Zombies Are Loose in the Government

Whether to rein them in will be one of the Supreme Court’s first tests of Trump’s power.

When you were in elementary school, you probably learned a schema of the federal government that looked something like this:

The reality is a bit more complicated. As I wrote a few weeks ago, the lines of responsibility of the three branches of government actually overlap quite a bit more than that model lets on — including in some ways that have never really been tested.

What would happen if Congress, which has the power of the purse, defunds the White House or the Supreme Court and then passes the law over a presidential veto, denying the other branches money to carry out their operations? Or if the executive branch, which is the one actually charged (through the Bureau of the Fiscal Service) with sending out the payments that the legislative branch approves, declines to spend the money Congress tells it to? Normally, you’d say the judicial branch could step in…but then you’d remember that the judiciary’s enforcement arm, the U.S. Marshals Service, is housed within the executive branch. I told you there’s a lot of overlap.

Those types of scenarios would send us into constitutional crisis territory, but there are also more normal, less acute ways that the simple legislative-executive-judicial branch model doesn’t hold up.

One of them is independent agencies. Most arms of the government operate pretty much the same: Congress funds them, and the president supervises them. That’s how, say, the State Department works, or the National Park Service. But there are other agencies where it’s more complicated. The Federal Reserve, for example, isn’t funded by Congress, and the president doesn’t get a say in its decisionmaking. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, in turn, is funded by the Fed.

The executive branch also includes officials, like immigration judges, whose functions are judicial in nature, and even one — the vice president — who presides over the Senate, the upper chamber of the legislative branch. Still more agencies, like the Federal Trade Commission, are acknowledged to be both quasi-judicial and quasi-legislative, since they have the ability to decide legal disputes and issue regulations. The interbranch lines are sometimes blurry.

