A Unified Theory of the Last 24 Hours

Donald Trump has failed to break the most predictable cycle in politics. Will Democrats?

Some days, it’s difficult to find anything to lead the newsletter with. Other days, there’s so much news that it’s difficult to choose. (The latter has been much more common lately.) Today, there are at least four stories that could be full newsletters all on their own:

Democrats won a key election to maintain control of the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The party also overperformed in a pair of Florida special elections.

It’s “Liberation Day”! President Trump is set to unveil a new, sweeping slate of tariffs at the White House this afternoon.

Republicans continue to lack unity in Congress, struggling to forge consensus on a reconciliation package and dealing a notable defeat to House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA).

Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) delivered a 25-hour stemwinder against the Trump agenda, breaking the record for longest Senate floor speech set by Strom Thurmond as he tried to block civil rights legislation in 1957.

A lesser newsletter might pick just one of these stories, or tackle them individually. Not Wake Up To Politics! Let’s talk about all four at once.

Washington Post columnist Shadi Hamid recently wrote that he had been wrong about something:

For a moment, it seemed like anything was possible. With Donald Trump’s popular-vote victory in November, the old order had been dealt a devastating blow. Democrats were mostly despondent. The resistance had petered out. Where to go from here? No one really knew.

Many observers of American politics, me included, thought that a new era had begun — one of Trumpian hegemony. Republicans, emboldened, would reshape American culture, ushering in a period of conservative dominance for years, if not decades. This was the “vibe.” In theory, cutting waste and making the federal government more accountable were popular ideas. For a majority of Americans, progressive policies on issues such as immigration and transgender rights had run their course. Trump was riding a wave of exhaustion with Democrats’ cultural overreach.

But, then, the realization:

I was wrong to think that this — whatever this was — would be more lasting. It wasn’t. It turns out the moment of Trumpian dominance was just that: a moment. Something has shifted again. We are now in another phase: the vibe shift away from the vibe shift.

It is admirable for Hamid to acknowledge that he got something wrong, and all of us who write in public should do so more often. (I myself have made more than a few false predictions in 10+ years of newslettering!) But I also think, in this case, this was a very easy pattern to see coming, even with only a few decades of historical hindsight.

Twenty years before Donald Trump won the presidency with 49.8% of the popular vote, George W. Bush won it in 2004 with 50.7% of the vote. The Bush team famously declared that they had won a broad “mandate” to govern, and went about promoting a plan to partially privatize Social Security. The proposal was massively unpopular; by 2006, Bush’s “mandate” had given way to Democrats majorities in both the House and Senate.

Two years later, Barack Obama won the White House in 2008 with 365 electoral votes, a seven-point advantage in the popular vote, and a 59 (soon 60)-seat majority in the Senate. Progressives were sure that the “emerging Democratic majority” had arrived, and it was probably the moment in the modern era that it was most defensible for either party to believe so. But Obama, too, went about pushing an unpopular change to government benefits, and his party was shellacked — his words — in the 2010 midterms, losing 63 seats to the Republicans.

But you don’t even have to reach back twenty, or sixteen, years to see this familiar cycle unfold. How about 2020, when Joe Biden announced that his presidency would be “FDR-sized,” even though he was lacking an FDR-sized presidential victory or congressional majorities? This one you probably remember: Biden pursued a progressive policy agenda that lacked popular buy-in, helped fuel inflation, and ultimately led to his arch-rival-slash-predecessor becoming his arch-rival-slash-successor.

All of the presidents in the modern era who claimed to have built permanent majorities ended up having two- or four-year majorities, at best. Hamid is right that Trump had an opportunity to break this cycle when he was elected: his victory may have been slim, but it showed signs of reaching into new demographics that — if he were to focus his presidency with them in mind — could have expanded the GOP into the type of party that wins elections not just 50/50, but maybe 55/45 or even 60/40. Democrats, as Hamid noted, were also sufficiently demoralized that they felt they needed to moderate and work with him, which could have allowed him to cow them into passing a popular policy agenda that would have been approved under his name. (I wrote here about what such an agenda might have looked like.)

