeks to uphold legislative power in the legislative sphere).

Whether intended by the Framers or not, the lines of responsibility in our government have admittedly gotten a bit out of whack, overlapping ways that sometimes favor conservatives and sometimes liberals, and sometimes the executive and sometimes Congress. The third branch, the Supreme Court, seems very interested in straightening them out.

Or is it War again?

And we still see the lineage of that! Cabinet members still appear before congressional committees, of course, and Congress has vast power — should they use it — over executive branch agencies through their power over funding. Yesterday, for example, the House passed a bipartisan bill that would hold back a quarter of Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s travel budget until the Pentagon provides Congress with the full video of recent airstrikes against alleged drug boats.

Yes, the president of the Senate is also the vice president — but back in those days, the VP was seen as more a creature between the executive and legislative branches than firmly planted in the former. It’s telling, for instance, that the statute creating the fund refers to the VP’s legislative, not executive, title.

Yes, I probably should have mentioned that a really power-hungry Congress Party could start going after the judiciary, too: Article III says that there “shall” be a Supreme Court, but doesn’t set a size, and then leaves it to Congress to create any district or appeals courts. A one-person judicial branch anyone?

Yes, the Supreme Court would probably take issue with that — but I should also note that Congress is given considerable sway over the court’s jurisdiction and schedule. This is a great way to speedrun a constitutional crisis.

And because I think it’s fascinating that, even though our history has largely drifted towards more and more executive control, the recipe for complete congressional domination is more clearly spelled out in the Constitution.

Indeed, the Framers are often stereotyped as worrying about executive power — but this really scared them too. “The legislative department is everywhere extending the sphere of its activity, and drawing all power into its impetuous vortex,” James Madison wrote in the Federalist Papers. As if.

Indeed, the Supreme Court likely won’t go full formalist: its decision in Trump v. Slaughter is expected to carve out the Federal Reserve from presidential control.

I'm trying to see formalism working without the messy crossovers inherent in real problem solving...and failing. Short of writing an iron clad code that would address most all circumstance, I feel there would always be crossovers, hence functionalism. Functionalism seems to require mature, balanced, intelligent PEOPLE...that we trust to operate without every i dotted and t crossed in some rigid code.

I’m curious, how could the Supreme Court justify protecting the Fed while simultaneously stripping other agencies of independence?