The Supreme Court Is The Median Voter

Or at least it was this year.

The most elusive figure in American politics is the median voter.

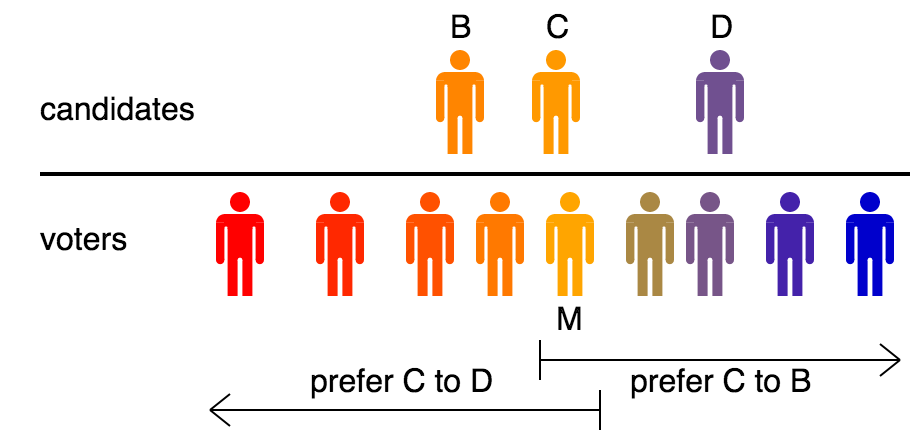

In political science, the term comes to us from the Scottish economist Duncan Black, who proposed the “Median Voter Theorem” in the 1940s. His theory was that, if candidates and voters were aligned on an ideological spectrum, an election will always be won by the candidate whose positions are closest to those of the electorate’s median voter, since that’s the candidate who will be most broadly acceptable to the most voters.

Median Voter Theorem isn’t always true — there’s a whole range of things it doesn’t account for, including the fact that voters’ perceptions of a candidate’s positions won’t necessarily align with the candidate’s actual positions — but it can still be a helpful concept.

At any rate, on the internet, the idea has taken on a life of its own, as confirmed by the Know Your Meme official meme database. On social media, users will sometimes poke fun at the fact that the median American voter is hard to pin down, with an ideologically heterodox mix of policy views.

After all, the median voter has cast ballots for George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump. They don’t neatly align with either party’s platform. They want to build a border wall, and also provide a path to citizenship for immigrants here illegally. They support protections against discrimination for transgender people, and also believe transgender athletes should compete on the teams that match their sex at birth. The median voter supports voter ID laws, and sending absentee ballot applications to every voter. They believe that it’s the government’s responsibility to ensure all Americans have health care, and also oppose a government-run health care system.

The median voter is confusing.

Or, at least, they are to anyone whose political engagement is mostly through the lens of following national politics, where very few participants would explicitly express support for those position pairings, for fear of upsetting an interest group in their coalition.

But, at long last, a group of scholars from Harvard, Stanford, and the University of Texas may just have found the fabled median voter — and apparently there’s nine of them, they wear black robes, and they all went to fancy law schools.

Professors Maya Sen, Neil Malhotra, and Stephen Jessee have been tracking opinions about Supreme Court opinions since 2020, conducting polls to find out how often the justices are producing outcomes that a majority of Americans want.

This term, they stumbled on a first: The court aligned with public opinion in every single major ruling.

This means that, just like the median voter, the justices sometimes lunged left and sometimes lunged right.

Allowing parents to opt their children out of lessons on gender and sexuality at school? The Supreme Court said “yes,” just like 77% of the public.

Making it easier to sue police officers for excessive force? Again, the court said “yes,” just like 66% of Americans.

Should states be allowed to ban transgender minors from obtaining certain treatments? 64% say they should, and so does the court.

Should the federal government be allowed to regulate “ghost guns,” firearms made by homemade kits? 75% of respondents — and a seven-justice majority — say they should.

In practically every case, the court aligned not just with a majority but a supermajority: with the 64% of Americans who don’t think U.S. gunmakers should be financially responsible for crimes committed by Mexican cartels, the 65% of Americans who support the FDA’s ability to ban flavored vapes, the 70% of Americans who believe that someone claiming reverse discrimination should have to meet the same standard as minorities claiming discrimination, and the 80% who back age verification for pornographic websites.

The court even tied on the exact issue that was most divisive among the public: Americans were split 51% to 49% on whether public charter schools should be allowed to be religious, with the slimmest of majorities saying “no.” As if they were reading the poll, the Supreme Court split 4-4, due to a recusal from Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who had ties to the religious charter school in question. (Even here, the effect of the court’s opinion aligned with the public majority, since their tied decision kept in place a lower court ruling blocking the school.)

The next closest issue was on whether the government should be able to ban TikTok, although the court agreed with a 58% majority that it should.

The pollsters did not ask about one of the court’s liberal-leaning opinions from the term, upholding the legality of a task force that recommends which types of preventive care that insurance companies have to cover, or the court’s Trump-friendly opinion blocking nationwide injunctions. (The pollsters instead asked about birthright citizenship, the issue at the heart of that case — but which the justices didn’t rule on — which 58% of voters support.) Other polls, however, suggest, that both decisions boast majority support.

