Congress Is Taking On the Housing Crisis. Finally.

Inside the room as Senate Banking advanced its first housing bill in over a decade.

American politics moves quickly in a micro sense (Did you see the latest report about Trump and Jeffrey Epstein?), but sometimes maddeningly slowly in a macro sense.

Year after year, even as society shifts and evolves in major ways, the political sphere continues to have the same debates over the same issues — immigration, guns, abortion, taxes — with only some minor shuffling of who’s saying what.

To be fair, when a big emergency erupts out of nowhere (a pandemic, or a recession, or a foreign war), Congress can and often does move swiftly to address it. But crises can also build over time, away from the spotlight. When they do, lawmakers will often neglect them, preferring to continue fighting in flashier (and more familiar) terrain.

The rise of social media is one such issue that Washington policymakers have been very slow to respond to. Another is the price of housing.

The U.S. is around four million housing units short, according to most analyses. With demand far outstripping supply, the median home price has skyrocketed almost 50% in the last five years. It is now at a record high.

You would be hard-pressed to find many Americans who aren’t aware of this issue (74% call it a “significant problem”), and yet it has been years since Congress advanced a major housing bill.

In fact, you could argue that housing is the issue with the largest gap between how much voters care about it and how little political attention it receives.

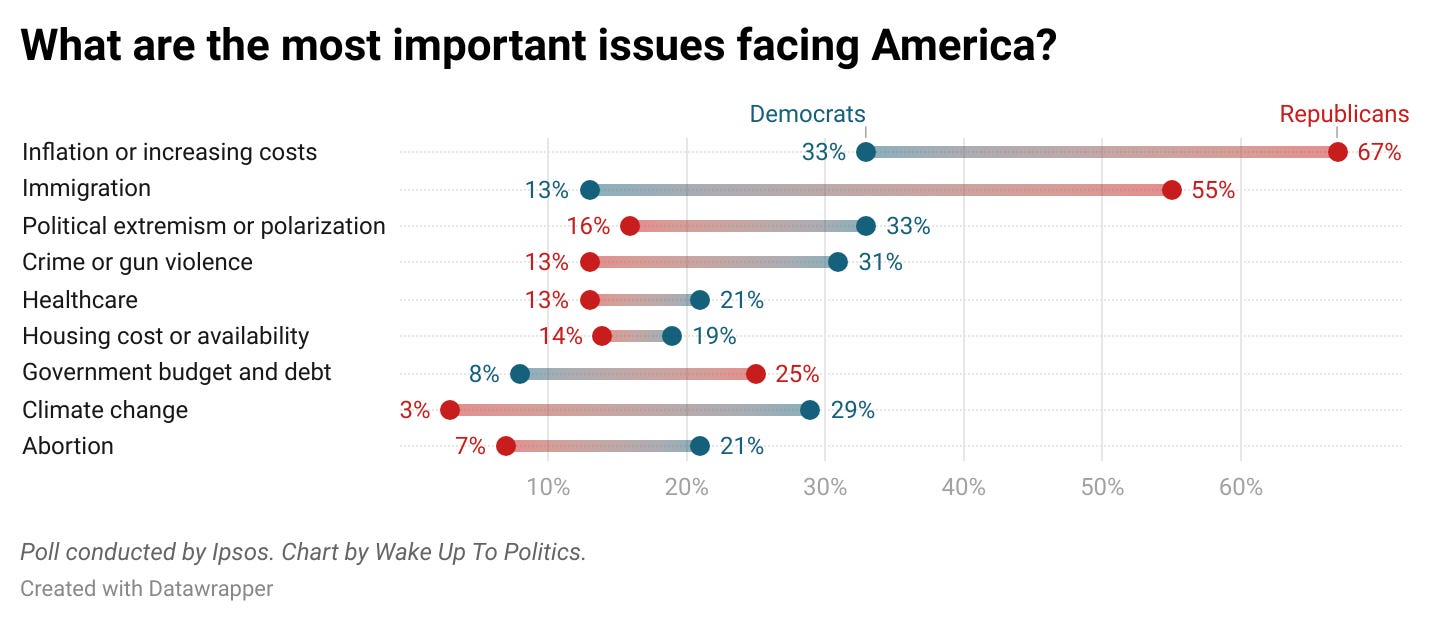

The below graphic shows the 10 issues Americans named as most important in an Ipsos poll last year (each respondent could pick three). For the most part, Democrats and Republicans hold wildly different views on the importance of each issue; housing stands out as the one with the closest levels of emphasis across the aisle.

It’s also the only one of these topics where partisan emotions don’t start running hot as soon as you bring it up. Unlike the other nine issues on the list, there isn’t really a well-known “Democratic” or “Republican” stance on housing. Perhaps as a result, it’s much less controversial, maybe even the least polarizing major issue in our politics right now. There’s no raging culture war attached. There aren’t years of back-and-forth to be mad about, or high-profile policies of the other side to bash. There’s agreement on the problem, and not much time spent hashing out a potential solution.

By that standard, in a functional Congress, it should be a perfect issue for Democratic and Republican lawmakers to roll up their sleeves and try to work on. On Tuesday, at long last, I headed over to Capitol Hill and watched a group of them do just that.

One of the Senate’s 16 standing committees quite literally has housing in the name — the Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee — and yet, it’s been more than a decade since the panel advanced a comprehensive housing package, even as the housing crisis has spiraled in that time.

