The Ghosts of Trump’s Early Presidency

The moment that I think best represents his second term.

In the fast-moving Trump era — where every week brings a fresh news cycle and things can change on a dime Truth Social post — looking back at coverage from only a few months ago can already feel like excavating ancient history.

Remember DOGE, which was once the dominant project of Trump’s second term, but is now barely referred to? (The agency has reportedly shuttered, eight months before it was supposed to. Meanwhile, Elon Musk and Donald Trump seem to have somewhat repaired their feud — another saga you forgot about. Musk did recently say, though, that if he could go back in time, he wouldn’t have joined the administration.) Or the president’s never-enacted goal of buying Greenland?

It’s interesting, sometimes, to wander back into these headlines and try to place yourself into the national mood as they were going on. During the early weeks of Trump’s second term, the widespread feeling was very much that he was all-powerful, a vibe he cultivated and that many on the left and right bought into. Republicans gloated about a permanent lease on the White House they had gained, thanks to young and Hispanic voters who had moved into their coalition. Democrats fretted about a constitutional crisis on the horizon. Members of Congress were largely silent.

Trump’s most muscular use of power during this period was probably his deportation, in March, of around 250 migrants to the infamous prison in El Salvador known as CECOT. No action better represents Trump’s second term than this one, an audacious flex of power that was ultimately revealed to rest on a precarious foundation of legality, forcing its undoing.

There were several layers at play here: Trump gave many of the migrants almost no due process, which several judges quickly rejected. He tried deporting some under the Alien Enemies Act, a 1798 wartime law which courts later ruled that he was missaplying. And the planes that ferried the migrants to El Salvador kept flying despite a verbal order by U.S. District Judge James Boasberg, telling them to turn around.

The planes continued on, though, and for a time, it seemed like the migrants existed in a liminal space, beyond the reach of U.S. law. Ross Douthat, the conservative New York Times columnist, openly wondered whether Trump had located Gödel’s Loophole, the defect that logician Kurt Gödel had supposedly found in the Constitution that would allow a president to become a dictator. Could a president theoretically deport any of his political enemies, and then disclaim any responsibility to get them back, since they were no longer on U.S. territory?

As this was going on, the migrants at CECOT were experiencing absolutely brutal treatment — beatings, having their hands stomped on, dirty water being poured on their ears, experiencing sexual assault and a lack of medical care — at the hands of Salvadoran guards who were effectively acting as subcontractors for the U.S. government.

Trump shrugged it all off. “He who saves his Country does not violate any Law,” the president wrote on social media not long before this saga, almost threatening the courts to stop him.

But then, the courts did stop him. In the long run, Trump’s attempt to deport migrants in the U.S. to a Salvadoran “hell on earth” failed.

The highest-profile migrant Trump sent to CECOT was Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who the U.S. eventually recognized had been mistakenly deported to El Salvador. White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said that Abrego Garcia would “never live in the United States of America again,” but the Salvadoran native was brought back to the U.S. in June — after the Trump administration spent two months dragging its feet in complying with a Supreme Court order to return him.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said she hoped the rest of the migrants at CECOT would stay there “for the rest of their lives” — “You’ll leave here dead,” they were reportedly told upon their arrival — but the remainder of the American-sent migrants have also been released, as part of a July prisoner swap that ended the U.S. attempt to house migrants at CECOT, after the effort kept running into legal obstacles.

The story isn’t over yet, though: The long tail of this Trump attempted power play, stretching back to the early weeks of his second term, has reared its head in two ways recently.

First, Kilmar Abrego Garcia was released on Thursday from an immigration facility in Pennsylvania, where he had been most recently detained after being returned to the U.S. (He is also awaiting trial for criminal charges in Tennessee.) U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis ordered his release in a ruling that detailed the “extraordinary” history of Abrego Garcia’s case, and accused the Trump administration of lying to the court about its plans for Abrego Garcia. “The administration did not just stonewall,” she wrote. “They affirmatively misled the tribunal.”

Xinis found that at no point since Abrego Garcia’s encounters with immigration officials began in 2019 had an immigration judge issued a final removal order mandating his deportation, which meant the administration could not continue holding him in detention.

Second, Judge Boasberg attempted to revive proceedings to potentially hold the Trump administration in contempt of court for flouting his verbal order directing the planes to El Salvador to turn around.

