The Republican Defendant Protection Program

A deep dive into Trump’s pardons.

At first blush, there isn’t much that separates Robert Henry Harshbarger from any other white-collar ex-convict.

He’s a former pharmacist who was charged with health care fraud in 2012, ultimately pleading guilty to distributing a drug for kidney dialysis patients that he claimed was an FDA-approved medication but was, in fact, a cheaper substitute from China.

According to prosecutors, over the course of five years, Harshbarger’s company received more than $875,000 from a dialysis center and more than $845,000 from programs like Medicare and Medicaid in exchange for the misrepresented drugs.

“Although there are no reports of patient harm associated with the drugs that are alleged to be misbranded in this indictment, patient health was put at risk,” the U.S. attorney said at the time. “The FDA cannot assure the safety and effectiveness of products that are not FDA-approved and come from unknown sources and foreign locations or that may not have been manufactured under proper conditions. These unknowns put patients’ health at risk because of uncertainty concerning the product’s content, purity, and source.”

Harshbarger was sentenced to two years in federal prison, which he served.

When Ted Kennedy first ran for the Senate in 1962 — at age 30, never having held elected office, seeking the seat that his brother had just vacated to become president — his rival in the Democratic primary famously said from the debate stage: “If his name was Edward Moore…your candidacy would be a joke. But nobody’s laughing, because his name is not Edward Moore. It’s Edward Moore Kennedy.”

Similarly, if our ex-con here was named Robert Henry, this is probably where his story would end. But his name is Robert Henry Harshbarger, and his wife is Diana Harshbarger, a Republican congresswoman from Tennessee and a top Trump ally. Last week, Mr. Harshbarger was quietly pardoned by the president, wiping his criminal record clean.

Harshbarger joins a group of roughly 1,500 people whom Trump has pardoned since returning to office about 10 months ago.

