Trump’s GOP Makeover is Almost Complete

Republican Trump critics are Washington’s most endangered species. They’ll soon be even rarer.

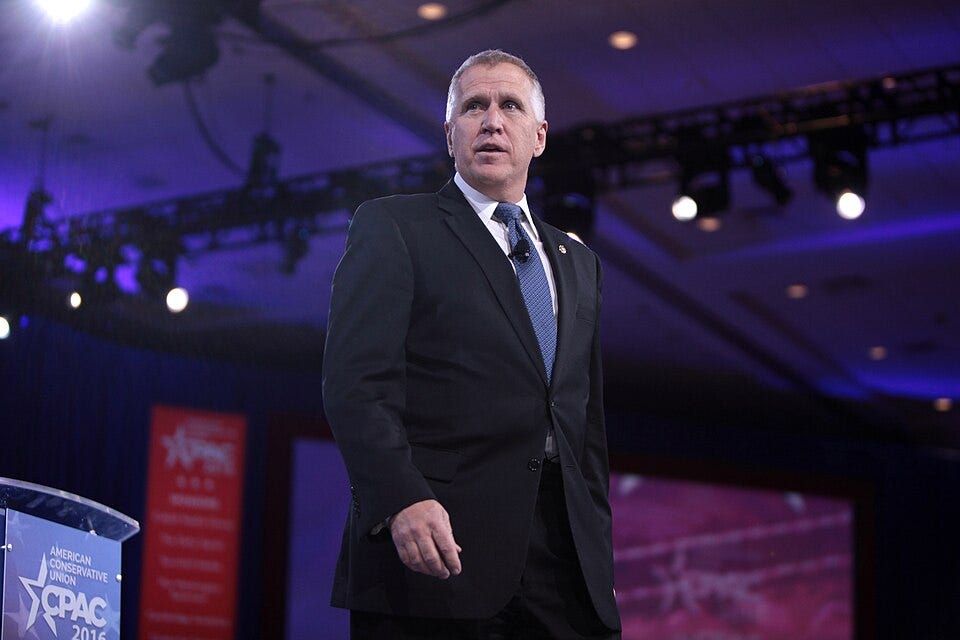

Thom Tillis seems to have had it.

The North Carolina Republican has never been the Senate’s most consistent Trump ally, but it’s almost like a switch has flipped for him in 2026. He started the year on January 6 with a stemwinder on the Senate floor, criticizing Trump for pardoning “criminals who injured police officers, who destroyed this building” five years earlier.

The next day, he continued with another impassioned floor speech, this one bashing what he called the “amateurish behavior” of Trump aides threatening to invade Greenland.

“Some people around here call me cranky,” Tillis acknowledged. “I have got a couple of buddies that call me cranky. Do you know what makes me cranky? Stupid. What makes me cranky is when people don’t do their homework. What makes me cranky is when we tarnish the extraordinary execution of a mission of fully supporting Venezuela by turning around and making insane comments about how it is our right to have territory owned by the kingdom of Denmark.”

In the subsequent weeks, Tillis has called for Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem to be fired, said that Trump aide Stephen Miller “never fails to live up to my expectations of incompetence,” compared them both to fictional villains, and vowed to block Trump’s nominee to replace Fed chair Jerome Powell until a criminal probe into Powell is dropped.

“I am sick of stupid,” Tillis said on the Senate floor last month.

With Tillis seemingly unleashed, it sure should make for some interesting confrontations with Trump over the final three years of the president’s term.

Oh, wait: Tillis has already said he won’t be seeking re-election this fall. He’s not alone, either. Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE), another frequent Trump critic, is retiring this year. So is Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who voted against more of Trump’s Cabinet picks this term (three of them) than any other Senate Republican. And former Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) has already resigned, after voting to block Trump from sending troops to Venezuela and signing the Epstein Files discharge petition in her final months.

