Would the GOP Budget Stop Judges From Holding Trump in Contempt?

Diving deep into an obscure but important provision.

In yesterday’s newsletter, I wrote about how a small family-owned company was able to sue the president of the United States and secure a court order blocking his signature policy initiative. (Update: An appeals court temporarily paused that order, allowing the tariffs to remain in effect for now.)

This morning, I want to start off with a recent town hall that was hosted by Rep. Mike Flood, a Republican from Nebraska. You can watch the video below, but it is basically 90 minutes of his constituents lining up to criticize him. America: where you can sue to stop a presidential order and get in a room to yell at your congressman — and he’ll actually stand there and listen. What a beautiful country!

Here’s the very first question that Flood was asked (which starts at around 19:11 in the video):

Q: Can you please tell us why you voted to approve a budget bill that includes Section 70302, which effectively prohibits federal courts from enforcing contempt orders…which would then allow current and future administrations to ignore those contempt orders by removing the enforcement capabilities?

Flood responded by saying that he opposed the section in question. “This provision was unknown to me when I voted for the bill,” he admitted.

I’ve been getting a lot of questions about this provision, which is found on page 544 of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the Republican package to cut taxes, increase defense and border security spending, and reduce the social safety net. Some of those messages have correctly framed the provision. Other’s haven’t.

So, I wanted to write up an explainer this morning, in order to give you a better understanding of a provision you may have seen discussed in the news but might not have all the details of. Plus, as an added benefit, at the end of it, you’ll be able to say you know more about the issue than a U.S. congressman!

As always, let’s start by looking at the text of the provision, so you have a roadmap of where we’re going. Then we’ll take a step back and unpack what it means.

SEC. 70302. RESTRICTION ON ENFORCEMENT.

No court of the United States may enforce a contempt citation for failure to comply with an injunction or temporary restraining order if no security was given when the injunction or order was issued pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(c), whether issued prior to, on, or subsequent to the date of enactment of this section.

OK, now let’s give some background. As you can see, this whole thing hinges on Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(c), itself an obscure provision that you probably haven’t heard of.

To understand 65(c), and why it matters here, I want to start by giving some context on the legal orders that judges have been using when they’ve blocked President Trump’s policies.

Almost all of the orders we’ve seen have not been final rulings on the legal merits of a particular executive action. Our legal system tries to be very thorough, which means it can take a long time to produce that sort of ruling.

But it’s also good to have a way for a judge to stop something from happening in the meantime, to prevent a defendant from taking a certain action while the litigation is ongoing (since sometimes, if the person were to take the action in question, it would be irreversible and the whole case would be rendered moot).

“If there’s a dispute over who owns a tree and somebody wants to cut down the tree,” Notre Dame law professor Samuel Bray told me by way of example, “the court may say, ‘Nobody’s allowed to cut down the tree. I’m going to enjoin you from cutting down the tree until I can decide the case.’ That makes sense, because once somebody cuts it down, it’s over.” (Orders temporarily blocking deportations, to give a higher-profile example, follow a similar logic. Once someone is deported, as we have seen, it can be hard to reverse it, so a court might prevent that from happening until all the legal questions are decided.)

The short-term version of this is called a “temporary restraining order,” or “TRO,” which can last for up to 14 days. After that time, a TRO can be extended — or it can be converted into a longer-term “preliminary injunction,” or “PI,” which does the same thing (temporarily prevent something from happening during litigation) but can last for months or even years.