But anyone who thought that Donald Trump would organize his presidency in this way does not know Donald Trump. One week after the election, I wrote:

A dirty little secret is that Americans don’t like dramatic policy changes and, despite the fact that they often send politicians to Washington demanding such change, voters usually get frustrated with them pretty quickly when they try to deliver it. In short: voters hate the status quo — until someone tries to change it, and suddenly they hate the new status quo even more.

…In all likelihood, this same pattern will repeat itself with Trump. Most experts agree that both mass deportations and universal tariffs would have adverse economic consequences, including exacerbating inflation (which, as we learned anew this cycle, voters are particularly sensitive to). If the president-elect succeeds in carrying out these and other proposals, it will likely spark voter backlash and allow Democrats to win a House majority in 2026. Suddenly, a party now in the wilderness will have its foot in the door; the fluke circumstances that helped contribute to their losses (Biden’s age and unpopularity; global frustrations about Covid-era inflation; a rushed nomination process) will melt away and be replaced by new fluke circumstances that will likely hurt Republicans.

In that lens, let’s start marching through our news items of the day. #1 (the elections in Wisconsin and Florida) is evidence that the voter backlash to Trump is already forming, that his policies so far have failed to either keep his own voters unusually engaged or to win over an unusual amount of the opposition party’s voters.

In Wisconsin, a state Trump narrowly won in 2024, a liberal Supreme Court candidate won by 10 percentage points. In Florida, a pair of districts that went for Trump by 37 and 30 points each elected House Republicans by 14 points. Trump’s first 70 days have failed to conquer the beast that is thermostatic public opinion.

If I had to guess, #2 (the tariffs) will become the seeds of even further backlash. It’s unclear exactly how broad today’s “liberation” will be; per CNBC, as of yesterday morning, Trump administration officials were still debating three different tariff strategies. But part of the reason this has sparked so much internal deliberation is that Republicans are terrified that the tariffs will raise prices and prove politically toxic.

With good reason. Per a CBS News poll, 55% of Americans say Trump is focused “too much” on tariffs; 64% say he is focused “not enough” on lowering prices (one of his key campaign promises).

All of this also helps explain #3 (Republican inability to unite behind a legislative agenda). As I’ve written, Republicans have yet to forge agreement on nearly every aspect of their reconciliation package, which will be the signature legislative push of Trump’s first year. Later today, they are expected to release a budget resolution (the first step in the reconciliation process) that will sidestep most of these debates, pushing them off until further in the process.

That’s fine; it will get them through the week, and let the party “survive and advance,” as is reportedly the strategy of Republican leadership. But these disagreements will have to be settled eventually — and if Donald Trump’s popularity continues to drop, it will only become harder.

The further down his approval ratings slide — and the more election results like Tuesday’s that emerge — the more nervous vulnerable House Republicans will get about a package that is likely to cut Medicaid and pad the federal deficit. Already, there are interesting cracks in the GOP wall of support for Trump, likely born out of fear of electoral backlash to his policies.

In the Senate, Appropriations Committee chair Susan Collins (R-ME) joined a bipartisan letter to bash Trump on some of his spending decisions last week; Health Committee chair Bill Cassidy (R-LA) joined a bipartisan letter asking Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to testify in light of widespread cuts in his department.

In the House, eight Republicans penned a letter to Trump on Tuesday asking him to “reconsider” his executive order ending collective bargaining at many federal agencies. Notably, several of the GOP lawmakers tweeted out that they had done so, which is unusual for Republicans disagreeing with the president. Here’s Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA):

And here’s Rep. Mike Lawler (R-NY):

Both congressmen won districts that Kamala Harris won by a single percentage point in 2024. You only get tweets like that if they are scared that Trump’s actions will make it harder, not easier, for them to win re-election next November.

Ironically, during the campaign, Republicans — with some success! — targeted union voters, historically a Democratic constituency. But the order Fitzpatrick and Lawler are objecting to is exactly the type of action you’d enact if you are not interested in cementing these gains long-term.