In all, the term’s rulings represent a remarkable alignment with public opinion, even on controversial issues like guns and LGBT rights that are at the center of America’s culture wars.

In an interview, Malhotra — a Stanford political economist who is one of the academics behind the Supreme Court Public Opinion Project — told me that the court’s alignment with the public is part of a recent trend that they’ve picked up on.

In the 2021 and 2022 terms, which included controversial decisions like Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the court ruled to the right of the public on several key cases, Malhotra said. But, in the terms since Dobbs, the court had moderated, more consistently ruling in accordance with public opinion. This was the first time it was a perfect match.

Looking back on the past several Supreme Court terms, Malhotra summarized: “One thing we know is they’re never more liberal than the public,” but they aren’t “consistently always more conservative,” either.

“So they’re either kind of where independent voters are, kind of the median voter, or they’re kind of where the average Republican voter is,” Malhotra said. “But it fluctuates.”

If you take the past decade into consideration, it does sort of seem like a Republican-Leaning Independent Court, maybe a Susan Collins Court: anti-transgender discrimination, pro-banning gender affirming surgeries, pro-Obamacare, pro-life, pro-abortion pill, anti-affirmative action, with more right-leaning positions on guns and the environment thrown into the mix. It’s approximately the issue profile of an Obama-Trump voter.

Of course, the justices aren’t supposed to rule based on their political preferences, or the preferences of the public. While the poll asks voters what their preferred outcomes of various cases would be, the justices are supposed to follow the law wherever it leads, no matter what outcome that produces.

“Lawyers really hate this poll,” Malhotra told me. “They don’t like the idea of comparing the public’s view on the policy implications to the decisions, which are supposedly based on jurisprudence.”

But previous scholars have suggested that the Supreme Court does, indeed, try to follow public opinion, although views on this are mixed.

Malhotra suggested a middle ground: perhaps the justices — who, unique among federal judges, have near-complete control over their docket — are honestly deciding the cases they hear based on the law, but they are choosing to hear those cases with some attention to public opinion, only taking up the cases where they know they won’t be veering too far from the country at large.

“My instinct is both that there are strategic litigants and that there’s a strategic court, that is kind of framing the issues and giving cert to issues which are popular,” Malhotra said. (When the justices agree to hear a case, it is known as “granting certiorari,” or “cert” for short.)

Based on his research data, that the court has moved more to the center since 2022, Malhotra speculated that the justices have particularly been trying to do this post-Dobbs, in order to reclaim a moderate image and their legitimacy in the eyes of voters who have lost faith in the court. (If that’s their goal, it isn’t working: views of the Supreme Court have sunk to a record low, even as the justices increasingly issue rulings that the public would agree with.)

Other scholars have argued that the Supreme Court often aligns with public opinion not due to strategic efforts by the justices, but because “the justices’ preferences shift in response to the same social forces that shape the opinions of the general public.” It’s not that the justices are especially attuned to the national mood, in this view; they are just a good barometer of it (and sometimes, as with approving same-sex marriage, they help shape it in turn).

This could, perhaps, help explain a court that backed transgender rights in 2020, when wokeness reigned supreme, but declined to do so in 2025, during a conservative vibe shift.

“I think we understate how much general social vibes influence court decisionmaking,” Malhotra said. “Obviously they’re also trying to make legal precedents and follow laws and have legal reasoning. But, because they don’t have any real power, they kind of have to string this line where they can’t be seen as too out of step with the public.”

If that’s the goal, at least for this term, they strung that line unbelievably well, planting themselves firmly with the supermajority position on case after case after case.

Is there a median position on abortion? It seems that on this issue the majority of the Supremes, three nominated by Trump in term one, are badly out of step with public opinion. That court's Dodds decision, striking down Roe v Wade, made the reproductive rights of women a matter of a lottery, depending on the state she lives in.

This “theory” is disingenuous. This analysis ignores all of their recent shadow docket rulings that give the [current] GOP president the powers of a king, while taking power from themselves AND the legislative branch to do so. Most of the public disagrees with Trump on almost every major issue now, and his numbers keep falling and will only continue to do so. What about abortion? I know it was decided in a previous term, but it’s relevant in that it was a MAJOR unpopular decision that not only overturned a SCOTUS precedent to get a result they wanted, but it cited pre-enlightenment, magical thoughts from several centuries ago to do so (see Alito).

The theory that majority SCOTUS is making decisions to coincide with public opinion doesn’t square with SCOTUS’ historically low current approval rating, and I also find it dangerous. The relatively ‘safe’ consensus issues cited here as proof that SCOTUS appeals to the average “median voter” only gives SCOTUS legitimacy as they upend the separation of powers, as laid out in our Constitution, while they simultaneously make a mockery of our rule of law as they hand more wealth to oligarchs and more power and hierarchical status to [white male] “Christian” nationalists, and I guarantee you that the average “median voter” does not agree with these efforts.