A Fitting End to the Musk Era

“Was it all bullshit?”

One of the most dramatic bureaucratic clashes of the second Trump term took place outside the headquarters of an obscure think tank called the U.S. Institute of Peace. The organization, tasked with promoting conflict resolution across the globe, was founded by law in 1984 and receives its funding from Congress, but otherwise operates mostly as an independent nonprofit.

In a February executive order, President Trump declared the institute “unnecessary” and called for it to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The next month, a team of officials from the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), reporting at the time to Elon Musk, tried to enter the institute’s headquarters in Washington; they were rebuffed and told by the nonprofit’s leaders that the government had no right to be there.

A standoff ensued; eventually, the DOGE team called in D.C. police and the FBI as backup. With law enforcement on their side, Musk’s underlings successfully marched into the building and began evicting the institute officials, making plans to shut down the think tank and sell its $500 million headquarters.

That is, until a federal judge ruled last month that DOGE could do no such thing. Accusing the Trump administration of using “brute force” to enter and then “dissemble” the institute, Judge Beryl Howell wrote in a 102-page opinion that the administration’s actions were “unlawful” for having “second-guessed the judgment of Congress,” which had decided to appropriate $55 million to the institute as recently as this fiscal year.

The U.S. Institute of Peace saga is just one example of Trump attempting to assert his executive-centric theory of government, which Musk and DOGE were most famously charged with carrying out, that suggests the president doesn’t need Congress to effect lasting policy change, and can simply carry out his wishes via executive action. I argued last week that this theory had mostly backfired, due to judicial rulings like the one from Judge Howell blocking the institute takeover.

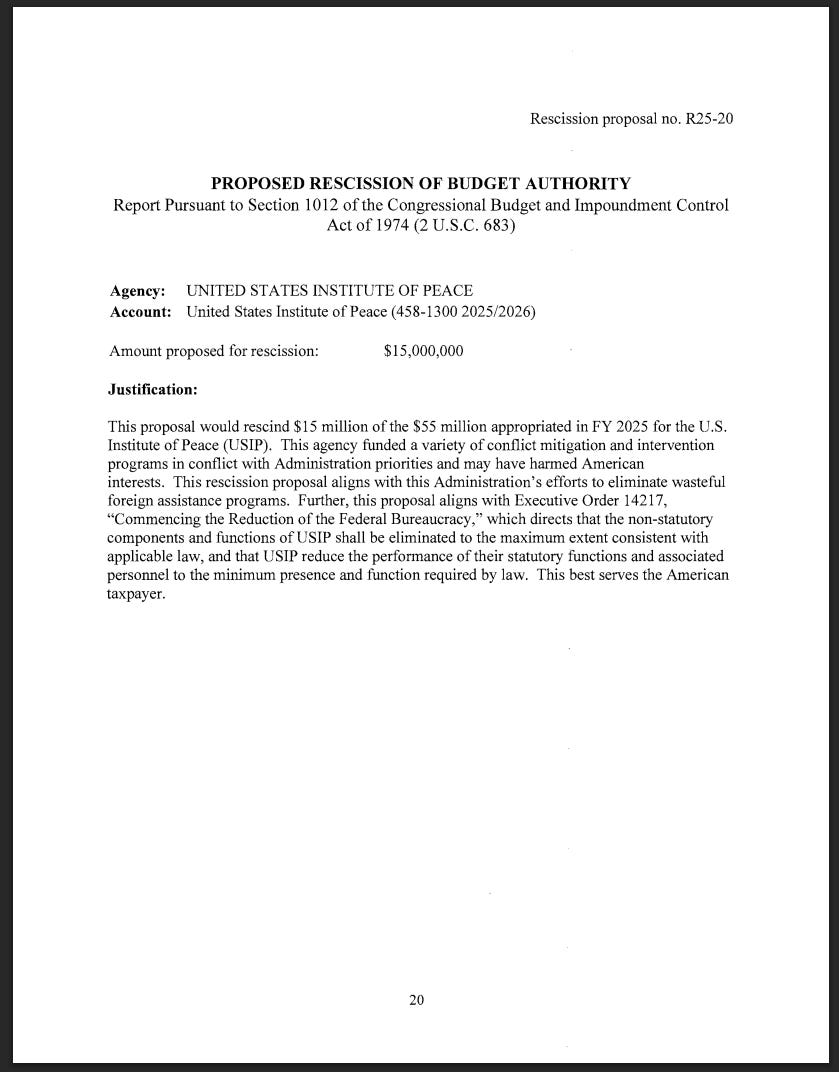

Yesterday, the Trump administration all but admitted that the theory hasn’t worked. They didn’t say that, of course, when they submitted their long-awaited rescissions package — a legal tool to codify cuts DOGE has purportedly already made — but you only have to look at Page 20 of the proposal to see that it’s the case:

The rescissions process, you see, is a legal way for the president to ask Congress to cancel funds that lawmakers have previously appropriated. It was created by the Impoundment Control Act, ironically the same Nixon-era statute that says the president can’t unilaterally refuse to spend appropriated funds, which Trump has repeatedly been accused of violating (and which his allies have argued is unconstitutional).

But the 1974 law contains a gift for Trump as well: it allows the president to submit a proposal, known as a rescissions package, laying out all the appropriated funds he doesn’t want to spend. The measure then goes to Congress; if lawmakers approve the cuts within 45 days, the president doesn’t have to spend the money. (But if the cuts aren’t approved, he does.) Notably, during the 45-day period, the president is freed from the legal obligation to spend the funds in question; also notably, a rescissions package is immune from the Senate filibuster, which means Republicans (assuming they remain united) could pass the measure without a single Democratic vote.

Why does sending a rescissions package constitute an admission of failure?

Well, take the U.S. Institute of Peace. In court filings, the Trump administration has argued that it has carte blanche over the think tank because “negotiating for peace, international engagement, and diplomacy are quintessential executive functions”; it didn’t need congressional approval to assert its will over a group that performs such duties, the White House said.

Apparently not, because the administration is now asking for congressional approval to rescind the institute’s funding. I wrote back in March that the rescissions process was an “option waiting for [Trump] if he wants to make the DOGE cuts actually stick, in a way judges can’t overturn.” Now that judges have repeatedly foiled his attempts to block spending unilaterally, the president appears to have accepted the necessity of making these cuts according to a spelled-out process.

This makes it tempting, especially now that the initiative’s chief promoter has fled Washington, to say that DOGE was “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” That’s not quite the case, of course. Numerous government employees have been laid off; foreign aid has been slashed; research grants have been canceled. (However, ongoing lawsuits could overturn even some of these “successes.”)

But the agency undeniably fell short of its promise, which was that the executive branch could cut $2 trillion from the federal budget all by itself. By its own estimation, DOGE has only cut $180 billion so far — only around $70 billion of which they’ve actually identified (and the identified cuts contain several glaring errors). Revealingly, when the administration aimed to codify DOGE’s impact with the rescissions package, only $9.4 billion in proposed cuts were put forward.

In addition to the U.S. Institute of Peace, the other targets were the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which funds NPR and PBS, all agencies that DOGE has run into legal challenges trying to dismantle unilaterally. In the end, of the U.S. Institute of Peace’s $55 million budget, the administration only asked to cut $15 million; the controversial $500 million headquarters went unmentioned. (The administration has said future rescissions packages could follow.)

Even cutting $9.4 billion — which represents approximately 0.1% of the federal budget — may be hard to get through the Republican-controlled Congress, a useful reminder that nothing gets into a spending bill accidentally. Everything has a constituency, or an interest group, or a member of Congress pushing for it. Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE) has expressed skepticism about cutting the CPB. Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) has said she will not support the proposed cuts to PEPFAR, a USAID program credited with saving 26 million lives worldwide that would have been lost to AIDS. (During Trump’s last term, he proposed the first rescissions package since the Clinton era. It was rejected by the GOP-led Senate.)

Putting aside how the rescissions package will fare in Congress, it’s worth listening to how Republicans have started talking about DOGE, now that the Trump administration is attempting to use the legislative process to cut spending.

“We thank Elon Musk and his DOGE team for identifying a wide range of wasteful, duplicative, and outdated programs,” House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) said in a statement yesterday, “and House Republicans are eager to eliminate them.” DOGE: The Great Identifier? Not quite how the supposed slash-and-burn initiative was sold to the American people back in January.

“DOGE set the table, now the Republican trifecta will deliver,” the House Rules Committee wrote on X.

Elon Musk famously held up a chainsaw at a conservative event in February. But to hear Republicans tell it, perhaps he was really only wielding a placemat this whole time.

At the same time as Johnson is moving to make his DOGE “cuts” real, Musk — who left the federal government last week — has reappeared to make the speaker’s life difficult.