Trump, with the tariffs especially, almost seems as though he wants to lose the support of voter groups he overperformed with in 2024 (largely because they wanted prices to be lower). If so, it’s working. In January, 36% of non-white voters approved of Trump, per Gallup. That’s slid to 27% by March. He’s down four points among voters under 35; down 11 points among independents.

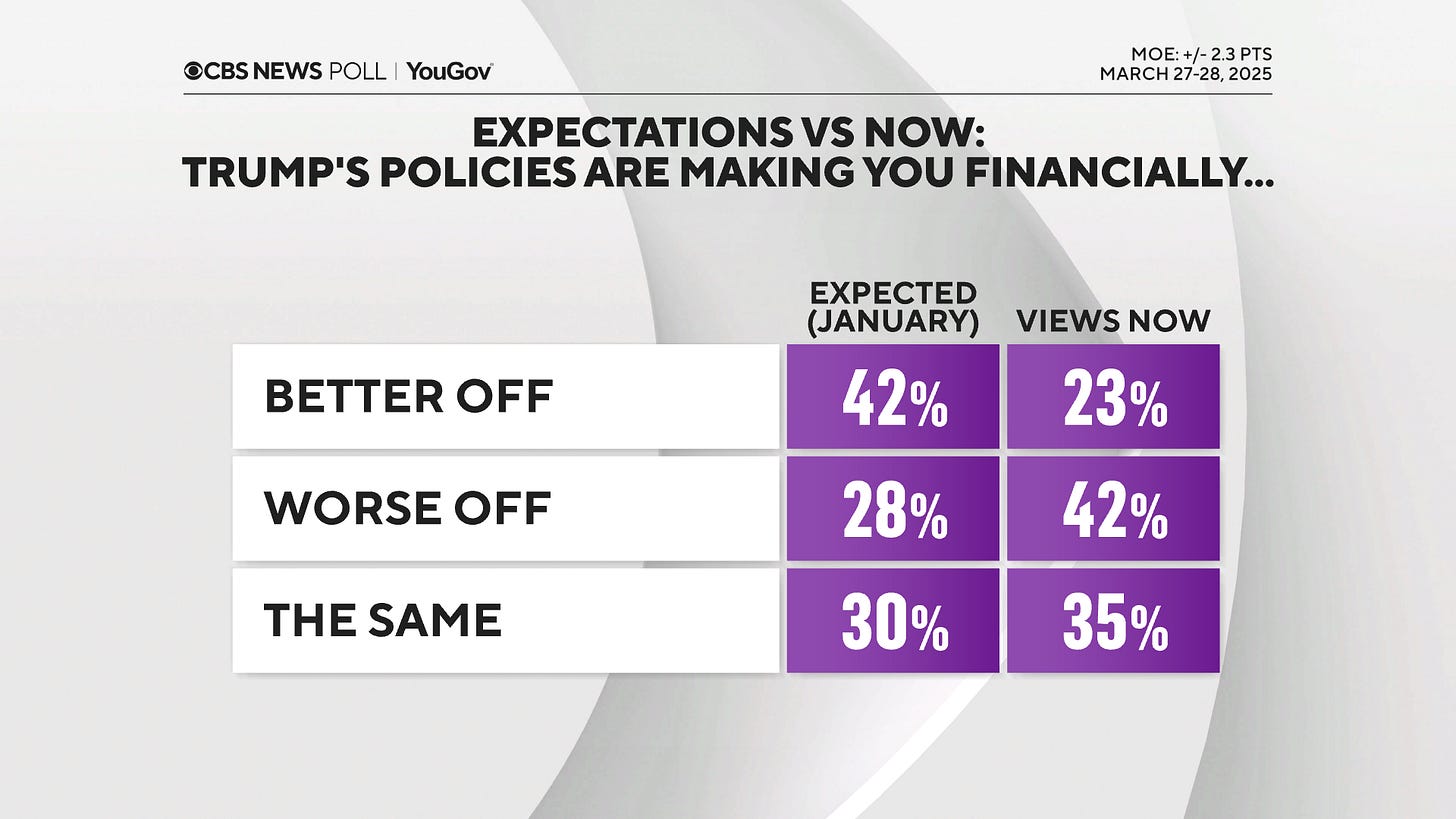

Per a CBS poll, 42% of voters in January thought Trump would make them better off financially. Today, that number has plummeted to 23%.