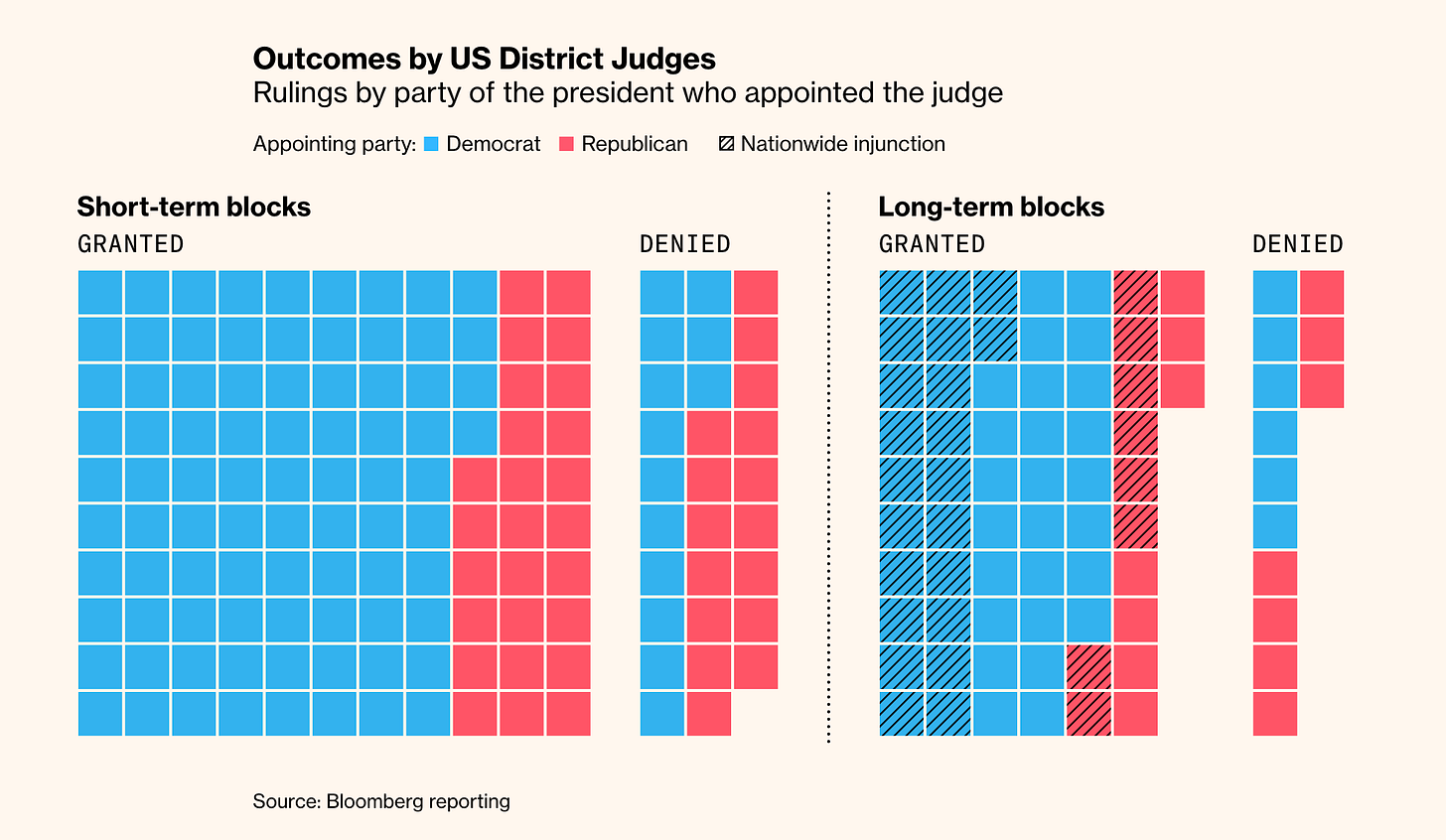

Per Bloomberg, as of May 1, judges had issued 110 temporary restraining orders (presented below as “short-term blocks) and 63 preliminary injunctions (“long-term blocks”) to prevent various Trump administration actions.

The basic rulebook federal courts have to follow in civil cases is known as the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. These are rules the courts set for themselves through the Judicial Conference (the policymaking body of the federal judiciary) and the Supreme Court, although Congress can veto any changes.

There are 87 rules. Rule 65 covers temporary restraining orders and preliminary injunctions. Here’s Rule 65(c):

The court may issue a preliminary injunction or a temporary restraining order only if the movant gives security in an amount that the court considers proper to pay the costs and damages sustained by any party found to have been wrongfully enjoined or restrained. The United States, its officers, and its agencies are not required to give security.

What does that mean? Essentially, if a plaintiff asks for a TRO or a PI, and a court grants it, the court is supposed to ask the plaintiff to put up a certain amount of money in the form of a bond. If it turns out that the TRO or PI was correct, and the action you were suing to stop was illegal, you get that money back. But if it turns out that the injunction was wrong, the defendant gets that money, in order to cover any costs they may have sustained during the period when they had to keep doing (or not do) something even though it turns out the law was on their side all along.

As an example, let’s say the government fires John, and he sues, because John believes he was fired wrongly. The court might grant John a temporary order blocking his firing, and then a month later, a higher court might say that, actually, it was fine to fire him. Should the government have to pay John’s salary for that month, when it turns out they were in the right to fire him? An injunction bond ensures that John, not the government, would be on the hook for that money if he asked for (and received) an injunction even though, in retrospect, he shouldn’t have gotten one.

(Note: Just like when someone posts a bail bond after being arrested, John himself won’t have put up the entire cost of his salary at the outset. He’ll pay something like 1-10% of the cost, and a bond company will pay the rest. Then, if it turns out the injunction was wrongly granted, he’ll have to pay the full amount to the bond company.)

