The College Freshman Behind Alabama’s New Election Map

He drew the map at 3 a.m. in his college dorm room. Alabama will use it next November.

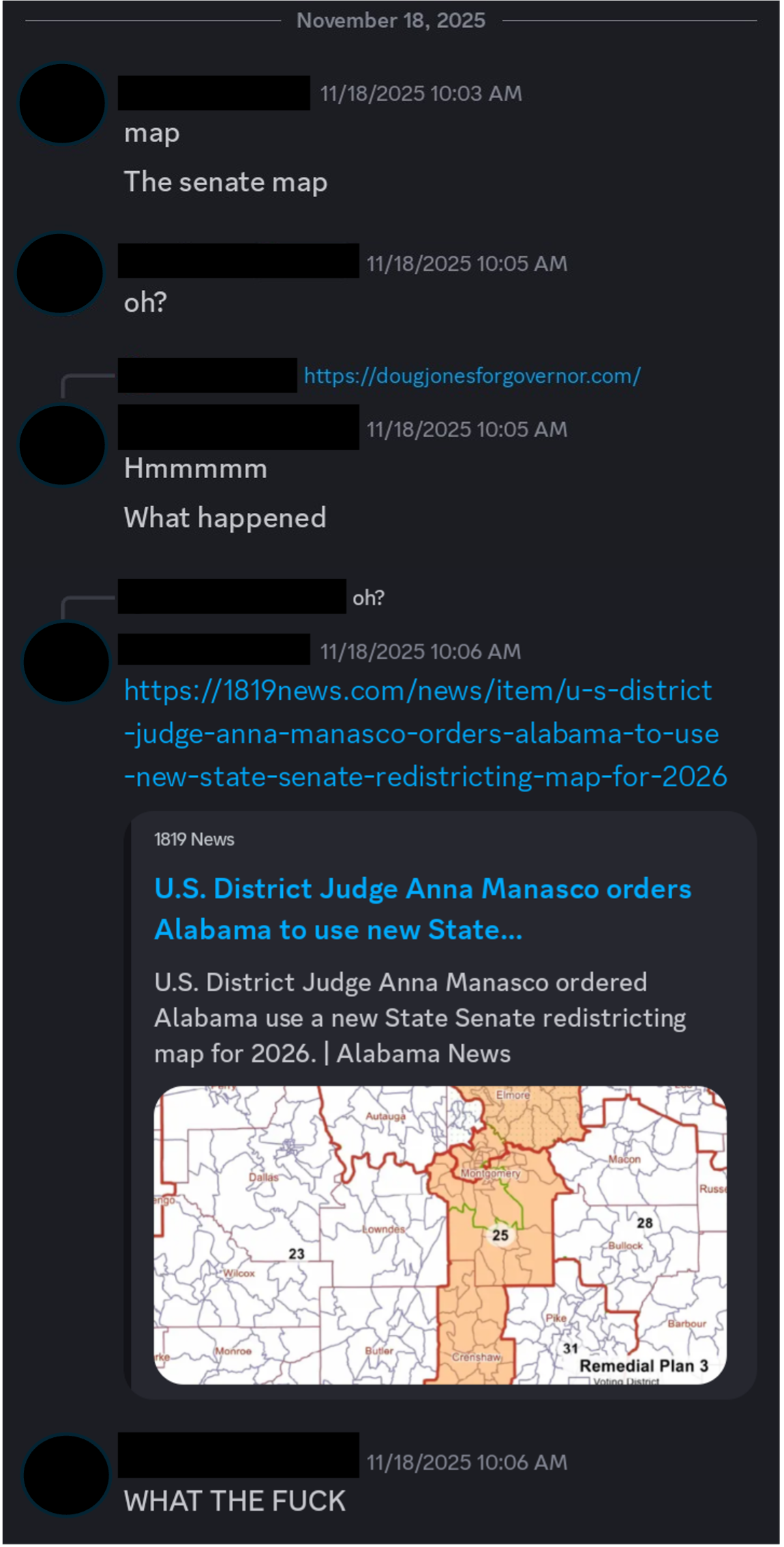

Daniel DiDonato had just woken up to leave for class at the University of Alabama, where he is a freshman, when he received a text from a friend on Discord.

“The map,” his friend texted him. “The senate map.”

“What happened,” DiDonato responded.

His friend sent a link. “WHAT THE FUCK,” DiDonato replied.

Most 18-year-olds wouldn’t have such a strong reaction to a judge picking new district lines for the Alabama state Senate — but then again, most 18-year-olds weren’t the one who drew the chosen map. “300,000 Alabamians will be voting under district lines that I drew myself in my college dorm room,” DiDonato told me in a recent interview. “And that’s just … wow.”