Not everything Trump has done is unpopular. The deportations are popular, although they run the risk of overreaching. An executive order he signed Monday to target price-gouging for concert tickets would probably be popular — that is, if anyone heard about it. The problem with a “flood the zone” strategy is that it carries with it a presumption that everything you’re doing will be unpopular (why else do you want to hide it?) But that means that when you do pursue popular proposals, they will get lost in the shuffle, because of your own strategy to overwhelm and prevent individual initiatives from cutting through.

By doing so, Trump has burned — impressively quickly — through the goodwill he built among voters he made inroads with in 2024. And he’s likely lost the chance to turn Republican gains into a durable Republican majority.

And so that brings us to #4 (Booker’s speech). Trump, like Bush, Obama, and Biden before him, had the opportunity to realign American politics behind a popular agenda. Like his predecessors, he chose not to. Instead, he picked Elon Musk and tariffs, helping lead to electoral backlashes like those we saw last night.

Thus, the next party who will have a chance to craft a broader-based coalition — to try to win a 55-45 election for once, rather than playing to their base and trying to squeak by 50-50 — is the Democrats.

Yesterday, Booker’s marathon address gave us the best insight into how (or whether) the party is trying to do so. From a physical standpoint, the feat was obviously impressive. (Booker told reporters that he stopped eating on Friday and stopped drinking on Sunday, in order to be able to stand for 25 hours without going to the bathroom.) From a historical standpoint, it was also a clear symbolic victory: one of the Senate’s few Black members wiping away a record held by one of the chamber’s most notorious segregationists.

From a political standpoint, the jury is still out.

I can’t claim to have watched all 25 hours of Booker’s address, but the parts I watched didn’t necessarily seem to cohere into a governing vision that could win over a durable majority. Of course, it didn’t have to. My guess is the purpose of the speech wasn’t to do that, it was to energize the Democratic base (and to push Booker into conversations about the 2028 primaries). Booker’s speech and the Wisconsin results seem to have accomplished that.

“What a strange feeling... is that... joy?” the progressive commentator Charlotte Clymer wrote on Tuesday night. Here’s a former Kamala Harris adviser summed it up:

Mission accomplished, then. But I was struck by the fact that Booker didn’t even seem to be trying to reach into voter groups who don’t already agree with him. After the speech, as far as I can tell, Booker gave three interviews: one to MNSBC mainstay Rachel Maddow, and one each to liberal influencers Jack Cocchiarella and Aaron Parnas.

This is part of Democrats’ efforts to reach influencers after Trump catered the group in 2024 — but they confuse the medium with the audience. What Trump did in 2024 was reach out to influencers with heterodox political views and mixed political audiences. (Half of Joe Rogan listeners didn’t vote for Trump in 2020, according to one survey. Rogan himself is a former Bernie Sanders supporter.) Focusing on influencers, but only those who will reach people who already agree with you anyways, misses the point.

After an attention-grabbing moment, why not go on Fox News — the country’s most-watched cable news channel — to press your case to independents? Or sit for interviews with a few influencers or podcasters from outside the Democratic bubble?

Booker’s choice of interviewers isn’t, on its own, a signal that Democrats will make Trump’s same mistake — catering inside the tent rather than reaching outside of it — but it certainly isn’t a signal of planning to do the opposite. Winning the Wisconsin election, while similarly energizing to the base, is also not a signal that the party has expanded its coalition.

Because of the nature of off-year electorates, the GOP’s failure to win the Wisconsin seat can’t be read as a barometer for the whole country, but it can be seen as a sign that Trump’s second-term activities have failed to win over the demographics that oppose him (highly engaged, well educated voters). But, by the same token, the Democrats winning the seat is only evidence that they have kept those voters in their tent, not that they have reached beyond it. Democrats would be wrong to over-interpret these and other results (as they did after the 2022 midterms, as Trump is doing now) as a broader embrace of their agenda.

