Congress is Finally Doing Its Job. Nobody Seems to Notice.

Compromise is not a last art in Washington.

Good afternoon! It’s January 15, 2026. President Trump is threatening to invoke the Insurrection Act in Minnesota. Trump beat back a Senate effort to restrict his war powers, persuading Republicans Josh Hawley (MO) and Todd Young (IN) to flip their votes. And the president is set to meet today with Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado.

But this morning we’re heading over to the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, to let you in on an under-covered story of bipartisan success.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the years writing that, while it’s true Congress could be getting a lot more done, our lawmakers are still underestimated for how much they do achieve, at least relative to their popular image (an admittedly low bar).

So it’s time for me to admit something: I recently did what I accuse everyone else of. I underestimated Congress. And this week, they (at least partially) proved me wrong.

Let’s back up. Congress’ main job each year — the one thing it must do, even if it does nothing else — is funding the government. As we have discussed before, they do this by passing 12 annual appropriations bills (split into categories like “Defense,” “Labor/HHS/Education,” “Transportation/HUD,” and so on), which codify government funding levels for the subsequent fiscal year.

In theory, they are supposed to have this done by each October 1, the start of the fiscal year. In reality, the task basically always stretches into the new fiscal year (and, then, often the new calendar year as well). Congress passes continuing resolutions (CRs), extending funding at the levels set in the last fiscal year, to plug the gaps, or else the government shuts down.

Of course, this is exactly what happened at the beginning of this fiscal year, FY2026. October 1, 2025, rolled around and Congress hadn’t passed a single appropriations bill into law, nor could the two parties agree on a CR. The impasse continued for 43 days, the longest government shutdown in history. Hardly an auspicious way to ring in the fiscal new year!

At the time, I noted that — behind the scenes — the bipartisan appropriations process had actually been proceeding along fairly well, which made the shutdown dispute all that much stranger. But I expected the shutdown to throw a wrench into all of that, maybe irreparably.

By November, House Appropriations Committee chairman Tom Cole (R-OK) was floating the idea of a full-year CR for the remaining appropriations bills, the congressional equivalent of throwing in the towel. Keep in mind that all 12 appropriations bills were already funded by a full-year CR in FY2025. An additional full-year CR would have meant that funding levels set in the spring of 2024 would have persisted all the way until October 2026, with almost no edits to account for anything that had changed in the outside world since then. What business would budget that way?

This would have meant (as the White House seemed to hope) the death of the bipartisan appropriations process, showing that there was simply no way for Democrats and Republicans to agree on budgets anymore. By December, I was presenting this to you as a very real possibility.

But then: bipartisanship was suddenly resurrected, like a phoenix rising out of the shutdown’s ashes. As of two weeks ago, only three appropriations bills had been enacted (as part of a package that ended the shutdown). Within days, that number is poised to shoot up to eight.

Of course, real challenges remain: eight isn’t 12. But it’s worth taking a moment to recognize that Congress is actually doing its job after months of delay, with huge bipartisan majorities coalescing behind bills that fully embody that thought-to-be-lost Washington art: compromise.