That legislative drought ended on Tuesday, when the panel voted unanimously to approve the bipartisan ROAD to Housing Act. The 315-page legislation combines 28 separate proposals, most of which were written by bipartisan pairs of members on the Banking Committee. Every senator on the panel contributed ideas to the package, which was cobbled together by chairman Tim Scott (R-SC) and ranking member Elizabeth Warren (D-MA).

As a result, it would try to tackle housing from a broad range of angles.

From Sens. Warren and John Kennedy (R-LA), there’s a provision that would reward cities with better housing track records, pegging the housing grants a jurisdiction receives to how many homes they’ve been able to build.

Sens. Mike Crapo (R-ID) and Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-DE) contributed a mandate for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to develop a set of “best practices” frameworks for zoning and land-use policies, encouraging states and cities to remove common obstacles to building new homes.

The package includes a proposal to streamline the federal environmental review process to speed up housing projects funded by HUD, written by Sens. Mike Rounds (R-SD) and Andy Kim (D-NJ), and another that would do the same for rural housing projects, courtesy of Sens. Jerry Moran (R-KS) and Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH).

Four separate provisions would aim to boost housing for veterans. Another would try to reduce appraisal bias. There’s a section of the bill dedicated to getting more housing build near public transportation routes. And there’s a new grant program to turn abandoned or run-down buildings into new single- and multi-family homes.

Also, the bill would create the first federal grant program to help fund home repairs, a $1 billion innovation fund that will support communities that are modifying their land-use rules to build more housing, and eliminate the chassis rule, which Vox recently called an “almost absurdly simple fix that could help ease the housing crisis.” (A 50-year-old law requires manufactured homes to be built on a “permanent chassis,” a foundational structure attached to wheels, which experts say does not make the homes safer but does make them more expensive to produce.)

“A lot of good ideas made it into this bill,” Warren told me at the Capitol on Tuesday. “It makes it hard to describe a single thing that this bill does.” But, she added, it also means that a lot of lawmakers have buy-in to the legislation: “It makes it a bill that a lot of policymakers can look at and see help in their home communities. I may look at one piece because I’m representing Massachusetts, while my chairman thinks about this other part that’s really gonna be good in South Carolina.”

When I arrived at the Banking Committee meeting Tuesday morning, I was prepared for it to stretch on for hours, as sessions of this kind often do. Instead, the meeting was over in a crisp 55 minutes. Only one member, Sen. Cindy Lummis (R-WY), offered an amendment (about taking crypto assets into account when assessing mortgage eligibility) but promptly withdrew it, saying she only brought it up to “plant a seed” for future conversations.