Boasberg was planning to hold hearings today and tomorrow with former and current Justice Department attorneys to investigate the administration’s decision to move forward with the planes. “This inquiry is not some academic exercise,” Boasberg wrote in an order rejecting the administration’s request to postpone the hearings. “Approximately 137 men were spirited out of this country without a hearing and placed in a high-security prison in El Salvador, where many suffered abuse and possible torture, despite this court’s order that they should not be disembarked.”

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit then issued a ruling Friday night blocking the hearings from taking place.

Neither of these stories is at its end. The Justice Department will likely appeal Abrego Garcia’s release. And the panel ruling in the Boasberg inquiry will likely be appealed to the full D.C. Circuit, just as the full court previously allowed the inquiry to continue after a three-judge panel paused it the first time — though that process took seven months.

I wanted to write about all this today because I think it’s worth dwelling on how the long tails of certain actions can live on to haunt an administration for months, and how not everything plays out how it seems in the moment.

Whether or not Abrego Garcia returns to detention, or Boasberg’s contempt inquiry continues, the fact that the Trump administration has long since given up on housing migrants at CECOT — figuring it was more trouble than it was worth — bears out the lesson that what seems like a power flex at one time can look different after several months, once it runs into political and legal realities.

Trump is learning this a lot lately, in ways that make his presidency come off a lot differently than it did in the days when he was sending migrants to El Salvador.

In recent weeks, with his second term about to turn one year old, he has suffered rejections at the hands of GOP state legislators (in Indiana) and the Republican-controlled Congress (with the Epstein Files). Senate Republicans continue to defy him daily on blue slips and the filibuster. As with the CECOT deportations, his attempts to run roughshod over U.S. courts with attempts to prosecute political rivals are running into roadblocks, including court rulings blocking his U.S. attorney appointments and grand juries foiling his plans.

