A quick guide to Trump’s new tariffs

What you should know about U.S. trade policy, from Washington to McKinley to Trump.

Donald Trump is best understood as a man with few genuine ideological attachments. Over his decades in public life, he has flip-flopped on abortion, gun control, universal health care, transgender rights, the Iraq War, and many other issues.

But on the two issues that form the core of his political philosophy — support for immigration restrictions and opposition to free trade — he has been remarkably consistent. “America is experiencing serious social and economic difficulty with illegal immigrants who are flooding across our borders,” Trump wrote in a 2000 book. “We simply can’t absorb them. It is a scandal when America cannot control its own borders.”

His focus on trade goes back even further: “I believe very strongly in tariffs,” Trump told Diane Sawyer in an interview in 1989.

Flash forward to the 2024 campaign, and he doesn’t sound that different: “To me, the most beautiful word in the dictionary is ‘tariff,’ and it’s my favorite word,” Trump said last month.

Which brings us to Trump’s Truth Social post yesterday evening, pledging to impose a 25% tariff on imports from Mexico and Canada on his first day in office, to remain in effect “until such time as Drugs, in particular Fentanyl, and all Illegal Aliens stop this Invasion of our Country!”

Trump followed that by announcing plans to impose a 10% tariff on imports from China — on top of all existing tariffs on the country — until the flow of fentanyl, made using Chinese chemicals, into the U.S. is stopped.

Tariffs, at their most basic level, are taxes that governments impose on products coming into their country from foreign countries. The economist Douglas Irwin has written about the “three Rs” of trade policy — the three reasons governments opt to impose tariffs: revenue (the money they receive by taxing imports), restriction (imports generally drop when tariffs are imposed, giving a boost to domestic manufacturing companies), and reciprocity (a country imposing tariffs on another country in retaliation for that country imposing tariffs on them).

It was for these exact reasons that, when the first Congress met in New York City shortly after the Constitution was ratified, the first major piece of legislation they passed was the Tariff Act of 1789, which imposed a 5% tariff on nearly all imports. In a patriotic flourish, President George Washington symbolically signed it into law on July 4th.