For example, the anti-Trump newsletter The Bulwark declared this morning:

Yesterday’s high turnout also suggests that voters can grasp that courts matter, and that the rule of law matters. It was a judicial election, so the issue of economics wasn’t central to the debate. But it turns out families talk about more at the kitchen table than the price of groceries. They talk about what kind of state, and what kind of nation, they want to live in. Democrats shouldn’t shy away from raising issues of basic justice and fairness and individual rights.

Um, maybe. Obviously, some voters care about those issues more than the price of groceries. But yesterday’s electorate was composed disproportionately of Harris voters, unlike the overall Wisconsin electorate, which elected Trump. So the outcome should not be taken as evidence that non-Democratic voters are especially motivated by these issues. Booker’s speech, similarly, was largely framed around a “moral moment” for the country. The Washington Post’s Perry Bacon described it as a “bold statement that Trump is destroying institutions.”

But evidence is still lacking that voters will rally behind a message about “moral moments” and institutions. In a Blue Rose Research survey last year, asked whether “preserving America’s institutions” or “delivering change that improves Americans’ lives” is more important, 78% of respondents chose change. 18% chose institutions.

So where does that leave us? Trump appears to have squandered the opportunity to appeal to a broad-based coalition of voters. Democrats don’t yet seem positioned to form one.

One line of thinking is that neither party should be focused on doing this at all. Maybe the country is too moody, too indecisive, that there is no point trying to form a durable majority. Maybe our politics are too poisoned by cultural divides to craft a “big tent.”1 Better to get into office and move as aggressively as possible, even if it means losing control of government in just two years.

I recently read the book “Realigners,” by George Washington University professor Timothy Shenk, which imagines a different path — or, at least, recounts the era in which a different path was taken. He calls the book a “biography of American democracy told through its majorities, and the people who made them.”

“There are plenty of visionary proposals out there for remaking society,” Shenk notes. “What’s missing is a plan for building a coalition that could turn those dreams into reality.” He writes about people throughout history who tried to plan these sorts of realignments, ranging from Martin Van Buren to Phyllis Schlafly.

“At their most effective,” he writes, “realigners combine a brutally frank assessment of the political system with a vision for how they might still change the country. Rejecting the moderate’s dream of unanimity, they accept—and often celebrate—conflict. But they can’t afford a radical insistence on moral purity. Driven by the imperatives of coalition building, realigners accept two principles that seem contradictory at first glance: the inevitability of disagreement and the virtues of persuasion.”

I’m often asked which politicians — in both parties — I’m watching ahead of the 2028 elections. My answer is that I’ll be looking to see if any fall under Shenk’s description of a “realigner,” showing interest in reaching out beyond their tent and creating the sort of coalition that has eluded Trump and Biden.

These politicians usually don’t fit on a simple left-right axis (although many have sought to claim the label “populist”). At points in his career — as recently as last year’s VP debate — JD Vance, with his attempts to sand the harsher edges off of Trumpism and present it as a “common sense” agenda for working families, has seemed to be trying to fit this bill, although more recently he has seemed to embrace a “radical insistence on moral purity.” Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s attempts to engage with “AOC-Trump” voters could also qualify. John Fetterman and Josh Hawley are two others who hop around the political spectrum in interesting ways.