The 2026 midterms could bring other casualties for the small faction of congressional Republicans who sometimes break with Trump. Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) is the most vulnerable Senate Republican on the ballot, and Trump doesn’t seem in a rush to save her. He recently threw his might behind a primary challenge against Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-LA), one of the seven Senate Republicans who voted to convict Trump in his second impeachment trial. (Of that group, if Collins and Cassidy lose re-election this year, only Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski will be left.) Trump has also blessed a primary challenger to Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY), the rare GOP lawmaker who reliably votes against the president’s top priorities.

“[Massie’s challenger] is running because he realizes Thomas Massie has been totally disloyal to the President of the United States, and the Republican Party,” Trump wrote on Truth Social this week. “He never votes for us, he always goes with the Democrats. Thomas Massie is a Complete and Total Disaster, we must make sure he loses, BIG!”

Pennsylvania Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick — one of two House Republicans, with Massie, to oppose the One Big Beautiful Bill, and the key Republican to sign onto a discharge petition forcing a vote on Obamacare subsidies — is poised to face a competitive re-election contest in November. So is California Rep. David Valadao (R-CA), one of the two House Republicans still in Congress out of the ten who voted to impeach Trump in 2021. The other, Washington’s Dan Newhouse, is retiring.

If you thought the current iteration of the congressional GOP was hesitant to split with Trump: just wait until you see next year’s. The already-tiny caucus of Trump-critical Republicans is about to be shrunken to a nub.

Now, if you’re feeling like you’ve read this story before, I won’t blame you.

It seems like every election cycle since Trump’s first term, there have been reports about the stream of Trump-averse Republicans leaving Capitol Hill (and, each time, not without reason). For example, here’s the Associated Press in the 2020 cycle:

Or the New York Times in 2022:

With Tillis, Bacon, and others now headed for the exits, it seemed possible to me that — after years of rumors — the near-extinction-level event for this small faction of the GOP might finally be arriving this year.

But instead of just writing another trend story, I wanted to test that intuition in a rigorous, empirical way. So, I ran the numbers.

For this analysis, I scoured congressional voting data to try to find the universe of Republicans who have shown a willingness to break with Trump in his two terms. I put together all the Republicans who voted against him on any of the following:

Either of his two impeachment votes/trials.

His signature tax cut bill from the first term.

His attempted Obamacare repeal from the first term.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act from this term.

His proposed rescissions packages in both terms.

Ending national emergencies or undoing tariffs he declared in either term.

Curbing his war powers in either term.

Voting against any of his Cabinet, Cabinet-level, or Supreme Court nominees.

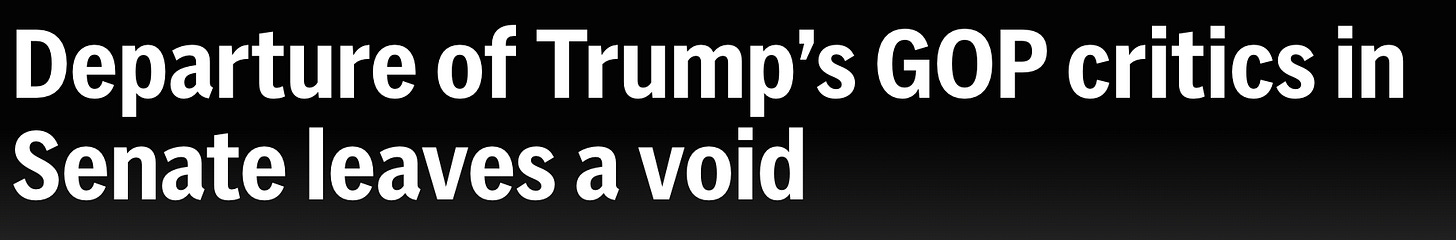

In total, that gives you 94 Republican lawmakers out of the 493 Republicans who have served in Congress since Trump’s 2017 inauguration. (The full list of 94 is here.)