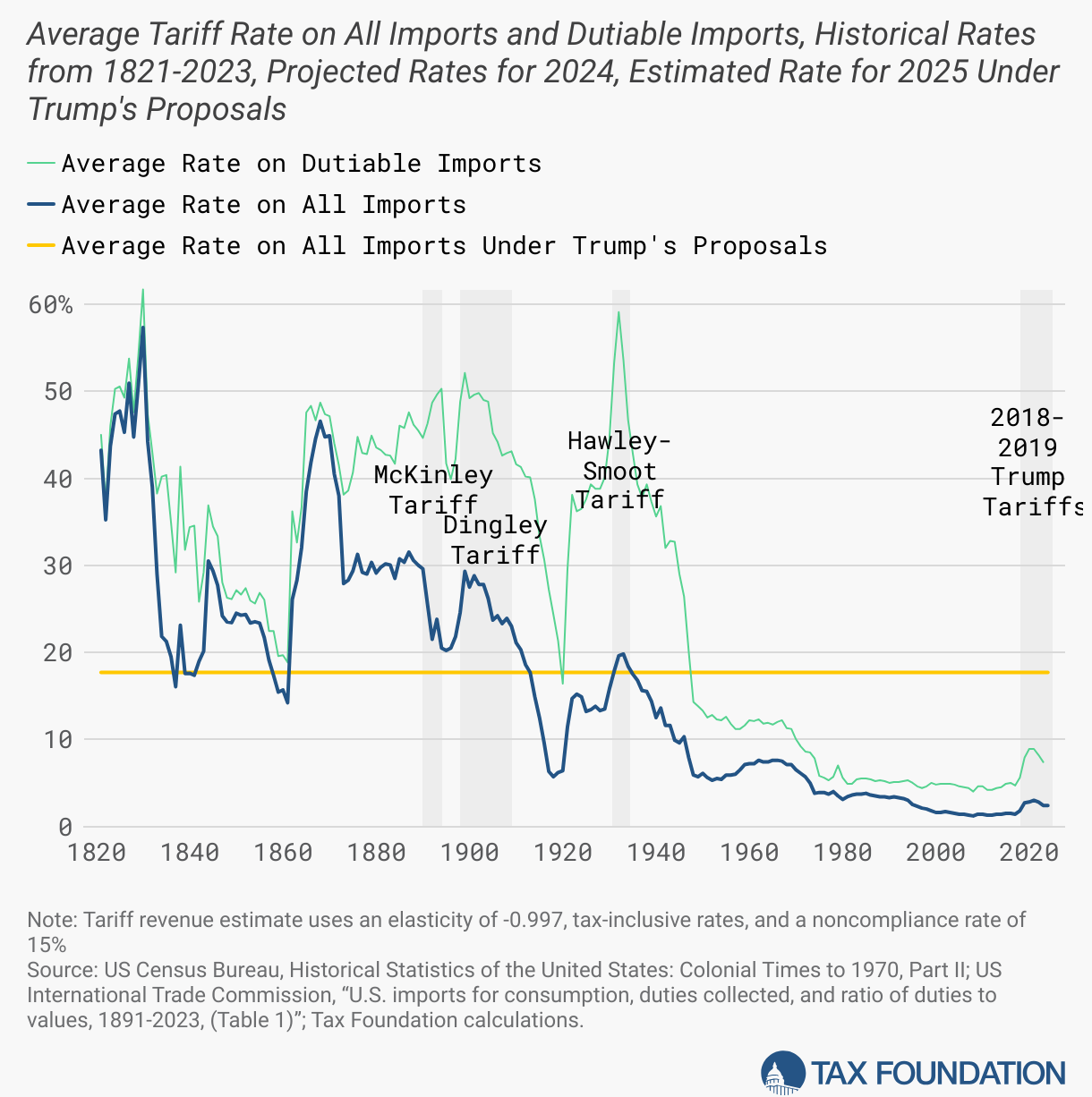

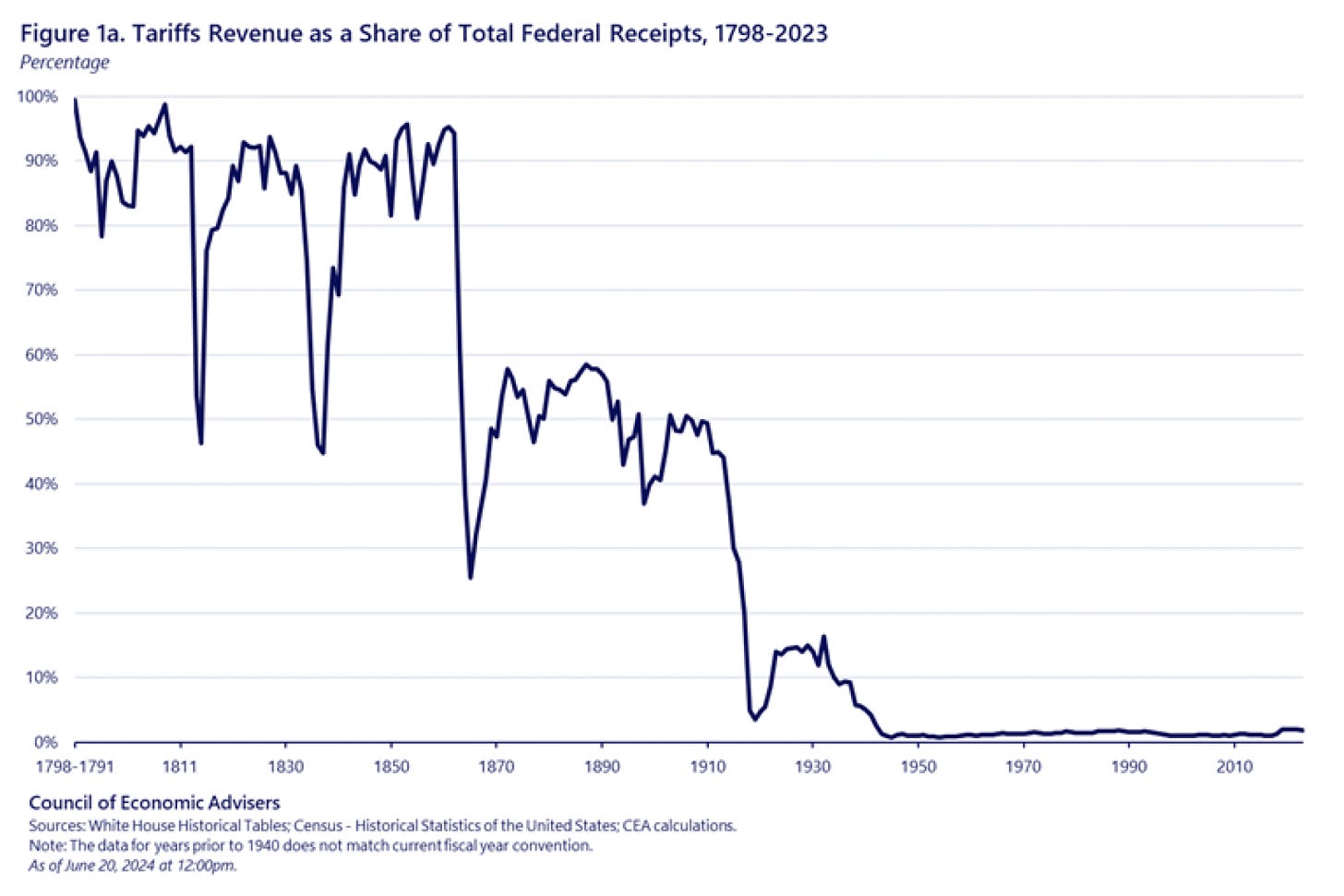

For the first half of American history, the U.S. generally kept tariffs quite high (see the first chart below); until the income tax emerged in the 1860s, and then was formalized with the 16th Amendment in 1913, they were the primary source of the U.S. government’s revenue (see the second chart).