The red ink of the rescissions package was still drying yesterday when the Tesla CEO took to X, which he also owns, to decry the deficit-busting Republican megabill which Congress is also currently advancing.

“I’m sorry, but I just can’t stand it anymore,” Musk wrote. “This massive, outrageous, pork-filled Congressional spending bill is a disgusting abomination. Shame on those who voted for it: you know you did wrong. You know it.”

And so we’ve arrived at the utterly predictable (and predicted) rupture in the Trump-Musk relationship, with Trump’s former “First Buddy” trashing the bill that contains most of the president’s legislative agenda, just days after the duo praised each other in the Oval Office.

Last night, Musk seemed to acknowledge the oppositional posture he was assuming, retweeting an article from the libertarian outlet Reason with a not-so-subtle headline: “It’s Rand Paul and Elon Musk vs. Donald Trump over the ‘Big Beautiful Bill.’”

The last time Musk tried to take down a major legislative package, it worked: he successfully defeated a government funding bill in December, in the weeks after his largesse helped secure Trump the White House. Then, Musk successfully rallied House Republicans against the measure, and Trump ultimately sided with Musk against Speaker Johnson.

This time, Trump is siding with Johnson against Musk. It’s an open question whether conservatives will turn against the package, which is projected to add $2.4 trillion to the deficit over the next 10 years, although many in Washington are skeptical that GOP lawmakers will turn on Trump.

Musk’s best bet at sinking the package will be members of the House Freedom Caucus, who voted for the bill last month (some grudgingly) but could turn against it depending on what changes emerge from the Senate.

Notably, the same group of Republicans have started expressing frustration in recent weeks on a separate, but related, issue: growing angry that the GOP-led Congress isn’t doing more to turn Trump’s executive orders into laws.

“Codify President Trump’s EOs now,” Rep. Andy Biggs (R-AZ) wrote on X last month. “It’s the least we could do,” Rep. Eli Crane (R-AZ) echoed. “Codify, codify, codify,” Rep. Ralph Norman (R-SC) chimed in.

This right-wing angst hasn’t gotten much attention — but, historically, when the Freedom Caucus gets frustrated, it causes problems for the rest of the party. Now, with Musk goading them on, their anger is coming to the fore at a sensitive time for Republican congressional leaders.

In a video yesterday, Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN) — who recently introduced bills to codify three of Trump’s executive orders — said that if the House doesn’t start working on rescissions or other codification efforts next week, “We’ll start stopping other legislation, because that’s all we can do.” If these lawmakers aren’t satiated, it’s not hard to imagine how rescissions could ultimately collide with reconciliation.

“If you do not put DOGE or Trump EO’s on the floor next week, I will be a NO on EVERY single rule, and I am positive I will not be alone,” Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (R-FL) similarly wrote on X.

There are practical reasons for Republicans to be hesitant about placing these bills on the floor. Several federal judges have ruled that funding held up by DOGE must be spent by September 30, the end of the fiscal year; if the rescissions package were not to pass within 45 days, it would constitute even more legal confirmation that the funds must be spent by that deadline.

One judge who ruled that DOGE’s actions at USAID were “likely unconstitutional” included in his reasoning that Congress had rejected previous attempts to defund the agency, drawing on a Supreme Court precent to say that “failure to pass legislation introduced in Congress” can be considered “indicative of congressional will.” If Congress actively fails to pass the USAID rescissions — or bills introduced codifying other Trump orders — it could make it even harder for the administration to argue in court that such orders were in accordance with congressional intent.

But there’s also a psychological element at play here. They never say it, but the demands by Burchett, Luna, and the others to codify Trump’s directives are also an acknowledgement that the executive orders are less impactful than the president says, just as the rescissions package signals that DOGE hasn’t really been cutting what it claims.

Trump, initially flanked by Musk, set out in his second term to prove the strength of the executive branch, but each time a judge stopped him in his tracks and told him he’d have go to Congress, he ended up exposing many of the presidency’s fundamental weaknesses. Amid a wider rupture between the two men, Trump now appears to be wondering about how much Musk actually accomplished — and belatedly acknowledging that his cuts will only be made real with a congressional stamp of approval.

“Was it all bullshit?” Trump reportedly asked recently of DOGE, according to the Wall Street Journal. Perhaps it was, Mr. President. Perhaps it was.

Perfectly written, Gabe. Thank you for writing this

I would like to see information on the fraud found in USAID. If it really was so corrupt we should see the evidence. Thanks