Where are these 94 lawmakers now? Mostly not in Washington.

By the time Trump returned to the White House for a second term, 27 had retired. 16 had lost their seats. Three had died in office. Eight had resigned.

That left 40, fewer than half of the original group. But that’s not all.

Two more have resigned since Trump returned to office. 10 more are retiring this year. And six face potential defeat: Massie and Cassidy in primary challenges; and Collins, Fitzpatrick, Valadao, and California Rep. Darrell Issa, who opposed Trump’s 2017 tax bill, in general elections.

By this time next year, the group could shrink to as few as 22 Republicans in Congress who have ever broken with Trump on major votes. As many as three-fourths of Trump’s GOP critics will have left Washington over the course of a decade.

And yet, even that understates it a bit.

You see, the group of 94 includes everyone from Collins, who has broken with Trump on seven out of the eight categories analyzed, to some more surprising names like Marco Rubio, who voted to end Trump’s border emergency in his first term before becoming a key member of his Cabinet this term. (The past is a foreign country.)

What happens when we limit our universe only to Republicans who have broken with Trump on at least two of the categories — showing a repeated willingness to break with their party and the president, not just a one-off split?

That shrinks our group of Trump dissenters to just 31 Republicans, only 15 of whom were still in Congress by January 2025. Next year, with members of the group like Bacon, McConnell, and Tillis on the outs (and others like Massie and Collins on the bubble), this small club could shrink to six — and even this number includes lawmakers like Sens. Mike Lee and Jerry Moran, and Rep. Chris Smith, whose only breaks with Trump came during his first term and who have marched lockstep with the president since then.

In a year, it is possible that there will only be three Republicans left in Congress who have broken with Trump on more than one key front, including at least one break from his current term.

They are: Sens. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska (who has broken with Trump on six out of eight categories) and Rand Paul of Kentucky (four breaks), plus Rep. Mike Turner of Ohio (two breaks).

If Cassidy, Massie, Collins, or Fitzpatrick survive the midterms, the group will be a little larger — but in either event, the data tells the story: after a decade-long erosion, Washington will almost be completely devoid by 2027 of Republicans who have shown a consistent willingness to buck Donald Trump in Congress.

How meaningful is this?

If Republicans keep the House in November, it will certainly be significant. No more Massies and Bacons would mean a much more united coalition approving Trump’s policy priorities. It would likely mean no more discharge petitions wresting control of the floor from Speaker Mike Johnson, since many of the Republicans who have been willing to sign those petitions are headed for the exits.

If Republicans lose the House, as is expected, the impact will be different. Sure, there will be fewer Trump dissenters in Congress — but there won’t be much to dissent from anyway, at least in roll call votes, since Trump’s legislative agenda will be all but dead with Democrats in control of the lower chamber.

In that scenario, one lingering impact will be on my industry, the media. There’s nothing the mainstream media loves more than Republicans who break from the party line, and there’s a long history of these politicians commanding outsized coverage, from the OG “maverick” John McCain to Obama-era figures like Chris Christie and Jon Huntsman.

These days, it’s hard to open up a newspaper without running into a quote from Thom Tillis or Don Bacon bashing President Trump. Although their criticisms hardly register as a surprise anymore, their party labels give them credibility and provide oxygen for media stories about Republicans breaking with Trump. They are the only reason Politico is able to run a headline like this, since Tillis and Bacon were the main Republicans quoted:

Or why Reuters can call a bill pushing back on Trump’s coffee tariffs “bipartisan.” (Bacon was the only Republican co-sponsor.)

With these eminently quotable Republicans retiring, you can kiss goodbye to many of the stories about “Republican lawmakers criticizing Trump on X” or “bipartisan lawmakers sign on to Y bill.” In some ways, that might not feel notable — but, psychologically, it’s relevant.