At least, that’s how you would expect this to work from the plain text of Rule 65(c). In reality, courts don’t always ask for injunction bonds — and almost never do when someone is suing the federal government. According to Bray’s research, which examined a sample of 502 preliminary injunctions issued in 2023, only 18% required an injunction bond; in cases involving the government, that number went down to 4%.

“For indigent plaintiffs and for public interest work, especially that’s not well funded, you want to make sure that constitutional rights don’t come with a price tag, and you don’t price people out of being able to vindicate their rights,” Bray told me, “because to get a preliminary injunction, they have to post the bond, and they may not have money to do that.”

This has upset the Trump administration, which has been hit with a lot of these temporary orders, even for some actions which will probably end up proving legal, which means (without injunction bonds) it will have to bear the costs of temporarily paying certain salaries, or funding certain programs, even if final court rulings eventually say they were actually within their rights to try to cancel those expenditures.

Back in March, a presidential memorandum made it the policy of the U.S. government to always request that judges set injunction bonds when plaintiffs sue the Trump administration, in order to avoid this sort of thing from happening. But it’s up to a judge whether or not to set an injunction bond, and judges have mostly ignored the administration’s requests.

“This Court is not bound by the memorandum and declines to adopt any policy that would have the effect of blocking opponents of the government from the courts,” U.S. District Judge Richard Gergel wrote in a recent order temporarily blocking the Trump administration from canceling $31 million in environmental grants.

Gergel added: “The Court thus imposes a nominal bond of zero dollars.”

In other cases, judges have taken the Trump administration up on their requests for an injunction bond, but usually not for the sort of amount they’re seeking. In March, when Judge James Bredar ordered the administration to temporarily reinstate thousands of employees at 18 agencies, he also required the 19 states (plus D.C.) that sued to each pay a $100 injunction bond.

Here’s a photocopy of the actual $100 check that was submitted by the D.C. attorney general’s office:

Suffice it to say, the Trump administration did not feel that $2,000 was enough to cover “the costs and damages” of it having to pay the salaries of thousands of employees who a higher court might eventually say they were able to fire. (Indeed, the circuit court in this case paused Bredar’s order, ruling that the administration was likely to succeed on the merits). The administration made that case to Bredar, but he was not persuaded.

So: all of that context brings us up to the present day. There’s a requirement, Rule 65(c), that isn’t really being followed (whether for a good reason or not is up to you to decide). It’s costing the Trump administration money, and the administration is getting more and frustrated with judges as a result.

This is where the One Big Beautiful Bill comes in. Now that we understand Rule 65(c) and the controversy around it, let’s bring back the text of the proposed provision:

SEC. 70302. RESTRICTION ON ENFORCEMENT.

No court of the United States may enforce a contempt citation for failure to comply with an injunction or temporary restraining order if no security was given when the injunction or order was issued pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(c), whether issued prior to, on, or subsequent to the date of enactment of this section.

Basically, this is an attempt to pressure judges to start actually asking for injunction bonds — and also to pressure plaintiffs to stop asking for nationwide injunctions, another Trump administration bugaboo, which allow an injunction to apply more broadly than to just the plaintiffs in the case. (A fired employee trying to be re-hired might be OK putting up part of their own salary as an injunction bond. But they might think twice before asking for a nationwide injunction, covering any of their ex-colleagues in a similar position, sine suddenly the injunction bond would get quite a bit more expensive.)

But here comes the catch.

If judges don’t issue an injunction bond for a specific order, under this provision, they wouldn’t be able to enforce a contempt citation connected to that order. Contempt citations are the main tool judges use to ensure compliance with their orders: if a judge finds a defendant isn’t following their rulings, they can hold the defendant in contempt, which can then come with a monetary fine or even jail time.

Without the ability to hold people in contempt, courts will have a much harder time enforcing punishments if people flout their orders (unless they start issuing injunction bonds).

Seeing as the provision also prevents contempt citations for injunctions issued without a bond in the past — and judges are examining whether the Trump administration violated such injunctions in at least two separate cases — this could end up having an impact on several live controversies involving the president.

But how much of an impact? Well, the first thing to know about this provision is there’s a pretty solid chance it won’t become law.

The One Big Beautiful Bill is advancing through what’s known as the reconciliation process, which allows majority parties to get around the filibuster, but only if they follow some very specific guidelines. According to the Byrd Rule, you can only use reconciliation for tax-and-spending legislation; you can’t sneak in regular policy changes, unless they have a fiscal component that is more than “merely incidental” to the core of the provision.

