Democrats have money to burn

And why it matters in a way you might not expect.

Good morning! It’s Monday, September 30, 2024. Election Day is 36 days away. The vice presidential debate is tomorrow.

The Democratic Party has more money than it knows what to do with.

I first became aware of this a few weeks ago, when I was in Philadelphia covering the first (only?) debate between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. Not only did the Harris campaign put on a drone show outside the city’s art museum for no apparent reason, but the city was also covered with digital billboards referencing Barack Obama’s R-rated joke about Trump (“Crowd size matters,” they declared, with two differently-sized pretzels to drive the point home.)

Meanwhile, on TV, Harris’ team paid for an ad playing on the same taunt, which ran locally that day on Fox News (Trump’s favorite channel) in precisely two media markets: West Palm Beach, where he started his day at Mar-Lago, and Philadelphia, where he spent the night for the debate. Harris has also run ads on Project 2025 and Trump’s ex-staffers who now oppose him specifically in West Palm Beach, spending an estimated $50,000 on one of the campaigns for the sole purpose of trolling a single viewer.

Before the debate, walking around outside, I also spotted this fleet of cars, which the campaign had apparently bought simply to drive around the city all night and inform everyone that Philly was “wit” Harris (a reference to the cheesesteak order).

By comparison, the only mark of Trump in Philly that day was a competing set of digital billboards — bought not by Trump’s campaign, but by a personal injury lawyer in Florida who has spent millions of dollars running his own personal ad campaign for the former president.

