What Happens in a Shutdown?

Plus: What it was like inside the Senate chamber as the deadline neared.

Welcome to the 2025 Government Shutdown, Day 1.

Last night, the Senate held two votes:

One on the House-passed, Republican stopgap measure, which would keep the government open through November 21, holding funding levels constant except for a $88 million boost to fund security for government officials;

And the other on a Democratic alternative, which would keep the government open through October 31, while also permanently extending the enhanced Obamacare premium tax credit, repealing recent Medicaid cuts, restoring funding to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and limiting the Trump administration’s ability to enact rescissions.

Both measures failed to reach the 60 votes they needed to pass. The vote on the GOP bill was 55-45, with support from three Democrats and opposition from one Republican. The Democratic bill failed 47-53, along party lines.

That was around 7:25 p.m. Then, everyone went home. There were no late-night negotiations or last-minute rescue attempt. At 11:59 p.m., government funding expired and a shutdown began a minute later. Here is the official status update from the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, the government’s HR office:

I was inside the Senate chamber last night for the final votes; I’ll have more for you on what I saw below. But first: We haven’t had one of these in more than six years — since the 2018-19 shutdown, which lasted 35 days, the longest in history — so I thought we’d start with a refresher on what exactly happens when the government runs out of money.

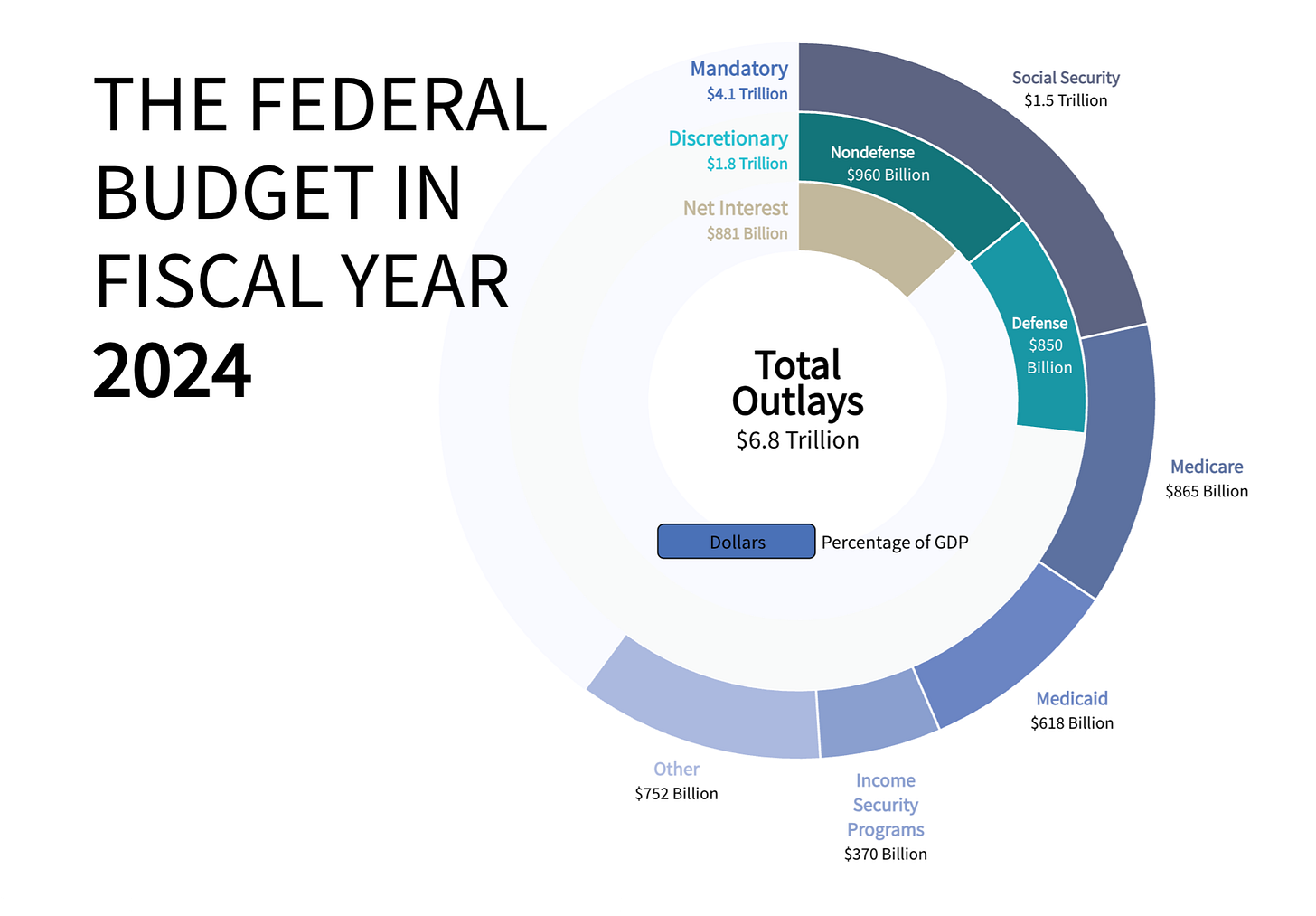

Well, that’s imprecise. The government never actually runs out of money, not really. As of this week, it has about $805 billion in its checking account. That cash doesn’t just disappear in a shutdown. And not just that: a lot of it continues being spent! In fact, 60% of government spending is “mandatory,” which means it doesn’t rely on yearly appropriations bills by Congress.

So those funds aren’t affected by the legislature’s failure to pass a funding measure: that means Social Security checks and Medicare payments will carry on as normal. (Medicaid is also classified as mandatory spending, but it actually is funded by the annual appropriations process. However, the most recent spending bill funded the program through the end of 2025, which means Medicaid will only be affected by the shutdown if it lasts for three whole months.)

Another 13% of federal spending is interest payments on the national debt: those keep going, too.

So, we’re really talking about the last 27% or so of federal spending, the funds designated as “discretionary.” The money that was supposed to go to these programs doesn’t evaporate either — but Congress has to tell the Treasury how to spend this money each year, which it does through the appropriations process. Without appropriations bills, the government doesn’t know what it’s supposed to do with these hundreds of billions of dollars.

For most of American history, though, the government kind of ignored that. When appropriations lapsed, agencies would largely continue operating, the modern equivalent of what happens when Congress passes a continuing resolution (CR) holding existing funding levels constant (though, in these cases, Congress hadn’t passed one).

That changed during the Carter administration in 1980, when then-Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti unveiled a new interpretation of the Antideficiency Act of 1870, which prohibits the government from spending “any sum in excess of appropriations made by Congress.” Civiletti’s reading of the law — which remains in force to this day, though theoretically the Attorney General could always revert to the pre-1980 interpretation — was that without appropriations bills in effect, discretionary government programs had to cease operations.

The next year, following pushback from the Carter White House, Civiletti released a new memo that outlined some exceptions, most notably that government operations involving “the safety of human life or the protection of property” could continue. That’s why each agency has their own shutdown contingency plan, deeming employees either “essential” (they keep working in a shutdown, but without pay) or “non-essential” (they are “furloughed”).

I’ve spent the last 24 hours leafing through a lot of these plans — and the good news is that most of the government operations you probably recognize are seen as “essential” and will continue. The military continues to serve. The Postal Service is mostly self-funded, so mail will keep being delivered. Immigration enforcement will carry on; so will passport services. Open-air national parks will stay open, though staff will be limited and most visitor services will stop.

Air traffic controllers and TSA agents are “essential” too, though in past shutdowns, some have called in sick rather than working without pay, which can cause travel delays or cancellations.

A lot of agencies try to find ways to keep working by relying on pots of money that don’t come from the appropriations. The IRS, for example, says it has enough mandatory funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to avoid furloughs for at least five days. The Smithsonian museums say they have enough money lying around to stay open at least until Monday.

In past shutdowns, the federal courts have relied on funds like court fees to stay open; this year, the judiciary says they have less on hand usual and are only sure that they’ll be able to maintain full operations through Friday. Once their existing funds run out, the courts will be “limited to activities needed to support the exercise of the Judiciary’s constitutional functions and to address emergency circumstances.”

The Justice Department carries on with criminal litigation during a shutdown (unless the courts shrink operations, of course), but civil litigation is mostly postponed. (As Politico’s Josh Gerstein flags, the Trump administration is already filing motions to pause civil cases against the government during the shutdown, like this lawsuit over domestic violence and homelessness grants that were terminated).

Still, when you read over the shutdown plans, you’re also reminded of a whole universe of government operations that you might not think of in your day-to-day life, some of which are put on pause during a shutdown.

The Education Department, Small Business Administration, and National Science Foundation stop issuing new grants. The NIH continues to care for patients at its hospital, but it will only admit new patients if strictly “medically necessary.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics shuts down completely, which means the September jobs report that was supposed to be released on Friday won’t go out.

According to the CDC’s plan, it won’t be able to “provide communication to the American public about important health-related information,” “analysis of surveillance data for reportable diseases [will] be suspended,” and no guidance will be given to states on “implementing programs to protect the public’s health (e.g., opioid overdose prevention, HIV prevention, diabetes prevention).” That doesn’t sound great.

The FDA plan says that its Animal Drugs and Foods Program will “end pre-market safety reviews of novel animal food ingredients for livestock,” which will make it “unable to ensure that the meat, milk, and eggs of livestock are safe for people to eat.” That really doesn’t sound great! (The agency did add that anything involving “imminent threats to the safety of human life” will continue.)

A Veterans Affairs program that helps veterans and their families transition to civilian life will be put on hold. The Transportation Department says that it will stop research, special investigations, and training relating to the nearly 1 million shipments of hazardous materials sent around the U.S. every day (though, again, “imminent hazards” will continue to be addressed).

The U.S. government is an enormous machine, mostly laboring in the background of our lives. Many of the most visible parts keep humming during a shutdown, but there are all sorts of less-heralded programs that will either stop or be sanded down. (All of these plans are subject to change; traditionally, the executive branch decides what is and isn’t “essential,” and these determinations can change — in either direction — as the shutdown continues.)

And, of course, more than 3 million Americans will be denied their paychecks — including around 2 million members of the military and roughly 700,000 civilian federal employees who will be expected to continue working without pay, plus about 750,000 workers who will be furloughed.

Under the Government Employee Fair Treatment Act of 2019, which was passed after the last shutdown, all of these workers will be given backpay as soon as the shutdown ends. That means, according to the Congressional Budget Office, for every day the shutdown continues, the government will owe an additional $400 million in backpay to workers who didn’t come in to work. (This isn’t those workers’ fault, of course! But it illustrates how shutdowns are a raw deal for the American taxpayer, who foot the bill and get nothing in return.)

The CBO estimated that the 35-day shutdown in 2018-19 caused $3 billion in losses for the American economy that were never recovered.

The Trump administration is also threatening to use the shutdown to lay off more federal workers permanently, which is known as Reductions in Force (RIFs). As I noted in March, there is an interpretation of the RIF regulations — promoted by some Trump allies — that would suggest a shutdown unlocks an easier and faster way to carry out the layoffs. As best I can tell, the administration has not embraced this interpretation, which means it is merely using the shutdown as a pretext to carry out more RIFs, rather than asserting that the funding lapse gives them added power to do so. (Unsurprisingly, the employees who carry out RIFs have themselves been deemed “essential.”)

“We can do things during the shutdown that are irreversible that are bad for them,” President Trump said yesterday, referring to Democrats.

One group of people that continue to be paid during a shutdown are members of Congress: the 27th Amendment guarantees that nothing, not even a shutdown, can adjust a sitting lawmaker’s salary.

Perhaps that explains the mood inside the Senate yesterday, when I was there in the press gallery watching the CR votes. I’m not sure precisely what I was expecting in the hours before a shutdown was about to commence, but I found the vibe to be strangely … unbothered?

During the back-to-back votes, senators milled around like normal, chatting and laughing with each other. Instead of partisan animosity, there was actually quite a bit of talking across the aisle. (Not that they seemed to be talking about funding bills or workers going without salaries based on their facial expressions, though I couldn’t hear their words exactly.) Sens. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) were engrossed in conversation for quite a while; so were Sens. Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN). Cruz appeared to be showing Klobuchar photos on his phone.

The Senate floor is one of the few workplaces where you’re watched like a hawk the whole time you’re there — and several lawmakers hammed it up for their audiences. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) waved animatedly to a group of schoolchildren sitting in the gallery; when members of the public laughed as Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) jammed his thumb down rather emphatically while voting on the Democratic CR, he entertained them by doing it again and again.

Between the two votes, Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) and Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) each delivered short speeches — and this was the only time everyone snapped into place and played their roles, flashing a brief acknowledgement that they weren’t just casting a run-of-the-mill vote but were putting a halt to parts of the federal government.

Still, Schumer gave a knowing smile as the Republican side of the room laughed when he bashed a New York Times poll as “biased”; later, Thune acknowledged that Schumer had borrowed one of his charts earlier. Schumer flashed a thumbs up in response.

And, then, after condemning each other a bit, life went on. Senators sauntered up to the rostrum, glanced at a piece of paper to confirm which bill was being considered — “How should I vote?” Mississippi Sen. Roger Wicker, 74, could be heard asking at one point — and casually stuck their thumbs up or down to indicate their votes. On both sides of the aisle (and in cross-party conversations), senators clapped each on the backs and chatted amiably.

It’s not as if I was expecting a negotiation to break out right there on the floor, but I was struck by the fact that the senators didn’t even seem fazed by the shutdown they were about to initiate (at least until the speeches started). Notably, two senators who didn’t interact were Thune and Schumer, although their desks are stationed right by each other (only separate by an aisle). Reportedly, they’ve barely been on speaking terms of late.

When it came time for a vote on the House-passed CR — the final chance to avert a shutdown — Schumer suffered three defections: Democratic Sens. Catherine Cortez Masto (NV) and John Fetterman (PA), plus Angus King, a Maine Independent who caucuses with the Democrats.

Several other Democrats seemed to be wavering. Senate Appropriations Committee ranking member Patty Murray (D-WA) spoke to Sens. Maggie Hassan and Jeanne Shaheen, both New Hampshire Democrats, for a long time before they cast their “nay” votes. Other members appeared to be working on Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) in a similar fashion.

Like Cortez Masto, Fetterman, and King, Gillibrand, Hassan, and Shaheen all voted for a CR in March that was opposed by most Senate Democrats; if they flip at some point during the shutdown, the CR will have notched 58 votes, two away from passage (assuming that Kentucky Republican Sen. Rand Paul remains in the “nay” column). The other Democrats who supported a CR in March are Gary Peters (D-MI) and then Schumer and his top deputies, Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Brian Schatz (D-HI).

For the moment — with those exceptions — senators on both sides seemed resolved, to the extent they even seemed particularly focused on the votes in front of them. The chamber is set to go through the same ritual today, voting again on both CRs. Thune has said he will continue scheduling those votes for as long as it takes to end the shutdown.

It seems like our representatives don't represent their constituents earnestly and honestly, just one upmanship games for control of an imaginary chessboard.

Great explainer and interesting reporting.

I'm struck by how contrived the whole shutdown process is. If lapsed appropriations actually means something it should be affecting the entire goverment, not just 1/4 or less of it. If it doesn't, what are we even doing here? Given the complete arbitariness of what gets counted as essential or not, the pre-1980 interpretation seems much more logical to me.

All the current process does is give the minority party a cudgel to destroy an enormous amout of wealth and productivity, a cudgel Republicans have been more than happy to use out of spite in the past and now Dems are coming around to using as well. The whole process just seems insanely stupid and wasteful to me.

The lack of urgency is probably because so much of the government isn't shutting down. It's easy to look at all of the services and payments still continuing and discount the millions of people who are going without pay and services for an unknown amount of time. If a shutdown *really* meant a full government shut down I think both sides would care a lot more about avoiding one.