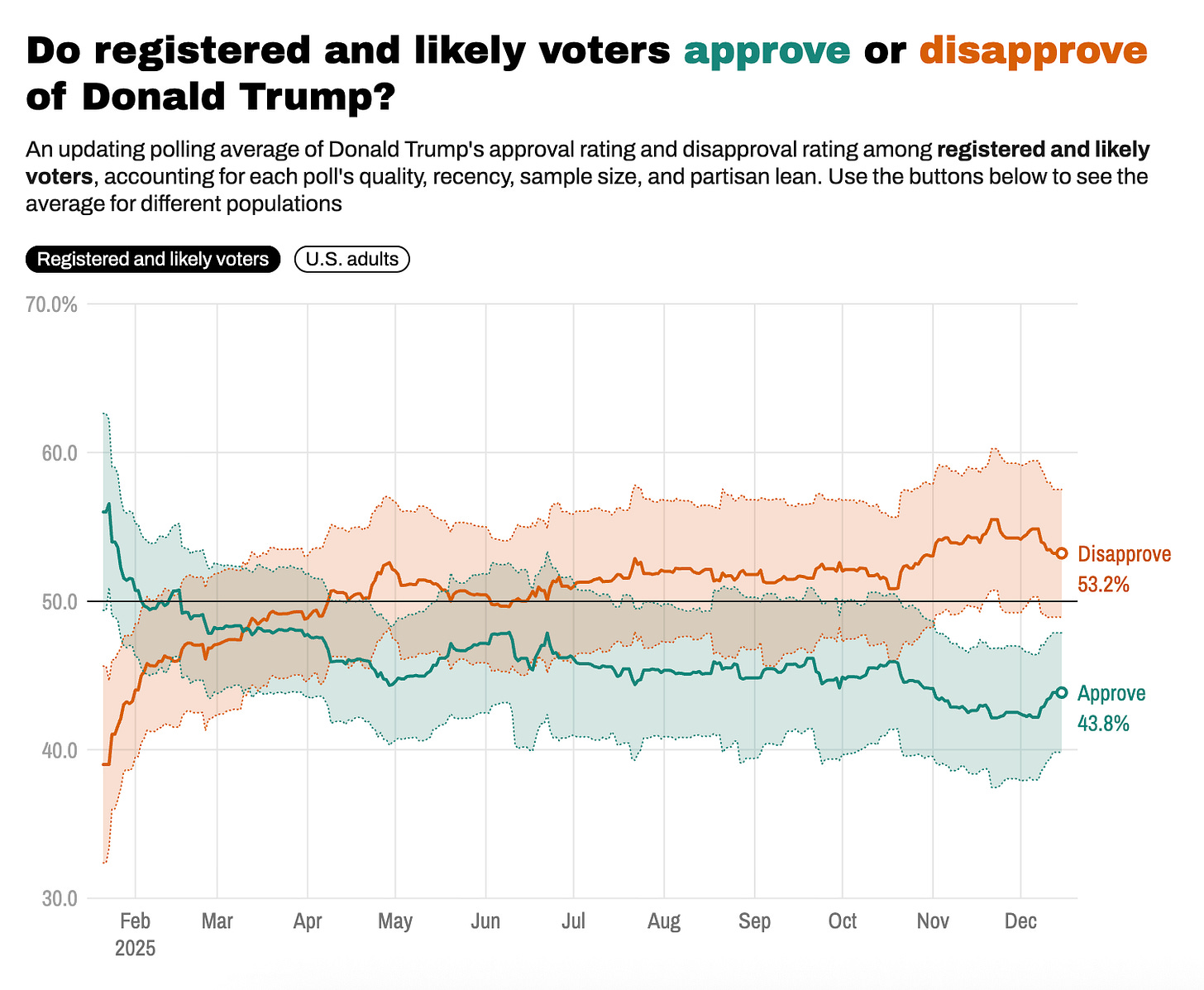

Trump is also markedly less popular than he was when the CECOT story began. It was right around this all happened, in March, that his approval rating slipped under 50% for the first time since returning to office; it has never recovered.

The CECOT deportations are a perfect symbol of this trajectory: a presidency that once seemed unconstrained by law or politics, but quickly overshot its runway and drained ints political and legal goodwill. There is maybe no more audacious thing Trump has tried to do this year — sending 250 people to one of the world’s most brutal prison, without any clear legal license allowing him to do so — and yet, it turned out to be a failure and a legal mess that haunts the administration to this day.

Even as losses mount in courts and special elections, Trump continues to ignore these lessons. The most obvious example is how he continues to dismiss the concerns about inflation that are battering his political fortunes.

Another example, in a very different domain, from this morning — Trump’s post about the death of Rob Reiner:

The last time Trump tried to use a tragedy as a way to divide, instead of unite, Americans, it backfired: Senate Republicans emerged in droves to oppose his efforts to police speech in light of Charle Kirk’s assassination. Not that it will receive the same visibility, but I would not be surprised if Trump’s almost boasting response to Reiner’s death similarly marks a step too far for many Republican lawmakers and voters.

Trump will likely spend the rest of his second term trying to recapture the feeling of his first few months, when he appeared on top of the world and Democratic and Republican dissenters were afraid to suggest otherwise. But you don’t get that deference when you’re unpopular, and little of what Trump is doing lately suggests he understands that connection, or is trying particularly hard to regain his bygone popularity. Without it, he’s unlikely to regain that power.

DOGE may be gone, but it's not a victory. As someone directly effected by their threats, the deferred resignation program (DRP), and looming RIF's and reorganizations, they won. We lost about a third to DRP- and I don't blame people for leaving! But that work still needs done, so who do you think has to double up? No hiring is happening- not that I really want anyone who could get hired right now to work with me with all the loyalty stuff they're putting into it.

Even though my department was fully funded after a month and a half long shutdown, we're not getting funds like normal- instead they are doling it out monthly. Like children, federal departments are having to save up their allowance to make large purchases that are necessary. Add on to that- the purchase cards of many are still set to $1. We went from 20 cardholders to 1. Now a scientist is making purchases for all of us and doing nothing else. Oh- and they can't properly spend because their monthly limit didn't budge.

DOGE did it's damage and disappeared because it's job was done. We're thoroughly terrorized, exhausted and demoralized. The public may not yet feel the full effect of DOGE, but they will. And I have so little hope of restoration to what we once were. Who would want to come work here now?

Gabe , this was another excellent column. In particular, I value the long view analysis into the underpinnings of what happened during the first year of Trump's term that are beginning to catch up to him. Not many people can navigate through the trees to uncover the forest as well as you just did. Thank you for your thoughtful commentary.