How to get Congress moving again

Good morning! It’s Thursday, April 11, 2024. Election Day is 208 days away. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

Earlier this week, I argued that the best path to a more functional U.S. government lies not in the formal creation of new political parties but in “changing the rules and norms in Congress” to allow various factions of the existing parties to work together on pieces of legislation that have broad public support.

This, I said, would address the main issue many Americans have with our political system — that it fails to get much done — without having to go through the arduous process of creating new parties (which would likely require the adoption of an entirely new election system, due to Duverger’s Law).

It took less than than 48 hours for a perfect example to arrive to illustrate this point. Last night, in an embarrassing setback for Speaker Mike Johnson, the House defeated a rule resolution that would have set up a vote on a bipartisan bill to reauthorize Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), a key government surveillance authority set to expire in eight days.

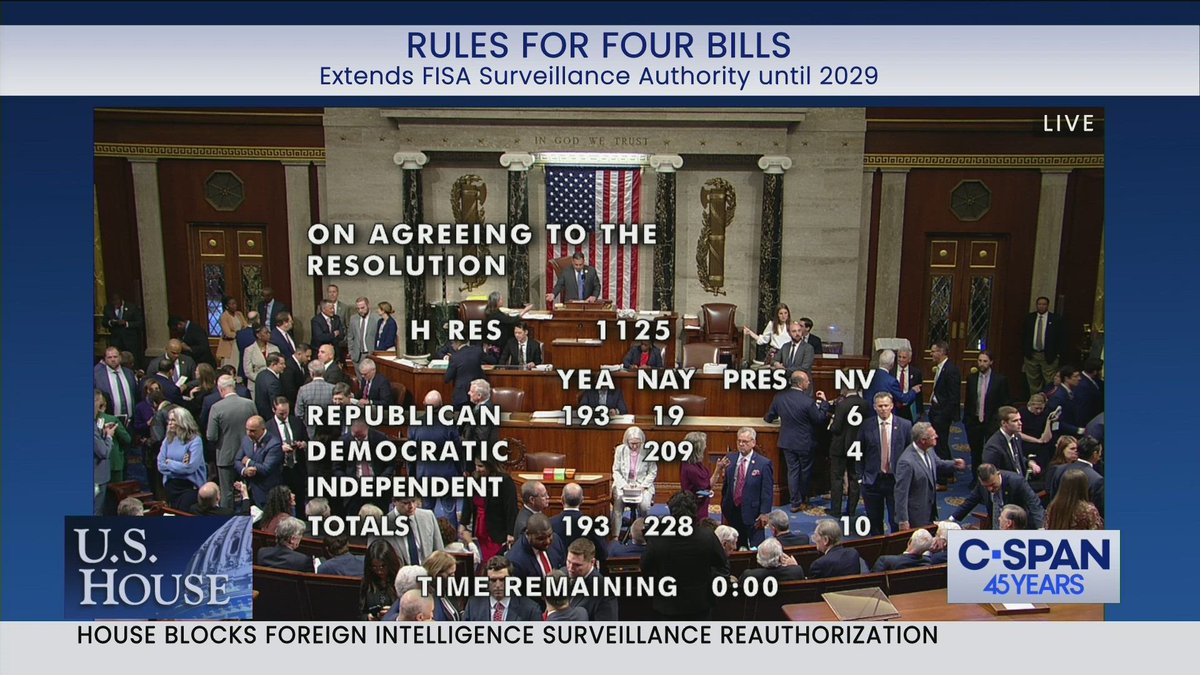

Here, courtesy of C-SPAN, was the breakdown of the vote:

For the most part, media attention has been focused on the 19 Republicans who voted against the rule — and with good reason. Normally, the majority party unanimously supports rules backed by their leadership. At a time when Johnson’s job is already on the line, it’s a big deal that so many of his own members voted against him. (For those keeping track, this is the seventh House rule vote that has failed this Congress, a modern record.)

But I also think it’s worth dwelling, for a moment, on the 209 Democrats who unanimously voted “nay” as well. After all, the main underlying bill in the rule resolution — the FISA measure — is supported by many Democrats. The White House has endorsed the package, saying that its defeat would cause the intelligence community to “lose vital insight into precisely the threats Americans expect us in government to identify and counter.” The top Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, Rep. Jim Himes (D-CT), is on record in support of the bill as well.

Of course, not every Democrat supports the measure: it includes several major reforms to Section 702, but not enough for many civil liberties advocates. But enough back it that, if they wanted to, supportive Democrats could have joined with the 193 supportive Republicans to push the rule across the finish line. (The rule also would have set up six amendment votes, four of which were bipartisan measures further reforming FISA.)

However, the norm in the House is that the minority party always votes against rule resolutions, even to advance bills they agree with, and thus, Democrats opposed the rule for this bill that a Democratic White House has called “vital.” In this case, Democrats note that the rule resolution also would have advanced three other, more partisan pieces of legislation — but there’s no reason that has to change much. Democrats could simply support the rule, and then oppose those pieces of legislation when they come up for votes.

In essence, a bipartisan piece of legislation — supported by a majority of Americans — has been blocked because of a congressional norm that prioritizes partisan divides over cooperative governance. That’s the exact type of thing I was talking about on Tuesday.