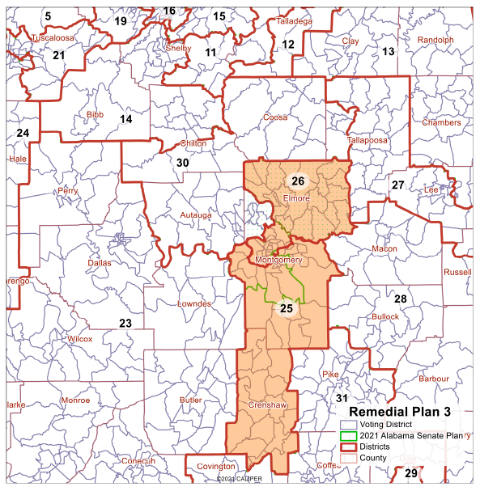

DiDonato had plunged into a legal process that dated back to 2021, when the Alabama state legislature released a new state Senate map following the previous year’s census. That map was quickly challenged by the NAACP, who claimed that it illegally packed most Black voters in the Montgomery area into a single district. The ensuing court battle inched along slowly; eventually, in August of this year, U.S. District Judge Anne Manasco sided with the challengers.

Manasco, a Trump appointee from his first term, tapped a special master (an independent, court-appointed attorney) on October 1 to propose a new map with an additional heavily-Black district in Montgomery, in order to undo the Voting Rights Act violation she found in the first map. On October 2, Special Master Richard Allen put out an order welcoming submissions from either party in the case or any “other interested person.”

It turned out that only one person was. In fact, DiDonato was one step ahead of the special master. Only a day elapsed between Allen’s appointment and his order, but in that time, DiDonato — a native of Seale, Alabama, who was closely following his state’s redistricting process — had already emailed the special master, asking whether it would be possible for him to submit a proposed map and have his name redacted because he was a minor. (DiDonato has since turned 18.) Allen said that was fine; although proposals were generally meant to be submitted over a court docket (which requires hiring an attorney), his team would set up an email address for anyone without a lawyer to submit a map themselves.

The highly specific requirements for map submissions would still stand: proposals had to be submitted in the “SSCCCTTTTTTBBBBDDDD” format, according to Allen’s order, “where ‘SS’ is the 2-digit state FIPS code; ‘CCC’ is the 3-digit county FIPS code; ‘TTTTTT’ is the 6-digit census tract code; ‘BBBB’ is the 4-digit census block code; and ‘DDDD’ is the district number, right-adjusted.” There probably aren’t many college freshmen in America who could understand that jargon, but DiDonato is one of them. He has been following politics since 2016, when he was in fourth grade, and enjoys looking at old election maps (and drawing new ones) in his spare time. So, he got to work.

DiDonato settled into a common-area study room in his University of Alabama dorm hall; over the course of several late-night sessions there and in his dorm room, sometimes stretching into 3 a.m., DiDonato used Dave’s Redistricting App (a free tool that allows anyone to redraw state legislative and congressional maps for every state) and carefully crafted six submissions for the court. Then, he waited.

On October 24, the special master released his report. He and his cartographer had received only nine submissions — three from the NAACP and six from DiDonato (identified as “D.D.”, with a notation that he was a minor) — and drawn two of their own. The special master forwarded three to the court: his two, and “Remedial Plan 3,” one of the submissions from “D.D.” DiDonato was excited, until he realized that his map was only included because the special master felt (as he wrote) that it “weakly remedies” the racial gerrymandering problem, and that its inclusion would make the special master’s own maps look better by comparison. “It was really disheartening,” DiDonato told me.

Judge Manasco disagreed. After holding a hearing to consider all three proposals (the court invited DiDonato to attend, but he couldn’t find transportation from Tuscaloosa to Montgomery), she ruled last month that the “D.D.” proposal was the best one. The map, with its then-unknown dorm-room origins, would now be the new state Senate map for Alabama. That’s when DiDonato received the text from his friend on Discord, with whom he often chats about politics.

Barely awake, DiDonato was about to leave for his “Intro to American Politics” class. (“I love the class, but I hate that it’s at 9:30,” he said.) “This is 9:05 in the morning. My brain hadn’t fully turned on yet.” But then his friend sent the news article announcing that “Remedial Plan 3” had been chosen. “I just, like, mentally lost it,” DiDonato said.

DiDonato’s map is not without its critics. In fact, Judge Manasco appears to be its only cheerleader. The special master likes his plans better. The state of Alabama has said DiDonato’s map is the “least bad” option, but views any new map as suspect, believing they will all have been illegally “drawn with a racial target.” (Dave’s Redistricting App allows users to choose which information they see as they craft their maps, and DiDonato says that the racial filter was toggled off while he was drawing. He also said he identifies as a Democrat, but approached the map without any partisan motivation in mind.)

On the other side, the NAACP says that the map doesn’t take race into account enough: “Black voters could only rarely elect Black candidates” in the new Montgomery district drawn by DiDonato, the NAACP has said, and will only be able to elect their preferred candidate if the candidate is white. (DiDonato says that is a misreading of the case law, which only requires that the district give weight to Black voters’ preferences, not to the race of the candidate they prefer. The judge agreed. In 17 elections analyzed by the court, the Black-preferred candidate would have won in the district DiDonato drew more often than not.)

