When I Will Call Something a “Constitutional Crisis”

And the two words that Elon Musk will need to learn.

There’s a new mantra that’s been rocketing around the tech world lately: “You can just do things.”

It started as a motivational catchphrase for engineers (“Just do it” for nerds, as one Silicon Valley denizen put it) but has quickly — just like everything from the tech world, it seems — made its way into politics (the right-wing slogan of the Elon Musk era, another writer says).

Conservative radio host Larry O’Connor has called it the “essential” realization of President Trump’s second term.

The first two weeks of Trump’s return have certainly embraced the philosophy, as Musk and his band of Silicon Valley expats have raced to dismantle entire government agencies. (Another techie slogan, “Move fast and break things,” also comes to mind.) But Washington isn’t Silicon Valley, and the president isn’t a tech CEO. There are some things he can “just do” (pardons are a great example), but many more that he cannot.

The original “you can’t just do things” document, of course, is the Constitution, which vests “the executive Power” in a president, but “all legislative Powers” in a Congress.

Admittedly, this can lead to some confusing outcomes. Congress writes laws, and then someone else (the president) is expected to enforce them. The president is the commander-in-chief, but lacks the authority (given to Congress) to declare war. And, most relevantly these days, how exactly can a president boast complete “executive Power” when he needs permission from 535 other people to create, eliminate, or fund agencies in the executive branch?

But the Founders were terrified of tyranny, so this is the system we got. “There can be no liberty where the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person,” James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 47, quoting Montesquieu.

The one big kink in their plan was that Madison and company didn’t foresee that the legislative and executive powers could end up being united in the same party, which incentivizes the two branches to straighten out those overlapping lines of responsibility by simply placing them all under one roof. The executive branch — led by just one person, bolstered by the credibility of a national victory — is the easier place to do this, which has slowly led Congress, as a political party’s junior partner, to be drained of its institutional “ambition” (Federalist No. 51) over several decades, but especially in the last few weeks.

It’s a good thing, then, that the Founders didn’t stop there: such a confusing system needs an umpire, one that will call balls and strikes even when one side of the interbranch competition is contentedly sitting on the sidelines. This is why the Constitution also has an Article III, decreeing that “the judicial Power” shall belong to “one supreme Court,” along with various “inferior Courts” as well.

The first two weeks of Trump’s presidency have been the “you can just do things” chapter, as Congress willingly handed over its power to the executive. But the “you can’t just do things” phase may be coming next, courtesy of the third, oft-neglected branch of government.

While focus (in this newsletter included) has been trained on the legislative branch genuflecting before Trump, less attention has been paid to the moves the judicial branch has already made to rein him in.

In particular, the courts succeeded in producing this little-noticed document — which may seem anodyne, but is perhaps the greatest testament to constitutional vitality we have seen in the Trump era:

The backstory here is that the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued a memo on January 27 directing federal agencies to pause “all Federal financial assistance,” such as grants and loans, as Trump officials reviewed the payments.

On January 28, 22 state attorneys general filed a lawsuit in a Rhode Island-based federal court and asked for a Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) to block the funding freeze. The federal government, as it is supposed to in a case like this, argued that a TRO was not necessary.

On January 30, a federal district judge took the side of the states, granting a TRO and ordering that the government “shall not pause, freeze, impede, block, cancel or terminate” federal assistance to the 22 states. (A judge in a separate case blocked the freeze nationwide.) The judge, as is standard, also ordered the government to “provide written notice of this Order to all Defendants and agencies and their employees, contractors, and grantees.”

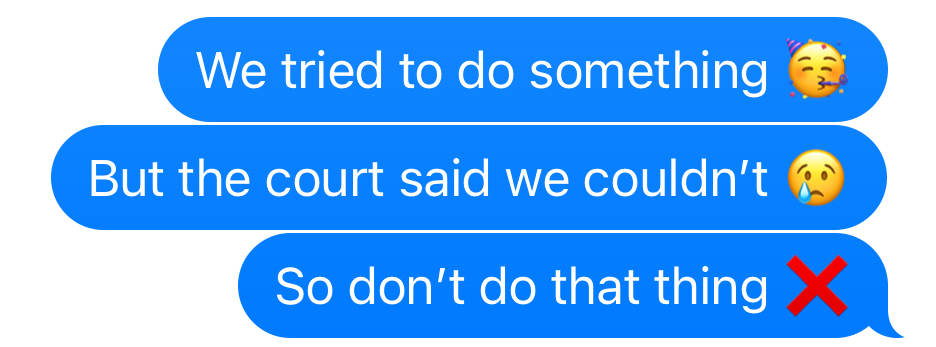

The simple, two-page document above is that written notice, literally called a “Notice of Compliance.” You can read the whole thing for yourself, but I’ll give you the gist right here. Pretend this is the OMB texting federal agencies:

The phrase “constitutional crisis” has been bandied about a lot in the last few days, by lawmakers and journalists alike. I’m usually the person telling others to slow their roll about declarations like that, so I want to lay down my marker now for when you can expect me to adopt that sort of language.

So far in the Trump era, we’ve seen the executive branch trying to aggressively expand its powers. The specific powers are new, but the general trend is not: it is normal for presidents to want as much power as possible. We’ve also seen the legislative branch largely allow these power grabs to happen. Unfortunately, that’s typical as well, disappointing as it may be. Let’s call all that a “constitutional stress test,” and maybe even an urgent one.

To me, a constitutional crisis will arrive when the third branch — the judiciary — steps in to constrain the president’s powers, and the president openly ignores the court order. That’s the makings of a democratic breakdown.

In fact, it’s one of the more common ways for a democracy to fail: it’s pretty risky, when you think about it, to all be playing a game where the umpire has no inherent power and everything is just premised on the players trusting that the other players will do what the umpire says. Courts have no militaries to enforce their will; either the branch with all the tanks listens to what the court has to say, and the system works, or the executive branch laughs in the court’s face, and the system collapses.

As far as I can tell, we haven’t arrived at that point yet — with the “Notice of Compliance” printed above as the best proof, a shining example that the most critical parts of our system are still checking and balancing as they should.

Then again, a notice is just a piece of paper — maybe I’m being too naive. Real compliance requires action, and there is already evidence that the government might not be actively complying with the court’s order. Specifically, 45 Head Start preschools across the country have reported that they are still locked out of the online portal they use to access grant funding, which was shut down during the funding freeze.

Some preschools are having this issue, but not others, so while this is absolutely an important development to watch — some of the preschools might not be able to keep their doors open if the grants don’t come through soon — it seems to me more like evidence of technical errors than intentional non-compliance.

If we ever receive black-and-white proof that the executive branch is refusing to comply with the orders of the judicial branch, that’s when you’ll hear me join the choir of those calling “constitutional crisis.”

In the funding freeze case, the judicial branch moved quickly. But it should be noted that this definition of “constitutional crisis” will require a lot more waiting, as it can take months or even years for cases to wind their way through the courts.

Even if judicial compliance remains intact, this could lead to some cognitive dissonance — as Elon Musk and his deputies race to “move fast and break things” at federal agencies, seemingly unconstitutionally, while the courts are still ten cases behind, methodically hearing arguments.

The executive branch gets a clear head-start in all this, allowing Trump and Musk to constantly be setting a flurry of actions into motion — possibly creating long stretches of intermediate confusion — but, as long as the executive branch continues to follow its orders, the judicial branch will always get the final, clarifying word.

This may make speed seem like a temporary advantage, but ultimately it may prove to be Musk’s undoing.

Another important piece of literature in the federal “you can’t just do things” genre is the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) of 1946, which is effectively the “constitution” for federal agencies. It doesn’t so much lay out what agencies can and cannot do; what the APA really dictates is how they are allowed to do things. Actions have to be taken for a reason, the APA says, those reasons have to be explained, and the public must be given an opportunity to comment on them.

The APA also grants the courts judicial review over agency actions; when conducting that review, courts typically use a test known as the “arbitrary and capricious” standard, which comes straight out of language in the 1946 law.

Elon Musk would be wise to learn these two words. For his, or anyone else’s benefit, I’ve included their Oxford dictionary definitions below:

Arbitrary: Based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system.

Capricious: Given to sudden and unaccountable changes of mood or behavior.

Those sound like pretty good descriptors of how Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has reportedly made its way through the government in the past two weeks. Unfortunately for him, they are also the exact ways that the APA says the government’s cannot operate, and the standards by which courts are supposed to judge executive actions. The government, it turns out, has a literal rule against moving fast and breaking things.

Every presidential administration tries to move too quickly — although perhaps none as much as this one — and then eventually runs into the APA. Trump’s first administration was no exception: while the government typically wins about 70% of cases brought under the APA, according to the Washington Post, Trump lost 78% of such cases in his first term, an NYU database records. And that was before DOGE poked its nose into things.

The “arbitrary and capricious” rule is what doomed Trump’s Muslim ban, his attempt to undo the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, and many other initiatives. And, yes, before you ask: Trump does benefit from the fact that he appointed one-third of the Supreme Court, who will be the ultimate arbiters of arbitrariness. But the court wasn’t exactly shy about rebuking him in his first go-around: according to data by two USC professors, Trump’s SCOTUS “win rate” (43.5%) was lower than any president in the post-World War II era. Trump followed the court’s decisions every time.

Ironically, in his second term, Trump could find his life made even harder by a decision of the very 6-3 court he did so much to build. The court’s opinion in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, issued last year, strengthened the ability of courts to strike down actions that are being reviewed under the APA, ending the decades-long Chevron precedent that encouraged courts to give deference to federal agencies in such cases.

The original Chevron decision, in 1984, was handed down by a conservative court, as a way to allow the Reagan administration to take (in his case, largely deregulatory) actions without facing heightened legal scrutiny. But it soon became a bête noire for conservative activists, as it allowed successive Democratic administrations to more easily implement regulations. In one final twist of fate, it was finally undone in Loper Bright, just before a Republican president was about to enter office, when he could have benefitted from the same ease of deregulation Chevron accorded to Reagan.

Now — due to a decision made possible by his three appointees — Trump could find his administrative actions facing even more hurdles in the courts.

A stack of lawsuits have already been filed, meaning attention is about to shift to the judicial arena as courts begin considering the legality of Trump’s (and Musk’s) actions. Many of the suits, as is typical for administrative challenges, cite the APA.

The lawsuit against the funding freeze charged that the administration’s failure to “acknowledge [its] catastrophic practical consequences” or to “provide a reasonable explanation why those consequences could possibly be warranted” qualified the move as “arbitrary and capricious.”

Two challenges to Trump’s “Schedule F” order argue that his administration did not properly follow the steps to undo a regulation, failing to issue a public notice or offer a comment period, as the 1946 law requires.

“Under the APA, agencies cannot depart from prior policies without acknowledging that they are making such a change and explaining their reasoning for doing so,” reads a lawsuit against the Trump administration’s policy change to allow immigration enforcement at schools and churches. “In undoing decades of prior agency policy without reasoning, DHS engaged in arbitrary and capricious agency action.”

As in Trump’s first administration, many of the lawsuits use the flip-flops of the president and his deputies against them: a tweet by Karoline Leavitt has become a key piece of evidence in the legal fight over the funding freeze; the “conflicting information” offered by DOGE employees about the so-called federal “buyout” offer was cited in a lawsuit to prove the capriciousness of the initiative.

The president can do some things, but moving slow and judiciously is actually the best course of action to achieve maximum results, since that’s what the APA requires. Elon Musk appears to have missed that lesson in his civics crash course.

Already, in addition to the funding freeze, two federal judges have paused Trump’s birthright citizenship order; another has blocked the administration’s move to transfer transgender inmates. (Several of the judges have been Biden appointees, a reminder that in the judicial branch, “elections have consequences” can apply to previous elections as well — and that liberals who spent the past four years railing against judicial lifetime tenure may yet come to appreciate it.) Other lawsuits await on everything from Trump’s efforts to purge the FBI to Musk’s intervention into the Treasury Department payments system to the existence of DOGE itself.

It is unlikely that any legal challenges will be brought stemming from Trump’s comments last night about taking over Gaza — partially because it is unlikely that any actions will stem from the remarks. “You can just say things,” Elon Musk has tweeted, a fitting spin on the popular mantra. True enough. But doing things is entirely another matter.

Trump and Musk will doubtlessly be frustrated if laws like the APA constrains their actions, but the truth is, they really would have liked its author.

Just like how other laws Trump is battling grew out of the Watergate scandal, the APA was an effort to restore balance after another era of expansive presidential power: the New Deal. The bill was sponsored by Nevada Sen. Pat McCarran, who frequently battled with FDR, his fellow Democrat.

McCarran proudly called the APA a “bill of rights for the hundreds of thousands of Americans” — make that hundreds of millions — “whose affairs are controlled or regulated” by federal agencies.

In a speech before its passage, he also described it as “one of the most important measures that has been presented to the Congress of the United States in its history.” Why? McCarran explained:

We have set up a fourth order in the tripartite plan of Government which was initiated by the founding fathers of our democracy. They set up the executive, the legislative, and the judicial branches; but since that time we have set up a fourth dimension, if I may so term it, which is now popularly known as administrative in nature. So we have the legislative, the executive, the judicial, and the administrative.

Sounds positively Muskian: just substitute “fourth order” for the “deep state.”

But Musk cannot have it both ways. Just as he rails against the rule of unelected bureaucrats, despite being one as well, he is now trying to curb executive overreach by seemingly engaging in some himself. But the APA makes no distinction between executive actions intended to shrink or expand executive power — both kinds fall under its jurisdiction.

If Musk was willing to move slowly, laws like the APA offer an exact guidebook for how he can go about shrinking the executive branch (that was, after all, the law’s original purpose). But there is a process that must be followed. If Musk insists on moving fast and breaking things, that process will rear its head in the form of black-robed umpires. The question then will be whether the world’s richest man sees fit to follow their orders.

Well written piece.

However, I notice that you did not mention at all - unless I missed it & if I did, do correct me - the impact that “…possibly creating long stretches of intermediate confusion…” will have on individual lives. Millions of individual lives.

Do you realize that musk’s “…intermediate confusion…” tactics are taking away money that people need to live their lives? That once the South African Nazi and his equally traitorous underlings start halting Social Security payments, Medicare & Medicaid benefits and veterans benefits and payments, people’s actual lives will be severely impacted? As in immediately. What are they supposed to do while all these lawsuits work their way through our lopsided court system? What are they supposed to eat? Where will they live once they can’t pay their mortgage or rent and they are evicted? All of these things will begin to happen while we are all sitting around waiting for lawsuits to be filed and judges to act.

Has anyone at all considered this - why is musk being allowed to take over government departments? Do you know what would have happened to me if I had ever showed up at the Treasure Dept, walked in, sat down at a desk and started typing away, breaking into the systems and making changes? How long before I was wearing handcuffs? How long before my ass was in a jail cell for the duration after being denied bail? Shouldn’t this have happened right away? Why didn’t it?

Are the federal marshals and DC police too afraid to do their jobs or are they all in trump’s pocket already? It certainly seems so.

Why isn’t anyone asking these questions?

I won’t find any comfort at all in knowing a lawsuit to return my veteran’s disability and healthcare is winding its way through courts while my cat and I try to survive while living in my car after losing my home. And what if the far-right Supreme Court rules in trump & musk’s favor - which is entirely likely. What then?

Very well written. That said you have more faith in SCOTUS to do the right thing than I do.