Two Things Americans Agree On

Murder bad. Speech good.

Has anyone heard from Brendan Carr lately?

Exactly three weeks ago, the head of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was appearing on a right-wing podcast, decrying ABC late-night host Jimmy Kimmel’s comments about Charlie Kirk’s killing as “some of the sickest conduct possible.”

He explicitly threatened to revoke the broadcast licenses of ABC affiliates that continued to air Kimmel’s show. “We can do this the easy way or the hard way,” Carr added. “These companies can find ways to change conduct and take action, frankly, on Kimmel or, you know, there’s gonna be additional work for the FCC ahead.”

Carr briefly got his “easy way.” Hours after he made his threat, Sinclair and Nexstar — the two largest owners of ABC affiliates, both of which require FCC approval when they execute mergers — announced plans to preempt Kimmel’s show on their stations for the foreseeable future. Shortly thereafter, ABC announced that Kimmel would be indefinitely suspended.

As it turned out, the suspension lasted just six days. By the next week, Kimmel was back on the air. At first, Sinclair and Nexstar continued to preempt his program; however, that too only lasted a few more days.

You might think it would be time for the “hard way,” then: Kimmel’s show is airing every night, despite his comments about Kirk, the exact scenario in which Carr said he would look into pulling broadcast licenses. Why isn’t the FCC chair following through?

Well, there’s one part of the story I left out.

During Kimmel’s suspension, a number of unlikely voices emerged to defend the left-leaning comedian from Carr: Republican senators. “What [Carr] said there is dangerous as hell,” Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) said on his own podcast, comparing the FCC chair’s comments to a “a mafioso coming into a bar going, ‘Nice bar you have here, it’d be a shame if something happened to it.’”

“I think it is unbelievably dangerous for government to put itself in the position of saying, ‘We’re going to decide what speech we like and what we don’t, and we’re going to threaten to take you off the air if we don’t like what you’re saying,’” Cruz added. “And it might feel good right now to threaten Jimmy Kimmel, but when it is used to silence every conservative in America, we will regret it.”

Cruz’s comments opened the floodgates: he was soon joined by Mitch McConnell, Dave McCormick, Rand Paul, Todd Young, and other Republican senators who criticized Carr’s threat.

I think this chain of events is worth highlighting for three reasons: First, it is one of the most significant examples since Trump returned to office of a considerable number of Republican lawmakers — from across the party’s ideological spectrum — speaking up to say that they felt an action by the Trump administration went too far.

Second, when such an outcry did take place: it worked. We shouldn’t let this episode pass without noting that Carr made a big threat, was slammed for it by fellow Republicans, and now that he isn’t getting his way on Kimmel, there is no evidence that he plans to follow through. Carr backed down under pressure. TAOACO: Trump Administration Officials Always Chicken Out?

But, finally, I also think the experience of the last month since Charlie Kirk was gunned down in Utah has taught us something valuable: if nothing else, there are two big things Americans agree on — we oppose political violence and we support free speech.

Let me prove it to you.

We oppose political violence.

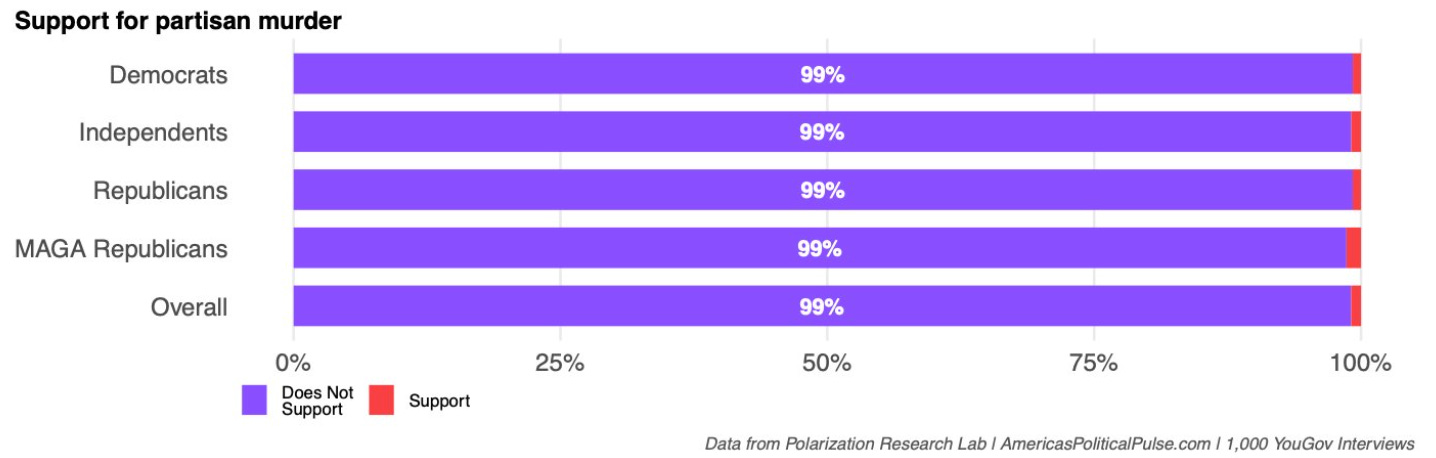

There are many surveys that attempt to quantify support for political violence, but I think the Polarization Research Lab — led by Dartmouth political scientist Sean Westwood — offers a helpful bank of research.

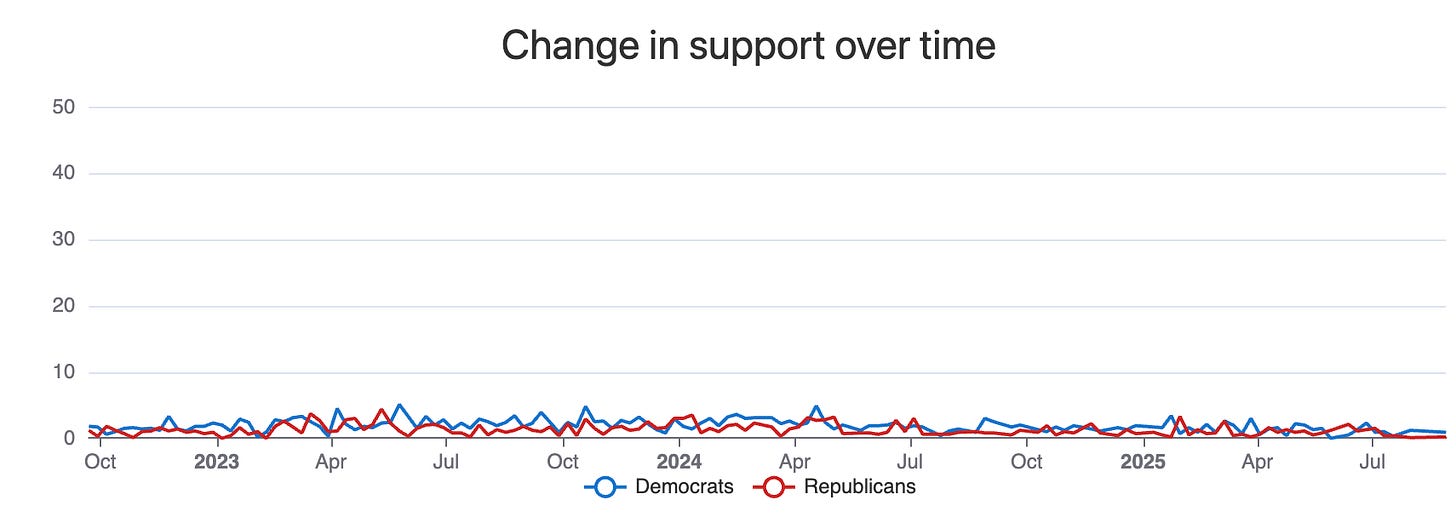

Westwood’s data is valuable because he has been collecting it for more than three years now, asking Americans the same questions week after week, in order to put together a reliable metric of how support for political violence has changed over time, not just where it stands in a single moment.

It is also helpful because, unlike other surveys, it doesn’t just ask about support for political violence broadly, which can lead to misleading responses. It asks about violence in searingly specific terms: it is one thing, after all, to vaguely tell a pollster you think “violence” might be necessary. It is quite another to explicitly say you support someone’s murder — and since acts of violence can only be carried out in specific ways (you can’t just “violence” someone), this is probably a more accurate gauge of how many people endorse actual violent acts.

Here is the question Westwood has been asking for three years:

[Name] was convicted of murder. He was arrested by police after surveillance footage was found showing him stabbing a prominent member of the other party to death. [Name] targeted the victim because he believed the victim had prevented him from voting in the last election as part of a conspiracy to stop voters from your party. Do you support or oppose [Name]’s actions?

On average, he has found, Democrats think 33% of Republicans will cheer on the action. Republicans think 34.3% of Democrats will express support.

But the actual numbers? In the lab’s most recent survey, conducted after Kirk’s assassination, only 0.9% of Americans expressed support for this act of partisan murder: 0.8% of Democrats, 0.8% of Republicans, and 0.9% of Independents.

Support had been slightly higher (around 3%) before Kirk’s murder — which shows, reassuringly, political violence only decreases support for political violence — but it has never wavered in all the time Westwood has been asking the question. Political murder is not popular.

We support free speech.

The other thing we learned after Charlie Kirk was killed was that government crackdowns on speech are not popular in America.

In one YouGov poll, 80% of Americans said the Trump administration should not be “using Charlie Kirk’s death as a way to silence political opponents,” including 88% of Democrats, 81% of Independents, and 72% of Republicans.

Only 7% said it should.

When YouGov made the question more specific, it did move the numbers — but, still, a supermajority of Americans said they oppose government actions to “pressure broadcasters to remove shows that include speech it disagrees with.” 68% of Americans said such actions would be “unacceptable”; only 13% said otherwise.

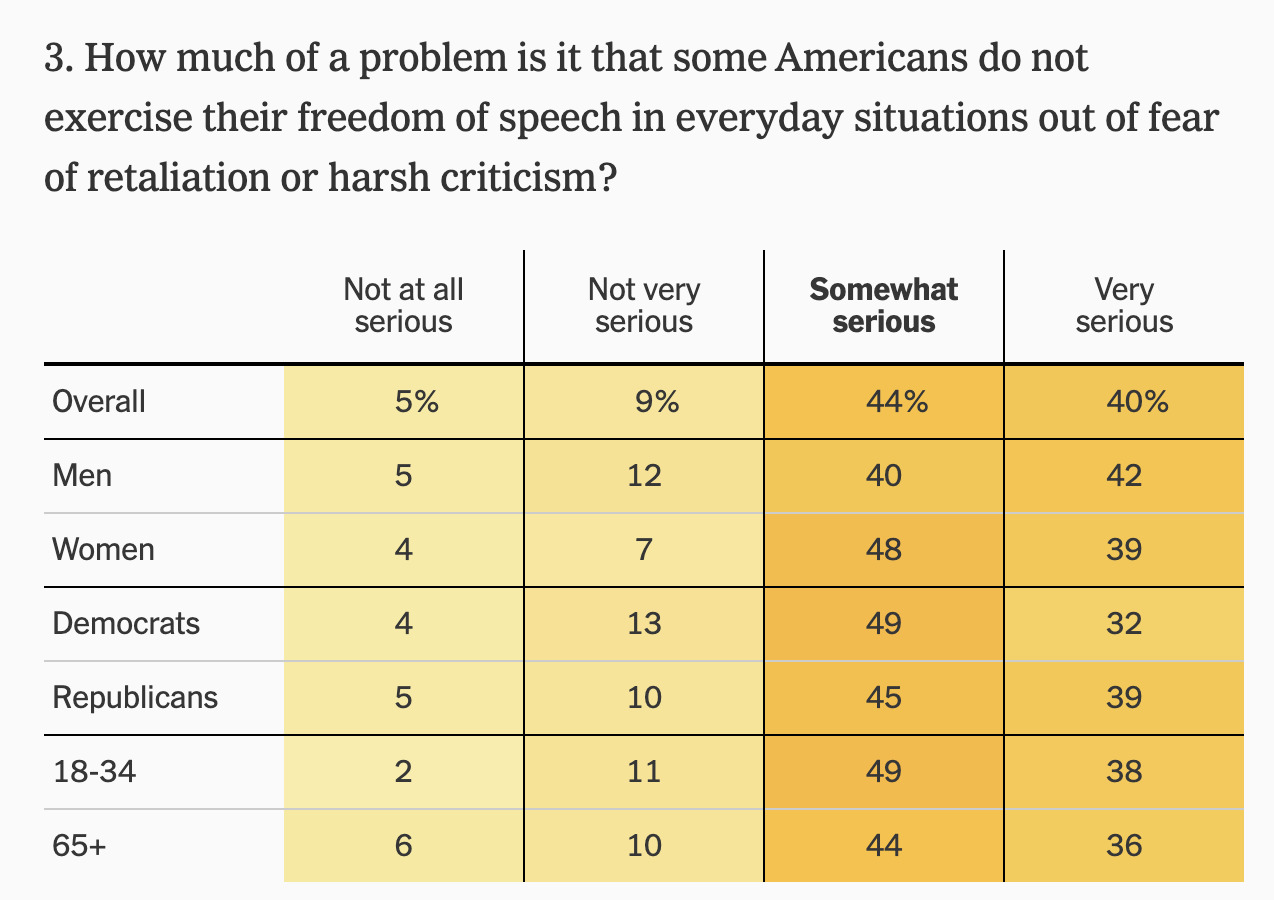

This shouldn’t be terribly surprising, since free speech was also popular during the era when it was progressives who were more vocal about trying to impose punishments for certain speech.

In a 2022 New York Times/Siena poll, 84% of Americans said it was a “somewhat” or “serious” problem that “some Americans do not exercise their freedom of speech in everyday situations out of fear of retaliation or harsh criticism.”

Right-wing forms of wokeness are proving no more popular than their predecessor. In addition to the GOP response to Carr, there was also the outcry after Attorney General Pam Bondi threatened to prosecute critics of Kirk as engaging in “hate speech,” a legal category that does not exist in the U.S. Bondi, too, backed down after criticism.

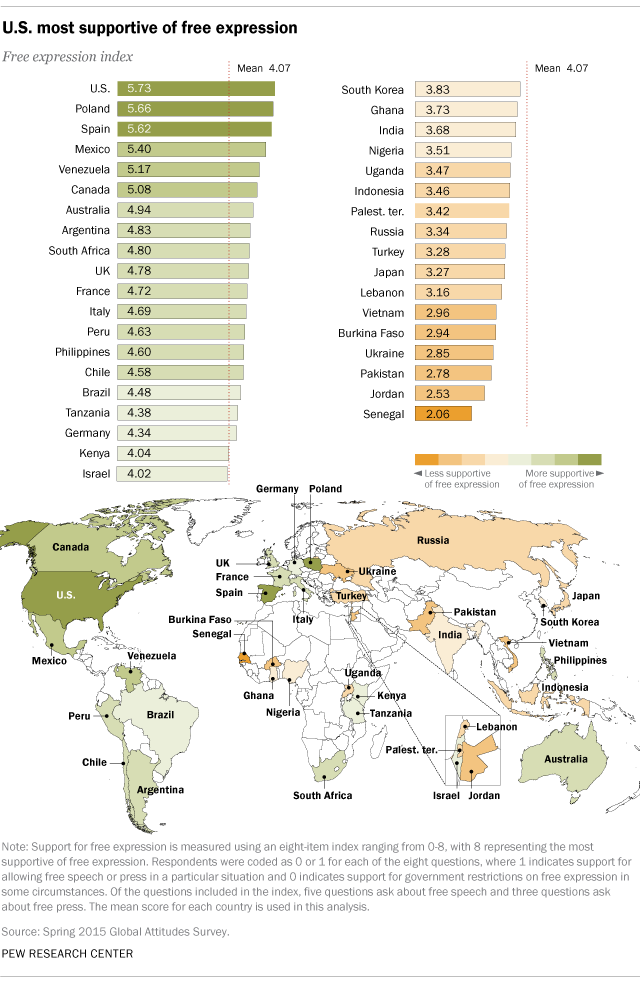

Polls within the last decade have shown that Americans are actually somewhat exceptional in our support for free speech. A 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center found that Americans rated higher than any other country on a “Free Expression Index” that incorporated responses to questions like whether others have the right to make statements that are offensive to minority groups (67% of Americans said “yes”) or to the respondent’s own religious beliefs (77% said “yes”).

Now, I understand that this might not sound all that notable. Americans support the 1st Amendment and the 6th Commandment: big whoop. That should be the bare minimum, right?

But I do think these findings are noteworthy in light of the hordes of people who are telling us the opposite, or whose fringe comments are being promoted to make it seem like the opposite, to give the appearance of violent and censorious majorities that do not exist.

In addition, as G. Elliott Morris recently noted in another piece demonstrating widespread opposition to political violence, “it is important to correct the record here” because “misperceptions about support for violence could actually raise support for violence,” creating a doom loop in which people think the other party supports violence so much that they must support it, too, which — at its most terrifying extension — could create a spiral of violent acts all because of a misperception.

It is healthy for a country to know the truth about itself, and here polling data suggests that Americans oppose political violence and support free speech. And supermajorities of Americans at that: these are literally 99-1 and 80-7 issues.

These are incredibly important values that we cannot structure a free society without — and we should appreciate the fact that, despite suggestions to the contrary, they both may have been threatened, but neither has been lost.

These are also connected concepts: support for free speech begets opposition to political violence, and vice versa. One cannot support political-based violence without opposing the idea that people should be able to speak their minds freely, and support for free expression requires an aversion to speech being met with violence.

Thankfully, in America, voters are not budging on either principle. Charlie Kirk’s murder was awful, and it unleashed all sorts of concerning responses, both in fringe expressions of support for violence and for more prominent expressions of support for censorship. But, really, the shooting and its aftermath showed us that we are more united on these ideas than we might think. I think that’s worth taking a moment to appreciate.

In other news…

The Supreme Court appeared to be leaning towards striking down a Colorado ban on conversion therapy during oral arguments yesterday.

Airports across the country are continuing to see delays — including a brief ground stop in Nashville — amid a shortage of air traffic controllers potentially connected to the government shutdown, one of the most visceral ways Americans are starting to feel the impact of the funding gap.

Attorney General Pam Bondi attacked several Democratic senators in personal terms during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, while Republicans probed into the revelation that former Special Counsel Jack Smith obtained the phone records of nine GOP lawmakers while investigating January 6th.

A bipartisan group of senators met over Thai food last night, a potential sign that cross-party shutdown negotiations are starting to take place.

Earlier this week, President Trump briefly seemed open to a health care/shutdown deal before backing away a few hours later. In yesterday’s newsletter, I offered a guess that Republican congressional leaders had spoken to Trump between the two statements, steering him back onto the party’s message. Later in the day, House Speaker Mike Johnson confirmed my prediction. As I wrote last month: “The most influential person in Washington is whoever Trump spoke to last.”

Taking advantage of a rules change recently implemented by Republicans that allows for approval of an unlimited number of nominees at once, the Senate confirmed Herschel Walker as the U.S. ambassador to the Bahamas and a scientist linked to “Sharpiegate” as the head of NOAA, along with 105 other Trump picks.

Happening today (all times Eastern): Former FBI Director James Comey will make his first court appearance since being indicted (10am) … President Trump will attend a “roundtable on Antifa” (3pm) … The Senate will vote for the sixth time on the Democratic and Republican government funding proposals (11:20am).

To express yourself is an open invitation to others to respond with their expression of speech. That is called discussion, debate, and communication. Freedom of Speech is a transaction between people.

How you speak, with anger or calmly, respectfully or hatefully, sets the tone of the conversation. The first speaker has the first responsibility to set the tone. The responding speaker also has the responsibility to respond respectfully and calmly, whether or not the first speaker is calm or respectful. But an ugly tone of communication is mainly the responsibility of the first speaker.

Freedom of Speech comes with the Duty to Respect.

I'll venture to say that this piece on political violence and free speech is some of the most important writing you've ever published, Gabe. Powerful in its own right, given the content, this entry also perfectly encapsulates your fact-based, hyper-rational approach to politics and the American experiment, which gives me hope. Kudos!