Over on Twitter, when I posted Tuesday’s newsletter, here’s one response that I received:

“This DC media fantasy about working across party lines is not in fact what happens in Europe. When a party wins a majority, as the three progressive parties you describe would win in any near term election, that party rules without having to ‘compromise’ with the minority parties.”

But I want to be very clear: I was not proposing that the U.S. adopt a multi-party, parliamentary system. As this commentator notes, parliamentary systems can be even more ruthlessly partisan than our own: in some countries, a lawmaker voting against their party on a piece of legislation (sometimes known as “crossing the floor”) can lead to the lawmaker being ejected from the party caucus altogether.

Instead, I was suggesting a small-scale reform agenda that would push the U.S. towards more effective governance while still remaining squarely within the confines of our current system, leaning into the informal “mini-parties” that already exist under the major party umbrellas. That’s the core of the “keep calm and (two) party on” philosophy.

Some of these reforms could be changes to existing norms, such as the idea that the minority party in the House has to uniformly vote against allowing consideration of bills they plan to vote for.

Other reforms could be borrowed from parliamentary governments, borrowing from the best of their structures without adopting their systems wholesale. One example is “Opposition Days,” days set aside in some parliaments for the minority party to set the floor agenda (although votes on these days are often considered non-binding). This practice could be adapted to hold a certain number of binding votes on minority-backed legislation each session. Better yet, you could have Bipartisan Days, where bills with a certain number of cosponsors from both parties are guaranteed a vote.

Still more changes could be simply be tweaks to current congressional practices. Discharge petitions, which allow for House consideration of bills with majority support, could be made simpler, rather than the extended, multi-step process they currently must go through. The Consensus Calendar, which allows for bills with at least 290 co-sponsors to be brought to the House floor, could also be improved; currently, there is a loophole that allows leadership to remove bills from the calendar by referring them to a committee.

From the left, Slow Boring’s Ben Krauss has called for week-long sessions of an “Anonymous Congress,” which would allow lawmakers to pass bills anonymously — as long as the bills receive support from 20% of the minority party, therefore alleviating public pressures that disincentivize bipartisan legislating.

From the right, Harvard Law students Thomas Harvey and Thomas Koenig have mounted a conservative case for filibuster reform, in which bills could circumvent the Senate filibuster, but only if they receive majority support in two successive Congresses — lowering the bar for legislation to get through, but only after American voters have been able to speak their will in the election cycle in between.

All sorts of congressional features currently set in stone could be similarly reformed with the idea of legislative productivity in mind. A pair of former aides to Kevin McCarthy recently proposed in the Wall Street Journal that Congress modernize its traditional committee system, in order to set up “more bipartisan select committees to serve as a catalyst for legislative action on other urgent matters” on an ad hoc basis. The model here would be the House select committee on China, which has been an “oasis of bipartisanship” and produced last month’s TikTok bill, a notable example of members crossing party lines on a major issue.

Perhaps some of these ideas would work. Perhaps some wouldn’t. (And perhaps there are others: send me yours!) But, with record numbers of Americans frustrated with congressional gridlock, isn’t it worth trying some of them? A more functional government wouldn’t require major upheaval; it’s possible that a few tweaks here and there would start to open the floodgates.

Of course, personnel is important too — and some of you may be skeptical that our current set of lawmakers are capable of working together on major legislation, even if rules were modified to allow such bipartisan bills to advance.

That’s a skepticism I hope I’ve partially disproven by my weekly Friday newsletters, which chronicle under-the-radar bipartisanship in Washington. Tomorrow, for example, I’ll be writing about a comprehensive data privacy bill — which would be our nation’s first — that was introduced this week across party lines. Similarly important measures are frequently introduced with bipartisan buy-in; often, the real challenge is getting these bills to the floor, which changes like the ones I’ve outlined would alleviate. Many of these bills would easily receive majority (or even supermajority) support in the House or Senate, if only they were allowed to receive a vote.

With these changes, rather than tolerating a permanent divide between the two big parties, the informal mini-parties I described on Tuesday could be empowered to work together where they agree, while still opposing each other when they don’t. To again use the Echelon Insights labels, “Labor” and “Conservative” members could work together on family policy. “Green” and “Nationalist” members could try to form a majority behind a tech antitrust bill, or on measures limiting foreign interventions. And so on.

Parties can be a helpful sorting mechanism in a democracy, but when they are expected to vote together as a bloc on every issue, they serve to stifle government productivity rather than encourage it.

Obviously, these changes would require congressional leaders to give up some amount of power, both over what lands on the floor and over their members, unloosening the shackles that currently emphasize rigidity (predictable party-line votes) over fluidity (ad hoc, bipartisan coalitions of members forming to support or oppose pieces of legislation on the merits).

But, in the interest of their institution — with its 15% approval rating — and even their own parties, which would be able to show voters that they have implemented more of their priorities, some of these reforms should be considered, allowing for a slight shift in the fluidity direction. Not every day, not on every vote — but sometimes.

This would be best understood not as a movement towards a parliamentary system, in which party leaders exert even more control over their members, but towards the party system of earlier American history, which was much looser and allowed for more frequent aisle-crossing on big issues. For a more functional government, we don’t need to re-invent the wheel; we could simply set back the clock.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

- Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

- Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

- Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe