When Giants Walked the Halls of Congress

Are lawmakers happy with how they’re spending their time?

I. Deleted

If congressional powers that they rarely use are deleted from the internet, does it make a sound?

Earlier this week, users on the online forum Lemmy noticed that multiple sections of of the Constitution had quietly been scrubbed from the Library of Congress website, which maintains an annotated version of the document.

The Library of Congress rushed to correct the deletion, which they attributed to a “coding error.” On Lemmy, the user who first discovered the mishap speculated that it could be a “ham-handed way to announce an additional step towards dictatorship, which are now being walked back as too outrageous, using a the pretext of a coding error as a way to save face.”

I very much doubt that that’s the case; the sections of the Constitution that appear on the Library of Congress website has no bearing on the sections of the Constitution that remain in effect. But the incident gives us reason to consider some of the parts of our founding charter that were briefly cast off into the digital void.

Among the provisions that disappeared: Article I, Section 8, Clause 18, which gives Congress the power to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers [which are listed in previous clauses, some of which were also deleted], and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”

This is sometimes known as the “Elastic Clause,” because it allows Congress to stretch its powers so widely, to include almost anything lawmakers view as “necessary and proper” to legislate. The Framers viewed it as a sweeping grant of power to the branch of government they expected to predominate; a pair of scholars once said it “just might be the single most important provision in the Constitution.”

But today, if it was removed from the Constitution — in real life, not just in pixel form — would anyone notice? After all, Congress hasn’t been doing much to take advantage of its overwhelming powers lately. The Elastic Clause has been looking pretty skinny.

II. The Purse

Helpful proof of this fact came late last month, when a group of Republican lawmakers celebrated a big victory.

Sen. Jim Justice (R-WV) boasted in a statement: “Promising to protect West Virginians’ best interests is why I was elected, and results like this show what can happen when you work in good faith with others across government and put people over politics.”

What was the result Justice was bragging about? What shiny new law had he gotten passed to help his constituents.

Let’s go to the next line of the statement. “The release of these funds will undoubtedly have a positive impact on the kids of West Virginia, and I’ll continue to advocate with Senator Capito for the best possible outcomes when problems like this arise,” Justice added. (Emphasis mine.)

What Justice was celebrating wasn’t a new piece of legislation. It was the fact that he and other Republican lawmakers had successfully persuaded the Education Department to release $6 billion in grant money — funds that Congress had already approved — that the Trump administration had been declining to spend.

“We write to ask you to faithfully implement the Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 Full-Year Continuing Resolution Act, which President Trump signed into law earlier this year, including the education formula funds that states anticipated receiving on July 1, 2025,” Justice and his colleagues had written in a letter the week before.

There is a lot of this going around lately. Last week, Justice joined another bipartisan letter, asking the Trump administration to release $324 million that was appropriated to the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund as part of the Trump-signed continuing resolution (CR). The day before, a group of Republicans penned a letter asking for the release of funds appropriated to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“Suspension of these appropriated funds — whether formally withheld or functionally delayed — could threaten Americans’ ability to access better treatments and limit our nation’s leadership in biomedical science,” the senators wrote.

On Tuesday, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), Congress’ in-house auditor, concluded that the Trump administration’s failure to disburse NIH funds constituted a violation of the Impoundment Control Act (ICA) of 1974, which prevents presidents from unilaterally refusing to spend congressionally appropriated funds.

In their letter, the GOP senators who urged the administration to spend the appropriated money did not raise any of these legal questions or threaten to investigate. “We respectfully request that you ensure the timely release of all FY25 NIH appropriations in accordance with congressional intent,” they asked politely.

The GAO has accused the Trump administration of violating the ICA by illegally holding up funds on several other occasions, in regards to electric vehicle charging stations, library funds, and Head Start. The agency has opened at least 40 other investigations into the administration. Republican lawmakers have said almost nothing about the findings that the administration is breaking the law by holding up funds they themselves appropriated.

When you consider how much the job of serving in Congress is shrinking — from wielding the power of the purse to wielding, seemingly, only the power to ask for the purse — it’s hardly a surprise that fewer prominent politicians want to do it.

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) announced yesterday that she is leaving her seat in Congress to run for governor of Tennessee. She is the third sitting senator to mount a gubernatorial run this year, following Sens. Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Tommy Tuberville (R-AL). Meanwhile, only one former or sitting governor is currently running for Senate, former Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC).

To our modern ears, that makes perfect sense. Who wouldn’t rather serve as a chief executive, actually implementing an agenda, rather than as one of 100, reduced to begging for the money you already voted for to eventually be spent?

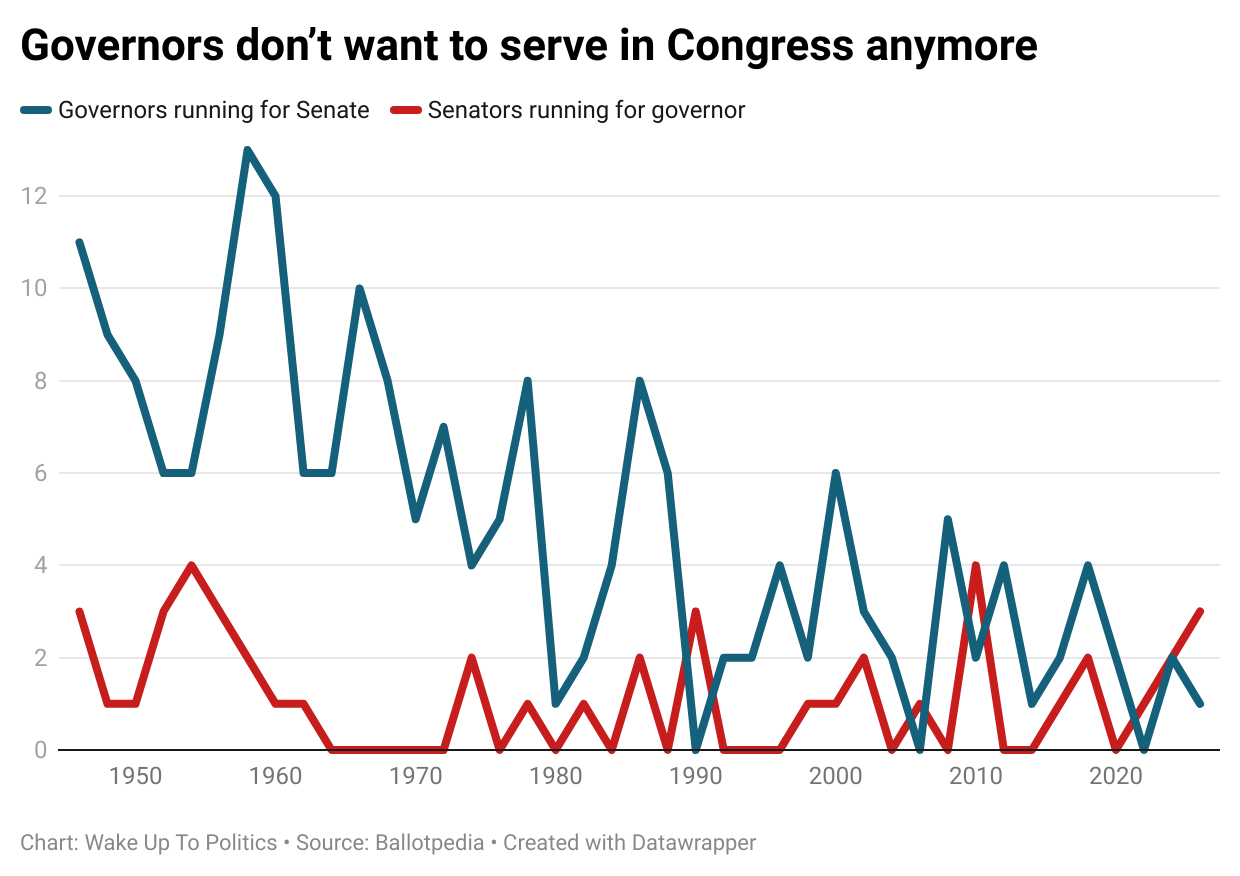

But, historically, this is an anomaly. As the below chart shows, using data from Ballotpedia, this is shaping up to be only the third election cycle since World War II in which more sitting or former senators are running for governor rather than the reverse. In fact, in years past, it wasn’t unusual for zero senators to give up their seats to run for governor. Meanwhile, as recently as the 1970s and ’80s, as many as eight governors would regularly mount campaigns to serve in Congress. There has been a stark decline since then.

Jim Justice himself, the senator who joined letters asking the Trump administration to release the Education Department and CDFI funds, is a former governor. It’s possible that more governors will announce Senate runs in the coming months, changing the above chart. But, if they’ve seen how Justice is forced to spend his time now that he’s out of the governor’s mansion, why would they want to?

Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) admitted to Punchbowl News that the flow of senators leaving to chase governorships makes it harder to persuade governors that their talents are worth taking to the Senate. “Yeah, that’s a little hard to explain,” he said.

III. Entrepreneurs

All of this was on my mind while I was researching a column I wrote this week for the Preamble newsletter. The piece was about discharge petitions, the procedural tool that allows rank-and-file lawmakers to force a vote on a bill on the House floor if a majority of House members (218) sign on.

I wanted to find out what the first bill was to become law using the discharge petition process. As it turned out, it wasn’t a minor measure: it was the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), the 1938 bill that instituted America’s first federal minimum wage ($0.25 an hour), as well as codifying the 40-hour work week (with guaranteed overtime pay for certain workers) and prohibiting “oppressive” child labor.

The FLSA, I learned, was sponsored by a New Jersey congresswoman named Mary Norton.

Norton entered politics by accident, inspired by tragedy. “When my only child, a son, died in infancy, the bottom dropped out of my world for a time,” she later said. With her grief, Norton resolved to do something to care for children, which led to her helping start a day-care center in the basement of a church. That work brought her into contact with the mayor of Jersey City, who eventually persuaded her to run for the New Jersey Democratic State Committee, and then for the Hudson County Board of Freeholders, and eventually for Congress.

She was the first Democratic woman elected to Congress in U.S. history. She also became the first woman to chair a major congressional committee, which caused some discomfort here in Washington. “This is the first time in my life I have been controlled by a woman,” one member of the panel said.

“It’s the first time I’ve had the privilege of presiding over a body of men,” Norton replied, “and I rather like the prospect.”

As chair of the Labor Committee, she managed the process for the Fair Labor Standards Act. When the measure was repeatedly blocked in the Rules Committee, which was then controlled by a coalition of southern Democrats and conservative Republicans, Norton came up with the strategy to jam the bill onto the floor with a discharge petition.

She recruited key allies, including writing a pointed telegram to Franklin Roosevelt, reminding him of his pledge to support a minimum wage. (Roosevelt’s response to Norton endorsed her discharge petition proposal.) Norton was persistent in perusading her colleagues to back the petition and even convinced some of them to return to Washington in order to sign.

When Norton was ready to bring her petition to the House floor — with her name affixed as the first signature — so many congressmen crowded around it, ready to sign, that the speaker of the House had to beg them to form a single-file line. According to a Time magazine report, up to that point, no discharge petition had ever received more than 100 signatures in a single day. In less than two and a half hours, Norton notched all 218 she needed. (The report notes that one congresswoman had flown in from Indiana to sign, at Norton’s urging, but once she returned to Washington, she found that the petition’s signatures had already been filled up.)

The FLSA soon passed the House and then the Senate, and was ultimately signed into law by FDR. Because of Norton’s dogged advocacy, America had a national minimum wage for the first time.

When I was first reading Norton’s story, I was surprised I had never heard of her before. I like to think that I have a pretty good handle on the major lawmakers of the 20th century.

But, the truth is, the bar for being a “major lawmaker” back then was much lower. Norton never served as speaker of the House or House majority leader. In fact, her greatest legislative accomplishment came as a result of bucking congressional leadership, which is incredibly rare today.

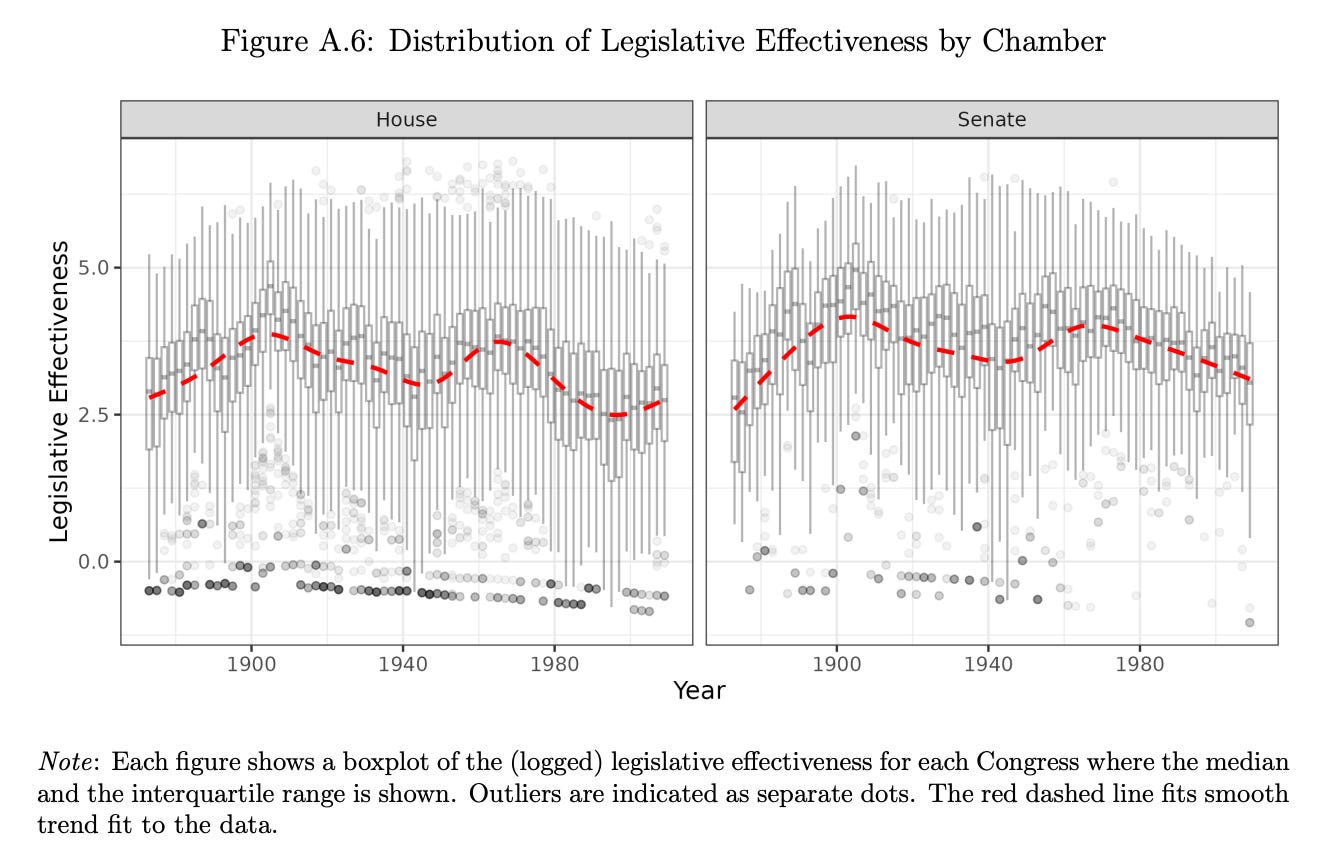

Power in Congress was much more diffuse, which meant more rank-and-file lawmakers — especially committee chairs, like Norton — had enough sway to advance causes they believed in, even if their party leaders were hesitant to get on board. Norton was a classic “legislative entrepreneur,” somebody who worked within the system to find creative ways to advance her agenda, even if it required freelancing. Congress used to have many more Mary Nortons, entrepreneurial lawmakers who left a mark on public policy even if they never spent a day in a leadership office.

This change can be tracked empirically, as in this chart by a pair of scholars who calculated the “legislative effectiveness” of every member of Congress since the 1870s (based on how many bills they introduced, with bills deemed notable receiving extra points). A stark decline is evident in recent decades:

Compare Norton’s track record — which included the enactment of major bills impacting labor, women, and home rule in Washington, D.C. — to those of the senators now decamping to run for governor.

In 16 years in Congress, Michael Bennet (D-CO) has sponsored exactly one bill that became law, on revising the federal charter of Blue Star Mothers of America, Inc. Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) has written one law in five years, on life insurance for veterans. In 22 years, Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) has authored seven, five of which revolve around federal building renamings and historic battlefields.

Sponsoring a bill is not the only way to make a difference as a member of Congress: this list does not reflect bills a member co-sponsored, or bills that may have been enacted as part of other laws, or issues championed at the committee level.

But it is still worth asking whether today’s lawmakers are satisfied with what will go on their congressional epitaphs, the final accounting of the public policies they used their lofty offices to write. When they exit Congress, fewer and fewer lawmakers have notable pieces of legislation they can point to. Are there many who can match the output of the giants who once served in Congress, jealously protecting their turf and doggedly working to turn bills into laws? “He persuaded the executive branch to spend the money it legally had to spend” isn’t exactly a great career summary.

Congress is suffering from a severe lack of Mary Nortons, legislative entrepreneurs who are willing to buck their party and unearth creative avenues in order to make law.

I want to dig Mary Norton up and hitch her up to a strong electric battery and shock her back into life. We need that woman.

Yes, I have the impression that giants once walked the Halls of Congress. I also have the impression that smaller giants faithfully attended the voting booth. Both are probably nostalgia on my part. But I have almost NO faith in the folks that walk the Halls of Congress now. You are so refreshing Gabe. THank you and keep it up !