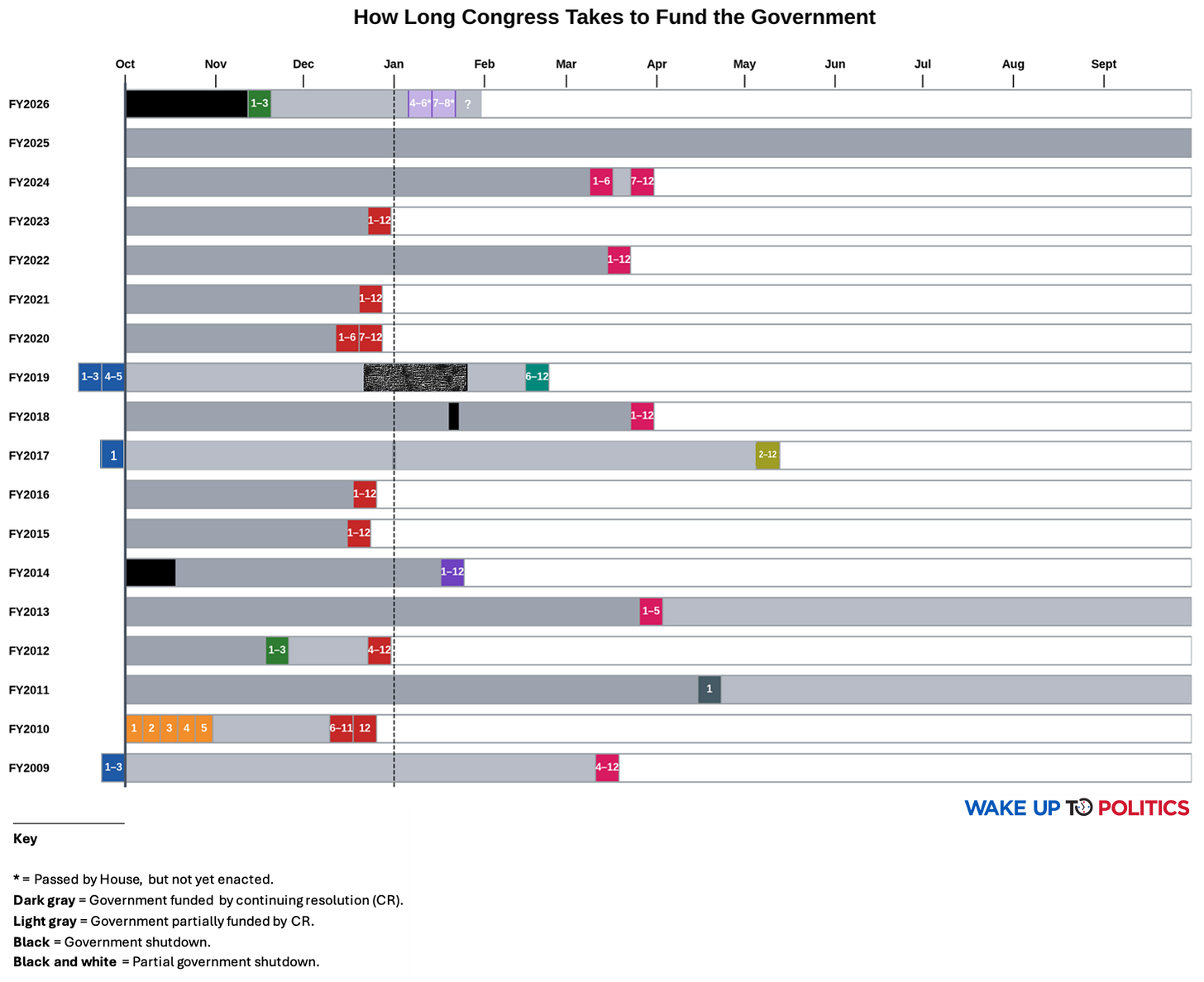

The chart below shows the pace of the appropriations process under the last four presidencies. Each colored box represents a package of bills, so if all 12 appropriations bills were passed together, it’s labeled “1-12.” If they were approved in two tranches, the boxes are labeled “1-6” and “7-12.” And so on. (If the government was instead funded by CR or shut down, it’s noted with gray and black bars, respectively.)

This chart lets you see how long it takes for lawmakers to “get to 12,” if you will. (Theoretically, they’re supposed to be there by the start of October, but as you can see, they rarely get even a handful of appropriations bills passed by then, much less all 12.)

“This is the most progress that has been made on appropriations in years,” Senate Appropriations Committee chair Susan Collins (R-ME) told reporters this week. “So I am delighted.” That isn’t quite true, as you can see: Congress moved faster than this in FYs 2020, 2021, and 2023. But this certainly does beat most of the appropriations processes of the Trump I and Biden years — and several of the Obama years as well.

Ultimately, the speed of the FY2026 process lands about in the middle of the pack out of the years reflected above. But considering where the fiscal year started (with a historic government shutdown), and the poisonous partisan tensions that threatened to derail the process entirely: middle of the pack ain’t bad.

The dirty secret of government spending bills is that they always require bipartisan support, since the 60-vote Senate filibuster ensures that spending bills can’t pass without cross-party buy-in. That threshold is sometimes so hard to reach that the process collapses (as in FY 2025). And sometimes it frustrates both parties so much that they muse about getting rid of the filibuster when they’re in the majority.

But that might be shortsighted: the supermajority threshold is the only reason parties get a say in the appropriations bills when they’re in the minority, ensuring that a simple majority can’t just ram through partisan bills that defund the minority’s goals whenever they’re in charge, and that the other party can’t then do it back to them once power shifts.1 It ensures stability, so that overall funding levels don’t vary that much depending on who boasts a slim congressional majority (much to the consternation of partisans on both sides). And when the process does work, it means that the appropriations bills are a product of classic give-and-take compromise.

Let’s look at the most recent examples.

Last week, the House voted 397-28 to pass the Commerce/Justice/Science, Energy/Water Development, and Interior/Environment appropriations bills. The Senate advanced the package 85-14 this morning and is expected to approve it soon. Last night, the House voted 341-79 to pass the Financial Services/General Government and State/National Security bills, which are also expected to advance through the Senate easily.

Take the State/National Security measure, for instance. Republicans boasted that the package (which funds America’s foreign aid efforts) shrank by $9.3 billion (a 16% cut) compared to last year. Democrats, meanwhile, bragged that the measure was still $19 billion larger than what President Trump had asked for.

Republicans cheered the creation of an “America First Opportunity Fund,” which Trump had requested as a flexible account that could be used at the Secretary of State’s whim. Democrats noted that the account was only $850 million (compared to the $2.9 billion Trump had requested), and would include more restrictions than the president intended.

Democrats were able to say that the U.S. Agency for Global Media (which includes Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and Radio Free Asia, and which Trump has tried to defund) was, in fact, funded to the tune of $643 million, not $0. Republicans highlighted that the bill includes upwards of $2 billion aimed at countering China, and $150 million to combat the flow of fentanyl.

Democrats noted that the bill does not zero out funding for the United Nations, as Trump requested. Republicans highlighted that it does require the State Department to take into account a country’s UN voting record when allocating foreign aid.

Give, and take. Give, and take. That’s what it means to compromise.

This story can be repeated for all five appropriations bills that have zoomed through the House (in two packages) with striking support and speed in the last two weeks. Republicans like that the Financial Services/General Government bill cuts the IRS by 9%. Democrats are happy that it ensures the local budget for Washington, D.C. can’t be slashed in the middle of the year again, as happened last year. The Commerce/Justice/Science bill rejects Trump’s proposed research cuts almost across the board; at the same time, it includes an 18% boost for the U.S. Trade Representative, which Trump had wanted in order to staff his ongoing tariff work and trade negotiations.

