Keep calm and (two) party on

Why No Labels didn’t work — and the next group trying the same thing won’t either.

Good morning! It’s Tuesday, April 9, 2024. Election Day is 210 days away. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe here. If you want to contribute to support my work, donate here.

Let’s kick off this morning with a reader question.

Rob R. asks: “I’m curious what you and others ‘in the know’ think about No Labels not being able to put out a candidate? What does it say about American politics and American society?”

I don’t think it tells us much about American politics that we didn’t already know. In fact, I don’t think it tells us much about American politics that Maurice Duverger wouldn’t have been able to tell you 70 years ago. For those unfamiliar, Duverger is the French political scientist who wrote the following in 1954:

“The general influence of the system of balloting may be set down in the following three formulae: (1) proportional representation encourages a system of parties that are multiple, rigid, independent, and stable (except in the case of waves of popular emotion); (2) the majority system with two ballots encourages a system of parties that are multiple, flexible, dependent, and relatively stable (in all cases); (3) the simple-majority single-ballot system encourages a two-party system with alternation of power between major independent parties.”

Of his three hypotheses, Duverger wrote that #3 was the closest to a “true sociological law”; indeed, it is known as “Duverger’s Law” today. The United States of course, uses “simple-majority single-ballot” voting — also known as a “first-past-the-post” system — which means, according to Duverger, it is akin to fact that the country can have only two viable political parties.

No Labels’ failure only proves that.

In my time covering politics, No Labels is only the latest group to try to buck Duverger’s Law — and promptly discover what happens when you run afoul of it. In 2012, an organization called Americans Elect tried to stage a very similar third-party effort. Just like No Labels, they planned to run a presidential ticket with both a Democrat and a Republican on it; they floated big names who could carry their banner (Hillary Clinton! Jon Huntsman!); poured a lot of money into the operation ($35 million); and then found almost no interest from any of their potential candidates.

Americans Elect was, at least, set up to be more democratic than No Labels: their candidate was supposed to be selected on the Internet in the first-ever “national online primary,” unlike No Labels’ more shadowy process. (Thomas Friedman rhapsodically wrote at the time that “what Amazon.com did to books, what the blogosphere did to newspapers, what the iPod did to music, what drugstore.com did to pharmacies, Americans Elect plans to do to the two-party duopoly that has dominated American political life.” Um, not so much.) But, still, gimmicks aside, it was the same basic idea. (It should also be noted that the electorate showed almost as little interest as their courted candidates. Very few voters participated in the online primary.)

Four years before Americans Elect, a group called Unity08 similarly tried to run a bipartisan fusion ticket, this time with actor Sam Waterston as its spokesman. Four years after it, a number of different groups launched furious efforts to find a centrist unity candidate for 2016, from low-profile contenders like David French to perennial-potential-unity-candidates Michael Bloomberg and William McRaven, plus David French. None worked. (Former CIA operative Evan McMullin ended up running, drawing 0.5% of the popular vote.) In 2020, Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz’s third-party trial balloon ended before it began.

Now, maybe all these potential candidates were scared away by the vaunted Uniparty, after the establishment poobahs put the Fear of Pelosi in them and told them to drop out or else. Or, more likely, as happened this year, these very smart former mayors, governors, senators, admirals, and CEOs ran the numbers and realized a third-party effort has no shot.