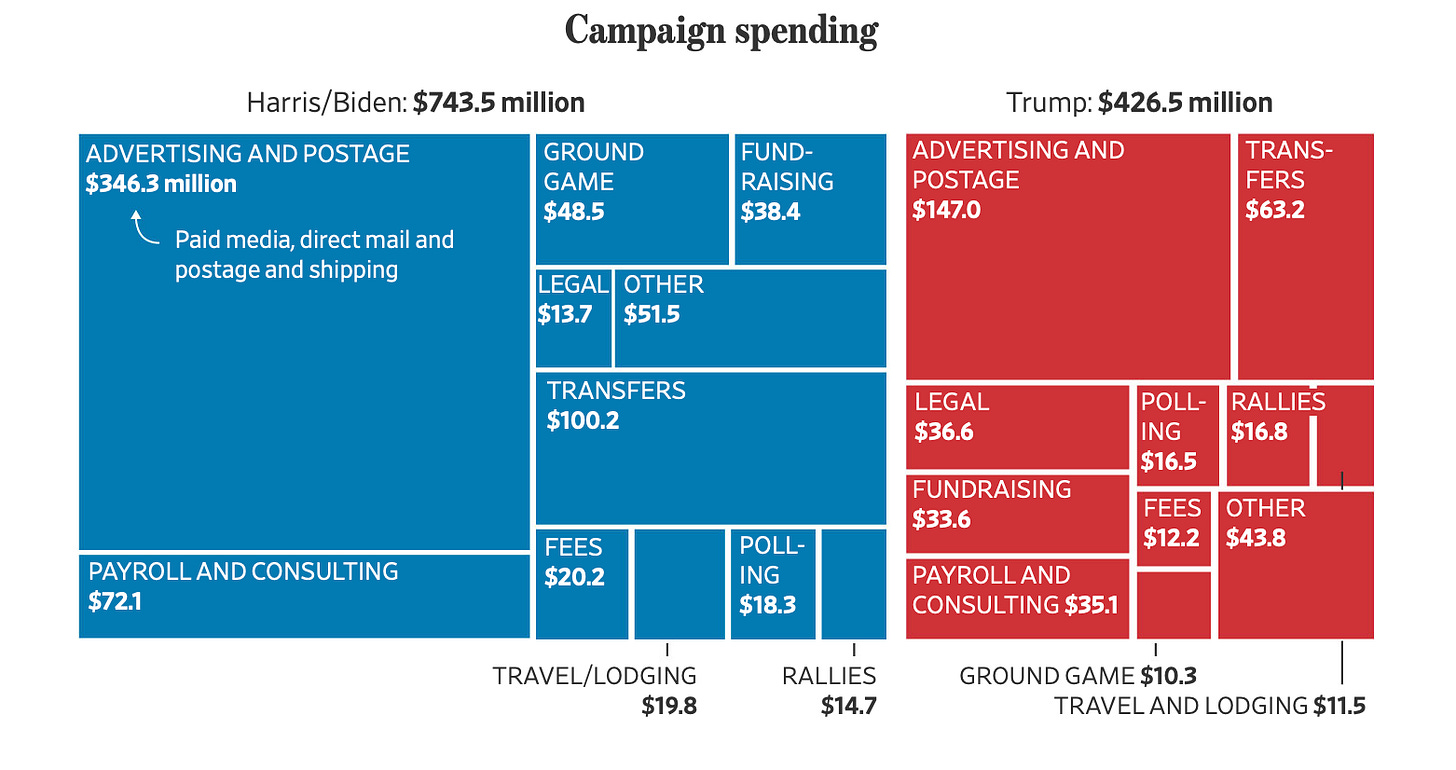

The disparity in the two campaigns’ war chests can be seen by more than just a couple of stunts in Philadelphia. Harris is massively outspending Trump — and doing so comfortably because she is also taking in much more money at the same time.

In August, the Harris campaign spent almost three times as much as Trump’s camp ($174 million to $61 million), but also raised so much ($190 million to his $45 million) that she ended the month with considerably more money in the bank ($235 million to his $135 million). As Bloomberg put it, Harris has so much money in her coffers that she is able to outspend Trump by nearly $5 million a day (and still have enough cash left over to spend some of it on drone shows and trollish ads).

Two questions emerge from all this: how did this happen and how much does it matter?

On the first point, much of Harris’ gargantuan advantage can simply be boiled down to the enthusiasm unleashed on the Democratic side after she replaced Joe Biden on the ticket. Harris raised $81 million in the first day of her campaign, $200 million in her first week, and $500 million in her first month — absolutely jaw-dropping numbers. More people donated to Harris’ campaign in her first 11 days than donated to Biden in his entire year running for re-election.

Donor enthusiasm for Trump has simply not kept pace. Back in May, his felony conviction in New York sparked a blockbuster fundraising day for the ex-president: nearly $53 million in 24 hours, much like each of his indictments did during the primaries. But he has struggled to recreate the magic since, even through a dominant debate performance in June and an assassination attempt and the Republican convention in July, all events that you might think would spark fundraising advantages for Trump but didn’t. (The gap is likely to continue growing in September. Harris raised $47 million in the 24 hours after her debate victory; Trump’s campaign did not release its post-debate haul, a sure sign that it was smaller.)1

Trump’s small-donor operation — once seen as the best in American politics — appears fatigued, taking in much less than it did in 2020 amid a torrent of appeals that some Republicans worry has overwhelmed his supporters. I’ve also been wondering of late about Trump’s growing number of side hustles: the $100,000 diamond watches, the new crypto business, the trading cards, the sneakers, the Bibles.

Obviously, it’s not mutually exclusive: Trump super-fans could be maxing out to his campaign and then buying their Trump Watches, but isn’t it possible that some are spending money on one and not the other (especially since buying the merchandise gives you a more tangible reward than the longer pay-off of contributing to a presidential campaign)? As one Trump friend reportedly told him, the GOP nominee has recently appeared distracted; perhaps some of his off-the-clock business ventures are also distracting his supporters, and swallowing up money that would otherwise be going to his re-election bid.

Now, onto the question of how much Harris’ fundraising and spending advantage means for her campaign. Of course, you’d always rather be the candidate with more than less — but recent history suggests that money doesn’t always determine success in presidential campaigns.

Trump himself has been outspent now in two previous presidential campaigns, one of which he won narrowly and the other of which he lost narrowly. In 2016, Hillary Clinton outraised Trump 2-to-1; she still went on to defeat in the battleground states.

We don’t have hard data on the effects of every aspect of presidential campaign spending — but one area with ample research into it is paid advertising, which just so happens to be the biggest expense for both Trump and Harris:

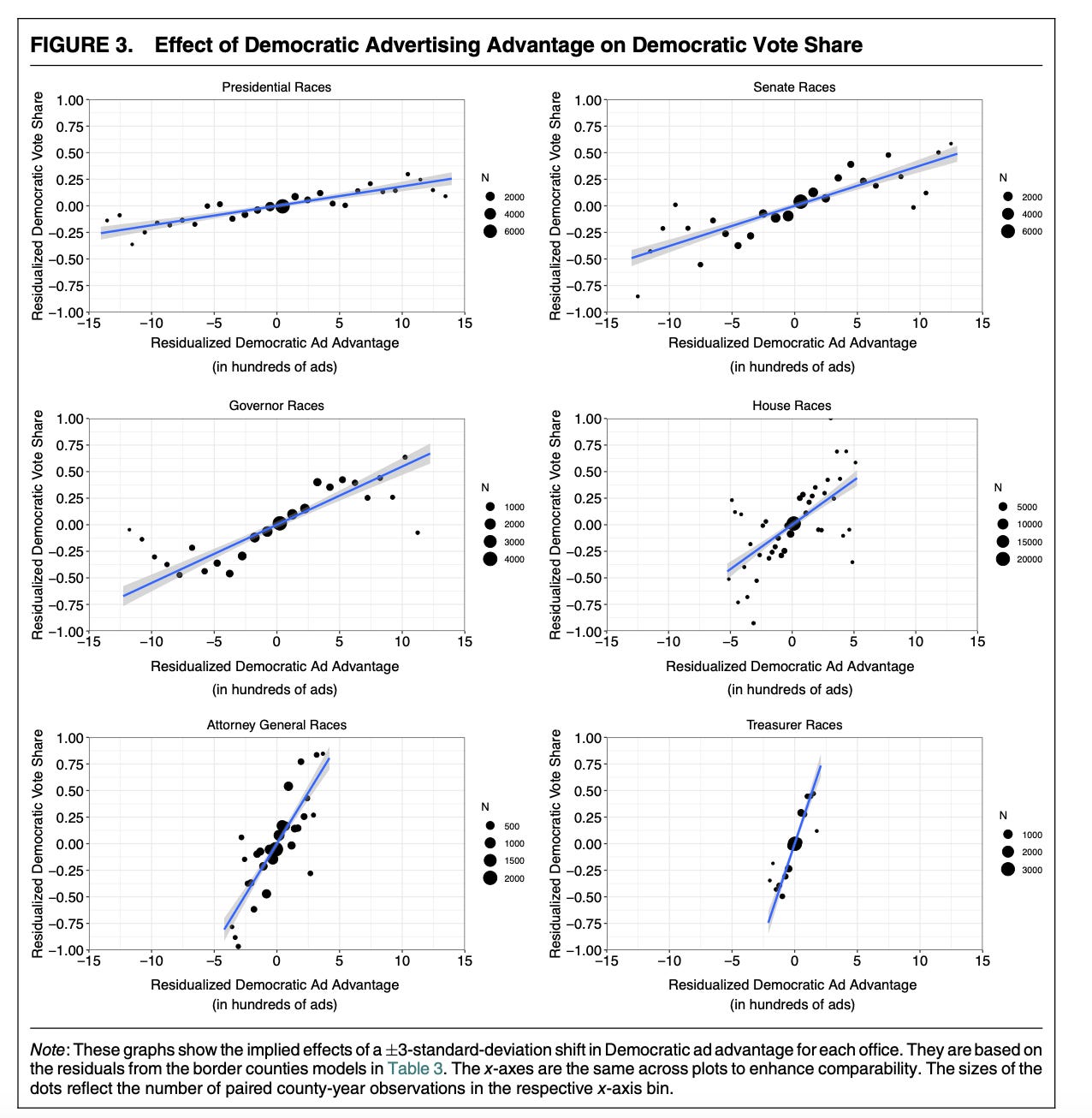

In a 2022 study, a trio of political scientists from Vanderbilt, UCLA, and GW examined television advertising in the five presidential elections between 2000 and 2016. By studying counties that sit alongside the borders of media markets, they found that a presidential candidate who airs 100 more ads than their opponent in a given county in the last two months of an election (adjusting for the county’s level of partisanship and other factors) can expect to increase their vote share in that county by about 0.018 percentage points. That isn’t nothing, of course, and in a tight race, every vote counts — but it does show that the effects of campaign spending is fairly muted. (Even the closest swing counties in American politics aren’t that close.)

“Overall, we found that TV ads didn’t change voters’ preferences for presidential candidates in presidential elections from 2000 to 2016,” one of the study’s author’s wrote. Since TV ads are the main expense that presidential campaigns plow their money into, that finding would suggest that a fundraising/spending advantage is far from decisive for a campaign.

But here’s where things get interesting.

