The curse of the incumbents continues

Upheaval is coming for the global West.

It’s always hard to know how future scholars will regard the present day, but it seems increasingly likely that the Biden presidency will go down in history mostly as a blip, a brief aberration cushioned between two Trump terms.

Peering around the global stage, it looks like he might have company.

In September 2021, nine months after Biden entered office, federal elections in Germany and Canada elevated center-left leaders in Olaf Scholz and Justin Trudeau. The next year, France re-elected its center-right president, Emmanuel Macron. Later, in 2024, Keir Starmer ended Conservative Party rule in the United Kingdom, giving the country a center-left prime minister.

Like any collection of contemporaneous world leaders, this group of five — arguably the most powerful figures in the global West — features important differences. They span the age spectrum, from 46-year-old Macron to 82-year-old Biden. Macron and Trudeau are more flashy; the rest are more bureaucratic. They each hail from varying domestic contexts, and their ideologies are far from monolithic. Some of them don’t even get along personally.

And yet, there are also glaring commonalities. They’re all white men. They’ve all spent lifetimes in or around government, entering politics or advocacy in their 20s or 30s. Broadly speaking, they’re all institutionalists and internationalists: supportive of Ukraine and sympathetic — at least compared to their domestic rivals — to alliances like NATO and the European Union. They all occupy roughly the political center in their countries.

The picture of four-fifths of them below (Trudeau is missing) could easily be the stock photo on a corporate website; if you didn’t know any better, you might think they were friendly partners at the same law firm. Indeed, several of them began their careers as attorneys.

They have one more thing in common: their time in power could soon be coming to an end.

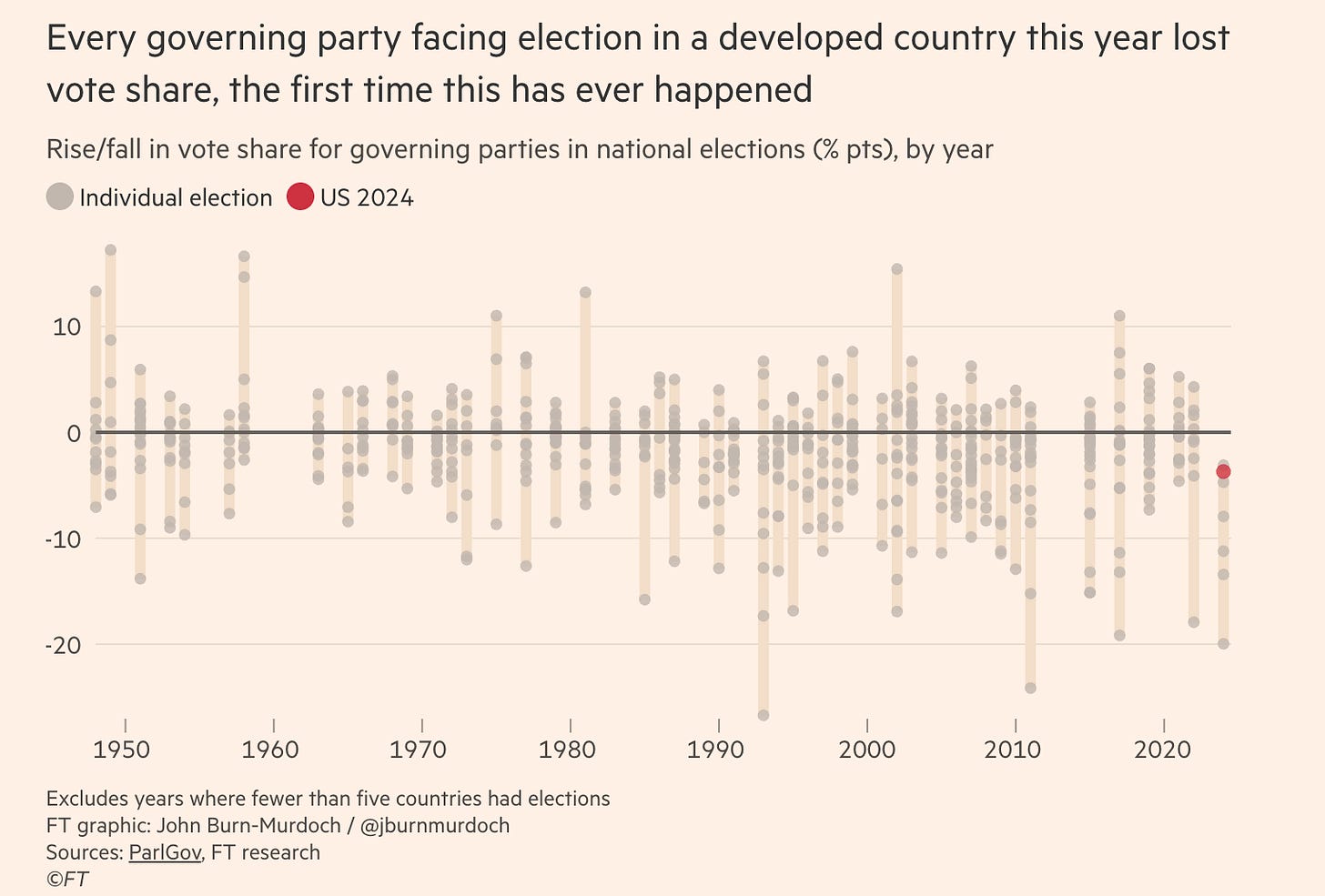

I know, I know: it’s not exactly news that incumbents are faltering across the globe. If 2024 was the “Year of Elections,” then the verdict is clear: governing parties were the losers. Per the Financial Times, incumbent parties lost ground in every election in a developed country this year — the first time that’s happened in 120 years of records.

But 2024 isn’t done with these beleaguered incumbents just yet. The final month of the year has brought yet another dose of bad news for all five leaders:

Biden is exiting office as something of a political pariah; after his vice president’s defeat, whatever personal regard (or mid-campaign unity) that had kept Democrats from criticizing him seems to have broken, with his fellow party members apparently calculating that they gain more from bashing than defending him at this point. Look no further than the response he received to his Hunter Biden pardon and several of his of commutations. If even like-minded moderate Amy Klobuchar is distancing herself from Biden, then you know he has a problem.

Scholz’s government collapsed on Monday after a vote of no-confidence by the German parliament. As a result, new elections will be held in February; polls show the chancellor’s center-left Social Democratic Party trailing the center-right Christian Democratic Union.

Macron is in a similar boat, after the French legislature ousted his prime minister last week in the country’s first successful no-confidence vote since 1962. Macron is now on his fourth PM of the year; he says he will remain in office, but calls to resign are already mounting.

Trudeau is also facing pressure to step down from his own party members — and reportedly he’s considering it. His finance minister resigned on Monday with a scathing letter, citing disagreements on how to respond to Trump’s threatened tariffs. Elections are set to take place in October at the latest; polls uniformly show the Conservative Party trouncing Trudeau’s Liberals.

Starmer is the newest member of the group — he only took office in July — but already faces trouble as well. Polls show dissatisfaction with the premier soaring; now, a petition calling for fresh elections has notched two million signatures. Starmer says he won’t call new elections, although (like any other formal petition that notches more than 100,000 signatures) it will receive a debate in parliament next month.

What can we make of this month of upheaval? (And this is even putting aside the regime change in Syria and impeachment in South Korea.)

Again, the exact circumstances differ by country, but certain patterns are evident. After a populist surge in the late 2010s, the period during and just after Covid was thought to have triggered a collapse in support for populist parties. Amid the chaos of the pandemic, voters either elected or re-elected more mainstream figures, seeking steady leadership in a time of crisis.

One columnist called it the “revenge of the centrist dads.” Two political scientists — borrowing from the world of finance — said the trend represented a “flight to safety.” (Starmer, elected the farthest from the pandemic, is the exception that proves the rule: his 2024 victory may have come later than the rest, but it marked a break with the UK’s chaotic string of Covid-era leaders.)

But all five flights ended up hitting turbulence.

Some of those were for idiosyncratic reasons; others were very much shared: the wars in Ukraine and Gaza; a wave of immigration; the post-Covid economic hangover that has hit each country.

Centrist-led coalitions, often appealing in a time of crisis, are often difficult to maintain long-term: just as Biden’s political brand ended up falling victim to frustrations from the left and right, Trudeau is caught between the left-wing New Democratic Party and the populist Pierre Poilievre to his right. Even with the right-wing AfD as a common enemy, Scholz’s “traffic-light coalition” with other left-of-center parties ended up being stretched too thin to hang on.

After last week’s vote of no-confidence, Macron blamed a “coalition of the irresponsible,” blasting the left-wing New Popular Front and right-wing National Rally parties for ganging up against him.

Biden, remarkably, will leave office as the most popular of this quintet: his otherwise unimpressive 37% approval rating, per Morning Consult, is still higher than Starmer’s 30%, Trudeau’s 26%, Scholz’s 19%, or Macron’s 18%. It’s hard to make friends from the middle.

These developments all accrue to Trump’s favor — and he’s gleefully responded to some of them. In a Truth Social post last night, Trump once again trolled Trudeau (the leader most his ideological opposite) by calling him the “Governor” of the “Great State of Canada” in a post responding to the Canadian finance minister’s resignation.

In January, Trump will re-join Italy’s Giorgia Meloni at the leading edge of global right-wing populism; next year’s elections in Canada and Germany (where AfD currently polls in second place) could elevate their ideological allies.

After their stock briefly rose mid-Covid, many of the “centrist dads” are coming back to earth; with their promised post-pandemic stability nowhere to be seen, many of their voters appear to be looking somewhere new.

Extremely well-written and thoughtful analysis.

Great article as always. Just to clarify though, Trudeau wasn’t elevated in 2021. He has been PM since 2015; his Liberal Party was reelected to a minority government in 2021.