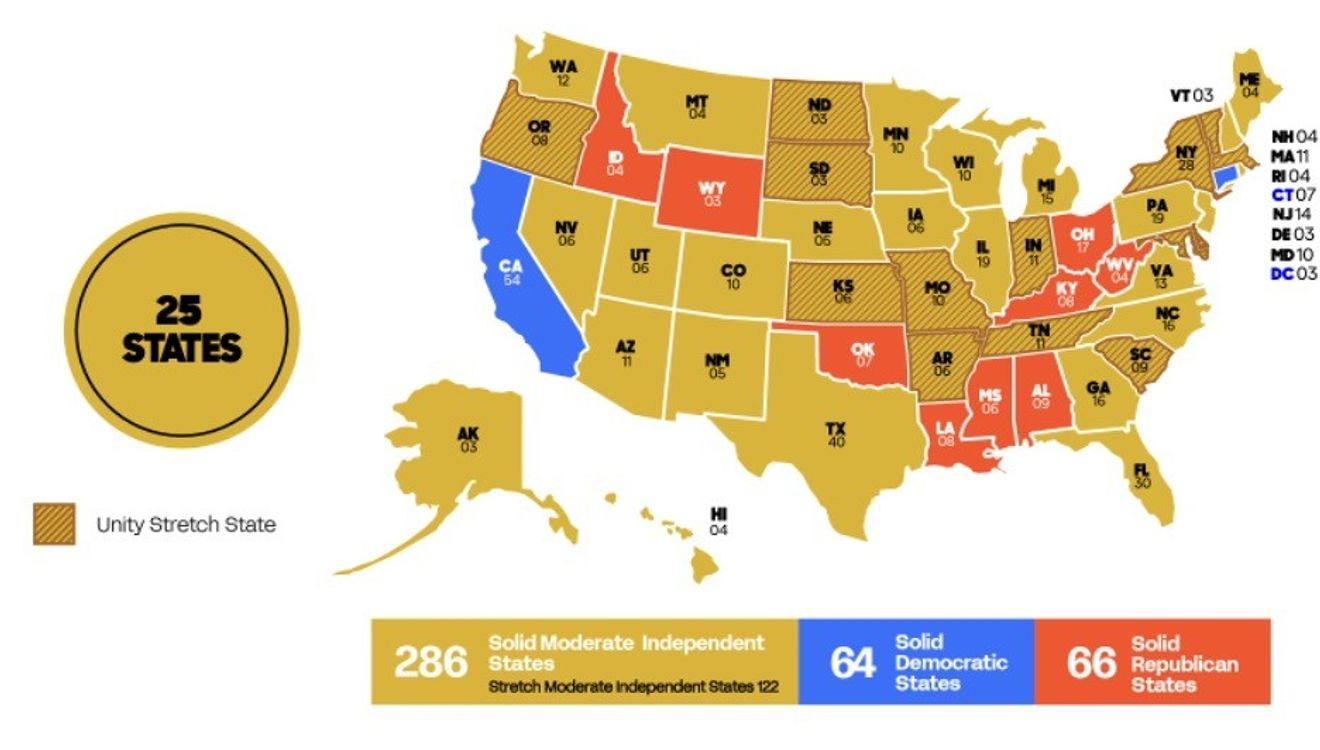

Until the very end, when they finally bowed to reality and pulled the plug, No Labels tried to argue the opposite, even at one point producing this fantastical map purporting to show they could win 286 electoral votes:

The organization said their source for this map was polling data which showed a “whopping 59% of voters say they would consider a moderate independent ticket in the 2024 race.”

For the record, I absolutely believe that that’s what their polls were telling them. A public poll, conducted by Gallup, showed U.S. support for a potential third party as high as 63% last year. The issue is, data about American voters and political parties can often be very deceiving, as No Labels (and Americans Elect and Unity08 before them) has now learned. That’s the first big takeaway to understand here.