Without many of the Republicans willing to oppose Trump in more than just a one-off way, Trump’s dominance over the party will look (and be) all that much more complete. Even if the current headlines mask the fact that only a few Republicans are quoted in those stories, without them, there will be little in the air questioning Trump’s grip on the GOP. Intraparty dissent will become almost nonexistent, minus stray comments from Rand Paul and Lisa Murkowski.

And less dissent will beget less dissent: quotes from members like Tillis and Bacon sometimes provide a permission structure, or a prod, for other Republicans to hesitantly creep out of the woodworks against Trump. There won’t be any more air cover coming from the gentlemen from North Carolina and Nebraska this time next year.

The other big impact, of course, is for what comes after Trump. The 94 willing-to-break-with-Trump Republicans cover a lost generation of GOP lawmakers, from senators like McCain and (soon) McConnell to others like Jeff Flake, Richard Burr, and Ben Sasse, as well as departed House members like Justin Amash, Liz Cheney, and Will Hurd.

For the next three years, the absence of the departing Trump critics will mean that, to the degree Trump faces resistance within his party, it will largely be coming from his right: yesterday’s government funding vote, when a group of MAGA-aligned House members flirted with a shutdown, provided a preview. The fact that any splits with Trump will come from MAGA members (since they are largely all that’s left) means the party will only push itself farther and farther to the right, with its ranks of moderates so thoroughly thinned.

And then, after Trump leaves the stage, it will mean that he will have almost fully remade the Republican conferences in Congress over his tenure: few pre-Trump Republicans are set to remain by 2029. Whoever takes over the party after Trump won’t have McCains or Bacons to reckon with: they will be leading a transformed party — which isn’t to say, of course, that it won’t transform itself again in unpredictable ways. (Parties tend to do that.) But any sort of return to Romney or Nikki Haley-style Republicanism is, at this stage, impossible to imagine, partially because its adherents on Capitol Hill (once numerous) have almost all gone extinct, replaced with MAGA successors.

In some ways, this is due to Trump’s influence, but not exclusively. 16 of the 94 Republicans are gone because they lost re-election bids — but only four of those were due to primary challenges. 12 lost in general elections, continuing a trend that has gripped our politics in recent decades: moderate members willing to break with their party line tend to come from the most competitive seats (due to the ideological composition of their districts), but that means that they are also the opposition party’s first targets in an election year.

Over time, this means that each party has snuffed out some of their most willing partners from the other side of the aisle, leaving both parties mainly consisting of their most rabidly ideological core, talking themselves into moving farther right or left because the mushy middle has been hunted for sport. That can lead parties to predictably unhealthy places, once almost all of the willing dissenters have been washed out, and only loyal partisans are left. Nobody remains to question party excesses, leading to a party that might be smaller but is also more unified, and thus willing to overreach even more (often to its own detriment).

For Trump, that could mean feeling even less hemmed in by Republican criticisms during his final two years in office — an eventuality he seems already to be planning for.

Asked recently about Tillis’ threats to block his Fed nominee, Trump said, “Well, you know, that kind of thinking is why he’s no longer a senator.”

“I mean, you know, if he doesn’t approve,” Trump added, “we’ll just have to wait ‘till somebody comes in that will approve it, right?”

Not sure I understand this essay without a reference to gerrymandering. The use of this SCOTUS sanctioned device to create politically safe Congressional races invites extremists from both parties, and I include in that term MAGA members. Crowding out candidates who understand that politics is the art of compromise has harmed Congress immeasurably, resulting in once impossibly extreme right wing initiatives, such as the advancement of the powers of the president. It is gerrymandering that undermines democracy (and causes other kinds of harm). Trump has exploited that at the state level, using his enormous Federal powers to compel Greg Abbott and other Governors to redistrict mid-term. If the Congressional districts were more competitive, it might reduce the MAGA threat.

Well, this is depressing. I've been hoping that Republicans would just implode from overwhelming meanness. Guess that was a pipe dream.