From my standpoint, the most interesting expenditure by the Democratic Party in this election hasn’t been a drone show, and it’s hasn’t been a fleet of Philly-themed cars. It was this, from a DNC press release on Friday:

The Democratic National Committee is so flush with cash that, at this pivotal stage of a high-stakes presidential election, it’s sending money to the Democratic Party committees in all 57 U.S. states and territories. It’s the first time the party has ever done this.

That includes $400,000 to the state party in Florida, with the directive to focus on engaging the potentially critical bloc of Puerto Ricans who have recently moved to the state. $100,000 to the state party in Missouri, to spread some cash to the state’s abortion referendum in November. $70,000 to the state party in Idaho, not in hopes of winning any statewide or congressional seats there (it’s been years since Democrats have done that), or even in hopes of making major headway this cycle — but with the goal of breaking the Republican supermajority in the state legislature by 2030.

$70,000 may be chump change for a presidential campaign, but it can make a big difference in a state or local race, especially one that doesn’t see a lot of national cash— and that sort of long-term party-building can pay dividends for years to come.

The 2022 study I mentioned before also looked at this, studying 331 Senate elections, 226 gubernatorial elections, 3,859 House elections, and 237 other state-level elections between 2000 and 2018, again with an eye on TV spending. Campaign ads might not make a huge impact on the presidential race, but their effect on downballot races — where voters have much less defined views of the candidates — was considerably larger.

To be exact, the effect of an individual ad airing in a gubernatorial, House, or Senate election was two to four times larger than the effect of an ad airing in a presidential election. The effect of an individual ad airing in a state attorney general or treasurer race was 10 to 19 times larger than for a presidential ad. Suddenly, you’re talking about a sizable impact on a race.

That’s what happens when a presidential campaign has more money than it knows what to do with. The candidate’s party is freed up to cast its gaze downballot, where a single dollar can go a lot farther than it can on the presidential level. The RNC, which has been struggling financially, does not have this flexibility, but the DNC does — setting up a fascinating experiment in state-level investment rarely seen in a presidential year. The Democrats’ fundraising edge might not move things much in the Trump/Harris race, but the evidence suggests that these sorts of state-level money bombs very much could.

It’s worth noting here that some of the spending disparity can also potentially be explained by the fact that the Trump campaign is outsourcing much of its voter outreach efforts to super PACs and other outside groups — so there is more money in the Republican universe than just the Trump campaign data lets on.

But, as far as TV spending goes, outside groups have to pay a lot more to put ads on the air than campaigns do (since campaigns get a special rate). And the strategy comes with manifold other risks, some of which Politico reported on this morning in a piece about how worried many top Republicans are by the approach.

“Several Republican operatives said they aren’t seeing the same kind of presence either from the Trump campaign itself or from those outside groups that they did during his previous presidential runs, in 2016 and 2020,” the report reads. “Down-ballot candidates for state legislature in some battleground states aren’t running into Trump canvassers at the doors or seeing the campaign’s literature left behind the way they used to, they added.”

That big state party spend might be the best thing Democrats could ever do for themselves in the long term. I remember reading about how Obama in 2009 transformed his campaign into the group Organizing for America--only for so little of it to be turned into state party funds. One could even blame the Dems’ House losses in 2010 on that. It was the same issue with the Clinton campaign in 2016

I don’t think $400K is going to cut it in Florida, but ok. Rick Scott’s senate seat might actually be winnable. He’s never won by more than 1 point, and he’s concerned right now.

I wonder, did they gag and tie up Jen O’Malley in order to cough up some money for Florida? Sorry for sounding bitter, but I am bitter. I hold her accountable for single-handedly selling Florida out by focusing on the beloved rust states back in 2020, and now she was doing it again by announcing a few weeks ago that they don’t spend any money in Florida. Like they can’t walk & chew gum at the same time. (I mean, they can claim fighting climate change and handing out drilling leases like there’s no tomorrow, so, they clearly can do the walking/chewing thing when they want to.)

I hope they’re throwing everything they can at Osborn in Nebraska, Tester in Montana, the guy in Texas running against odious Ted Cruz, and of course Sherrod Brown and others. If we lose the senate, the Supreme Court will go completely ape shit crazy with yet another federalist wanker. Because, my favorite justice, beloved Sonia Sotomayor, is probably going to want to retire soon, and then what?