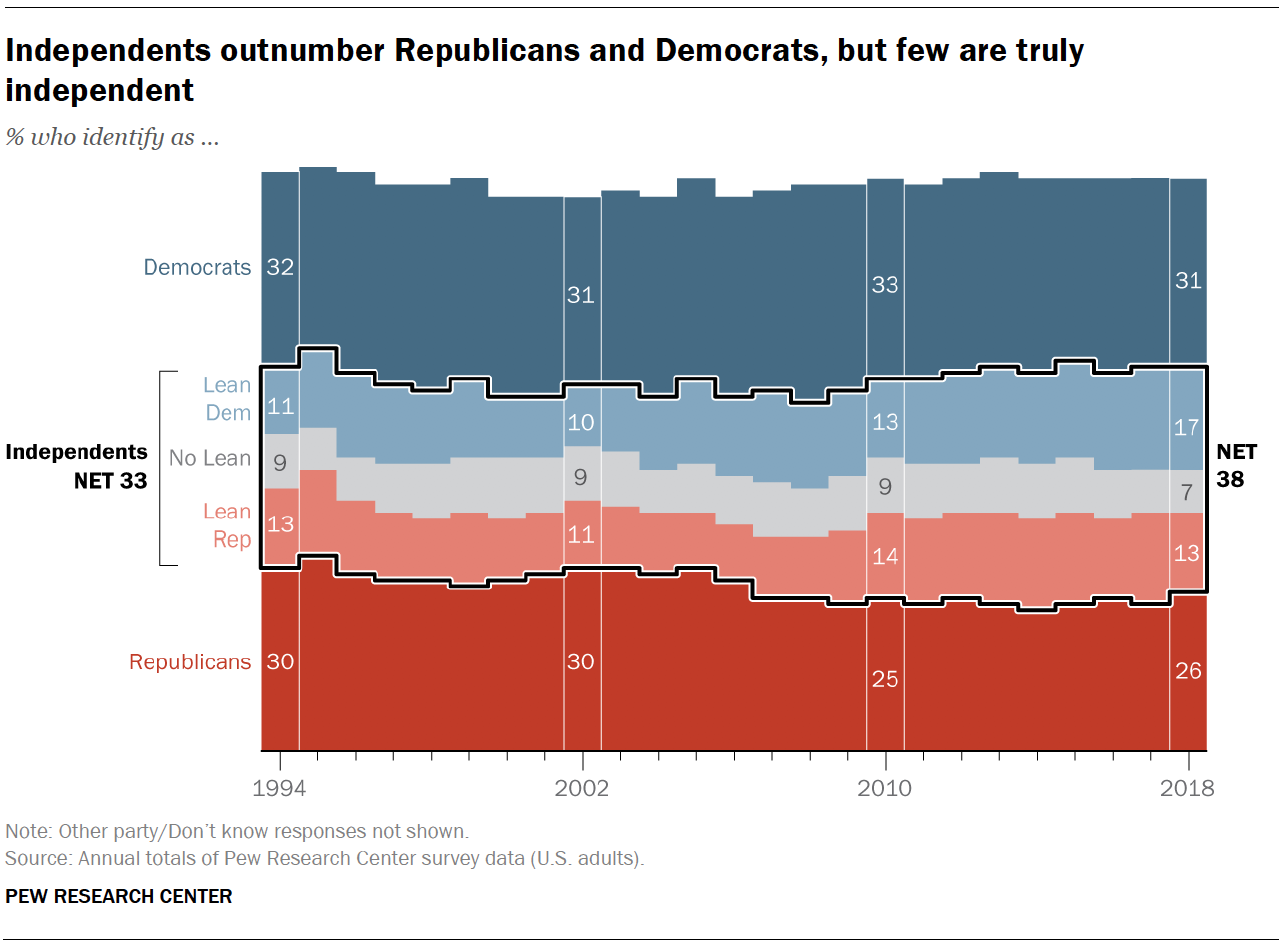

It’s often cited, by groups promoting third parties and by others, that somewhere around 40% of Americans consider themselves political independents. But you have to look at the finer details, like this 2019 Pew poll does. In the poll, if you take away Independents who say they “lean” towards one party or the other, its original number of 38% Independents — more than either party! — drops down to a mere 7% (and even that might be overstating the number of “true” Independents, since even more people likely lean one way or the other and tell themselves they don’t).

If you’re wondering how predictably partisan these “lean” Independents are, the answer is “very.” In 2012, for instance, political scientist Alan Abramowitz calculated that 87% of Democratic-leaning Independents voted for Barack Obama, while 86% of Republican-leaning Independents voted for Mitt Romney, using data from the well-respected American National Election Study. 78% of the Democratic-Independents voted a straight Democratic ticket that year; 72% of the Republican-Independents voted a straight Republican ticket.

The same effect shows up year after year. In fact, one of my favorite political statistics comes from the excellent book “Why We’re Polarized” by Ezra Klein, who notes:

In his important paper “Polarization and the Decline of the American Floating Voter,” Michigan State University political scientist Corwin Smidt found that between 2000 and 2004, self-proclaimed independents were more stable in which party they supported than self-proclaimed strong partisans were from 1972 to 1976.

Think about that: “Today’s independents vote more predictably for one party over the other than yesteryear’s partisans,” as Klein summarizes. “That’s remarkable.”

So all those people who say they might vote for third party? They almost certainly won’t. In 2020, according to CNN’s exit polling, 5% of Independents — who are presumably the target audience for third party candidates — voted for candidates not named Trump or Biden. In 2016, 12% of Independent voters cast ballots for third party candidates.

In cycle after cycle, we see third-party candidates perform a lot better in polls than at the ballot box. At one point in 2016, a CNN poll showed Jill Stein and Gary Johnson combining to capture 18% of the presidential vote; in reality, they received a combined share under 5%. And that was a year that was a high watermark for modern third parties. Similar dynamics have played out in other election years, and likely will again this year: history shows that Stein, Cornel West, and Robert Kennedy, Jr. will all underperform their polling.