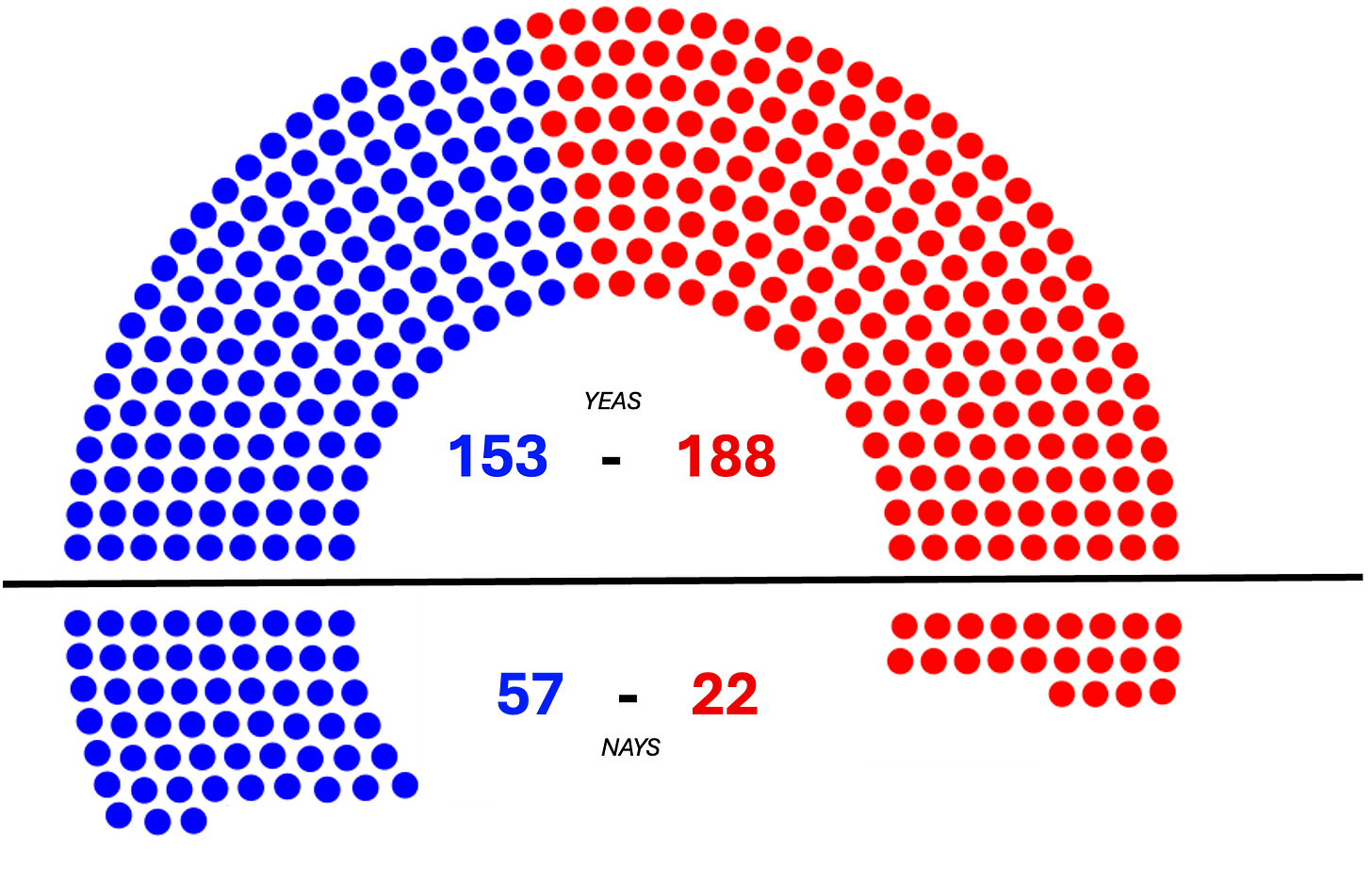

The State/National Security vote, which took place in the House yesterday, was what you might call a classic “horseshoe vote.” 188 Republicans and 153 Democrats supported the measure; 22 Republicans and 57 Democrats opposed it. The wings of both parties had their issues with the bill, but the members in the middle all supported it.

There were also two amendment votes on proposals by conservatives: one by Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX) to eliminate the salaries of two district judges who have earned the ire of the president, and another by Rep. Eli Crane (R-AZ) to eliminate the National Endowment for Democracy, an agency despised by Elon Musk which Trump had sought to defund but which is given $315 million in the package.