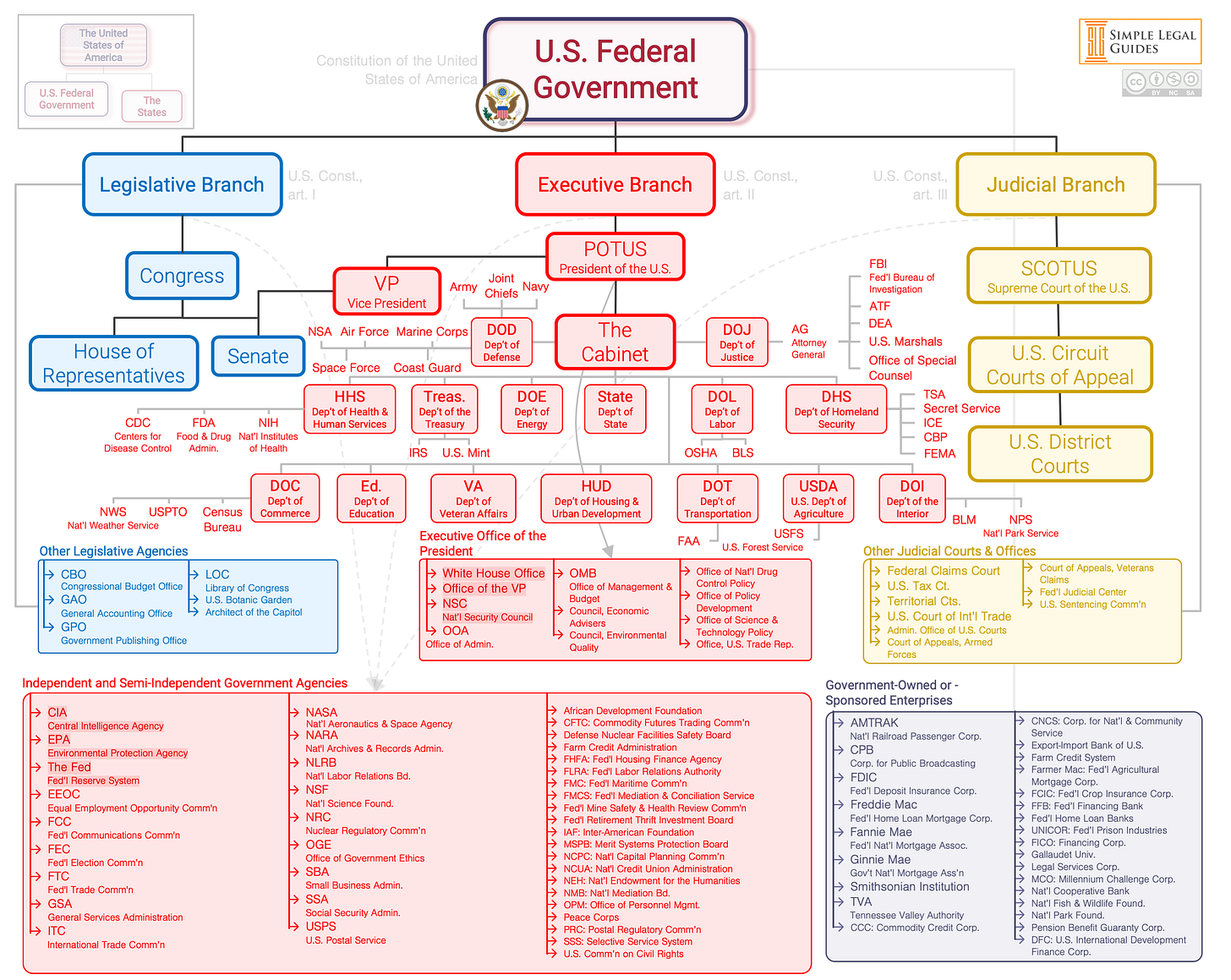

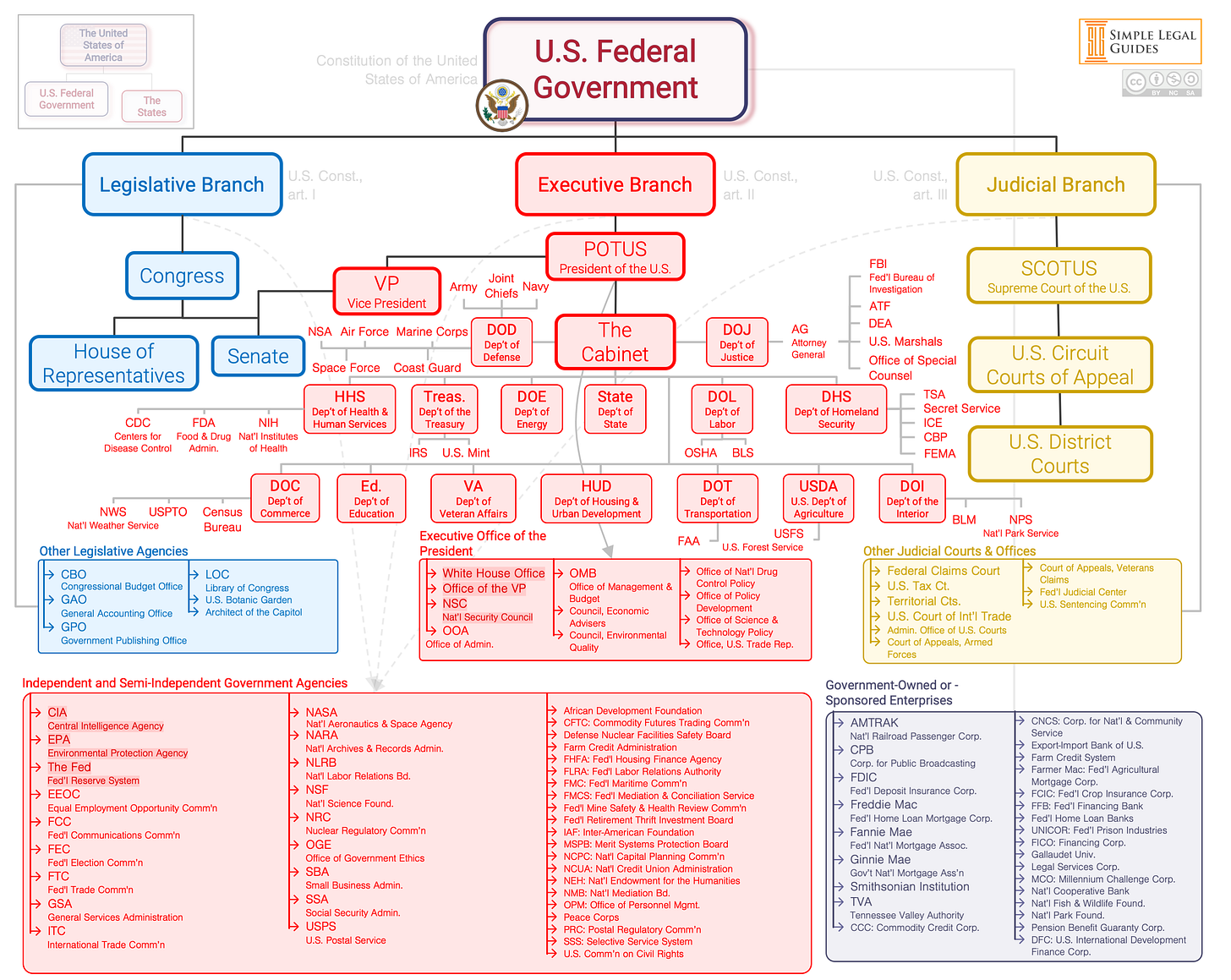

Here’s a more accurate depiction of what our government looks like, in all its confusing glory:

No matter your opinion on the legality of this system, it’s clearly something of a fragile patchwork, with agencies that technically fall under the executive branch but also aren’t fully accountable to it. People have been warning about this almost since the advent of independent agencies. Before there was Elon Musk, there was Louis Brownlow, a political scientist who chaired the “President’s Committee on Administrative Management” under Franklin Roosevelt — sort of the original DOGE, an effort to reorganize government right at the beginning of the modern administrative state.

In its final report, the Brownlow Committee referred to independent agencies — many of which had emerged as part of FDR’s New Deal — as making up “a headless ‘fourth branch’ of the Government, a haphazard deposit of irresponsible agencies and uncoordinated powers.” The report added:

The independent commissions present a serious immediate problem. No administrative reorganization worthy of the name can leave hanging in the air more than a dozen powerful, irresponsible agencies free to determine policy and administer law. Any program to restore our constitutional ideal of a fully coordinated Executive Branch responsible to the President must bring within the reach of that responsible control all work done by these independent commissions which is not judicial in nature. That challenge cannot be ignored.

At the same time, the commissions present a long-range problem of equal or even greater seriousness. This is because we keep on creating them. Congress is always tempted to turn each new regulatory function over to a new independent commission. This is not only following the line of least resistance; it is also following a fifty-year-old tradition.

Reader, the challenge was ignored. Independent agencies kept on being created, just as Brownlow predicted, and they kept on headlessly hanging in the air, a governmental question mark.

And here we arrive at the Trump angle. (You just knew there would be a Trump angle!) Trump is trying to finish what Brownlow started, by bringing the independent agencies — an alphabet soup that includes the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), to name a few — under presidential control once and for all.

Last week, Trump signed an executive order that declares “it shall be the policy of the executive branch to ensure Presidential supervision and control of the entire executive branch” — including the (suddenly-not-very-independent) independent agencies. These agencies, which previously operated with little presidential oversight, will now be required to submit their proposed regulations to the White House for review.

Trump has also attempted to fire several independent agency officials, including commissioners on the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the chairwoman of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

The executive order and the firings are an attempt to re-envision the independent agencies from how they were understood both by Congress at their creation and by the Supreme Court in subsequent rulings: as bodies within the executive branch, but outside the president’s purview.

In the landmark 1935 case, Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Roosevelt could only remove an FTC commissioner for the specific reasons allowed by Congress. (The commissioner in question, William Humphrey, had died by the time the case was brought, hence its initiation by the executor of his estate, whose name the court apparently never bothered to learn.)