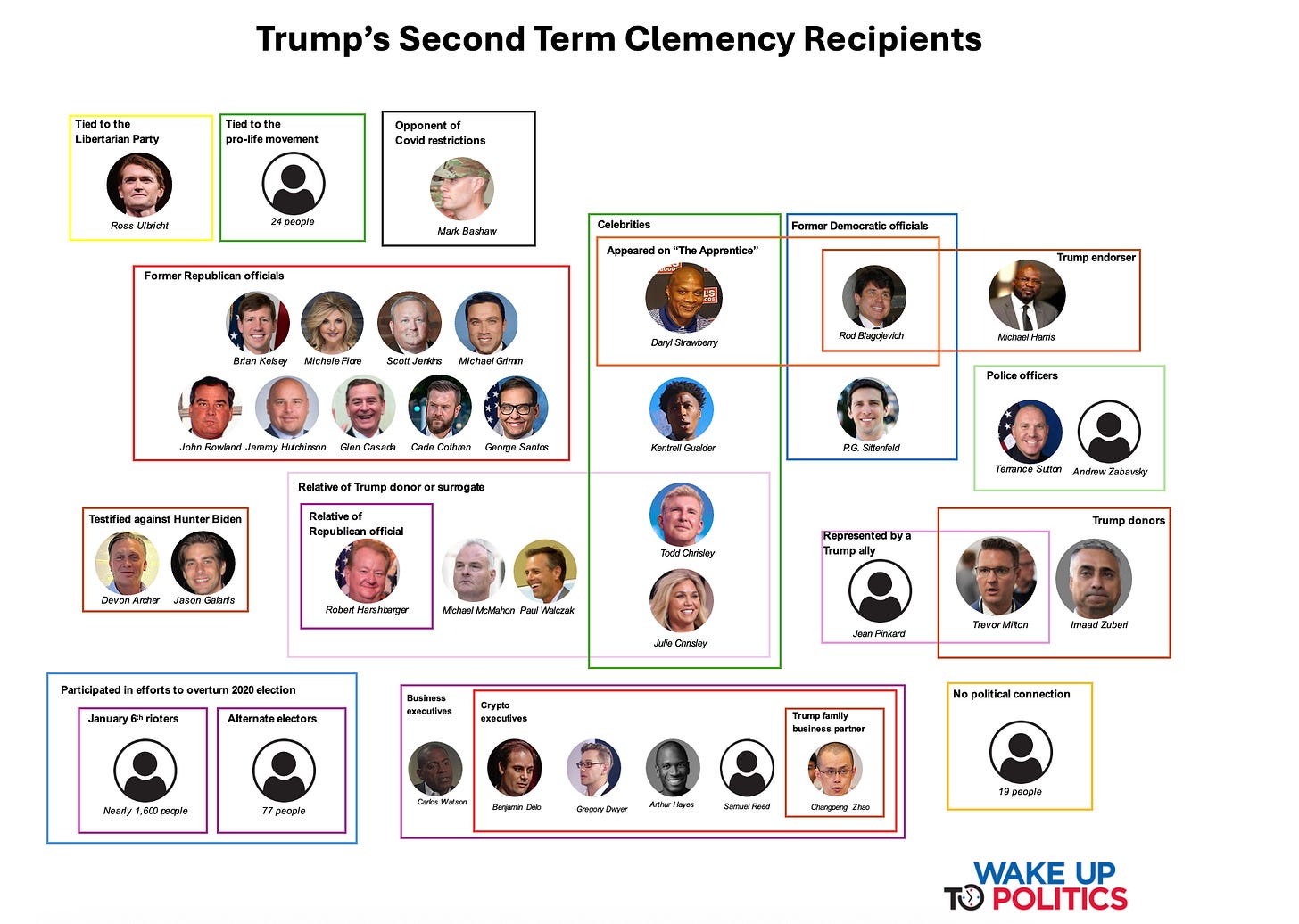

The list is largely made up of January 6th rioters, but it also includes a trail runner, two shark divers, five crypto executives, an alleged Chinese agent, and the operator of an online black market known as a haven for illegal drug trafficking.

And a lot of Republicans.

Throughout his second term, Trump has used his clemency powers to aid Republican politicians battling criminal charges at all levels, from former city council members and county sheriffs to former state representatives and senators.

With his pardons or commutations of former Reps. George Santos (R-NY) and Michael Grimm (R-NY) this term — and former Reps. Chris Collins (R-NY), Duncan Hunter (R-CA), Steve Stockman (R-TX), Rick Renzi (R-AZ), Mark Siljander (R-MI), Robin Hayes (R-NC), and Duke Cunningham (R-CA) last term — Trump has granted clemency to almost every Republican House member to have been federally convicted of a felony this century.

Nine days after returning to office, Trump’s Justice Department also moved to end the case against another convicted former congressman, ex-Rep. Jeff Fortenberry (R-NE), despite the fact that Fortenberry had already been convicted for lying to the FBI about a foreign campaign contribution. Two days after that, federal prosecutors withdrew from the criminal investigation of Rep. Andy Ogles (R-TN), a top Trump ally who was being probed for potential fraud.

There hardly seems to be a Republican lawmaker in legal trouble, even stretching back to the early aughts, whose case Trump has not intervened in — always on the side of the Republican defendant. The courtesy apparently extends also to Republican congressional spouses, as the Harshbarger pardon shows.

Many of Trump’s other second-term clemency recipients are tied to him or his orbit: Trevor Milton, who was convicted of defrauding investors in his company Nikola, was pardoned after donating almost $1 million to the Trump campaign or political groups backing Trump. Paul Walczak, convicted of tax crimes, was pardoned one month after his mother attended a $1 million-per-seat Trump fundraiser. Changpeng Zhao was pardoned after the crypto exchange he founded, Binance, struck a deal with the Trump family company.

Other pardons have been to benefit individuals in Trump’s broader ideological coalition, like an Army officer who disobeyed Covid safety measures, two D.C. police officers convicted of murder and a subsequent cover-up, and 24 pro-life activists convicted of forcibly entering and blocking access to abortion clinics. Devon Archer and Jason Galanis were convicted of defrauding a Native American tribe and pension fund investors out of tens of millions of dollars, but were pardoned after they testified in the House Republican investigation of Hunter Biden. (Both were former associates of the ex-First Son.)

Still more acts of clemency have seemed to contradict Trump’s policy priorities, like his support for law enforcement (see: pardons for the January 6th rioters who attacked police officers), his concern for waste, fraud, and abuse in health care programs (see: Harshbarger, who defrauded Medicare and Medicaid), and his anti-China rhetoric (see: his pardon for a retired cop who was convicted for stalking a New Jersey family on behalf of the Chinese government, but whose wife is a vocal Trump supporter).