Trump often speaks fondly of this period, specifically singling out President William McKinley, who (as a member of Congress) crafted the “McKinley Tariff” of 1890, which raised the average U.S. tariffs to nearly 50%. “He was the most underrated president,” Trump told Bloomberg this year, adding: “He made this country so rich. All he did was tariffs, we didn’t have an income tax.” (At times, Trump has suggested we should return to that policy.) In addition to referring to the first R (revenue), Trump also frequently uses the language of restriction (he has called for the U.S. to have a “ring around the country”) and reciprocity (another word Trump has called his favorite, saying that other countries are treating the U.S. unfairly and that the U.S. must respond in kind).

Trump doesn’t always mention, though, that McKinley’s tariffs weren’t all that popular. Most directly, tariffs are paid by the domestic companies that import foreign products (in our case, American companies sourcing goods from abroad) — but companies often pass the cost onto consumers, by raising their prices in response.

Tariffs can also launch countries into nasty trade wars, since one country slapping tariffs on another country usually leads to the second country slapping tariffs on the first one. That can hurt domestic industries that rely on exporting their goods abroad, since — just as U.S. companies might be less likely to import foreign goods once U.S. tariffs make it more expensive — foreign companies similarly become less likely to import U.S. goods once retaliatory tariffs from their own country makes it more expensive.

Americans did not take any of that well in 1890, and in the next midterm election, McKinley’s Republican Party suffered huge losses; in 1892, President Benjamin Harrison (a Republican campaigning on the McKinley tariff) lost to Democratic former president Grover Cleveland.

The U.S. flirtation with tariffs didn’t end there: McKinley himself would be elected president after Cleveland, and he imposed even higher tariffs than the ones he sponsored as a House member in 1890. Later, President Herbert Hoover would sign into law the Smoot–Hawley Act of 1930, which raised tariffs yet again. But the law is often blamed for worsening the Great Depression, and Franklin Roosevelt campaigned in 1932 on lowering tariffs, which he did once elected.

Note the steep drop in both above charts after the 1930s. Starting with Roosevelt, American trade policy was largely liberalized; the U.S. eventually entered into free trade agreements with many of its allies, and tariffs have remained low ever since.

Until, that is, Trump took office in 2017, and — in keeping with his long history of protectionist rhetoric — imposed new tariffs against China, Canada, Mexico, Japan, the European Union, and other countries. Trump himself lifted the tariffs on Canada and Mexico in 2019, after renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). President Biden lifted the tariffs on Japan and the EU, but kept the China tariffs in place, a reflection of the move away from free trade policies in both parties.

And now we have our most concrete idea of what Trump will do when he returns to office on January 20.