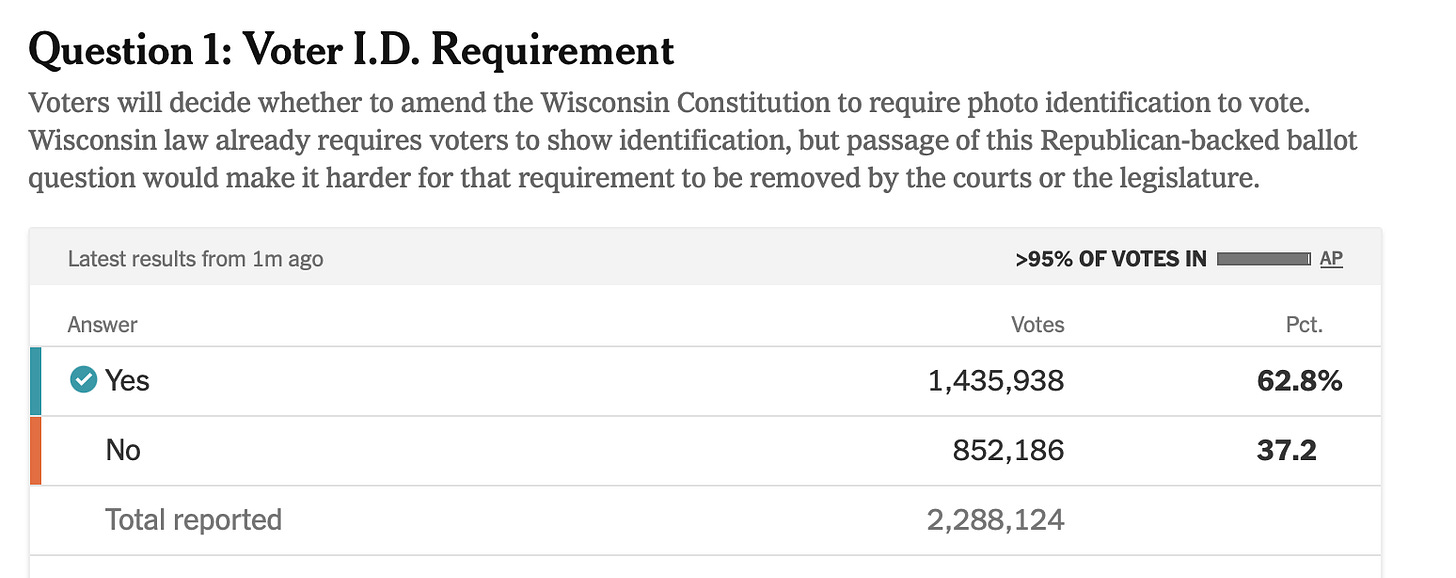

Voters largely detest both party brands, which is why it behooves a realigner to take calculated shots at their own party, picking carefully when to persuade — and when to surgically remove an unpopular position from their platform. For Republicans, one such issue will present itself in a Rose Garden ceremony later today. For the Democrats, one such issue presented itself last night: 63% of Wisconsin voters backed a ballot initiative to add a voter ID requirement, even as 55% elected a liberal Supreme Court justice. 84% of Americans back voter ID; we saw last night that this holds true even in left-leaning electorates.

Will any 2028 Democratic presidential candidates run on election security? Conversely, will any 2028 Republicans run against the tariffs? Voters like to be surprised. Predictable, packaged politicians, towing to the party line, do occasionally win national elections — but rarely do they attract long-lasting coalitions.

In the next few months and years, I’ll be looking for politicians who zig when we thought that they would zag. The last 24 hours suggests they are still in short supply.

One example of this is that the House GOP was forced to cancel votes for the rest of the week on Tuesday after nine Republicans voted down an effort to block a bipartisan measure to let new and expectant parents vote by proxy in the House.

Reportedly, some right-wing House Republicans say they will oppose any procedural measure that doesn’t block the proxy voting push. But other Republicans say they won’t vote for any measure that blocks proxy voting. So GOP struggles to keep two ends of a culture-war spectrum under one tent could hobble the rest of their agenda until the two sides reach a compromise.

Excellent column and I hope you'll continue to dig deeply into Democratic regrouping that goes beyond Booker's marathon.I happen to think it was an inspiration for us all, but also a place marker while the deep thinkers develop a real platform that will (horrors) include some elements that are currently unthinkable. Ex. If voter ID is important on both sides of the aisle, why not work at making voter IDs easily available. Continue to let us know about politicians who are willing to think outside the box.

Your insights and analysis are always treasured…especially this one. Thank you for such outstanding work!