Both amendments were defeated by bipartisan majorities: 257-163, and 291-127, respectively.

“Is it perfect? Is it everything you want?” Cole said in a committee meeting this week. “No. But this is about running the government on a day-to-day basis.” (Cole also noted that “if you’re worried about the power of Congress versus the power of the executive branch, the best way to assert the power of Congress is to pass appropriations bills,” since “CRs increase the power of the executive branch” and give the president more flexibility in spending money. Indeed, appropriations bills include more detailed instructions restricting presidential control of spending compared to CRs, which were all that were in place for most of Trump’s first year — and these appropriations bills include more guardrails than most, a direct response to Trump.)

As I’ve written before, the “planes that land” rarely receive coverage in Congress, which is a shame — because it leaves Americans with a skewed image of their representatives. A shutdown is a surefire way to get wall-to-wall news, but scan the front pages of the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal this morning and you won’t see anything about the bipartisan appropriations bills that are now quietly making their way through Congress, the mirror image of last year’s partisan funding clash.

That doesn’t mean a shutdown isn’t a worthy topic of coverage, too: of course it is. But surely so is the fact that lawmakers have managed to agree on a slew of big funding packages across party lines? If Americans hear about the lack of a funding deal ad nauseam, there’s no reason to deprive them of knowing what’s in the eventual funding deal as well. We’re the ones footing the bill after all.

If the Senate approves the House-passed funding bills and President Trump signs them, we’ll be up to eight FY2026 appropriations bills becoming law. That still leaves four that need to be approved by the time the current CR expires on January 30.

And because I try to be honest with you in both directions — writing about when Congress is getting things done and when they aren’t — it’s important to note: these last four bills are likely to be a lot more complicated than the other eight.

The quartet that remains: Transportation/HUD, Labor/HHS/Education, Defense, and Homeland Security.

Of these, Homeland Security is emerging as the biggest sticking point, as has repeatedly been the case in the Trump era. After an ICE officer fatally shot Renee Good in Minneapolis last week, a growing number of Democrats are saying they will oppose a Homeland Security appropriations bill unless it includes some ICE reforms.

Talks are still ongoing: per Politico, Republicans have made an offer to Democrats to include a provision requiring ICE to purchase body cameras for their agents, in exchange for Democrats backing the measure. But it’s unclear if a deal will be reached. “Right now, there’s no bipartisan path forward for the Department of Homeland Security,” House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries told reporters yesterday.

Theoretically, this could end with a DHS-only shutdown if Democrats choose to force one, or potentially with the agency being funded by a full-year CR. (Sidenote: even if the two sides agree to a CR, allowing ICE to keep its current funding levels intact but declining to give it a boost, this does raise the prospect of what this fight will look like next year if Democrats win back the House. It’s hard to imagine Democrats placing a bill on the House floor that doesn’t meaningfully alter ICE. And it’s equally hard to imagine the Trump administration ever accepting any changes. Set your watches for 2027: this seems like a perfect recipe for a shutdown next year, even if one is avoided now.)

So, dangers certainly lie ahead, and I will report on them as they come up. But, for now, it’s worth noting the fact that Congress pulled the appropriations process from the dead — achieving “something of a miracle,” as a CNN reporter put it. (The Appropriations Committees, which hashed out these deals across party lines, are “literally saving Congress,” the reporter said one lawmaker told her.)

The demise of bipartisan compromises — where not everyone is thrilled, but enough people are satisfied — seems to have been greatly exaggerated.

As always, it’s important to note that appropriations bills only touch discretionary government spending. Somewhat paradoxically, mandatory government spending — which includes spending on entitlement programs — can be increased or decreased by only 51 votes through the reconciliation process, as Democrats did with the Inflation Reduction Act and Republicans did with the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. (The parties can also create new pots of mandatory spending through this process, allowing them to make changes that would normally require 60 votes with only 51.)

Super helpful, as always.

Thank you as always for balanced reporting!