It’s an open question whether this provision would meet that bar: while you could certainly argue it would have a fiscal impact (as we’ve seen, whether or not a judge issues an injunction bond can have an impact on the government’s bottom line), you could also argue that the impact is incidental, and not really the focus of the provision.

The Senate parliamentarian gets a first pass at deciding what does and doesn’t comply with the Byrd Rule, but it’s up to a majority of senators to make the final call. (Senators have never overruled the parliamentarian during the reconciliation process, and Republicans have said they won’t this year, but they also sidestepped her advice on a separate matter just last week.)

For the moment, let’s say the provision does get signed into law. It’s difficult to say with certainty what its impact would look like, because the provision is fairly sloppily written. Three issues that have been raised:

The provision says that it apply to any “injunction or temporary restraining order” that didn’t come with a Rule 65(c) injunction bond, even though Rule 65(c) only applies to preliminary injunctions. As written, it would seem that the One Big Beautiful Bill is also preventing contempt citations for final injunctions that lack injunction bonds (which is all of them, since final injunctions are court orders blocking something on the merits once the litigation has come to an end, which obviates the need for a bond). Theoretically, this could wreak havoc on all sorts of old cases, preventing judges from holding parties in contempt for violating final injunctions that have been in place for years. Bray said that would be a likely unconstitutional “intrusion on core judicial power” to enforce their final orders.

There’s a pretty obvious workaround. This new provision says that courts have to issue injunction bonds, but there’s nothing say the injunction bond can’t just be $1 or some other minuscule amount.

The text doesn’t only apply to contempt citations for future injunctions — for which the $1 workaround could easily be imposed — but also to contempt citations for past injunctions for which a judge wouldn’t have known about this provision when they issued their injunction. This could cause some temporary confusion around active temporary injunctions that lacked injunction bonds, but Bray told me that a judge would likely be able to dissolve their existing injunction and issue a new one, just with an injunction bond this time (potentially of only $1), which means the impact would be muted for existing and future injunctions.

Dan Huff, who worked as a lawyer in the first Trump White House and who helped bring Rule 65(c) to the administration’s attention with a Fox News op-ed in February, expressed confidence to me that future drafts of the bill will be amended to solve for Issue #1, clarifying that the provision was only ever intended to address preliminary, not final, injunctions.

“I don’t think that was purposeful,” said Huff, who has been in touch with the White House and the authors of the provision throughout this process. (“Taking away the effect on permanent injunctions would remove the central constitutional problem with the bill as passed by the House,” Bray told me.)

Huff said that he hopes the $1 loophole is also removed, by adding language reinforcing the Rule 65(c) requirement that the injunction bond be an amount “proper to pay the costs and damages sustained.”

However, it would still presumably be up to judges to decide what constitutes a “proper” amount, so that loophole will be hard for Republicans to remove. “It is inevitably discretionary what the amount of the bond is,” Bray said. “I don’t see a way you can reduce that to rule.”

If the change to Issue #1 is made, and if we assume that Issue #3 could be removed by judges simply dissolving their injunctions and creating new ones with a nominal injunction bond, suddenly the impact of the provision would start to shrink.

It might end up pressuring judges to start asking for injunction bonds, which could price some plaintiffs out of temporary relief (though not impact their ability to win permanent relief) or encourage them not to seek such broad relief (perhaps asking on behalf of a more targeted group). But it’s not clear judges’ contempt powers would substantively change, since bonds could simply be set at a low amount (most likely even for existing preliminary injunctions which could be dissolved and re-issued with $1 bonds).

“It will just be a small logistical hurdle or hiccup for the district court judges, because they can just set the bond at $1 and then it will be business as usual,” Bray said.

To Bray, who shares the belief that Rule 65(c) should be used more often, the House provision is a “complete disaster” as written. He agrees that litigants should more often have skin in the game when asking for potentially flawed (and costly) temporary injunctions, but he said the above issues make this provision an ineffective (and potentially unconstitutional) answer to the problem.

“I don’t know of a way to do it specifically,” he said. “But I know this way is terrible.”

If this provision survives the Byrd Rule process (which remains an open question), we’ll see whether any changes are made to address these issues, which could either reduce the provision’s impact (if Issue #1 is fixed) or expand it (if a way around Issue #2 is discovered). Until then, it’s hard to say how much the provision will change in practice.

Excellent, thorough explanation of a seemingly arcane issue that could actually be of great import. Well done as always, Gabe!!

Great explanation--as a lawyer I really appreciate how clearly and succinctly you explain things!