And that puts aside the quirks that separate the U.S. from even a normal first-past-the-post system, which (as Durverger tells us) already makes third-party bids challenging. Third party candidates often struggle to navigate our patchwork ballot access process. Then, even candidates who get on all 50 state ballots and perform well nationally — like Ross Perot, who took 18% of the vote in 1992 (still less than polls often showed him) — routinely fail to make a dent in the Electoral College. No third-party candidate, even prominent ones like Perot in 1992 or John Anderson in 1980, has received a single electoral votes since 1968. There was simply no way No Labels was going to get 268 electoral votes. In all likelihood, it was poised to receive zero, and their withdrawal is simply an acceptance of that reality. When it comes to third-party candidacies, American voters are a tease.

Where does that leave us? Absent major reforms to our electoral system, the kind that would allow us to break out of the confines of Duverger’s Law, a viable third party is simply not possible in the U.S. The reform must precede the candidacy, not vice versa, as No Labels has now learned.

But let’s take this a step further. Personally, I think moving to a voting system — such as proportional representation — that lends itself to multi-party democracy could be an interesting experiment. But I’m also not sure it’s necessary, or the best use of reformers’ time. The data on Independent voters — who largely always vote straight tickets and balk at third-party options when they’re presented with them — leads me to believe that our current system might actually be aligning with the electorate’s true preferences more often than we think (or are willing to admit in an era when its fashionable to declare independence and dismiss the two parties).

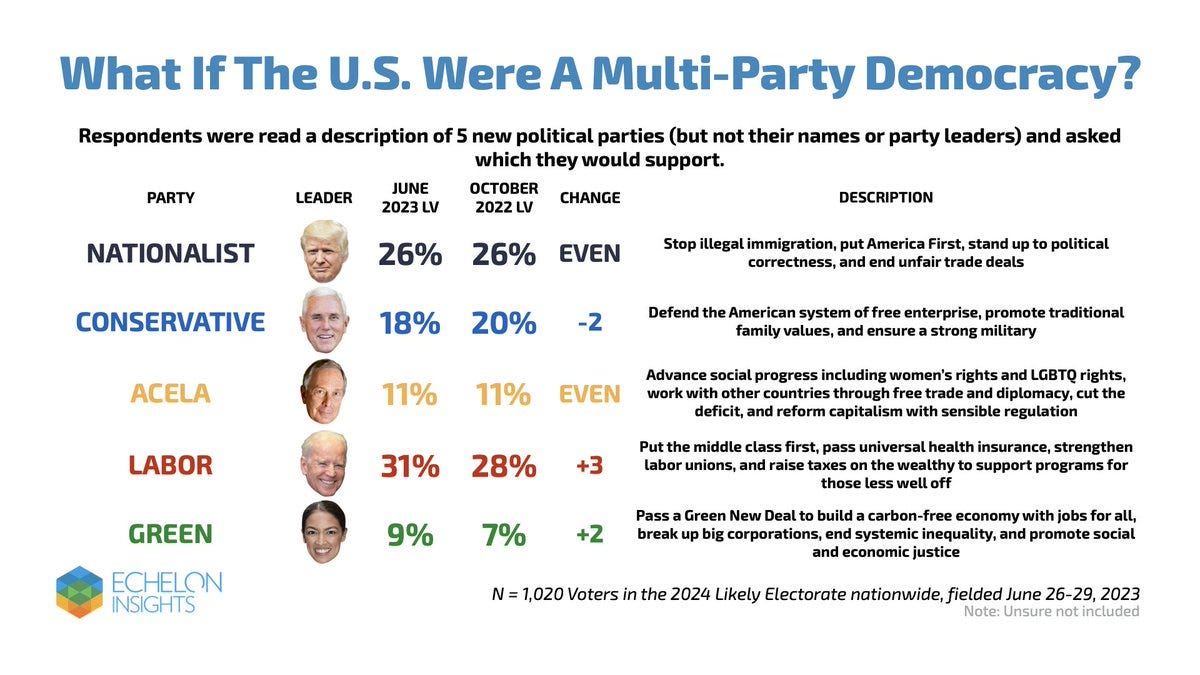

The polling firm Echelon Insights regularly conducts great surveys where they ask how American voters would fall into in an imagined five-party system. Below are their most recent (July 2023) results:

When I look at this breakdown, it seems to me that our government has already naturally achieved a similar outcome as it would under explicit multi-party rule. If this polling is correct, in a parliamentary-style U.S., you would expect Joe Biden (or, more realistically, a younger, Biden-like figure) to be prime minister. “The Squad” would be a sizable-but-far-from-dominant faction of his coalition. You would expect the largest faction of the minority coalition to be Trump-style Republicans, with more traditional conservatives as the second-largest segment. And then you’d have centrist Joe Manchin types sprinkled into both coalitions, perhaps represented by the House Problem Solvers Caucus, which is evenly split between both parties. In case you haven’t noticed, I just described the current state of the U.S. Congress. (The Problem Solvers Caucus, for example, makes up precisely 11.7% of Congress, exactly matching the proportion that the “Acela” faction makes up of the electorate.)