When it came time to call the roll, the clerk recorded 24 ayes and zero nays. “Can you say that one more time?” Scott asked in mock astonishment.

“For far too long, Congress believed this problem was too big to solve,” Scott said during his remarks. “Today, we’re taking not a step, but a leap, in the right direction in a bipartisan fashion. Many people around the country frustrated with the way we do American politics wonder, ‘Is there any issue that brings this nation together?’ And I’m here to say, ‘Hallelujah, we have found one!’ It is housing.”

I went to the Banking Committee meeting partially because I wanted to see what congressional bipartisanship looked like in Donald Trump’s second term.

And I can report, at least inside the committee room, the vibes were very friendly.

Scott and Warren, two former presidential candidates, grinned and thanked each other profusely for their hard work on the package. Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) ribbed Sen. John Kennedy (R-LA) for “subtly” creeping away from federalism by sponsoring a proposal that would urge states and cities towards more housing. Scott turned across the aisle to Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA), a pastor, as he exulted in the 24-0 vote. “Let us pray. Will you lead us Reverend Warnock?” Scott joked.

“Praise the Lord!” Warnock responded.

“It’s a good day for America,” Scott said, expressing pride that each of the committee members “looked for a product that could become a law” instead of grandstanding.

Outside the auspices of the Banking Committee, however, both parties are wrestling with whether to work across the aisle.

On the Republican side, the White House is pushing for an end to the bipartisan appropriations process and trying to chip away at one of the last remaining bipartisan checks on nominations. The co-chairs of the House Problem Solvers Caucus recently requested a meeting with President Trump to discuss bipartisan solutions on immigration, permitting reform, and the national debt. Based on Trump’s disinterest in bipartisan lawmaking thus far, they shouldn’t hold their breath.

Meanwhile, Democrats are split on whether to work with a Trump administration they view as trampling on laws and norms, a feud that broke out into the open on the Senate floor yesterday. “This, to me, is the problem with Democrats in America right now,” Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) said, pushing back on his co-partisans who were trying to secure unanimous consent for a bipartisan package of police funds. “We’re willing to be complicit with Donald Trump to let this pass through, when we have all the leverage right now there is.”

“I’m not sure the answer here is to stop bipartisan legislation that gives tools to law enforcement across the community to keep our communities safe,” Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) responded.

The housing bill offers an interesting test of whether Congress can still work together in a fractured era. It is unclear whether Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) plans to bring it to a vote, although Sen. Kennedy (R-LA) said Tuesday that he plans to chase Thune “like a dog to the treeline” to urge him to do so.

The only real polarizing moment at Tuesday’s meeting came when Sen. Bernie Moreno (R-OH) opted not to speak about the housing bill directly during his remarks, instead criticizing Democrats for holding up so many of Trump’s nominees, requiring additional procedural votes that eat up floor time. “Maybe we don’t need to do that for every nominee,” Moreno said. “If there’s a chance to get these nominees confirmed in larger numbers that are not so controversial, I would urge my Democrat colleagues to do that so we can clear floor time to get bills like this.”

Warren, who made a point of nodding along vigorously as the other Republican senators spoke about the bill, sat stone-faced during Moreno’s remarks. This is Washington, after all: the Hallelujah chorus never lasts for very long.

They are two different issues, Gabe. Let's not give Moreno a gold star and gatekeep Warren's facial expressions. He's the one that made it polarizing.

If Moreno want to bring a worthwhile bill to the floor he can. He didn't need to whine about nominations that were held up because the candidates were horrendous. Moreno does not care about our lives in Ohio unless it's about transgenderism and he can trample on them more. No matter how controversial, this man will vote for whatever Trump tells him to vote for. Moreno would hold up nominations if it was a Democrat.

Thanks, a refreshing look at Congress for once! Too bad we can’t see it more often.