Despite those hesitations on all sides, the fact that DiDonato’s map was chosen is no accident. He went into the process with a very specific strategy: “I knew the court would be limited in whatever plans it chose, such that the court doesn’t have much discretion to pick any redistricting plan,” he told me. “The court would have to pick a redistricting plan that hewed as closely as possible to the previously enacted redistricting plan.”

DiDonato knew that the most obvious way to draw another heavily-Black district in Montgomery — the route the special master and the NAACP would choose — would be to redraw three districts in the area. “My question I asked myself was, ‘Is it possible to draw a redistricting state Senate plan in which only two state Senate seats are reconfigured, in a way that provides an additional Black-opportunity seat?” DiDonato predicted that Judge Manasco would feel legally constrained to pick the plan that altered the existing map the least, while still giving Black voters in Montgomery the voting power she had ordered.

He was right. “Controlling Supreme Court precedent dictates rules that the Court must follow in ordering a remedial plan,” Manasco wrote in her eventual ruling. “The Court does not have the authority to simply select the plan that outperforms all other proposed plans on any particular metric and order the Secretary to use that plan. The Court must give the Alabama Legislature as much deference as possible, and the Court may not disturb the policy choices in the Enacted Plan any more than is necessary to remedy the likely [Voting Rights Act] violation this Court found.”

Therefore, because the “D.D.” plan altered only two districts — leaving 97.6% of the original map intact, more than any other submission — as long as it corrected the Voting Rights Act violation, Manasco decided that she had to choose it. “The Court must adopt Remedial Plan 3 [DiDonato’s plan] if it is a lawful remedial plan,” she wrote. “If Remedial Plan 3 is such a plan, the Court has no discretion to adopt a remedial plan [such as the NAACP or special master’s proposals] that modifies three districts in the Enacted Plan.”

DiDonato, a college freshman, had correctly anticipated what the NAACP and a court-appointed cartographer had not. “That was the angle I was looking to play this entire case,” he said. “If you can call it an angle.” The map he drew in his dorm room is now poised to be used for Alabama’s state legislative elections for the rest of the decade.

“The Voting Rights Act has existed since 1965. It was born in the civil rights era that Alabama has a very dark history of. Alabama has a very dark history of electoral racial discrimination and basically intentionally working to cancel out the power of minority voices,” DiDonato, who is Filipino-American, told me. “And I got to be a part of the story of fixing that. I got to be a part of the story of the struggle for minority voting power that’s existed in this state for literally 60 years now.”

Like many other redistricting battles this year, however, the story is not over. The NAACP, believing that DiDonato’s map does not do enough to remedy that discrimination, has appealed its selection. DiDonato told me that he would “love” to submit an amicus brief in the 11th Circuit, where the appeal will be heard, to defend his map, as long as he can “find an attorney who’s willing to represent me pro bono.” (Asked if he had looked for one, DiDonato said: “I know I need to get on that, but it’s just something I’ve been procrastinating.” He is a college student, after all.)

For now, though, he’s on winter break, unwinding after an undeniably successful semester for a political science major.

DiDonato wanted his name hidden originally, but once his map was chosen, he wasn’t averse to unmasking himself: he started emailing local Alabama reporters before even telling his parents that he had just redrawn their state. (“It’s not something they really understand, but they think it’s cool,” he said.) DiDonato told me that he hopes his story “inspires other young people to know their voice has power and that they too can be the change they want to see in society.”

And yes, he sent the emails from his Political Science 101 class, which he still attended that day.

Election mapping is “data science, but it’s also an art,” DiDonato told me. “It’s just something that’s really beautiful to me, and it’s something I love to study.” He often plays with Dave’s Redistricting App between classes. “Do you remember the Wisconsin state legislative redistricting case from a few years ago?” he asks me. He’s working on a map that could have been used in that case now.

“If there’s one good thing about the fact that we can surgically engineer optimized redistricting gerrymanders,” DiDonato said, “it’s that the technology is also there for people to just make their own maps. Anybody can be a part of the redistricting process. All it takes is a web connection.” (In this case, he acknowledged, “anyone was allowed to. I was just the only person who actually did so.”)

DiDonato said that he views his interest in mapping as a natural outgrowth of his longtime interest in elections, since he views redistricting as the most “consequential” part of the election process. “Nothing shapes elections quite like the lines under which the elections take place,” he said. “Those who control the maps control the election, put simply.”

How does it feel now that he’s the one with that control?

“It’s just so humbling, I’d say... It shows that really anybody can be a part of the political process. I saw an opportunity to make my voice heard and to make a difference for my state, and I took it. It’s just so mind-breaking to think about sometimes.”

"He has been following politics since 2016, when he was in fourth grade, and enjoys looking at old election maps (and drawing new ones) in his spare time."

Why am I not surprised that you two found each other? :-).

Thank you for showing us that the upcoming generations are up to the task of democracy.

Happy holidays.

Great story, Gabe. I'm not sure DD realizes that most of us wouldn't have the slightest idea how to use Dave's redistricting platform and wouldn't try, even though we now know it exists.