Here’s what the court had to say then:

We think it plain under the Constitution that illimitable power of removal is not possessed by the President in respect of officers of the character of those just named. The authority of Congress, in creating quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial agencies, to require them to act in discharge of their duties independently of executive control cannot well be doubted, and that authority includes, as an appropriate incident, power to fix the period during which they shall continue in office, and to forbid their removal except for cause in the meantime. For it is quite evident that one who holds his office only during the pleasure of another cannot be depended upon to maintain an attitude of independence against the latter’s will.

The 1935 court had no problem with the whole blurry-lines conception of government. The FTC, the justices said, “was created by Congress as a means of carrying into operation legislative and judicial powers, and as an agency of the legislative and judicial departments,” not just the executive branch.

The Trump administration is not shying away from the fact that its firing of independent agency officials violates the spirit of Humphrey’s Executor. In fact, in a letter earlier this month, the Justice Department notified lawmakers that it plans to “urge the Supreme Court to overrule that decision.” The administration is actively trying to force a legal fight over the nearly century-old precedent.

So, we’re all caught up on this governmental gray area — and how it’s about to be tested in the courts. Now, get ready for things to get even grayer.

One of the independent agency chiefs who Trump has tried to fire is Hampton Dellinger, the Biden-appointed head of the U.S. Office of Special Counsel (OSC), which is charged with protecting the rights of federal employees, especially whistleblowers. (This is different than the Justice Department special counsels, like Robert Mueller or Jack Smith, although they also occupy complicated constitutional ground.)

By law, OSC heads — like other independent agency officials (including Humphrey, the late FTC commissioner) — can only be fired for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” But when Trump dismissed Dellinger with a letter on February 7, he didn’t name any of those reasons. So Dellinger sued, and an Obama-appointed district judge temporarily halted his firing, ruling on February 10 that Dellinger could remain in office while the case went through the courts. The Trump administration appealed directly to the Supreme Court, making this the first Trump-related dispute to reach the justices since the beginning of his second term.

Rebuffing Trump, the court declined to block the judge’s order, which the judge then extended yesterday, allowing Dellinger to remain in his job at least through Saturday.

Things get even stickier from here. Separately from the independent agency firings, the administration has fired thousands of probationary employees, federal workers who are relatively new to their current positions. Six of them sought relief from Dellinger, following the proper process for federal employees who believe they have been fired for reasons other than performance (which is generally the only reason Congress has said they can be fired).

Dellinger agreed with the workers, and — again, following the proper process — recommended their cases on February 21 to the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), a self-described “independent, quasi-judicial agency in the executive branch,” which has the power to pause a federal employee’s firing. The MSPB also sided with the six employees, ruling Friday that they could keep their jobs at least through mid-April as the OSC continues to investigate.

But here’s the catch: Trump also tried to fire the chair of the MSPB this month; she, too, is still in her job because a federal judge paused her dismissal.

So you have six federal employees who were fired, but still temporarily hold their jobs, because of the recommendation of a federal official who was fired, but still temporarily holds his job, which was then approved by an agency led by yet another official who was fired but still temporarily holds her job.

Now you see what I mean by zombies! The United States government is currently populated by a bunch of half-dead half-fired officials, who continue to function in their roles — and are even spawning new zombie workers by re-hiring other fired officials, despite sort of being terminated themselves. Annnnnd many of these zombie officials work in agencies that were already arguably legal gray areas to begin with.

Got all that?

This whole mess already reached the Supreme Court, which basically decided to stay out of it (over the objections of liberal Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson, who would have formally rejected Trump’s request, and conservative Justices Neil Gorsuch and Samuel Alito, who would have accepted it).

But the situation is worth watching because it will be back in front of the court before long. In fact, it seems primed to be the first major Supreme Court battle of Trump 2.0, the first opportunity for the justices to weigh in on the president’s attempts to expand executive power. Just last night, the Justice Department wrote the justices and asked them to reconsider their decision not to intervene in the Dellinger case, citing his intervention in the case with the six workers.