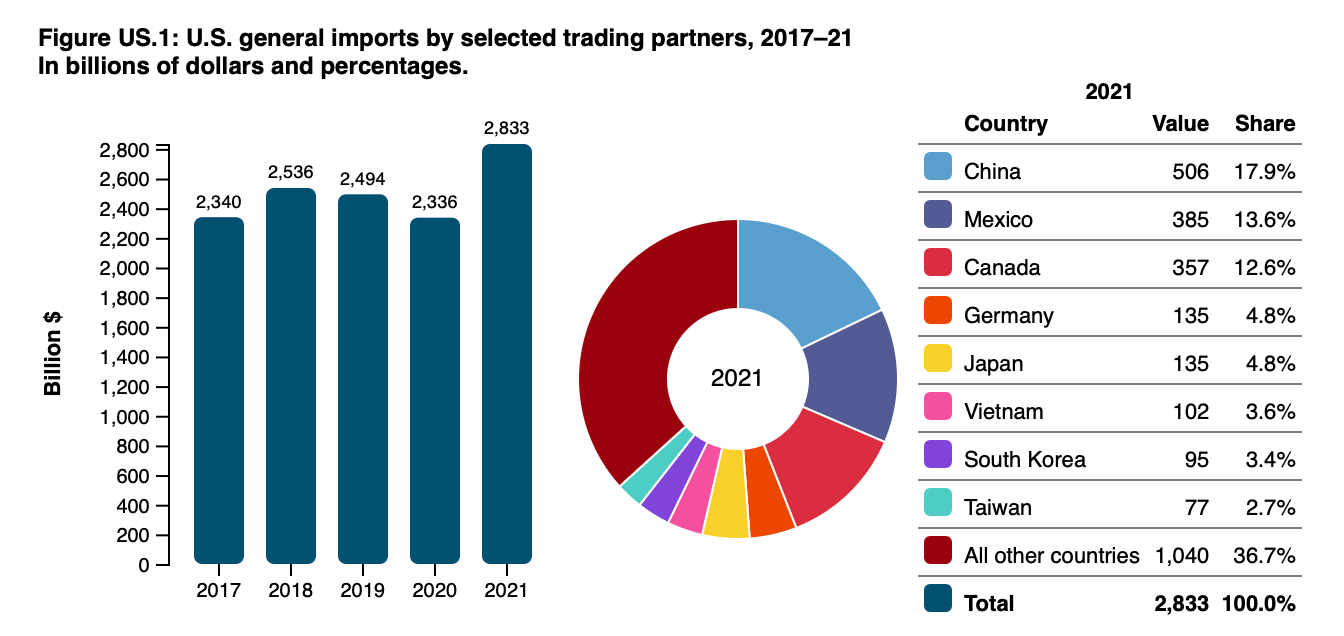

China, Mexico, and Canada — the three countries name-checked in Trump’s Truth Social posts — are the U.S.’ top trading partners. As of 2021, they accounted for a combined 44% of American imports; including both imports and exports, trade between the U.S. and those three countries totaled $2.5 trillion in 2022.

As the Washington Post writes:

U.S. imports from Mexico include cars, machinery, electrical equipment, food and beer. Canada supplies oil and gas, machinery and parts and much else. The United States relies on China for electronics, particularly phones, along with toys, furniture and plastics … Mexico supplied more than half of U.S. fresh fruit imports in 2022, according to the Agriculture Department.

If Trump’s threatened tariffs go into effect, prices for all those products in the U.S. can be expected to go up. About 80% of Canadian and Mexican exports go to the U.S., so their economies are likely to take a hit as well. The USMCA — which Trump signed himself — would be upended. Farmers and auto manufacturers are among the U.S. industries who export to these countries; they would likely suffer from retaliatory tariffs.

Trump has wide berth to enact his trade agenda without congressional approval — under the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, presidents can unilaterally impose sanctions by citing national security — but whether he will actually do so is more of an open question that you might think.

For just as long as he has preached protectionism, Trump has also repeated another lifelong mantra: “Everything is negotiable.”

In his 1987 bestseller, “Art of the Deal,” Trump advised readers to always “maximize your options,” adding: “I also protect myself by being flexible. I never get too attached to one deal or one approach.”

In that sense, the tariffs Trump threatened last night could be less of a hard-and-fast policy and more of an opening bid in negotiations, an attempt to see how far he can push China, Canada, and Mexico on fentanyl and immigration before taking office. Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau already spoke on the phone in the hours after the president-elect’s Truth post; Trudeau said this morning that they had a “good” conversation.

Here’s what hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, a billionaire Trump backer, had to say yesterday on X:

To be clear, according to Trump the 25% tariffs will not be implemented, or if implemented will be removed, once Mexico and Canada stop the flow of illegal immigrants and fentanyl into the U.S.

In other words, @realDonaldTrump is going to use tariffs as a weapon to achieve economic and political outcomes which are in the best interest of America, fulfilling his America first policy.

This is a great way for Trump to effect foreign policy changes even before he takes office.

During his first term, it was not unusual for Trump to threaten tariffs in order to extract certain concessions from other countries, and then never move forward with the threats if he was able to declare a win.

Is that what Trump is doing now? Or is he serious about slapping tariffs on America’s three biggest trading partners, throwing the economy into uncertainty? As is often the case with Trump, it’s difficult to say in advance.

More news to know

Special Counsel Jack Smith has moved to dismiss the classified documents and January 6th indictments against President-elect Trump.

Trump’s legal team found evidence that one of his closest advisers has been asking potential appointees for money in exchange for promoting them to Trump.

Biden moves to require Medicare and Medicaid to cover Ozempic.

Israel is expected to approve a U.S.-brokered ceasefire deal with Hezbollah.

The day ahead

President Biden will travel to Nantucket, Massachusetts, where he will spend Thanksgiving.

Vice President Harris will travel to Washington, D.C., from San Francisco, where she spent the weekend.

The House and Senate are on recess until next week.

“Welcome to 1933, America”

For all Trump's bluster, as H.L. Mencken said: "When all is said and done, a lot more is said than done.".