Clemency is one of the broadest authorities granted in the Constitution — there are no limits to who the president can pardon — and Trump is far from the first to use the power to benefit allies. Bill Clinton pardoned Marc Rich, a donor to his library and his wife’s Senate campaign, the former Democratic congressman Dan Rostenkowski, his half-brother Roger Clinton and others in his last day in office. George W. Bush commuted the sentence of Scooter Libby, his vice president’s former chief of staff. (Trump later granted Libby a full pardon in his first term.) Joe Biden pardoned his son Hunter on his way out the door.

But Trump’s pardons stand distinct for the sheer number of political allies he has helped, and for the fact that he has appeared to completely shed the traditional pardon process — which requires a formal application and months of vetting — and instead seems to be offering pardons based purely on access. (An entire cottage industry of lobbyists has reportedly emerged around reaching Trump on pardons.) Pardon recipients are also traditionally mandated to still pay any court-ordered restitution to their victims, a requirement that Trump has dropped; according to an analysis by House Democrats, this has wiped away about $1.3 billion that his clemency recipients had been ordered to pay employees, investors, taxpayers, and other victims.

As ever, Trump is also more brazen than most about the political nature of his pardons. During his 2024 campaign, he appeared at the Libertarian National Convention and promised to grant clemency to Ross Ulbricht, the online black-market founder, in a bid to win over the third party’s voters. He made good on his pledge one day after returning to office; the next day is when he pardoned the pro-life activists, an act timed for the March for Life that was taking place simultaneously.

When announcing that he’d commuted Santos’ sentence, Trump explicitly invoked the ex-congressman’s political affiliation: “at least Santos had the Courage, Conviction, and Intelligence to ALWAYS VOTE REPUBLICAN,” Trump wrote. The pardon recipient whose mother was a top Trump donor openly included her active support for the president on his pardon application. After the president pardoned a pro-Trump former sheriff convicted of bribery, Ed Martin — who has orchestrated many of these clemency grants as the president’s pardon attorney — wrote on X: “No MAGA left behind.”

Many of Trump’s clemency grants have also been issued quietly; while previous presidents posted public White House press releases disclosing their pardons, Trump’s are often only added to a list on the Justice Department’s website — sometimes days after the fact. This is how the Harshbarger pardon became public; a list of 77 preemptive pardons for allies involved in the 2020 fake electors scheme was posted by Martin on X earlier this week, but still does not appear on the DOJ list. Nor does a pardon for an Idaho trail runner who announced his own pardon on social media on Monday.

In addition to the many pardons for Republican officeholders, Trump has also granted two pardons this year to politicians who held office as a Democrat. One is Rod Blagojevich, the former Illinois governor who was convicted for trying to sell a U.S. Senate seat, whose sentence Trump had previously commuted in his first term. The other is PG Sittenfeld, the former Cincinnati city council member convicted of bribery and attempted extortion (and the brother of novelist Curtis Sittenfeld, author of books like “Romantic Comedy” and “Rodham”).

Blagojevich was a former contestant on “The Celebrity Apprentice” who supported Trump’s 2020 and 2024 campaigns and has declared himself a “Trumpocrat.” Trump has no known connections to Sittenfeld, whose pardon Vice President JD Vance has pointed to in order to argue that Trump’s pardons are apolitical.

“This is not about politics. This is about the law,” Vance said. “And if the president thinks a person has been unfairly prosecuted, he’ll pardon that person or commute their sentence. If he thinks a person has violated the law, whether they’re a Republican or a Democrat, he’s going to encourage his Department of Justice to go after that person.”

However, the number of pardons Trump has granted Republican politicians far outstrips those given to Democrats — especially if you discount “Trumpocrats.” And, at the same time, while pardoning his allies, Trump has carried out prosecutions of his foes, including former FBI Director James Comey, former national security adviser John Bolton, and New York attorney general Letitia James.

“For my friends, everything. For my enemies, the law,” the Peruvian president Óscar Benavides is claimed to have said in the 20th century. Trump railed against a “two-tiered system of justice” during his 2024 campaign, but he seems to be living by Benavides’ philosophy now.

> “For my friends, everything. For my enemies, the law,” the Peruvian president Óscar Benavides is claimed to have said in the 20th century

I found it attributed to a Paraguayan dictator, with comment that it is attributed to many other people, too. Sounds like something you'd expect to come from Rome, though.

it’s official. We are a banana republic.