“In short, a fired Special Counsel is wielding executive power, over the elected Executive’s objection, to halt employment decisions made by other executive agencies,” the administration’s lawyers wrote. “The MSPB, the entity that respondent argues is responsible for supervising him, is deferring to his stay requests so long as the requests are rational. The MSPB, moreover, is being led by a Chairman who has herself been fired by the President, only to be reinstated by a district court. Those developments underscore the grounds for vacating the district court’s order.”

When the justices do eventually take up the case, it will serve not only as a test of their willingness to overturn Humphrey’s Executor — which would give the president unprecedented power over previously independent agencies — but also of their appetite for a broader legal argument that underpins these and other bold moves Trump has made in his second term.

That argument is the “unitary executive theory,” which basically contends that the president has complete power over the executive branch. If he wants to fire government workers, Congress can’t say he can only do so because of issues with their performance. If he wants to fire agency heads, Congress can’t say he can only do so because of “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance.” If an executive branch agency wants to issue a regulation, they better have the president’s approval first.

The president — and the president alone — sits at the top of the executive branch, this theory goes, which means all of the employees in the branch should be answerable to him, and he should be able to fire any of them if he so chooses.

Going back to the earlier graphic, the argument of the unitary executive theory is essentially that any agency in red (even if they’ve traditionally been structured as independent) is part of the executive branch, and therefore the president has full power over them.

Proponents of the theory point to the Executive Vesting Clause of the Constitution, which states that “the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” But critics point to the tradition of separation of powers — as upheld by the Supreme Court in cases like Humphrey’s Executor — as proof that the Framers intended for authority to be split between the branches, even if in occasionally confusing, overlapping ways. The Founding Fathers were terrified of a powerful executive, these critics point out, and explicitly set up the American system so that the president would be limited, even in his own domain.

But supporters of the theory retort that the Framers, terrified as they may have been, still only created one executive, which means they intended for all executive power to ultimately flow in his direction. Article II of the Constitution mentions the president, not the FTC or the Office of the Special Counsel.

The words “unitary executive theory” have never come out of Trump’s lips, but he’s surrounded in his second term by advisers who embrace the philosophy, including Russell Vought, the White House budget director who has called on Trump to adopt a “radical constitutional perspective” in which “the whole notion of an independent agency should be thrown out.”

Last week, the president’s executive order on independent agencies directed them to report their activities to Vought, who in turn reports to Trump. “The Founders created a single President who is alone vested with ‘the executive Power’ and responsibility to ‘take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed,’” a White House fact sheet on the order said, using the exact language of “unitary executive theory” supporters.

The theory has percolated in conservative legal circles for years — and, before that, was essentially advanced by Democrats like FDR — but few presidents have been as aggressive as asserting it as Trump in the last month.

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has sometimes aligned itself with the theory in the past, most notably in their ruling on presidential immunity last year. “The Constitution vests the entirety of the executive power in the President,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his majority opinion in that case. In Trump’s first term, the justices ruled that the prohibition on firings in Humphrey’s Executor didn’t apply to some independent agencies, while keeping it in place for others.

Now, in attempting to fire Dellinger, Trump is asking them to do away with the precedent entirely. After years of daydreaming by conservative lawyers (some of whom now go by “Mr. Justice”), a key contention of the unitary executive theory is about to land before the Supreme Court — paving the way for a potentially major expansion of presidential power.

It will be an outcome almost a century in the making, thanks to a motley crew that includes a long-dead FTC commissioner, a New Deal-era political scientist, and a gaggle of governmental zombies.

I found this very helpful. Thanks for parsing it out in this manner. And I love your "zombie employee" metaphor - completely accurate.

In hindsight, I feel like one of the major mistakes of the Biden years was to embrace the ever-growing power of the executive. But then again, it would take an unusually selfless and farsighted president to limit their own authority.

Anyway, terrific article, Gabe, as always!