We essentially have two large party umbrellas, with segments underneath them that almost perfectly represent the sizes of the mini-parties that a multi-party system would bring us. The makeup of these coalitions then shift over time, effectively creating new umbrella parties but keeping the same names. (The Trump-era “Republican Party” has the same name as the Bush-era “Republican Party,” but, in practice, its coalition has taken many voters from the mini-parties that made up the Bush-era “Democratic Party” and conceded many voters to the modern-day “Democratic Party” umbrella.)

Or, as Paul Ryan once put it: “We basically run a coalition government without the efficiency of a parliamentary system.”

In my opinion, then, the biggest step that needs to be taken to produce public policy that mimics U.S. public opinion is not the explicit creation of a new party, or a unity fusion ticket. It’s changing the rules and norms in Congress (the physics!) that prevent lawmakers from, say, the “Nationalist” and “Green” factions from working together to pass bills they agree on, as they might be able to in parliamentary system, because our umbrella parties are so rigid and often prevent such cooperation.

Perhaps No Labels was a Trump-funded front, as some Democrats allege. But let’s, for a moment, accept the premise that they were honestly working to give representation to political independents who feel the two-party system isn’t working for them. Or, instead, I’ll address this to the next group that will crop up promising a third party for these voters, since we know there will be a next group. Here’s my two-step diagnosis on why these movements never work:

1. They focus too much on the presidency and not enough on Congress, who are the prime movers of American public policy (certainly the policy that sticks). If you want to install government actors who agree with you, it is much easier to start with Congress (with its smaller voting divisions and lack of Electoral College) than the presidency. And, your unity ticket won’t be able to do much unless Congress is made up of legislators in a similar mold. (This, by the way, is a lesson Donald Trump has learned. To use the Echelon language, in his first term, he was elected as a “Nationalist” president with a “Conservative” Congress and failed to enact much policy as a result. That’s why he’s focused on down-ballot endorsements during his interregnum period. If he wins a second term, his party coalition will be much more dominated by “Nationalist” Republicans, allowing for more policy successes.)

2. They focus too much on building new parties and not enough on implementing smaller reforms that might grease the skids of government and allow the existing mini-parties within our larger party umbrellas to work together. As it stands right now, our government has essentially been kept open by a coalition of Labor, Acela, and Conservative legislators. Why not try to find ways to make it easier for this coalition (or others!) to pass bills that aren’t just about averting government shutdowns? It would be much easier and more effective to improve our government by putting structures in place that allow the mini-parties within the two umbrellas to work together than to go through the time-consuming process of dispensing with the umbrellas altogether and slotting in five mini-parties that essentially mimic how Congress already looks now. Let’s try to unloose the shackles of the current umbrella parties before creating new ones. Perhaps it’s possible to bestow our system with some of the efficiencies of a parliamentary system, as Ryan put it, without going full tilt.

Ironically, both of these lessons are ones that No Labels used to understand. They are the sponsors of the Problem Solvers Caucus, which — for all its problems in reality — was set up in theory to achieve these exact two goals: focus on installing like-minded centrists in Congress, and then put them to work breaking down barriers that prevent cross-partisan governance.

Maybe, then, the real thing No Labels’ journey tells us about American society is that our current media climate and economic incentives lead people to gravitate from serious, substantive missions towards shiny, unattainable goals. No Labels’ failure is a valuable reminder that projects of the latter type may grab more money and attention, but they are ultimately destined to fail every time.

So, again, nothing we didn’t know before.

Thanks for reading.

I get up each morning to write Wake Up To Politics because I’m committed to offering an independent and reliable news source that helps you navigate our political system and understand what’s going on in government.

The newsletter is completely free and ad-free — but if you appreciate the work that goes into it, here’s how you can help:

Donate to support my work or set up a recurring donation (akin to a regular subscription to another news outlet).

Buy some WUTP merchandise to show off your support (and score a cool mug or hoodie in the process!)

Tell your family, friends, and colleagues to sign up at wakeuptopolitics.com. Every forward helps!

If you have any questions or feedback, feel free to email me: my inbox is always open.

Thanks so much for waking up to politics! Have a great day.

— Gabe